James Grashow, an artist whose distinctive vision transformed the mundane into the monumental, died on September 15 at his home in Redding, Conn., at the age of 83. Known primarily for his ambitious sculptures crafted from corrugated cardboard, Mr. Grashow carved a unique niche in the art world, marrying a dark yet droll sensibility with an extraordinary ability to manipulate an ephemeral material. His career spanned decades, marked by a relentless pursuit of artistic expression across various mediums, always underpinned by a profound exploration of impermanence and the human condition.

The cause of death was pancreatic cancer, as confirmed by his wife, Lesley Grashow. Throughout his life, Mr. Grashow channeled “warring impulses toward the whimsical and the dark” into both two- and three-dimensional works, leaving an indelible mark on illustration, album art, and sculpture. His influence drew from a broad spectrum, from the intricate detail of 16th-century woodblock prints to the bold statements of 20th-century Pop Art, creating a body of work that was at once playful, haunting, and deeply meditative.

This in-depth look at James Grashow’s life and artistic contributions seeks to illuminate the multifaceted career of an artist who dared to build monuments from the disposable, culminating in a late-life masterwork in wood that contrasted sharply with his signature cardboard creations. We delve into the genesis of his unique aesthetic, his notable early commissions, and the conceptual underpinnings that made his temporary marvels resonate with enduring significance. His legacy is not merely in the objects he created, but in the challenging questions he posed about art, time, and existence itself.

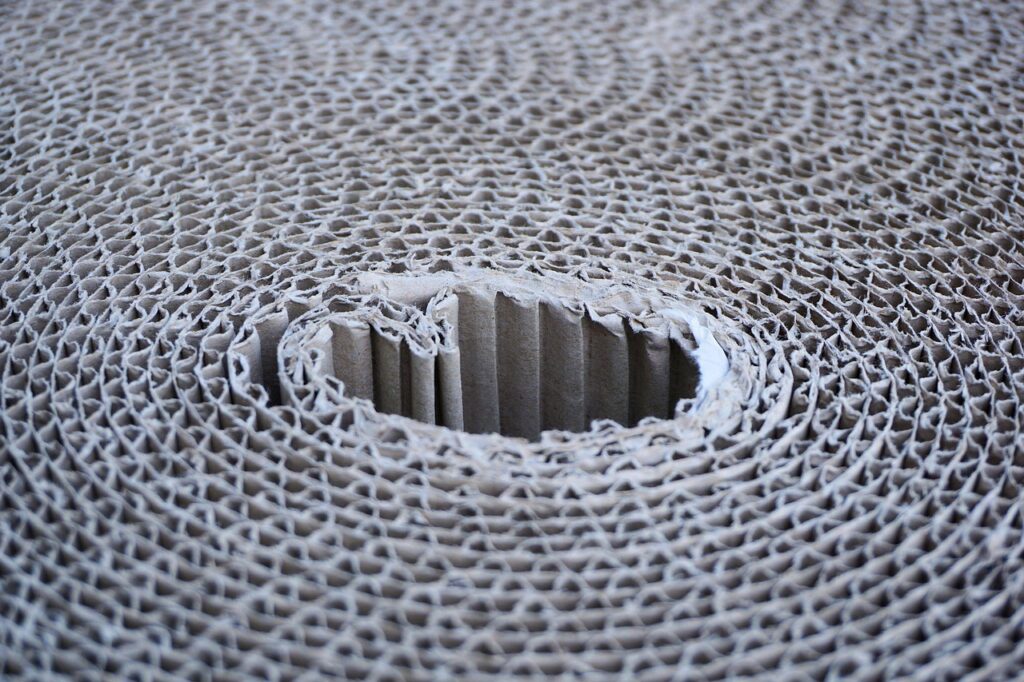

1. **The Signature Material: Corrugated Cardboard as a Medium**James Grashow was perhaps best known for his large, often fantastical installations, a body of work defined by his innovative use of an unexpected and inherently transient material: cheap, disposable corrugated cardboard. This everyday material, which he acquired “by the truckload in 4-by-8-foot sheets,” became the foundation for towering cities, elaborate fountains, and entire menageries, challenging traditional notions of sculpture typically associated with enduring materials like marble or bronze.

His choice of cardboard was not merely a pragmatic decision but a profound artistic statement. Unlike the permanence sought by classical sculptors, evanescence was, for Mr. Grashow, “the point.” He engaged with the full lifecycle of art, from creation to inevitable decay, exploring the temporal nature of existence through his deliberately impermanent works. This philosophy distinguished him from artists who focused solely on the initial act of creation, positioning him as a thoughtful chronicler of dissolution.

The use of cardboard allowed Mr. Grashow to construct monumental pieces that belied the humble origins of their components. This paradox — grandeur fashioned from the ordinary — was central to his aesthetic. It enabled him to craft structures that were both imposing and fragile, fantastical yet grounded in the reality of their eventual return to dust. His dedication to this material defined a significant portion of his career, yielding some of his most memorable and conceptually rich pieces.

