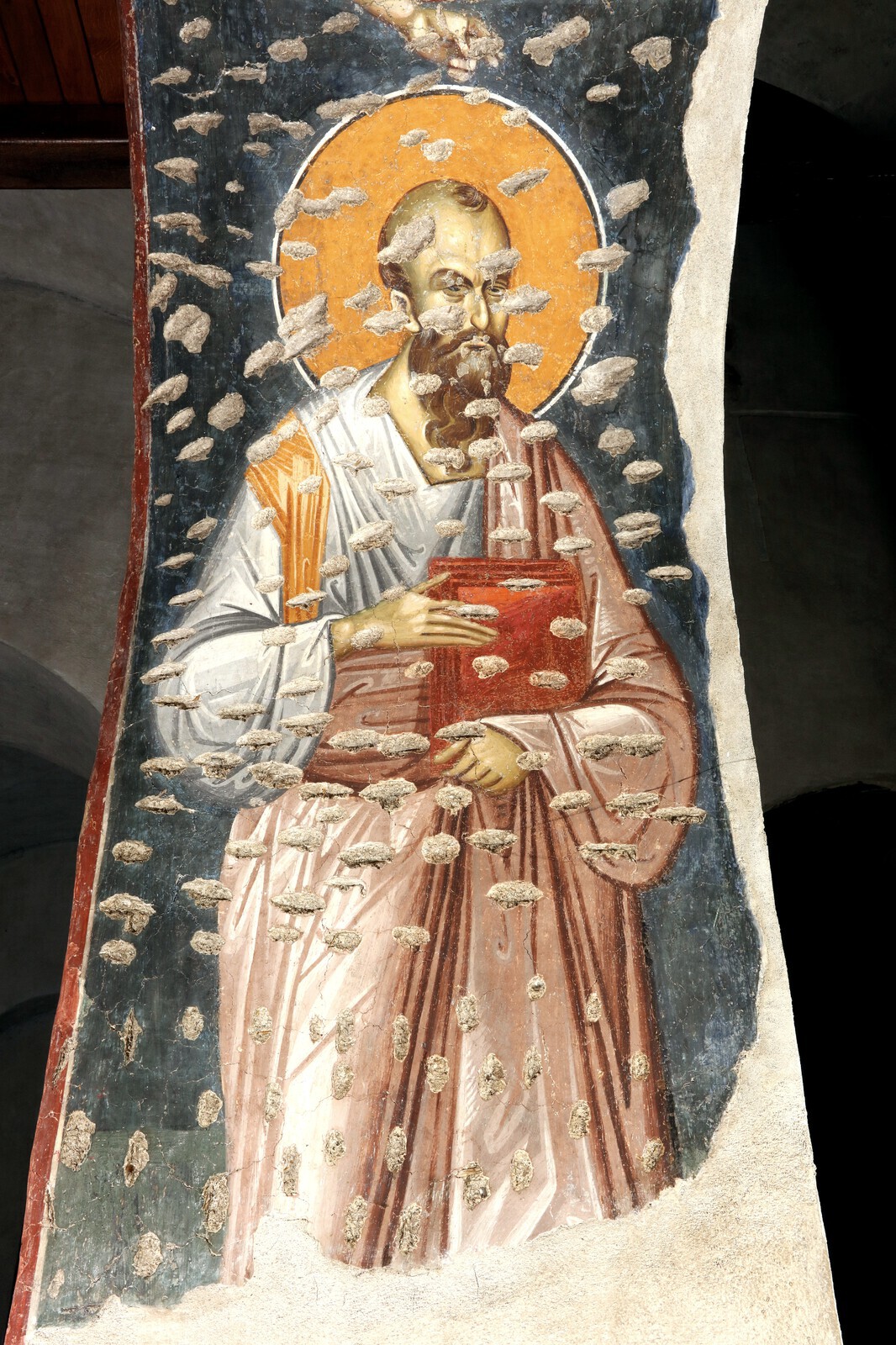

Paul the Apostle stands as an colossal figure in the annals of early Christianity, a personality whose influence reverberates through millennia, shaping theology, worship, and the very fabric of Western and Eastern Christian traditions. Often referred to simply as Paul, or by his Jewish name, Saul of Tarsus, his life story is one of dramatic transformation, relentless missionary zeal, and profound intellectual contribution. His journey from zealous persecutor to fervent evangelist is not merely a biographical sketch, but a foundational narrative that underpins much of the New Testament.

