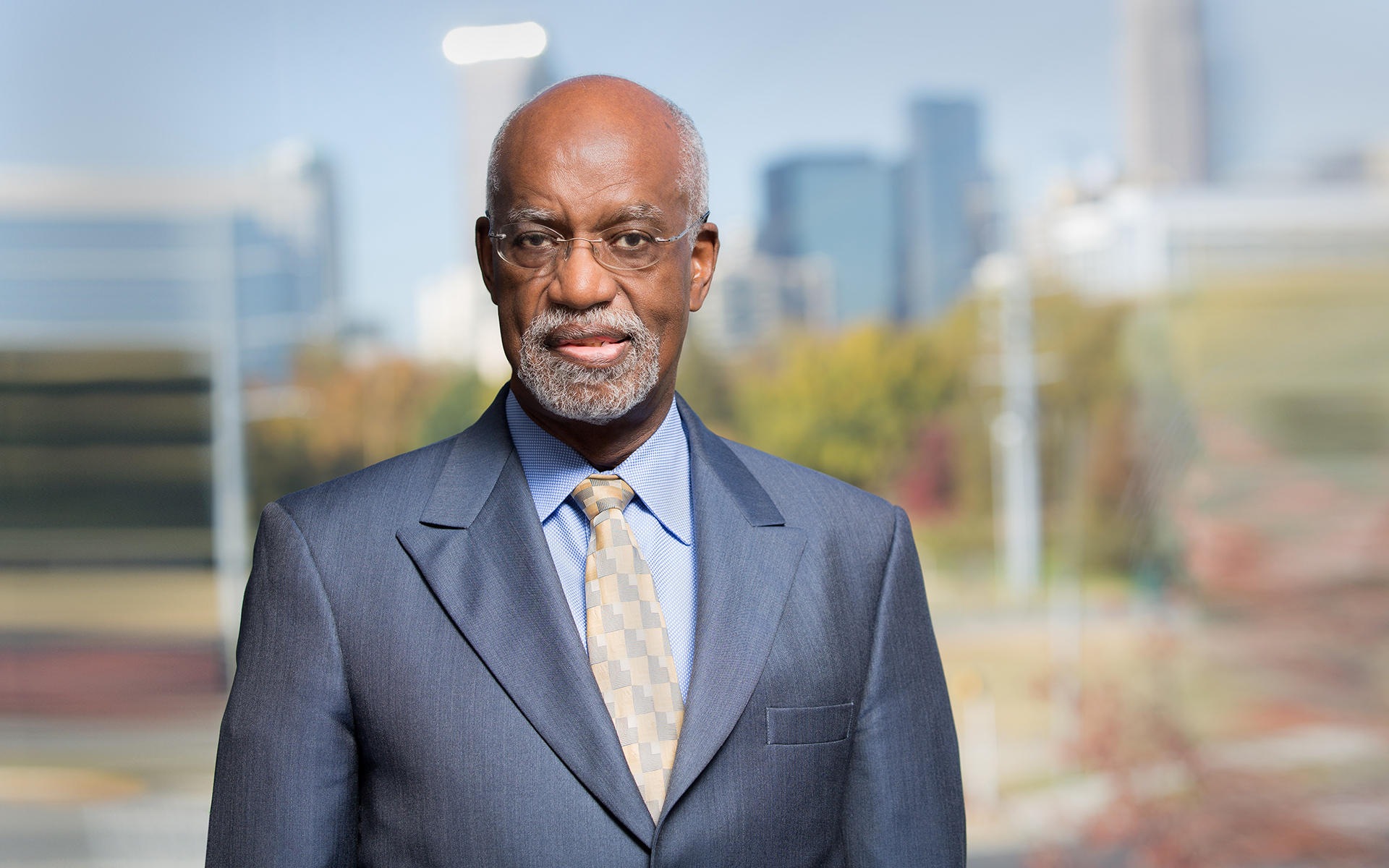

The world of civil rights advocacy lost a towering figure on July 21, 2025, with the passing of James E. Ferguson II in Charlotte, North Carolina. At 82 years old, Mr. Ferguson left behind a monumental legacy forged through decades of unwavering commitment to justice and equality in America. His death, caused by complications of Covid-19 and pneumonia, marks the end of an era defined by his instrumental role in some of the nation’s most pivotal legal battles.

