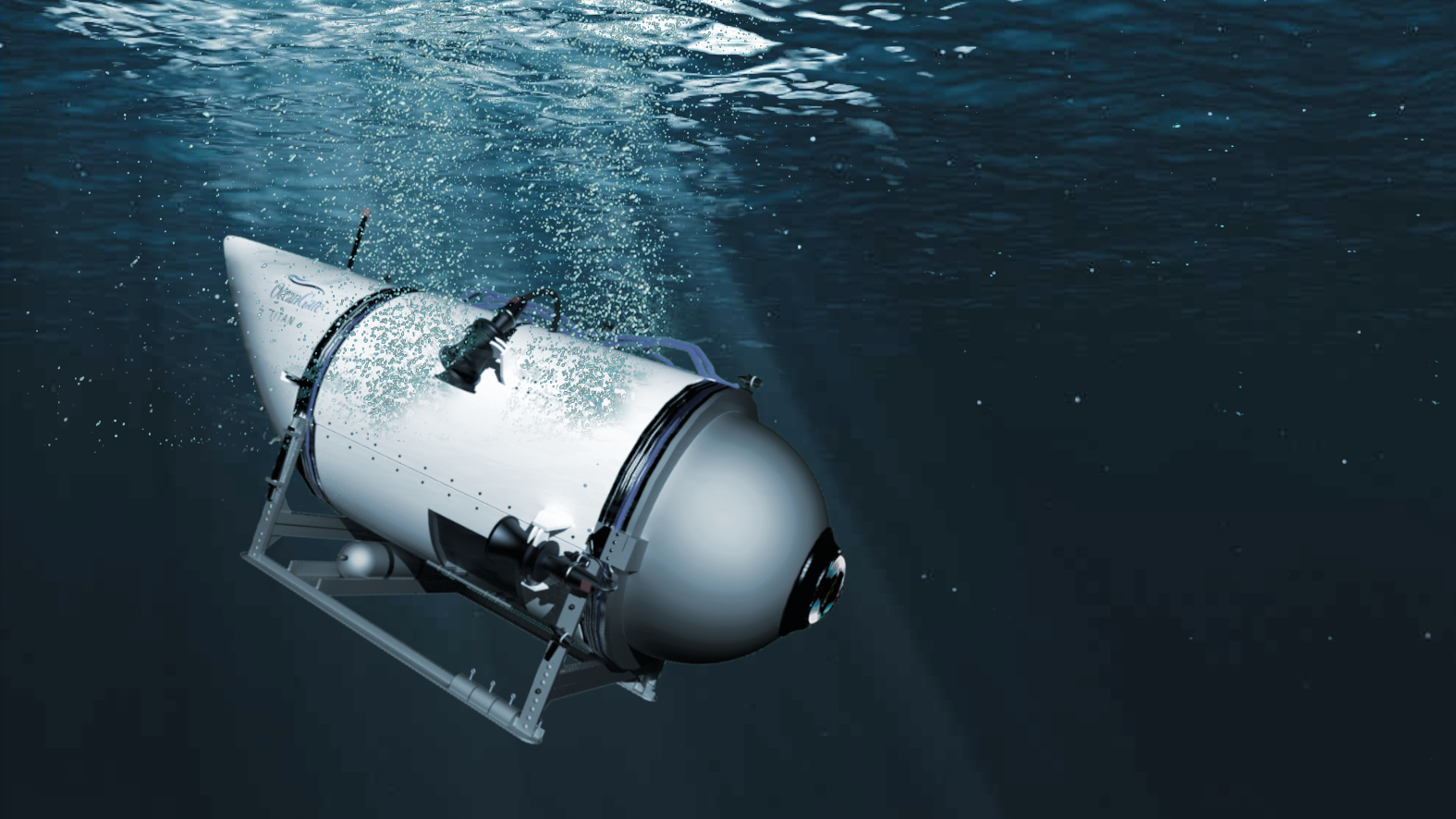

The implosion of the OceanGate Titan submersible 2 years ago, resulting in the deaths of all five people aboard, shocked the world. It was a tragedy that brought the inherent risks of deep-sea exploration into stark and sudden focus.