The primary lens through which we apprehend Paul’s extraordinary life and prolific works are his own letters and the compelling account found in the Acts of the Apostles. These texts, while occasionally offering divergent perspectives that have fueled scholarly debate for centuries, collectively paint a portrait of an individual driven by an unwavering conviction in the resurrected Christ. To delve into Paul’s biography is to witness the nascent stages of a world-changing movement, guided by a man who, despite never knowing Jesus during his earthly ministry, became arguably its most influential interpreter and architect.

This extensive journey through Paul’s life aims to unpack the multifaceted layers of his identity, the crucible of his early experiences, and the pivotal moments that transformed him into the “Apostle to the Gentiles.” From his Roman citizenship and Pharisaic upbringing to his dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus and the ensuing immediate call to ministry, we will explore the forces that shaped this towering figure, illuminating the sheer scale of his dedication and the enduring legacy of his initial, foundational endeavors.

1. **Paul’s Dual Identity: Saul of Tarsus and Paulus**The man we know as Paul bore two names, a duality reflecting his unique position bridging Jewish tradition and the broader Greco-Roman world. His Jewish name was “Saul,” likely a homage to the biblical King Saul, who, like the Apostle, hailed from the Tribe of Benjamin. This name rooted him firmly within his heritage, signifying his identity as a Hebrew among Hebrews, a devout Jew from Tarsus.

However, Paul also possessed a Latin name, “Paulus,” meaning “small.” This was not, as often mistakenly believed, a consequence of his conversion experience, but rather a second name, employed for effective communication within a Greco-Roman context. The Acts of the Apostles explicitly states his Roman citizenship, a status that afforded him certain rights and privileges, and indeed, proved crucial at various junctures of his ministry and trials.

It was typical for Jews of that era, especially those residing in diaspora communities like Tarsus, to carry both a Hebrew and a Latin or Greek name. This practice facilitated interaction across cultural lines, underscoring the cosmopolitan environment Paul inhabited. Jesus himself addressed him as “Saul, Saul” in “the Hebrew tongue” in the Acts of the Apostles, during his conversion vision on the road to Damascus, yet later, “the Lord” referred to him as “Saul, of Tarsus” in a vision to Ananias.

The shift to “Paul” is first recorded in Acts 13:9 on the island of Cyprus, much later than his conversion, with the author of Luke-Acts noting that “Saul, who also is called Paul” indicated their interchangeability. It was Paul’s clear preference, as all other biblical books mentioning him, including his own epistles, use the name Paul. This adoption of his Roman name was a strategic component of his missionary approach, designed to foster ease and relatability with his diverse audience, a principle he articulated in 1 Corinthians 9:19–23, adapting his message to different groups to win as many as possible.

2. **The Primary Sources of His Life: Letters and Acts**To truly comprehend the intricate tapestry of Paul’s life, scholars and devotees alike turn to two foundational New Testament sources: Paul’s own epistles and the historical narrative provided in the Acts of the Apostles. These documents are indispensable, offering a unique dual perspective—an autobiographical account from Paul’s intensely personal letters, and a third-person narrative from the pen of Luke, the author of Acts.

Paul’s epistles, while immensely rich in theological depth and practical instruction, offer relatively sparse details concerning his pre-conversion past. They are primarily focused on articulating Christian doctrine, addressing specific issues within the burgeoning churches he founded, and defending his apostolic authority. Nonetheless, they provide crucial autobiographical snippets, particularly regarding his conversion experience and subsequent interactions with the Jerusalem church, offering a direct window into his mindset and the immediate aftermath of his radical shift.

In contrast, the Acts of the Apostles presents a more comprehensive, though not exhaustive, chronological account of Paul’s life and missionary activities. It documents his travels, preaching, and various miracles, effectively covering approximately half of its entire content. However, even Acts omits certain aspects, such as his probable, yet undocumented, execution in Rome, and some scholars have pointed to apparent contradictions between Acts and Paul’s epistles, particularly concerning the frequency of his visits to Jerusalem.

Despite these perceived discrepancies, recent scholarship has increasingly challenged the notion of a stark divergence between the Paul of Acts and the Paul of the letters, suggesting a more nuanced harmony. Beyond these canonical texts, a constellation of external sources—including Clement of Rome’s epistle to the Corinthians (late 1st/early 2nd century), Ignatius of Antioch’s epistles (early 2nd century), Polycarp’s epistle to the Philippians (early 2nd century), and Eusebius’s Historia Ecclesiae—along with various apocryphal acts and epistles from later centuries, further augment our understanding, attesting to Paul’s pervasive influence even if their historical reliability varies.