A litigator whose work profoundly shaped the landscape of American society, Ferguson was central to persuading judges to desegregate schools, reverse wrongful convictions in civil rights cases, and spare sentenced prisoners the death penalty. He was more than a lawyer; he was, as he famously stated, part of “the legal arm of the civil rights movement in North Carolina.” His life story is a testament to the power of perseverance, courage, and a deep-seated belief in the possibility of a more just world.

From his early days fighting segregation in the Jim Crow South to his later years training lawyers in apartheid South Africa, Ferguson’s advocacy transcended geographical and legal boundaries. This article delves into the remarkable life and enduring contributions of James E. Ferguson II, examining the key cases, groundbreaking initiatives, and personal qualities that established him as one of the most prominent civil rights attorneys of his generation.

1. **Early Life and Student Activism in the Jim Crow South**James Edward Ferguson II was born on October 10, 1942, in Asheville, North Carolina, the youngest of seven children. His formative years were spent in a society rigidly structured by racial segregation, an experience he vividly described as facing a “wall of inferiorization” throughout his childhood. His father, James Jr., worked as a railway laborer, and his mother, Nina, was a housemaid, providing a modest upbringing in the heart of the Jim Crow South.

Even as a junior high school student, Ferguson’s inherent drive for justice began to manifest. He bravely fought through the political and racial turmoil of his time, initiating efforts to bring together all-Black and all-white schools for crucial discussions about race. This early activism laid the groundwork for a lifelong commitment to bridging racial divides and challenging entrenched segregation.

Before he even contemplated a legal career, Ferguson rallied fellow classmates in the Jim Crow South to actively integrate public facilities. He led courageous efforts to desegregate libraries and lunch counters across North Carolina, demonstrating a profound sense of civic responsibility and a clear vision for a more inclusive society. These actions showcased his capacity for leadership and his willingness to confront systemic injustice head-on, long before he earned his law degree.

His path to law was solidified during his high school senior year in 1960, as he became an advocate for civil rights in segregated Asheville. Consulting the city’s two Black lawyers for advice, he realized the immense power of the legal profession to effect societal change. “It hit me that that was a wonderful position to be in,” Mr. Ferguson recalled. He knew then that he “wanted to be in a position to bring about community change,” setting his future course.

Ferguson pursued higher education, earning a bachelor’s degree in English and history in 1964 from North Carolina College at Durham, now North Carolina Central University, where he served as student body president. He then received a juris doctor’s degree from Columbia University’s law school, attending on a scholarship. Upon graduation, he intentionally returned to the South, driven by a clear purpose: “to work for change.”

2. **Co-founding North Carolina’s First Interracial Law Firm**After graduating from Columbia Law School in 1967, James Ferguson II returned to North Carolina with a singular mission. He initially opened a one-man practice on East Trade Street in Charlotte in 1964. However, his vision for collaborative, impactful legal work quickly led him to form a groundbreaking partnership. He joined forces with another Black lawyer, Julius Chambers, and a white lawyer, Adam Stein, who is the father of North Carolina’s present governor, Josh Stein.

In 1967, this formidable trio launched what would become North Carolina’s first multiracial law firm, initially known as Chambers, Stein, Ferguson and Lanning. This establishment was not merely a business venture; it was a profound statement against the backdrop of a deeply segregated society. The firm itself stood as a living embodiment of the integration they tirelessly fought for within the legal system and broader community.

Adam Stein, one of the original partners, vividly recalled the firm’s humble beginnings. He remembered working out of what others might call a closet in Julius Chambers’ one-room uptown office, which they affectionately referred to as a “library.” In that confined space, with just enough room for a single table and two individuals, Stein and Ferguson forged a bond that transcended professional collaboration, evolving from strangers to colleagues to enduring friends.