Now, an exclusive look into tens of thousands of internal OceanGate emails, documents, and photographs, along with interviews with former employees and third-party suppliers, reveals a disturbing inside story. These materials, provided exclusively to WIRED by anonymous sources, paint a picture of a company culture where safety concerns were repeatedly raised by engineers and experts but were often dismissed or ignored by OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush.

Stockton Rush, a former flight engineer and tech investor, cofounded OceanGate in 2009 with a vision for commercial and research trips to the ocean floor. He spoke with grand ambition, once telling a reporter, “I wanted to be the first person on Mars until I realized there was nothing there.” He saw the ocean as the true frontier, full of undiscovered life, stating, “My goal is to move the needle.”

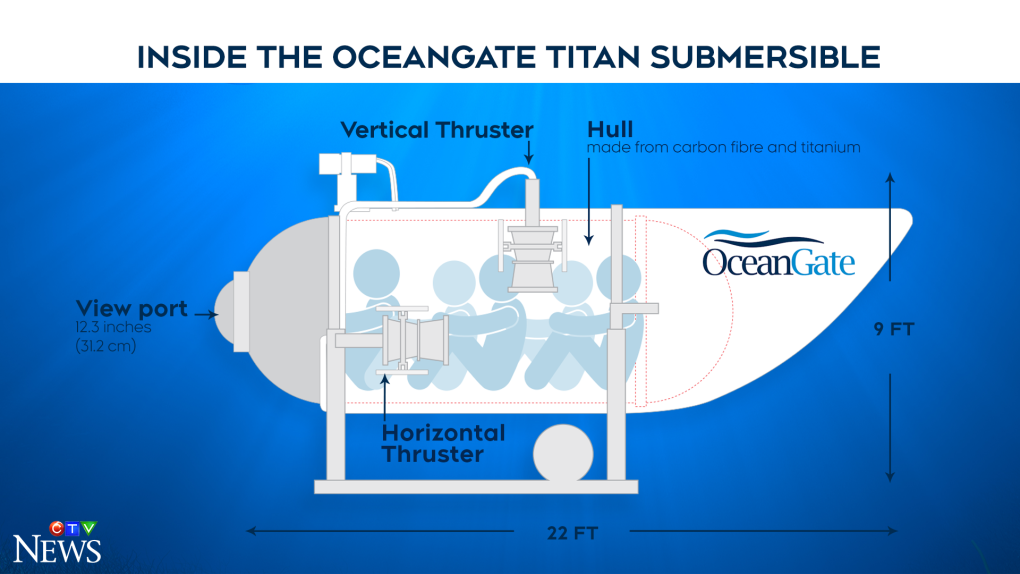

Initially, OceanGate used older, steel-hulled submersibles. But by 2013, Rush was pursuing a “revolutionary new manned submersible” he called Cyclops 2. Its key innovation was a lightweight carbon fiber hull designed to carry more passengers than traditional spherical cabins and dive much deeper than existing subs.

Rush’s ultimate goal for this new vessel, later renamed Titan, was to take paying customers on expeditions down to the wreck of the Titanic, lying 3,800 meters below the surface. At that depth, the pressure exerted by the ocean water is immense, approximately 6,500 pounds per square inch (psi), compared to 14.7 psi at sea level.

Testing the innovative design was crucial, and scale models were built for pressure testing. On the afternoon of July 7, 2016, a three-foot-long scale model of Cyclops 2 was being tested in a high-pressure facility at the University of Washington in Seattle. Water was pumped in, steadily increasing the pressure to mimic a dive.

At about the 73-minute mark, as the pressure gauge reached 6,500 psi – the equivalent of the Titanic’s depth – a sudden, violent roar erupted. The tank shuddered.

“I felt it in my body,” one OceanGate employee wrote in an email that night, describing the event. “The building rocked, and my ears rang for a long time.” He added, “Scared the shit out of everyone.”

The model had imploded at a depth equivalent to the Titanic, thousands of meters short of the safety margin OceanGate had designed for. In the high-stakes world of crewed submersibles, such a failure would typically send engineering teams back to the drawing board.