Read more about: Unlock Your Digital Shield: 15 Essential Cybersecurity Tricks Everyone Needs to Master Today

3. **His Early Life and Pharisaic Roots**The formative years of Paul, or Saul, were steeped in a rich confluence of Jewish tradition and Hellenistic culture, setting the stage for his future role as an apostle to both Jews and Gentiles. He was likely born between 5 BC and 5 AD in Tarsus, a prominent city within the Roman province of Cilicia. Tarsus was not merely a provincial town; it was a significant center of trade on the Mediterranean coast and was celebrated for its academy, having been one of Asia Minor’s most influential cities since the era of Alexander the Great.

Paul proudly identified himself as being “of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of the Hebrews; as touching the law, a Pharisee.” This declaration underscores his impeccable Jewish lineage and his rigorous adherence to Pharisaic traditions. The Bible offers scant details about his immediate family, though Acts quotes him stating he was “a Pharisee, born of Pharisees,” indicating a generational commitment to this strict sect of Judaism, which was known for its meticulous observance of the Law. His family’s piety and attachment to Pharisaic observances were evidently deeply ingrained.

Furthermore, Paul was a Roman citizen by birth, a status potentially inherited from ancestors who may have been freedmen from among the thousands of Jews whom Pompey took as slaves in 63 BC. Roman citizenship was granted upon emancipation to slaves of Roman citizens, providing a plausible explanation for his birthright. This dual heritage—a devout Jewish Pharisee with Roman citizenship from a Hellenistic city—equipped him with a unique cultural fluidity.

His education further distinguished him. While still relatively young, Paul was sent to Jerusalem to study under Gamaliel, an illustrious teacher of Jewish law. Although modern scholarship accepts this tutelage, some argue he wasn’t necessarily preparing to be a scholar of Jewish law in the traditional sense, and likely had no contact with the Hillelite school. The Acts also notes his profession as an artisan, involved in leather crafting or tent-making, a skill that would later connect him with Priscilla and Aquila, his crucial missionary partners. Paul’s fluency in Koine Greek, the language of his letters, combined with his probable Aramaic first language and his deep knowledge of Stoic philosophy, which he strategically employed to explain the Gospel to Gentile converts, all highlight a formidable intellectual background.

4. **The Persecutor of Early Christians**Before his dramatic encounter with the resurrected Christ, Paul’s life was characterized by an intense and zealous persecution of early Christians. He candidly admits in his own writings, such as those within the Galatians text, that he persecuted believers “beyond measure,” more specifically Hellenised diaspora Jewish members who had returned to the area of Jerusalem. This period of his life is often jarringly contrasted with his later role as Christianity’s foremost missionary, underscoring the profundity of his transformation.

The Acts of the Apostles, particularly in its introductory narratives concerning Paul’s early actions, details his participation in the persecution of early disciples of Jesus. He is specifically mentioned as taking an active, albeit endorsing, part in the martyrdom of Stephen, a Hellenised diaspora Jew. This involvement positions him firmly as an antagonist to the nascent Christian movement, viewing it as a dangerous heresy that threatened the purity of Judaism.

While Paul does not explicitly delineate the exact forms his persecution took, James Dunn suggests that his initial efforts were likely aimed at Greek-speaking “Hellenists.” These individuals, often diaspora Jews who had resettled in Jerusalem, held an “anti-Temple attitude” that set them apart from the “Hebrews” within the early Jewish Christian community, who continued their participation in the Temple cult. This distinction may have made the Hellenists a particular target for Paul’s zealous efforts to suppress what he perceived as a deviation from orthodox Judaism.

His fervor was such that he embarked on a mission to arrest Christians in Damascus, demonstrating a commitment to extinguishing the movement that transcended geographical boundaries. This period of his life, though dark, is essential for understanding the magnitude of his later conversion, as it highlights the depth of his conviction prior to his encounter with Jesus and provides a powerful testimony to the transformative power of faith.

Read more about: Saint Peter: A Definitive Chronicle of the Apostle’s Life, Leadership, and Enduring Spiritual Influence

5. **The Transformative Conversion on the Road to Damascus**The pivotal event that irrevocably altered the trajectory of Paul’s life, transforming him from a fierce persecutor to a dedicated apostle, was his conversion experience, dated by his own references in letters to between 31 and 36 AD. This dramatic encounter, famously occurring on the road to Damascus, serves as the spiritual and biographical epicenter of his narrative. It was not a gradual shift in perspective but a sudden, divine intervention that reshaped his entire worldview.

