India, officially known as the Republic of India, stands as a colossal entity in South Asia, marking its identity as the world’s seventh-largest country by area. Since 2023, it has embraced the distinction of being the most populous nation globally, and remarkably, it has held the mantle of the world’s most populous democracy since gaining independence in 1947.

This vast land is geographically defined by the Indian Ocean to its south, the Arabian Sea to the southwest, and the Bay of Bengal to the southeast, while sharing intricate land borders with Pakistan to the west, China, Nepal, and Bhutan to the north, and Bangladesh and Myanmar to the east. Its strategic position in the Indian Ocean places it in proximity to Sri Lanka and the Maldives, with its Andaman and Nicobar Islands extending a maritime boundary with Thailand, Myanmar, and Indonesia.

The very name of this ancient land, “India,” echoes through history, derived from the Classical Latin “India,” which referred to South Asia and regions further east. This, in turn, traced its lineage from Hellenistic Greek, Ancient Greek, and Old Persian terms, ultimately stemming from the Sanskrit “Sindhu,” meaning ‘river,’ specifically the mighty Indus River and its fertile southern basin. The Ancient Greeks aptly called its inhabitants “Indoi,” or ‘the people of the Indus.’

Complementing “India,” the term “Bharat” is deeply embedded in both Indian epic poetry and the Constitution of India, reflecting a modern rendering of the historical “Bharatavarsha,” which originally denoted North India. This name gained significant currency from the mid-19th century as a cherished native identifier for the country. Another significant name, “Hindustan,” a Middle Persian term for India, found widespread popularity by the 13th century, becoming a common designation during the Mughal Empire, encompassing regions from the northern Indian subcontinent to its near entirety.

