The human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals, commonly known as hunting, has shaped societies for millions of years. This deeply embedded activity spans various motivations, from the primal need for sustenance and essential animal products like fur, hide, bone, tusks, horn, and antler, to recreational pursuits and the contemporary demands of wildlife management. The very word “hunt” carries a rich history, serving as both a noun describing the act and a verb denoting the pursuit, a testament to its multifaceted role across human experience.

Tracing its linguistic roots, the noun “hunt” emerged in the early 12th century, derived from the verb “hunt.” Old English featured terms such as “hunting” and “huntoþ.” By the 1570s, its meaning expanded to encompass “a body of persons associated for the purpose of hunting with a pack of hounds.” Around 1600, it gained the more general sense of “the act of searching for someone or something,” echoing its broader application today in phrases like “treasure hunting” or “hunting for votes.”

The verb “hunt,” Old English “huntian,” meaning “to chase game,” likely developed from “hunta” for “hunter.” It is connected to “hentan,” meaning “to seize,” stemming from Proto-Germanic “huntojan,” which also gave rise to Gothic “hinþan” (“to seize, capture”) and Old High German “hunda” (“booty”). This etymological journey reveals a practice intrinsically linked to human efforts of acquisition and capture, a general sense of “search diligently” recorded as early as circa 1200.

Hunting manifests in diverse forms, each with distinct purposes and methodologies. Recreational hunting, also termed trophy hunting, sport hunting, or “sporting,” focuses on large mammals often referred to as big game, including the iconic Big Five game—lion, elephant, African buffalo, African leopard, and black rhinoceros—alongside bear, bison, boar, tiger, reindeer, caribou, and deer. Medium and small game hunting encompasses pursuits like fox, mink, coon, hare coursing, and squirrel hunting.

Avian species are targets of fowling, further categorized into waterfowl hunting, shorebird hunting (snipe, woodcock, curlew, sandpiper, plover), and upland hunting (quail, pheasant, grouse, turkey). Beyond recreation, hunting serves critical functions in pest control and nuisance management, including predator hunting of wolves, jackals, coyotes, and bobcats, as well as varminting against rabbits and rook shooting. Another significant category is culling, employed for population control.

Commercial hunting and traditional sustenance hunting historically provided essential resources, covering practices such as seal hunting, whaling, dolphin drives, dugong hunting, alligator hunting, and kangaroo hunting. Other specialized forms include falconry, green hunting (the pursuit of animals without intent to kill, like for photography, though still called hunting), and the illegal activity of poaching, which involves unauthorized and unregulated killing, trapping, or capture of animals. Trapping, a distinct method, is also recognized within the broader spectrum of hunting activities.

The history of hunting stretches back deep into the annals of human evolution, predating Homo sapiens and potentially even the genus Homo itself. Undisputed evidence of this practice dates to the Early Pleistocene, aligning with the emergence and early dispersal of Homo erectus approximately 1.7 million years ago, a period characterized by the Acheulean culture. While Homo erectus were undeniably hunters, the extent of hunting’s influence on their evolution, including the development of stone tools and control of fire, remains a subject of debate between the “hunting hypothesis” and theories emphasizing omnivory and social interaction.

Direct evidence of hunting prior to Homo erectus, for example in Homo habilis or Australopithecus, is not definitively established. Early hominid ancestors likely maintained a diet of frugivory or omnivory, with meat consumption primarily derived from scavenging rather than active hunting. Nevertheless, comparisons with chimpanzees, our closest extant relatives who engage in troop predation, suggest that occasional hunting behavior might have existed in the Chimpanzee-human last common ancestor as far back as 5 million years ago.

Some indirect evidence points to Oldowan era hunting by early Homo or late Australopithecus, supported by a 2009 study of an Oldowan site in southwestern Kenya. However, scholars like Louis Binford in 1986 critiqued the notion of early hominids as hunters, concluding from skeletal remains analysis that they were predominantly scavengers. Blumenschine in 1986 proposed “confrontational scavenging” as a leading method for early humans to obtain protein-rich meat, involving challenging and scaring off other predators after a kill.