Paul himself recounts this monumental revelation in various epistles. In Galatians 1:16, he asserts that God “was pleased to reveal his son to me,” emphasizing the direct, personal nature of this divine intervention. Further, in 1 Corinthians 15:8, as he enumerates the post-resurrection appearances of Jesus, Paul states, “last of all, as to one untimely born, He appeared to me also,” acknowledging his unique and unexpected call to apostleship, distinct from those who had known Jesus during his earthly life.

The Acts of the Apostles provides a vivid and detailed account of this experience. While en route to Damascus with the intent of arresting Christians, “He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’ He asked, ‘Who are you, Lord?’ The reply came, ‘I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting’.” This direct confrontation with the ascended Christ left him blinded for three days, necessitating that he be led by hand into Damascus, a profound physical manifestation of his spiritual blindness prior to this encounter.

During these three days of sightlessness, Saul abstained from food and water, devoting himself to prayer. His healing came through Ananias of Damascus, who, guided by a vision, laid hands on him, declaring, “Brother Saul, the Lord, [even] Jesus, that appeared unto thee in the way as thou camest, hath sent me, that thou mightest receive thy sight, and be filled with the Holy Ghost.” Immediately, his sight was restored, he rose, and was baptized, marking the definitive commencement of his new life in Christ. This profound event, though its exact recounting differs slightly between Paul’s letters and Acts, remains the defining moment of his spiritual rebirth and apostolic commissioning.

Read more about: The Transformative Journey of Paul the Apostle: A Deep Dive into His Life, Conversion, and Enduring Theological Legacy

6. **Immediate Post-Conversion Ministry and Early Journeys**Following his miraculous conversion and baptism in Damascus, Paul did not immediately retreat or undergo a prolonged period of quiet contemplation; instead, Acts records that “immediately he proclaimed Jesus in the synagogues, saying, ‘He is the Son of God’.” This bold declaration, coming from a former persecutor, astonished all who heard him, prompting questions about whether he was the same man who had wreaked havoc in Jerusalem among Christians. Despite the skepticism and immediate danger, Paul’s strength in his new conviction only grew, as he “confounded the Jews who lived in Damascus by proving that Jesus was the Christ.”

Paul himself provides additional details regarding his initial movements in his letter to the Galatians. He recounts barely escaping death in Damascus and then journeying to Arabia, after which he returned to Damascus. This trip to Arabia, unmentioned elsewhere in the Bible, has led to theories suggesting a period of solitude and reflection, perhaps even a visit to Mount Sinai for meditations in the desert, echoing the prophetic calls of old. It was a time of direct revelation, as Paul explicitly stated that he received the Gospel “not from man, but directly by ‘the revelation of Jesus Christ’.”

Three years after his conversion, he embarked on his first recorded visit to Jerusalem, around 35 or 36 AD. During this visit, he met James, the brother of Jesus, and stayed with Simon Peter for a significant period of fifteen days. This interaction, though brief, provided a crucial connection to the leaders of the Jerusalem community and the eyewitnesses of Jesus’ life. Paul consistently asserted his almost total independence from this Jerusalem community, yet maintained an agreement with them on the fundamental nature and content of the Gospel.

This early ministry phase, spanning several years after his Damascus road experience, laid the groundwork for his future, extensive missionary endeavors. It was a period of both personal spiritual consolidation and initial, bold proclamations, setting the stage for the global spread of Christianity he would champion. His eagerness to bring material support from the various growing Gentile churches that he started to Jerusalem also highlights his commitment to unity and the well-being of the broader Christian body from the very outset.

7. **The First Missionary Journey: Spreading the Gospel Beyond Borders**The trajectory of Paul’s ministry profoundly shifted into an organized, extensive evangelistic endeavor with his first missionary journey, a groundbreaking expedition commissioned by the vibrant Christian community in Antioch. This journey, undertaken with Barnabas as his initial leader and companion, marked a concerted effort to spread the teachings of Jesus beyond the established Jewish communities. Their travels initially took them from Antioch to the island of Cyprus, where they encountered Elymas the magician, whom Paul famously rebuked and blinded for criticizing their teachings, showcasing his emerging apostolic authority. This dramatic incident underscored the spiritual battle inherent in their mission.