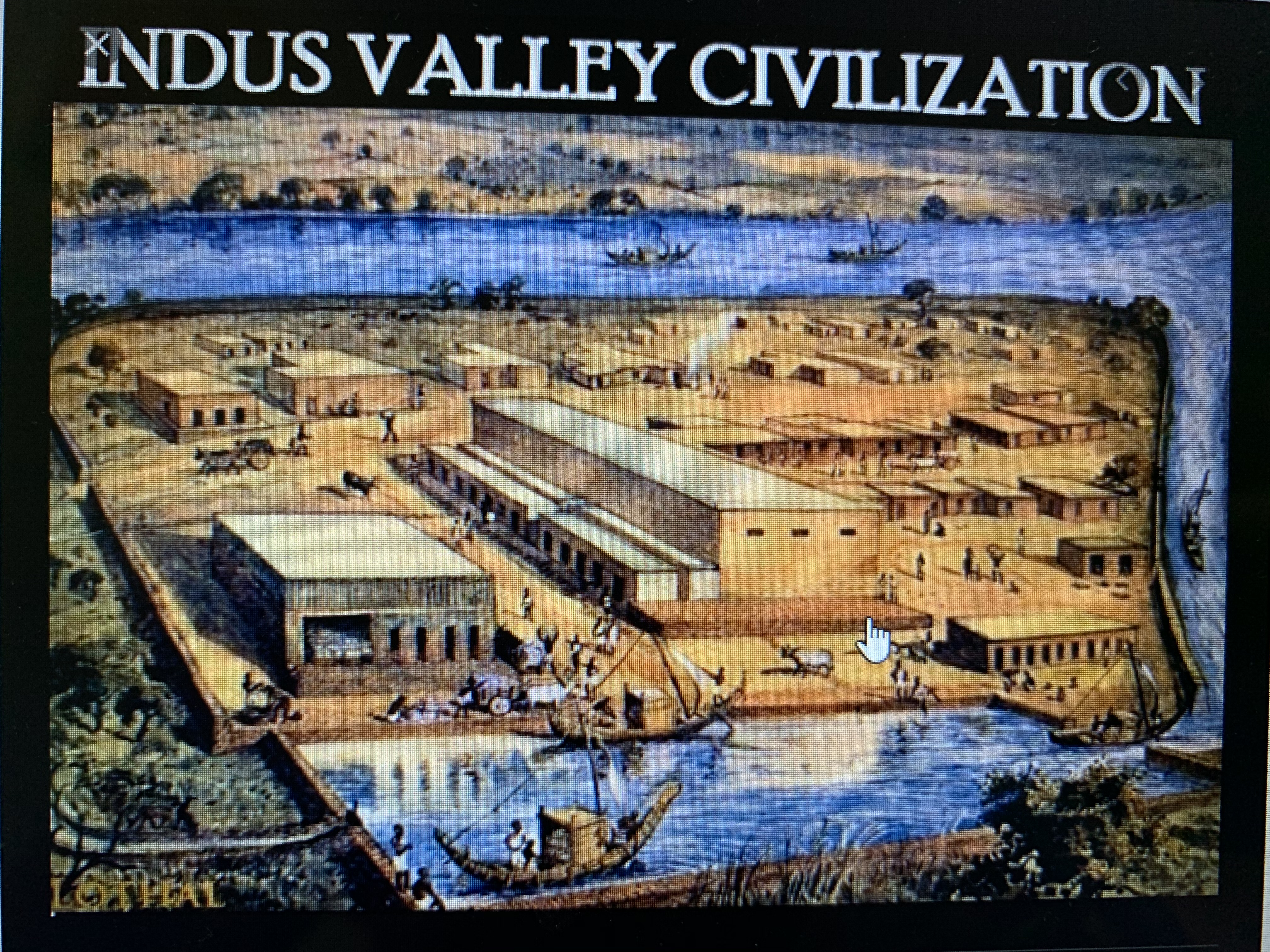

The human story in India commenced an astonishing 55,000 years ago, with modern humans migrating from Africa to the Indian subcontinent. This long occupation, largely characterized by isolation as hunter-gatherers, fostered an unparalleled diversity within the region. Around 9,000 years ago, settled life began to emerge on the western fringes of the Indus river basin, setting the stage for the magnificent Indus Valley Civilisation of the third millennium BCE.

By 1200 BCE, an archaic form of Sanskrit, an Indo-European language, had gracefully diffused into India from the northwest, its sacred hymns recording the profound early dawnings of Hinduism. This linguistic and spiritual diffusion led to the supplantation of India’s pre-existing Dravidian languages in the northern territories. By 400 BCE, the intricate social structure of caste had emerged within Hinduism, while Buddhism and Jainism arose, proclaiming revolutionary social orders unlinked to heredity.

Early political consolidations gave birth to the loosely structured Maurya and Gupta Empires, periods that saw widespread creativity suffusing the era. However, this progress was tempered by a decline in the status of women and the unfortunate institutionalization of untouchability. Further south, the Middle kingdoms played a crucial role in exporting Dravidian language scripts and their rich religious cultures to the burgeoning kingdoms of Southeast Asia.

The early medieval era witnessed the establishment of diverse faiths like Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism along India’s southern and western coasts, adding layers to its already complex cultural mosaic. The second millennium brought intermittent incursions by Muslim armies from Central Asia into India’s northern plains, leading to the formation of the Delhi Sultanate. This powerful sultanate drew northern India into the expansive, cosmopolitan networks of medieval Islam, facilitating a significant cultural exchange.