The development of hunting tools progressed over millennia. Stone spearheads found in South Africa date back as far as 500,000 years ago. While wood preservation is poor, primatologist Craig Stanford suggests that chimpanzee spear use implies early humans also employed wooden spears, possibly 5 million years ago. The earliest surviving wooden hunting spears, the Schöningen spears from Germany, date to around 300,000 years ago, associated with Homo heidelbergensis.

The “hunting hypothesis” posits a direct link between the emergence of behavioral modernity in the Middle Paleolithic and hunting, encompassing aspects such as mating behavior, language development, culture, religion, mythology, and animal sacrifice. Conversely, sociologist David Nibert argues that organized animal hunting undermined the communal, egalitarian nature of early human societies. He suggests that the status of women and less powerful males declined as male status became intertwined with hunting success, potentially increasing violence within these societies.

Yet, archaeological discoveries challenge simplistic narratives; 9,000-year-old remains of a female hunter, complete with projectile points and animal processing implements, were unearthed at the Andean site of Wilamaya Patjxa in Peru. This finding underscores the diverse roles individuals played in early subsistence strategies. The Upper Paleolithic to Mesolithic periods further reveal hunting’s profound environmental impact.

Evidence suggests that hunting might have been a significant factor contributing to the Holocene extinction of megafauna and their subsequent replacement by smaller herbivores. Humans are believed to have played a substantial role in the extinction of Australian megafauna, which were widespread before human occupation. Crucially, hunting formed the backbone of hunter-gatherer societies before the domestication of livestock and the advent of agriculture, which began approximately 11,000 years ago in certain regions.

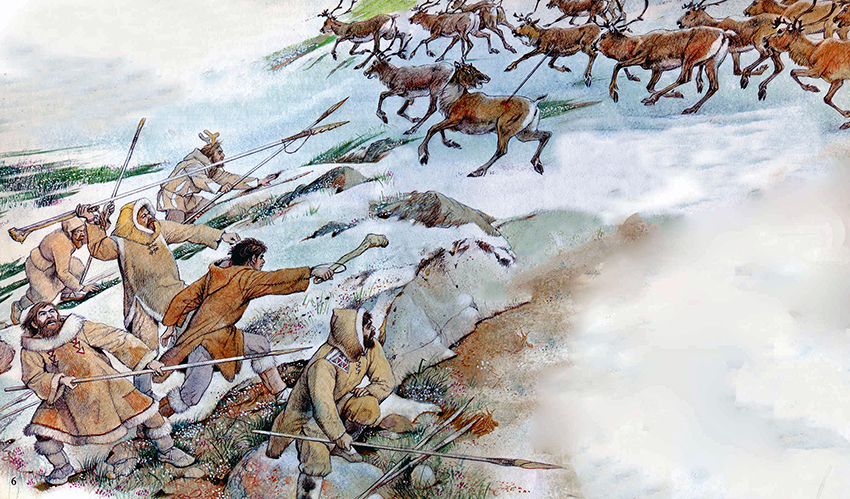

During the Upper Paleolithic, hunting weapons diversified beyond the spear to include the atlatl, a spear-thrower, appearing over 30,000 years ago, and the bow, developed 18,000 years ago. By the Mesolithic, hunting strategies became more sophisticated with these far-reaching weapons and the domestication of the dog around 15,000 years ago. Early evidence of mammoth hunting in Asia with spears dates to approximately 16,200 years ago, while a sharp flint piece from Bjerlev Hede in central Jutland, dated around 12,500 BC, is considered Denmark’s oldest hunting tool.

Many animal species have been historically hunted, but one theory highlights the importance of caribou and wild reindeer in North America and Eurasia as “the species of single greatest importance in the entire anthropological literature on hunting,” though their significance varied geographically. Mesolithic hunter-gathering lifestyles persisted in parts of the Americas, Sub-Saharan Africa, Siberia, and all of Australia until the European Age of Discovery, and a few tribal societies still maintain them today, albeit in rapid decline.