Continuing their journey, Paul and Barnabas then sailed to Perga in Pamphylia, a region in southern Asia Minor. It was at this point that John Mark, a crucial figure in the early church and later the author of the Gospel, decided to depart from the missionary team and return to Jerusalem, a decision that would later cause a significant disagreement between Paul and Barnabas. Despite this setback, Paul and Barnabas pressed onward, venturing into Pisidian Antioch, a city that would become a pivotal stage for their preaching.

Upon arriving in Pisidian Antioch, they attended the synagogue on the Sabbath, a customary practice for Jewish apostles seeking an audience. Invited by the leaders to speak, Paul delivered a compelling sermon that masterfully reviewed Israelite history, tracing it from their time in Egypt to the reign of King David. He then skillfully introduced Jesus as a descendant of David, divinely brought to Israel, and presented him as the promised Christos who offered forgiveness for sins. His message resonated deeply with both the Jews and the “God-fearing” Gentiles present, who eagerly invited them to speak further the following Sabbath.

Word of their message spread rapidly, and the next Sabbath saw almost the entire city gathering to hear Paul and Barnabas. This immense public interest, however, ignited opposition from some influential Jews who vehemently spoke against them, demonstrating the friction between traditional Jewish observance and the nascent Christian movement. Seizing this moment, Paul boldly announced a significant shift in his mission: from that point forward, his primary focus would be directed towards the Gentiles. After concluding this impactful journey, Paul returned to Antioch, their home base, where he remained for “a long time with the disciples,” consolidating the early gains of their missionary efforts. This first journey is traditionally dated between 46 and 49 AD, a period of immense foundational significance for the expansion of Christianity.

8. **Pivotal Confrontations: The Jerusalem Council and the Incident at Antioch**Following his initial missionary successes, a critical meeting transpired in Jerusalem, traditionally dated to 49 AD, which would profoundly shape the future direction of the early Christian movement. Known as the Council of Jerusalem, this gathering, described in Acts 15:2, convened Paul and Barnabas with the leaders of the Jerusalem church, including Peter, James (the brother of Jesus), and John—whom Paul reverently calls “Pillars of the Church.” The central and most contentious question on the agenda was whether Gentile converts to Christianity needed to undergo circumcision, a deeply ingrained Jewish custom and a significant barrier for many potential Gentile believers.

At this momentous council, after much debate, the Jerusalem leaders ultimately accepted Paul’s mission to the Gentiles, confirming that circumcision was not a prerequisite for salvation. This agreement was a monumental theological and practical victory for Paul’s Gentile mission, affirming the universality of the Gospel message. Paul himself, in his letter to the Galatians, references a visit to Jerusalem that some scholars equate with this council, highlighting his consistent assertion of agreement with the Jerusalem community regarding the fundamental nature and content of the Gospel, despite his claims of apostolic independence.

Despite the significant accord reached at the Council of Jerusalem, the practical implications of this decision led to another pivotal confrontation, the “Incident at Antioch.” Paul recounts how he later publicly challenged Peter, who had initially shared meals with Gentile Christians but then withdrew from them and separated himself when certain individuals from James’s circle arrived from Jerusalem. Peter’s reluctance to continue fellowshipping and eating with Gentile Christians who did not strictly adhere to Jewish dietary customs created a palpable division within the Antioch community, forcing the Gentile converts into a second-class status.

In a moment of intense theological and social import, Paul recounts directly confronting Peter “to his face, because he was clearly in the wrong.” Paul’s powerful rebuke articulated the hypocrisy of the situation, stating, “You are a Jew, yet you live like a Gentile and not like a Jew. How is it, then, that you force Gentiles to follow Jewish customs?” This incident laid bare the persistent tension between Jewish and Gentile practices within the nascent church, even after the Jerusalem Council. Paul also noted with disappointment that even Barnabas, his long-time traveling companion, sided with Peter in this dispute, underscoring the gravity of the division. The exact outcome of this confrontation remains debated among scholars, with Paul’s account in Galatians serving as the primary source, but the very act of the confrontation solidified Paul’s unwavering commitment to the integrity of the law-free Gospel for Gentiles.

9. **The Second Missionary Journey: Vision, Imprisonment, and Growth**Paul embarked on his second missionary journey from Jerusalem in late Autumn 49 AD, a journey catalyzed by the resolutions of the Council of Jerusalem. This ambitious undertaking, however, began with an unexpected internal conflict. While stopping in Antioch, Paul and his companion Barnabas had a “sharp argument” regarding whether to take John Mark with them, as John Mark had previously left them during the first journey and returned home. Unable to reconcile their differing views, Paul and Barnabas decided to separate, with Barnabas taking John Mark and sailing to Cyprus, while Paul chose Silas as his new traveling companion. This separation, though born of disagreement, effectively doubled the missionary outreach.