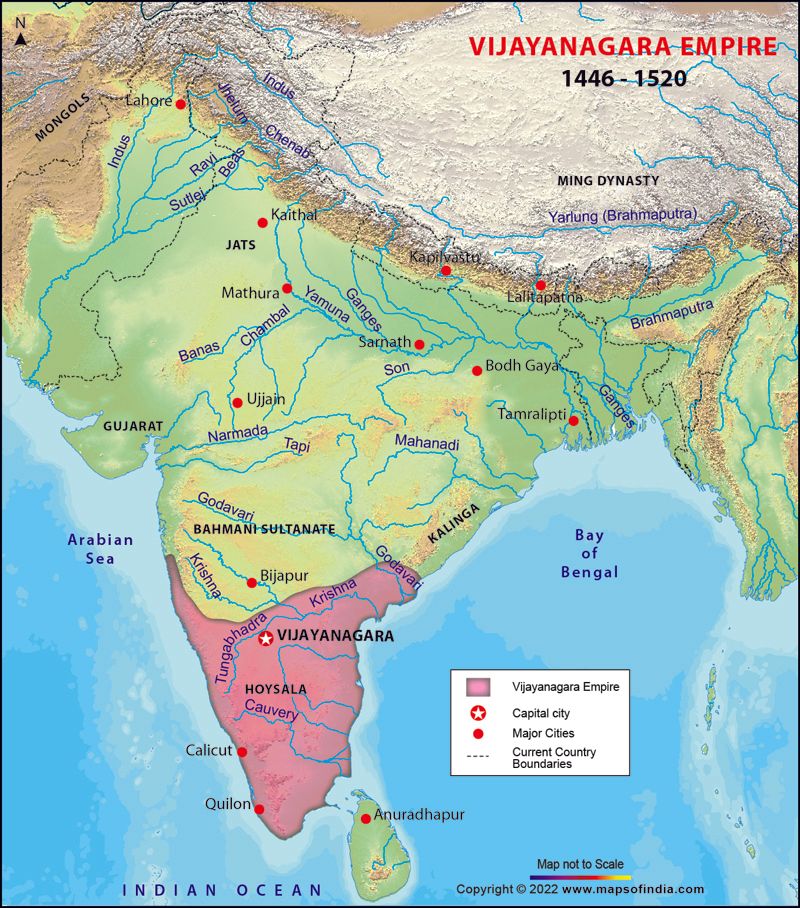

In the southern reaches of India, the Vijayanagara Empire rose, forging a long-lasting composite Hindu culture that left an indelible mark on the region. Concurrently, in the Punjab, Sikhism emerged, offering a distinct spiritual path that rejected institutionalized religion. The Mughal Empire, a subsequent dominant force, ushered in two centuries of unparalleled economic expansion and relative peace, gracing the land with a truly rich architectural legacy that continues to mesmerize.

Yet, this era of prosperity gradually shifted with the expanding influence of the British East India Company. The Company’s rule transformed India into a colonial economy, diverting its focus from manufacturing to supplying raw materials for the British Empire, but notably, it also consolidated India’s sovereignty under a single administrative umbrella. British Crown rule, commencing in 1858, brought about technological changes and introduced modern ideas of education and public life, albeit with a slow and gradual granting of rights to Indians.

A powerful nationalist movement began to coalesce in India, distinguishing itself as the first of its kind in the non-European British Empire, inspiring similar movements across the globe. This movement, prominently noted for its commitment to nonviolent resistance after 1920, became the primary force in ending British rule. The momentous year of 1947 saw the British Indian Empire partitioned into two independent dominions: a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan, a division tragically accompanied by immense loss of life and unprecedented migration.

Since 1950, India has proudly stood as a federal republic, governed through a robust democratic parliamentary system, embodying a truly pluralistic, multilingual, and multi-ethnic society. Its demographic journey has been astounding, with the population soaring from 361 million in 1951 to over 1.4 billion by 2023. This growth has been paralleled by significant economic transformation; what was once a comparatively destitute country in 1951 has blossomed into a fast-growing major economy and a global hub for information technology services, nurturing an expanding middle class.

India’s cultural footprint has also expanded dramatically, with Indian movies and music increasingly influencing global culture, showcasing its vibrant creative spirit. While the nation has made remarkable strides in reducing its poverty rate, this progress has unfortunately come at the cost of increasing economic inequality, a challenge the nation continues to grapple with. As a nuclear-weapon state that ranks high in military expenditure, India navigates complex geopolitical waters, including unresolved disputes over Kashmir with its neighbors, Pakistan and China, lingering since the mid-20th century.

The nation also faces significant socio-economic challenges, including persistent gender inequality, pervasive child malnutrition, and rising levels of air pollution, which highlight the ongoing need for comprehensive development. Despite these hurdles, India’s sustained democratic freedoms stand as a unique beacon among the world’s newer nations. Its journey toward freedom from want for its disadvantaged population remains an ongoing and paramount goal, even amidst its recent economic successes, with significant strides in poverty reduction largely attributed to government welfare programs as of 2025.

India’s geography is as diverse and dynamic as its history, encompassing the bulk of the Indian subcontinent and resting atop the Indian tectonic plate. The dramatic geological processes that shaped India began 75 million years ago, as the Indian Plate drifted northeastward, spurred by seafloor spreading. This immense movement eventually led to the Indian continental crust under-thrusting Eurasia, a monumental collision that uplifted the majestic Himalayas.

Immediately south of the Himalayas, this plate movement carved out a vast, crescent-shaped trough, which was rapidly filled with river-borne sediment, forming the expansive Indo-Gangetic Plain, the fertile heartland of northern India. The ancient Aravalli range, stretching from the Delhi Ridge southwestward, represents the original Indian plate emerging above this sediment, while to its west lies the formidable Thar Desert, its eastward spread checked by the Aravallis.