2. **His Early Life and Artistic Genesis: Monsters, Goblins, and Cardboard Boxes**Born on January 16, 1942, in Brooklyn, James Bruce Grashow’s artistic journey began in a childhood steeped in imagination and tactile exploration. As the middle of three children to Edward Grashow, who owned an automobile antenna manufacturing company, and Estelle (Moscow) Grashow, young James found an early outlet for his creativity amidst the industrial detritus of his father’s business. He loved to assemble structures using the cardboard boxes readily available at the plant, foreshadowing his future mastery of the material.

Alongside this hands-on experimentation, Mr. Grashow was captivated by the act of drawing. He would often lose himself in sketching “fantastical images of monsters and goblins,” a predilection that would coalesce into the “dark yet droll vision” that characterized much of his later work. These childhood fascinations provided the bedrock for his unique blend of whimsy and gravity, a duality that would resonate throughout his career.

His academic journey, however, was initially fraught with challenges. Unbeknownst to him at the time, Mr. Grashow was dyslexic, a condition that caused him to struggle significantly as a student at Erasmus Hall High School in Flatbush. Art became his sanctuary and his escape, a realm where his vivid imagination and manual dexterity could flourish. After graduating in 1959, he enrolled at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where he studied painting. He recalled this period as transformative, stating, “As soon as I put my foot in the door, everything was fantastic.” His education continued with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1963, followed by a Fulbright scholarship to study painting in Florence, Italy, further broadening his artistic horizons.

3. **A Duality in Vision: Whimsical and Dark Impulses**A defining characteristic of James Grashow’s oeuvre was his remarkable ability to channel “warring impulses toward the whimsical and the dark” into his diverse artistic expressions. This duality, described as a “dark yet droll vision” that “formed in childhood,” was not a contradiction but a sophisticated interplay, allowing his works to simultaneously entertain and provoke deeper contemplation. His art often possessed a playful surface that belied a profound underlying commentary on mortality and existence.

This intricate balance was evident across his chosen mediums. In his sculptures, he created “anthropomorphic, devilishly smirking skyscrapers” for “The City” and a grandiose yet deliberately decaying cardboard rendition of the Trevi Fountain. These works presented familiar forms through a distorted, often humorous lens, yet they carried an unsettling undercurrent, hinting at the fragility and inevitable decline inherent in all things. The drollness served as an accessible entry point to themes that were inherently somber.

Similarly, his two-dimensional works, particularly his wood engravings for various publications, were frequently described as “brooding and phantasmagorical.” They exhibited a rich imagination populated by creatures and scenarios that veered into the macabre, yet always with a distinctive style that prevented them from being merely frightening. Mr. Grashow masterfully navigated this emotional spectrum, inviting viewers to engage with his creations on multiple levels, appreciating both their visual wit and their existential weight.

4. **Editorial Illustrations: Brooding and Phantasmagorical Wood Engravings**Beyond his sculptural achievements, James Grashow established a distinguished career as an award-winning editorial illustrator, contributing his unique vision to prominent publications such as The New York Times, Esquire, and Time. In this realm, his primary medium was wood engraving, through which he created striking images that were frequently characterized as “brooding and phantasmagorical.” These illustrations brought a distinct artistic voice to news and commentary, complementing the textual narratives with visually rich and often thought-provoking imagery.

His wood engravings often captured complex ideas with a singular, impactful image, demonstrating a profound understanding of visual storytelling. They were not merely decorative but served as incisive interpretations of the articles they accompanied, infusing them with a sense of depth and a unique artistic perspective. The meticulous detail inherent in wood engraving allowed him to render intricate scenes and figures that conveyed both narrative and emotional resonance, perfectly aligning with his nuanced vision.

A notable example of his editorial work is his illustration for a 1977 Opinion article in The Times concerning the effects of urban sprawl on suburban areas. For this piece, Mr. Grashow “conjured a massive, wild-eyed dragon made from jagged skyscrapers lurching toward a leafy town.” This image powerfully encapsulated the encroaching, destructive force of development, using his signature blend of the fantastical and the darkly insightful to comment on a pressing social issue. Such works underscored his capacity to translate abstract concepts into compelling visual metaphors, solidifying his reputation as a master illustrator.

5. **Iconic Album Covers: Jethro Tull and The Yardbirds**James Grashow’s distinctive artistic style also found a prominent platform in the world of music, where he created memorable cover art for several album releases. These commissions brought his unique blend of intricate detail, whimsical forms, and underlying darkness to a wide, popular audience, making his work instantly recognizable to music enthusiasts and art lovers alike. The album covers served as miniature galleries for his imaginative creations, showcasing his ability to craft compelling visuals that complemented the sonic landscapes within.

Among his most famous contributions were the covers for two iconic albums of the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 1969, his art graced the cover of Jethro Tull’s seminal album, “Stand Up.” The artwork for this album captured the band’s folk-rock sensibility with a visual flair that spoke to the era’s artistic innovations. This particular commission allowed Mr. Grashow to present his intricate and somewhat surreal imagery to a global audience, contributing to the album’s overall artistic identity.