Paul and Silas initially revisited Tarsus, Paul’s birthplace, before continuing to Derbe and Lystra. In Lystra, they met Timothy, a young disciple who was highly regarded by the local believers. Paul, recognizing Timothy’s potential and commitment, decided to take him along, integrating him into the missionary team. Their initial plans were to preach the Gospel in the southwest portion of Asia Minor, but their direction dramatically changed following a divine intervention. During the night, Paul experienced a vision of a man from Macedonia standing and imploring him, “Come over to Macedonia and help us.” This clear spiritual directive altered their course, compelling Paul and his companions to leave for Macedonia, opening a new frontier for Christian evangelism in Europe.

Upon reaching Philippi, a prominent city in Macedonia, their ministry encountered immediate opposition. Paul cast a spirit of divination out of a servant girl, whose masters, benefiting financially from her soothsaying, were enraged by their loss of income. They seized Paul and Silas, dragging them before the authorities in the marketplace, leading to their unjust imprisonment. Despite their dire circumstances, an extraordinary event unfolded: a miraculous earthquake shook the prison, causing the gates to fall open. While they could have escaped, Paul and Silas remained, a decision that deeply impacted the jailer, leading to his conversion and the baptism of his entire household.

Following their release, Paul and his companions continued their journey, passing through Berea, where they found a receptive audience, and then on to Athens, the intellectual heart of the Greco-Roman world. In Athens, Paul engaged both Jews and “God-fearing” Greeks in the synagogue and courageously preached to the sophisticated Greek intellectuals gathered at the Areopagus, skillfully adapting his message to their philosophical context. From Athens, Paul pressed onward to Corinth, a bustling and cosmopolitan city, which would become a significant center for his ongoing ministry, demonstrating the relentless pace and expanding geographical reach of his second journey.

10. **Further Journeys and Consolidation: Corinth, Ephesus, and Beyond**The second missionary journey transitioned into a crucial period of consolidation and further expansion, particularly in the vibrant city of Corinth. Around 50–52 AD, Paul dedicated eighteen months to ministry in Corinth, a strategically important location due to its bustling port and diverse population. A key historical anchor for dating Paul’s life is the reference in Acts to Proconsul Gallio, whose tenure in Corinth helps ascertain the precise timing of Paul’s stay. It was here that Paul encountered Priscilla and Aquila, a Jewish Christian couple who would become invaluable partners in his missionary endeavors and steadfast supporters throughout his subsequent journeys. This dedicated couple later followed Paul to Ephesus, establishing one of the strongest and most faithful churches of that era, a testament to their collaborative ministry. Before departing Corinth in 52 AD, Paul stopped at the nearby village of Cenchreae to have his hair cut, likely in fulfillment of a vow, possibly signifying a Nazirite vow completed for a defined period.

Accompanied by Priscilla and Aquila, the missionaries then sailed to Ephesus, a major city in Asia Minor, where they briefly ministered. Paul then continued alone to Caesarea, where he “greeted the Church” before traveling north to Antioch, his long-standing Christian home base. He stayed in Antioch for “some time,” recuperating and likely strategizing for his next extensive undertaking. Some New Testament texts also suggest a visit to Jerusalem during this interval for one of the Jewish feasts, possibly Pentecost, with textual critics like Henry Alford considering this reference genuine and in alignment with later accounts of Paul’s visits.

Paul’s third missionary journey commenced with a focused effort to strengthen, teach, and minister to believers throughout the regions of Galatia and Phrygia, revisiting churches he had previously founded. His travels then led him to Ephesus, which had become an increasingly important hub of early Christianity. Paul resided in Ephesus for almost three years, possibly continuing his trade as a tent-maker to support himself, a consistent practice throughout his ministry. During this extensive stay, he performed numerous miracles, healing the sick and casting out demons, and meticulously organized missionary activity that extended to other regions, demonstrating his strategic foresight in spreading the Gospel. This fruitful period in Ephesus, however, culminated in an attack from a local silversmith, Demetrius, which sparked a pro-Artemis riot involving most of the city, forcing Paul’s departure.