However, the exclusive documents and interviews reveal that Rush’s company did not take this step. Instead, within months of the implosion, OceanGate began building a full-scale Cyclops 2 based on the design of the imploded model. This full-sized vessel, the Titan, would go on to successfully reach the Titanic in 2021 and return for expeditions in 2022 before its fatal dive.

Carbon fiber is indeed a strong material, often stronger and lighter than titanium, making it attractive for engineering applications like aerospace. However, engineers Mark Negley and William Koch of Boeing Research & Technology, who produced a preliminary design report for OceanGate in October 2013, highlighted specific challenges for deep-sea applications.

They pointed out that carbon fiber can weaken progressively, sometimes unexpectedly, and the manufacturing process itself can introduce defects that compromise its strength. The risk of such defects increases with the number of layers used; Titan’s hull would ultimately have 660 layers.

To mitigate these risks, the Boeing engineers recommended rigorous quality assurance during manufacturing and subsequent ultrasound testing of the hull to detect defects or delaminations. This advice, detailed in their 70-page report, appears to have been a crucial early warning.

Early scale model testing of the carbon fiber hull components also showed worrying signs. In June 2015, a one-third scale model with carbon fiber end domes failed at pressures equivalent to around 3,000 meters. Although the cylinder portion performed better with solid aluminum ends, subsequent tests with new carbon fiber domes in March 2016 again resulted in implosion at 3,000 meters.

The fourth scale model test, the one that caused such alarm, reached 4,500 meters before imploding with aluminum caps. This test gave the design a meager 1.18 safety factor for dives to Titanic depths of 3,800 meters. James Cameron’s Deepsea Challenger had a safety factor of 1.36, and the submersible Alvin, which originally explored the Titanic, had 1.8 or higher.

Despite the clear indication that the model design failed below the target depth with inadequate safety margin, Rush wrote to shareholders that they would analyze data and run tests on a new cylinder through at least 1,000 cycles to confirm durability. However, former employees told WIRED that this replacement scale model was not made, and the planned tests never happened, partly because Rush trusted OceanGate’s computer models.

The final Titan design incorporated titanium end domes, a change from the tested carbon fiber domes. However, a former employee familiar with Rush’s decision said the CEO balked at the cost of commissioning models to test the interaction between the new materials, relying instead on analysis.

Another former employee reflected on this approach, saying, “The modeling says it’s OK. The analysis says it’s OK.” They added, “We build airplanes on the same type of analysis and then we go throw people in them.” However, experts note that carbon fiber behaves differently under external high pressure (like underwater) compared to internal high pressure (like an aircraft cabin), making underwater applications particularly sensitive.

Submersible experts outside OceanGate stressed the need for extensive testing on new designs. Adam Wright, who worked on a carbon-fiber sub for explorer Steve Fossett, stated, “We did at least 10 scale-model pressure hulls that we tested to destruction.” OceanGate, by contrast, tested its model hull to destruction only once and didn’t test the final configuration with titanium components.

Chase Hogoboom, president of Composite Energy Technologies, confirmed carbon fiber is a viable material but requires significant investment in engineering and manufacturing controls over many years. He noted, “It takes millions of dollars and many years, but it’s not rocket science. It’s just connecting the dots.” Despite this, OceanGate engineers later found the full-size Titan hull was too thick for portable ultrasound scanners, and a coating applied by the manufacturer further blocked signals. A former employee said Rush decided moving the sub to a lab for scanning was too expensive, resulting in no scans being made, contrary to the advice of Boeing and OceanGate engineers.

Further warnings arose concerning the Titan’s viewport. It was a new design by OceanGate’s director of engineering and manufactured by Hydrospace Group. Will Kohnen, Hydrospace CEO, expected thorough testing according to rigorous standards like those set by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, which involve testing multiple windows to destruction, cycling under pressure, and long-duration stress tests.

“The more innovative you get, the more testing you’ve got to do,” Kohnen said. He grew concerned in late 2017, telling WIRED, “Over a period of years, it was pretty obvious that OceanGate wasn’t going to do the testing.” Former OceanGate employees corroborated that the viewport was not tested to ASME standards.