“With anybody else that probably would have seemed terribly inconvenient,” Stein reflected, “But it was fine. We loved being together.” This shared experience of working closely in a small space fostered a deep camaraderie. Outside this “closet-office,” in a Charlotte and a world still largely segregated, their professional relationship blossomed into a familial connection, demonstrating a powerful personal integration that mirrored their legal advocacy.

Adam Stein, who is white, recounted how he, his wife, Jane, and their three children were “immediately taken into the world that Chambers and Ferguson inhabited” upon moving to Charlotte. Their entire “social life was the active African-American community,” a testament to the integrated personal and professional lives they built. Ferguson himself succinctly captured the firm’s essence, stating, “We weren’t practicing law in the abstract. We were the legal arm of the civil rights movement in North Carolina.”

3. **The Landmark Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education Case**One of the most consequential chapters in James Ferguson II’s career, and indeed in American civil rights history, was his pivotal involvement in *Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education*. This landmark case aimed to address the lingering effects of racial segregation in public schools, which persisted despite the 1954 *Brown v. Board of Education* ruling. While *Brown* declared segregation unconstitutional, schools in the late 1960s remained largely segregated due to housing patterns.

The genesis of the case came in 1969 when Darius and Vera Swann, along with nine other parents, filed a lawsuit against the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School Board. They contended that the board was violating the Constitution by failing to make proactive efforts to integrate schools, thereby denying their children an equal education. Julius Chambers, Ferguson’s law partner, served as the primary legal counsel, with Ferguson acting as his indispensable “right-hand man,” as recalled by Chambers’ son, Derrick.

The legal team successfully argued their case, leading to a monumental ruling by justices in *Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education* that mandated the school board create a busing plan to desegregate the school district. This decision was a direct challenge to the de facto segregation that characterized many American cities, demanding active measures to achieve racial balance in educational institutions. It fundamentally altered how school districts approached integration.

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the *Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools* decision unanimously. The justices declared that busing students, when implemented without harming their health or academic achievement, was an “appropriate and necessary means of implementing the integration” that had been mandated nearly two decades prior by *Brown v. Board of Education*. This affirmation by the nation’s highest court set a powerful precedent.

The *Swann* decision rapidly became a model for busing policies across the country, profoundly reshaping public education and the lives of millions of students. It was a career-defining case for Ferguson, one that truly changed schools and bus routes nationwide, cementing his legacy as a central figure in the fight for educational equality. His strategic insight and dedication were instrumental in achieving this sweeping legal victory.

4. **Enduring Threats and the Firebombing of His Law Office**The fight for civil rights, particularly in the deeply entrenched South, was fraught with danger, and James Ferguson II, along with his partners, faced severe retribution for their courageous advocacy. During the intense litigation of the *Swann* case, Chambers and Ferguson “endured protests, hate mail and firebombings of their houses and offices,” as previously reported by The Charlotte Observer. These threats were not abstract; they were direct and terrifying manifestations of the resistance they encountered.

One particularly harrowing incident involved the intentional torching of the modest law office that Mr. Ferguson shared with his partners. This act of arson, a deliberate attempt to intimidate and silence them, underscores the immense personal risk inherent in their work. While no one was charged in the arson, and mercifully, no injuries resulted, the impact on Ferguson was profound.

Ferguson himself later recounted that he never forgot the “helpless feeling of getting a call at 3 a.m. and then seeing the office aflame.” This traumatic experience, witnessing the physical destruction of their workplace—a symbol of their dedication to justice—served as a stark reminder of the volatile environment in which they operated. It was a moment that could have deterred lesser individuals, but for Ferguson, it only seemed to reinforce his resolve.