During his extended residency in Ephesus, Paul penned at least four letters to the church in Corinth, addressing various theological and pastoral issues within that community. The Epistle to the Philippians is also generally believed to have been written from Ephesus, though some scholars posit a Roman imprisonment as its origin. After leaving Ephesus, Paul journeyed through Macedonia and into Achaea, spending approximately three months in Greece, most likely in Corinth, during 56–57 AD. It is widely accepted by commentators that Paul dictated his monumental Epistle to the Romans during this time, encapsulating his profound theological insights. He then prepared to continue to Syria but altered his plans, instead traveling back through Macedonia, reputedly due to a plot against him by certain Jews. Paul also documented in Romans 15:19 his extensive travels as far as Illyricum, though he likely referred to what was then known as Illyria Graeca, a division of the Roman province of Macedonia. On their return journey to Jerusalem, Paul and his companions visited various cities, including Philippi, Troas, Miletus, Rhodes, and Tyre. His arduous journey finally concluded with a stop in Caesarea, where he and his companions stayed with Philip the Evangelist, before his arrival in Jerusalem for what would be his final, fateful visit.

11. **The Final Visit to Jerusalem and Arrest**In 57 AD, upon the culmination of his extensive third missionary journey, Paul arrived in Jerusalem for what would prove to be his fifth and final visit. He brought with him a substantial collection of money gathered from the various Gentile churches he had established, intended as financial support for the local Christian community in Jerusalem, underscoring his commitment to unity and the well-being of the broader Christian body. The Acts of the Apostles records that he was initially warmly received by the believers in Jerusalem, a moment of fellowship after his arduous travels.

However, this period of reception quickly gave way to a precarious situation. Paul was warned by James and the elders that a formidable reputation had preceded him, indicating that he was perceived as being against the Law of Moses. They informed him, “they have been told about you that you teach all the Jews living among the Gentiles to forsake Moses, and that you tell them not to circumcise their children or observe the customs.” To counteract this dangerous misconception and demonstrate his respect for Jewish traditions, Paul underwent a purification ritual alongside four men who had vows, hoping that “all will know that there is nothing in what they have been told about you, but that you yourself observe and guard the law.”

As the seven days of the purification ritual were nearing their completion, a contingent of “Jews from Asia”—most likely from the Roman province of Asia where Paul had been extensively ministering—recognized him in the Temple precincts. They wrongly accused Paul of defiling the Temple by bringing Gentiles into its sacred areas, igniting a furious mob. Paul was seized and violently dragged out of the Temple by this angry crowd, narrowly escaping lynching. The uproar attracted the attention of the Roman tribune, who, along with centurions and soldiers, rushed to quell the disturbance.

Unable to ascertain Paul’s identity or the precise cause of the commotion amid the chaos, the tribune ordered him to be placed in chains. As he was about to be taken into the barracks, Paul, ever the strategist, requested permission to speak to the agitated people. Granted permission by the Romans, he proceeded to address the crowd, recounting his life story, including his Jewish heritage, his zealous persecution of Christians, and his dramatic conversion on the Damascus Road. For a time, they listened, but when he spoke of being sent to the Gentiles, the crowd erupted, shouting, “Away with such a fellow from the earth! For he should not be allowed to live.”

The tribune, still trying to understand the situation, ordered Paul to be brought into the barracks and interrogated under flogging. However, Paul immediately asserted his Roman citizenship, a status that legally protected him from such punishment without a trial. This crucial revelation halted the flogging. The next day, desperate to understand the accusations, the tribune released him from chains and convened the chief priests and the entire Sanhedrin (council) to hear Paul’s case. Paul skillfully used this platform to cause a disagreement between the Pharisees and Sadducees within the council, further complicating the charges against him. When this threatened to turn violent, the tribune again intervened, ordering his soldiers to extract Paul by force and return him to the barracks. The narrative of his escalating legal troubles continued as 40 Jews conspired to kill him, binding themselves by an oath not to eat or drink until Paul was dead. Fortunately, Paul’s nephew overheard this plot and immediately notified Paul, who in turn informed the tribune. Recognizing the severity of the threat, the tribune swiftly dispatched Paul under heavy guard to Caesarea, instructing two centurions to prepare “two hundred soldiers, seventy horsemen, and two hundred spearmen” to ensure his safe passage to Felix the governor. Thus, Paul was transported to Caesarea, where Governor Felix ordered him to be kept under guard in Herod’s headquarters. Five days later, the high priest Ananias and elders, accompanied by an attorney named Tertullus, presented their case against Paul to the governor. While Felix, who was “rather well informed about the Way” (referring to Christianity), adjourned the hearing, he kept Paul in custody for two years, granting him some liberty and allowing his friends to care for his needs. His imprisonment continued under the new governor, Porcius Festus. When Festus suggested sending Paul back to Jerusalem for further trial, Paul, leveraging his Roman citizenship once more, famously exercised his right to “appeal unto Caesar,” setting in motion his journey to Rome for judgment.