In November 2017, as a final attempt, Kohnen emailed Rush offering a significant discount on a second viewport using a design certified to 4,000 meters, which could be swapped out quickly. Rush told him he wasn’t interested.

When Hydrospace delivered OceanGate’s viewport in December 2017, Kohnen rated it for only 650 meters – just one-sixth of the depth required for the Titanic. He also shared an analysis by an independent expert suggesting the design might fail after only a few dives to 4,000 meters. Despite this, OceanGate installed the viewport and advertised its first Titanic expedition scheduled for the following May.

Internal alarms were also sounding. In January 2018, David Lochridge, OceanGate’s director of marine operations, felt the Titan was unsafe. He sent Rush a quality-control report detailing 27 issues, including concerns about the carbon-fiber hull and questionable seals and components. Rush fired him the next day.

Lochridge later filed a whistleblower report, but Rush sued him, resulting in a settlement where Lochridge dropped his complaint and signed an NDA. The pattern of dismissing internal dissent was evident in OceanGate’s culture, where employees who questioned the rapid pace or decisions were sometimes dismissed as overly cautious or even fired.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(773x260:775x262)/titan-submersible-061724-1-82f74247e2ef4a2e80ddba10c72b6581.jpg)

The concerns extended across the industry. Will Kohnen remembers thinking, “We have a rogue element within the submersible industry,” fearing that a failure could negatively impact deep-sea exploration broadly. In March 2018, he drafted a letter, signed by over 30 crewed submersible experts, urging Rush to seek testing and certification from an accredited outside group like DNV or the American Bureau of Shipping.

While it has been widely reported that Rush dismissed such certification, the documents reveal OceanGate *did* pursue certification with DNV in 2017 until Rush learned the estimated cost of around $50,000. In an email, Rush wrote he had “grown tired of industry players who try to use a safety argument to stop innovation,” stating, “Since [starting] OceanGate we have heard the baseless cries of ‘you are going to kill someone’ way too often.”

Perhaps the most chilling warning came on March 30, 2018, in an email from Boeing’s Mark Negley, who had remained in contact with Rush. Having analyzed the Spencer Composites hull based on information from Rush, Negley did not mince words. He wrote, “We think you are at a high risk of a significant failure at or before you reach 4,000 meters. We do not think you have any safety margin.”

Negley urged Rush to “Be cautious and careful” and included a graph charting strain on the submersible against depth, which starkly displayed a skull and crossbones in the region below 4,000 meters, a vivid representation of the potential for catastrophic failure at Titanic depths.

Rush, however, seemed largely unfazed by these repeated warnings. His confidence was reportedly bolstered by a real-time health monitoring system designed by engineer Mike Furlotti, intended to detect the sounds of carbon fibers breaking under compression.

OceanGate’s theory was that the hull would be noisy initially but quiet down over repeated dives to the same depth, with increased noise indicating a need to surface immediately. However, industry experts were highly skeptical. Adam Wright noted the system’s uncertainty: “you just don’t know when the end point is,” adding, “You don’t know how many pops is too many, and it could be different for every vessel.”

Internal concerns about the system’s accuracy in tracking fiber breakage were also raised by an engineer in September 2017. While an outside consultant endorsed the system in 2018, he later expressed concern when Rush publicly claimed it could detect “micro-buckling” “way before it fails,” suggesting the CEO was overstating its capabilities.

The trove of documents and interviews lay bare a pattern of prioritizing ambition and cost savings over established safety protocols and expert warnings. From building a full-scale vessel based on a model that imploded thousands of meters short of its target depth to ignoring concerns about manufacturing defects, testing standards, viewports, and fundamental hull integrity, the path to the Titan’s tragic end appears, in retrospect, paved with opportunities to avoid disaster that were consistently bypassed.

Related posts:

The Titan Submersible Disaster Shocked the World. The Exclusive Inside Story Is More Disturbing Than Anyone Imagined

OceanGate adviser rips US rescue response — but firm faces claim it took 8 hours to raise alarm