The remaining Indian Plate forms peninsular India, the oldest and geologically most stable part of the country, extending north to the Satpura and Vindhya ranges. These parallel mountain chains traverse from the Arabian Sea coast in Gujarat to the coal-rich Chota Nagpur Plateau in Jharkhand. Further south, the Deccan Plateau, flanked by the Western and Eastern Ghats, hosts some of the country’s oldest rock formations, dating back over a billion years.

Strategically positioned north of the equator, India lies between 6° 44′ and 35° 30′ north latitude and 68° 7′ and 97° 25′ east longitude. Its extensive coastline stretches 7,517 kilometers, with 5,423 kilometers belonging to peninsular India and 2,094 kilometers to its island chains of Andaman, Nicobar, and Lakshadweep. The mainland coastline features a diverse landscape: 43% sandy beaches, 11% rocky shores including cliffs, and 46% mudflats or marshy shores, according to Indian naval hydrographic charts.

Major Himalayan-origin rivers, including the Ganges and the Brahmaputra, flow substantially through India, both ultimately draining into the Bay of Bengal. Important tributaries of the Ganges, such as the Yamuna and the Kosi, play vital roles in the hydrological system, though the Kosi’s extremely low gradient often leads to severe floods and course changes due to long-term silt deposition. Peninsular rivers like the Godavari, Mahanadi, Kaveri, and Krishna also drain into the Bay of Bengal, while the Narmada and Tapti flow westward into the Arabian Sea, their steeper gradients preventing widespread flooding.

Coastal features include the marshy Rann of Kutch in western India and the alluvial Sundarbans delta in eastern India, shared with Bangladesh. India also boasts two archipelagos: the Lakshadweep, a collection of coral atolls off the southwestern coast, and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a volcanic chain situated in the Andaman Sea. India’s climate is profoundly shaped by the Himalayas, which block cold Central Asian winds, keeping the subcontinent warmer than other regions at similar latitudes, and the Thar Desert, which is crucial in attracting the moisture-laden southwest summer monsoon winds that deliver the majority of India’s rainfall between June and October.

Four major climatic groupings characterize India: tropical wet, tropical dry, subtropical humid, and montane. Temperatures have risen by 0.7 °C between 1901 and 2018, with climate change often considered the cause, leading to the retreat of Himalayan glaciers and adversely affecting the flow rates of major rivers like the Ganges and Brahmaputra. Current projections suggest a marked increase in the number and severity of droughts in India by the end of the present century, underscoring urgent environmental concerns.

India is a designated megadiverse country, one of only 17 globally that exhibit high biological diversity and a significant number of exclusively indigenous, or endemic, species. It is home to an impressive 8.6% of all mammal species, 13.7% of bird species, 7.9% of reptile species, 6% of amphibian species, 12.2% of fish species, and 6.0% of all flowering plant species. A remarkable one-third of Indian plant species are endemic, further highlighting its unique ecological heritage.

Within India’s borders lie four of the world’s 34 biodiversity hotspots, regions characterized by both high endemism and significant habitat loss. Its densest forests, such as the tropical moist forests of the Andaman Islands, the Western Ghats, and Northeast India, cover approximately 3% of its land area. Moderately dense forests, with canopy densities between 40% and 70%, occupy 9.39% of the land, predominantly found in the temperate coniferous forests of the Himalayas, the moist deciduous sal forests of eastern India, and the dry deciduous teak forests of central and southern India.

Two natural zones of thorn forest exist, one in the Deccan Plateau and the other in the western Indo-Gangetic plain, though the latter has been transformed into rich agricultural land by irrigation, obscuring its original features. Notable indigenous trees include the astringent Azadirachta indica, or neem, widely used in rural herbal medicine, and the luxuriant Ficus religiosa, or peepul, depicted on ancient Mohenjo-daro seals and famously associated with Buddha’s enlightenment. Many Indian species trace their lineage to Gondwana, the ancient southern supercontinent from which India separated over 100 million years ago.

The subsequent collision with Eurasia initiated a mass exchange of species, though later volcanism and climatic changes led to the extinction of many endemic Indian forms. Mammals later entered India from Asia through two zoogeographic passes, which lowered endemism among India’s mammals to 12.6%, contrasting sharply with 45.8% among reptiles and 55.8% among amphibians. Endemic species include the vulnerable hooded leaf monkey and the threatened Beddome’s toad of the Western Ghats.