Read more about: Saint John the Apostle: Unpacking the Enduring Legacy of a New Testament Pillar

12. **Imprisonment in Rome and Final Witness**Paul’s journey to Rome, initiated by his appeal to Caesar, was itself an epic saga. According to Acts, while en route, he was dramatically shipwrecked on the island of Melita, widely identified as modern-day Malta. Here, the islanders displayed “unusual kindness,” building a fire to welcome the survivors amid the rain and cold. A memorable incident occurred when Paul, gathering brushwood for the fire, was bitten by a poisonous snake driven out by the heat. The islanders, seeing the snake fasten itself to his hand, concluded he must be a murderer, believing that even though he escaped the sea, “the goddess Justice has not allowed him to live.” However, Paul simply shook the snake off into the fire, suffering no ill effects, a miraculous event that deeply impressed the locals. Following this, he was met by Publius, the chief official of the island, and continued his ministry, performing healings before eventually resuming his voyage.

From Malta, Paul journeyed to Rome via several other ports, including Syracuse, Rhegium, and Puteoli, finally arriving in the imperial capital around 60 AD. Upon his arrival, Paul was placed under house arrest, where he would remain for another two years, according to the traditional account. The narrative of the Acts of the Apostles concludes with Paul in Rome, still awaiting trial but actively “preaching the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance from anyone” from his rented home.

While Acts provides no explicit mention of Paul’s death, other early Christian traditions and sources offer insights into his ultimate fate. Irenaeus, writing in the 2nd century, stated that Peter and Paul were the founders of the church in Rome and had appointed Linus as their succeeding bishop, although Acts does not depict Paul in such a hierarchical role within the Roman church. Rather, Paul played a significant, albeit supporting, part in the life and establishment of the Christian community in Rome.

Paul’s death is widely believed to have occurred after the Great Fire of Rome in July 64 AD, but before the end of Nero’s reign in 68 AD. New Testament scholar Eric Franklin views the omission of his death in Acts, despite the mention of James and Stephen’s martyrdoms, as a deliberate authorial choice. Pope Clement I, in his Epistle to the Corinthians, writes that Paul “had borne his testimony before the rulers” and subsequently “departed from the world and went unto the holy place, having been found a notable pattern of patient endurance,” implying a martyrdom. Ignatius of Antioch similarly notes that Paul was “martyred” without providing further details. Tertullian writes that Paul was “crowned with an exit like John,” though the specific John referred to is unclear.

More explicitly, Eusebius, quoting Dionysius of Corinth, argues that Peter and Paul were martyred “at the same time,” a sentiment echoed by Sulpicius Severus, who claimed Peter was crucified while Paul was beheaded. John Chrysostom provides an account of Nero imprisoning Paul but does not explicitly detail his execution, nor does he mention Peter. Lactantius simply states that Nero “crucified Peter, and slew Paul.” Jerome’s account suggests Paul was initially dismissed by Nero after a period of free custody, allowing him to preach the Gospel in the West, potentially including Spain, but that he was later re-imprisoned and, in “the fourteenth year of Nero” (around 67/68 AD), was ultimately “beheaded at Rome for Christ’s sake” on the same day as Peter, and buried on the Ostian way, marking the poignant conclusion to a life dedicated entirely to the propagation of the Christian faith.

Read more about: The Transformative Journey of Paul the Apostle: A Deep Dive into His Life, Conversion, and Enduring Theological Legacy

From persecutor to prisoner, from a zealot of the law to the architect of a faith beyond it, Paul’s life was a testament to transformation, relentless dedication, and intellectual prowess. His journeys across the Roman world, his theological insights articulated in his epistles, and his unwavering commitment in the face of immense adversity forged the bedrock of Christian thought and practice for millennia. His final days, culminating in martyrdom in Rome, served not as an end but as the ultimate seal on a legacy that continues to inspire, challenge, and shape believers across the globe, ensuring his status as arguably the most influential figure in Christian history after Jesus Christ himself. His extensive missionary endeavors, pivotal confrontations, and ultimate sacrifice established a blueprint for spreading the message, a testament to a lifelong obsession with the Good News.”