Despite such acts of violence and intimidation, Ferguson maintained an unyielding positive spirit. His son, Jay Ferguson, recalled, “In the most challenging moments that he had — when their office got burned down and Julius Chambers’ house got bombed — he always brought a positive spirit.” This resilience in the face of adversity highlights not only his personal strength but also his unwavering belief in the cause he championed. Such courage was essential in pushing forward the difficult and often dangerous work of civil rights.

5. **Continuing the Fight for Busing and School Integration**James Ferguson II’s commitment to school integration extended far beyond the initial *Swann* victory; he remained deeply involved in the ongoing battle for educational equity for decades. Even after the landmark 1971 Supreme Court decision, the implementation of busing and the broader goals of integration faced continuous challenges and evolving legal landscapes across the nation. Ferguson understood that securing a legal victory was often just the beginning of a sustained struggle.

His dedication was particularly evident in the late 1990s and early 2000s when the very principles established by *Swann* were re-challenged in the courts. Ferguson took on a leading role during this period, tirelessly advocating for the continued use of busing as a tool for desegregation. He represented Black parents who sought to uphold the foundational premise that school boards must actively work to integrate schools, even as some court decisions began to limit the scope of busing.

These later legal battles were critical in preserving the gains made decades earlier, though they did not always result in a full victory for his side. The challenge eventually concluded in April 2002 when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal from Black parents, effectively ending 32 years of court-mandated busing in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. Despite this outcome, Ferguson’s efforts ensured that the issue remained at the forefront of the national conversation, and that the fight for equitable education continued.

Sonya Pfeiffer, an attorney with whom Ferguson later worked, powerfully articulated the significance of his sustained efforts. “What he did for schools across the country was extraordinary,” she stated. She acknowledged the persistent challenges to achieving full integration and equality, adding, “Have we achieved integration and equality in any realm? The answer is no. But Fergie did what he could in the world that existed. It did make a difference.”

His unwavering advocacy in this complex and often disheartening struggle demonstrated his profound belief that true justice required continuous vigilance and commitment. Ferguson’s work on busing, from its inception to its contested later years, stands as a testament to his relentless pursuit of a society where educational opportunities are truly equitable for all children, regardless of race.

6. **Defending the Wilmington 10 and Overturning Wrongful Convictions**James Ferguson II’s dedication to justice was not confined to school desegregation; he also became a formidable advocate for those wrongfully accused and convicted, particularly in politically charged civil rights cases. Among his most prominent efforts in this arena was his defense of the Wilmington 10, a group of eight Black high school students, a young Black minister, and a white female social worker, who were unjustly entangled in a legal ordeal following racial turmoil.

These ten individuals were wrongfully convicted of arson and conspiracy in connection with school desegregation riots that erupted on North Carolina’s coast in 1971. The protests, fueled by racial tensions in the schools, escalated into rioting, tragically resulting in at least two deaths. Against a backdrop of widespread racial prejudice and intense public scrutiny, the convictions of the Wilmington 10 stood as a stark symbol of judicial unfairness.

Ferguson, working alongside Amnesty International and other dedicated lawyers, undertook the arduous task of challenging these unjust convictions. The defendants endured nearly a decade in prison for crimes they did not commit, highlighting the severe repercussions of a biased legal system. Ferguson’s team tirelessly pursued appeals and avenues for exoneration, determined to right the egregious wrong inflicted upon this group.

Through persistent legal efforts and public advocacy, all members of the Wilmington 10 were eventually released when the governor at the time commuted their sentences. However, it took another three decades for full justice to be rendered. In 2012, then-Governor Beverly Perdue officially pardoned them, a historic act that finally cleared their names and acknowledged the profound injustice they had suffered. The last of the group to be released, in 1979, was the Rev. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr., who later became executive director of the NAACP.

This victory for the Wilmington 10 underscored Ferguson’s steadfast commitment to due process and his unwavering belief in the innocence of those he defended. It was a powerful testament to his ability to navigate complex legal and political landscapes to achieve justice for the marginalized, demonstrating his role as a crucial safeguard against abuses within the criminal legal system.