India is home to 172 IUCN-designated threatened animal species, representing 2.9% of endangered forms, including the iconic Bengal tiger and the Ganges river dolphin. Critically endangered species include the gharial, the great Indian bustard, and the Indian white-rumped vulture, which faced near extinction due to ingesting carrion from diclofenac-treated cattle. The historic thorn forests of Punjab, once home to blackbuck preyed upon by the now-extinct Asiatic cheetah, highlight past ecological shifts.

The pervasive and ecologically devastating human encroachment of recent decades has critically endangered Indian wildlife. In response, India has significantly expanded its system of national parks and protected areas, first established in 1935. Landmark legislation such as the Wildlife Protection Act and Project Tiger, enacted in 1972, and the Forest Conservation Act of 1980 (with 1988 amendments), safeguard crucial wilderness. The nation proudly hosts over five hundred wildlife sanctuaries, eighteen biosphere reserves (four part of the World Network), and eighty-nine wetlands registered under the Ramsar Convention, demonstrating a profound commitment to conservation.

India operates as a parliamentary republic characterized by a multi-party system, a testament to its vibrant democracy. It recognizes six national parties, prominently including the Indian National Congress (INC) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), alongside over 50 regional parties. The Congress traditionally occupies the ideological center in Indian political culture, while the BJP is identified as right-wing to far-right, illustrating the broad spectrum of its political discourse.

From 1950 through the late 1980s, the Congress party consistently held a majority in India’s parliament, establishing a long period of single-party dominance. Subsequently, power increasingly became shared with the BJP and influential regional parties, necessitating the formation of multi-party coalition governments at the center, reflecting a more diversified political landscape.

In the early general elections of 1951, 1957, and 1962, the Congress, under the leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru, secured resounding victories. Following Nehru’s passing in 1964, Lal Bahadur Shastri briefly served as prime minister, succeeded in 1966 by Indira Gandhi, Nehru’s daughter, who led the Congress to electoral triumphs in 1967 and 1971.

Public discontent following the state of emergency declared by Indira Gandhi in 1975 led to the Congress being voted out of power in 1977, with the Janata Party, which had opposed the emergency, forming the government. This government, however, lasted only two years, with Morarji Desai and Charan Singh serving as prime ministers. The Congress returned to power in 1980, and upon Indira Gandhi’s assassination, she was succeeded by Rajiv Gandhi, who won easily in the subsequent elections that year.

The 1989 elections saw a National Front coalition, led by the Janata Dal in alliance with the Left Front, come to power, though it lasted just under two years, with V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar serving as prime ministers. In the 1991 Indian general election, the Congress, emerging as the largest single party, formed a minority government led by P. V. Narasimha Rao, navigating a period of political fluidity.

Following the 1996 general election, the BJP briefly formed a government, which was succeeded by United Front coalitions reliant on external political support, during which H.D. Deve Gowda and I.K. Gujral served as prime ministers. In 1998, the BJP successfully formed a coalition, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee, which made history by becoming the first non-Congress coalition government to complete a full five-year term, marking a significant shift in Indian politics.

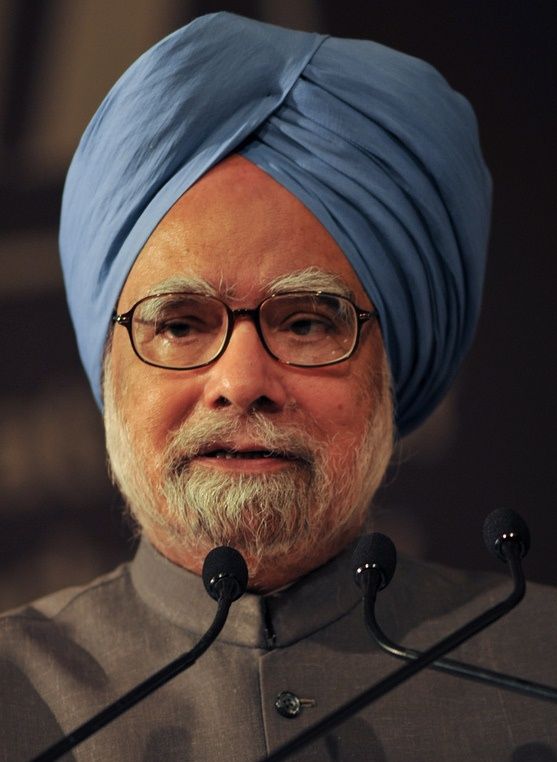

The 2004 Indian general elections saw no single party achieve an absolute majority, yet the Congress emerged as the largest single party, forming another successful coalition: the United Progressive Alliance (UPA), supported by left-leaning parties and MPs who opposed the BJP. The UPA further consolidated its position in the 2009 general election with increased numbers, no longer requiring external support from India’s communist parties.

Manmohan Singh, as prime minister, achieved a remarkable feat by being re-elected for a consecutive five-year term, a distinction not seen since Jawaharlal Nehru in 1957 and 1962. The 2014 general election marked another historical turning point, with the BJP becoming the first political party since 1984 to win an absolute majority. This trend continued in the 2019 general election, where the BJP again secured an absolute majority. In the 2024 general election, a BJP-led NDA coalition formed the government, with Narendra Modi, a former chief minister of Gujarat, serving as prime minister in his third term since May 26, 2014, signifying a prolonged period of stable governance.

India functions as a federation with a parliamentary system, meticulously governed under the Constitution of India. The principle of federalism in India delineates the power distribution between the union and the states. Traditionally described as “quasi-federal” due to a strong center and relatively weaker states, India’s form of government has shown a discernible shift towards greater federalism since the late 1990s, driven by significant political, economic, and social changes.

The Government of India is structured into three distinct branches: the Executive, the Legislature, and the Judiciary. The President of India serves as the ceremonial head of state, elected indirectly for a five-year term by an electoral college comprising members of national and state legislatures. The Prime Minister of India, in contrast, is the head of government and wields most executive power, appointed by the president and supported by the party or political alliance holding a majority of seats in the lower house of parliament.

The executive arm of the Indian government includes the president, the vice-president, and the Union Council of Ministers, with the cabinet serving as its executive committee, all headed by the prime minister. A crucial aspect of this system is that any minister holding a portfolio must be a member of one of the houses of parliament, ensuring direct accountability. In this Westminster-style parliamentary system, the executive is subordinate to the legislature, meaning the prime minister and their council are directly responsible to the lower house of the parliament, with civil servants acting as permanent executives to implement all decisions.

India’s legislature is a bicameral parliament, operating under the Westminster-style system. It comprises an upper house, the Rajya Sabha (Council of States), and a lower house, the Lok Sabha (House of the People). The Rajya Sabha is a permanent body of 245 members, serving staggered six-year terms with elections held every two years. Most members are elected indirectly by state and union territorial legislatures, with numbers proportional to their state’s share of the national population, ensuring regional representation.

The Lok Sabha, or House of the People, consists of 543 members, who are directly elected by popular vote among citizens aged at least 18, representing single-member constituencies for five-year terms. To ensure inclusive representation, several seats from each state are reserved for candidates from Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, in proportion to their population within that state.

India’s judicial system is a three-tier, unitary, and independent structure, headed by the Supreme Court and its Chief Justice of India. Below the Supreme Court are 25 high courts, followed by a vast network of trial courts. The Supreme Court holds original jurisdiction over cases involving fundamental rights and disputes between states and the center, and also possesses appellate jurisdiction over the high courts. Crucially, it has the power to strike down union or state laws that contravene the constitution and to invalidate any government action it deems unconstitutional, acting as the ultimate guardian of the nation’s foundational legal document.

As a federal union, India is meticulously divided into 28 states and 8 union territories, each with its own administrative structure. All states, along with the union territories of Jammu and Kashmir, Puducherry, and the National Capital Territory of Delhi, feature elected legislatures and governments that adhere to the Westminster system. The remaining five union territories are administered directly by the central government through appointed administrators, reflecting a blend of decentralized governance and central control within this vast and diverse nation.

From its ancient origins to its modern standing, India’s journey is a testament to resilience, adaptation, and an enduring spirit of diversity. It is a land where millennia of history, intricate cultural layers, and profound spiritual traditions converge with the ambitions of a dynamic, rapidly developing economy. This complex tapestry, woven with triumphs and ongoing challenges, solidifies India’s pivotal role on the global stage, making it a nation of immense consequence and continuous evolution.