Two years later, in 1971, Mr. Grashow’s art was featured on the cover of the Yardbirds’ “Live Yardbirds: Featuring Jimmy Page.” This cover, like his work for Jethro Tull, utilized his distinctive style to create a visually arresting image that resonated with the album’s content. These album covers not only stand as significant pieces within his extensive portfolio but also underscore the breadth of his influence, demonstrating how his artistic versatility allowed him to transcend traditional gallery spaces and reach diverse cultural spheres, embedding his aesthetic into popular consciousness.

6. **The Monumental “The City”: Anthropomorphic Skyscrapers**Among James Grashow’s most striking early large-scale installations was “The City,” a monumental work from 1980 that powerfully articulated his signature blend of whimsy, darkness, and anthropomorphism. Crafted from a combination of “cardboard, plywood and fabric,” this ambitious piece stood at an imposing “13-foot-tall.” Its sheer scale immediately commanded attention, drawing viewers into its intricately detailed, yet unsettling, urban landscape.

“The City” was not merely a collection of buildings; it was an “aggregation of anthropomorphic, devilishly smirking skyscrapers.” Each structure possessed a distinct personality, imbued with facial features and postures that suggested sentience and a mischievous, almost sinister, awareness. This personification of inanimate objects was a hallmark of Grashow’s imaginative approach, allowing him to infuse his architectural forms with a narrative quality that transcended mere representation.

The installation managed to be “at once cartoonish and haunting,” a perfect embodiment of his recurring dualistic vision. The playful, almost caricature-like appearance of the skyscrapers invited initial amusement, yet their “devilishly smirking” expressions and towering presence evoked an underlying sense of unease. “The City” served as an early and vivid demonstration of Mr. Grashow’s capacity to use the humble medium of cardboard to create immersive, thought-provoking environments that explored the complex relationship between the built world and human emotion, paving the way for even grander, more philosophical works to come.

7. **The Great Monkey Project: A Menagerie of Impermanence**Continuing his exploration of large-scale installations crafted from corrugated cardboard, James Grashow undertook “The Great Monkey Project” in 2006. This ambitious endeavor brought forth a whimsical yet poignant spectacle, comprising one hundred life-size cardboard monkeys. These meticulously fashioned simians were depicted dangling from vines, creating an immersive environment that invited contemplation on both the playful and ephemeral nature of existence.

“The Great Monkey Project” underscored Mr. Grashow’s enduring fascination with creating expansive narratives from an unconventional medium. Each monkey, though constructed from disposable material, possessed a distinct character, contributing to a collective sense of vitality and movement. The sheer volume of the installation, with a hundred individual figures, magnified the impact of his signature material choice, elevating the ordinary into the extraordinary.

In this work, the implicit impermanence of cardboard served as a quiet commentary on cycles of life and decay. The playful imagery of monkeys in motion contrasted with the inherent fragility of their construction, subtly reinforcing Mr. Grashow’s recurring artistic philosophy. It represented another significant milestone in his career, demonstrating his unwavering commitment to challenging perceptions of art’s longevity and material value.

8. **”Corrugated Fountain”: A Meditative Exploration of Dissolution**Perhaps Mr. Grashow’s most iconic and philosophically charged work in cardboard was his monumental “Corrugated Fountain,” a packing-box reinterpretation of Rome’s famous Trevi Fountain. Unlike its classical inspirations, which were built for enduring permanence, Mr. Grashow’s version was intentionally designed for dissolution. This grand-scale piece occupied an area of roughly 20 by 30 feet and stood approximately 12 feet tall, featuring a proud, if cardboard, rendition of Oceanus, the Greek deity of the waters, at its center.

“Evanescence was the point,” Mr. Grashow stated, articulating the core principle behind this ambitious project. He exhibited the waterless fountain in four museums, starting in 2010, allowing audiences to engage with its intricate details before its predetermined fate. His artistic process extended beyond mere creation; it encompassed the work’s inevitable return to its constituent elements, a concept he elaborated on by saying, “All artists talk about process… But the process that they talk about is always from beginning to finish, and nobody really talks about full-term process — to the end, to the destruction, to the dissolution of a piece.”

For its final exhibition at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Mr. Grashow deliberately moved the “Corrugated Fountain” outside, exposing it to the elements. Within weeks, the relentless rain transformed the monumental cardboard structure into a “mushy tangle,” mirroring his artistic vision of ruins akin to the ancient statue in Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias.” This act of controlled destruction was a profound artistic statement, highlighting that, like the Afghan Buddhas and the World Trade Center, “everything has its time,” a stark reminder of the transient nature of even the grandest human endeavors.

9. **Philosophy of Impermanence: Echoes of Auto-Destructive Art**James Grashow’s consistent engagement with impermanence as a central tenet of his art positioned him uniquely within contemporary sculpture. His philosophy, deeply embedded in the choice of corrugated cardboard as his primary medium, deliberately challenged the traditional art historical pursuit of lasting physical monuments. For Mr. Grashow, the process of creation was inextricably linked to the process of decay, making dissolution an integral, rather than incidental, part of the artwork’s existence.

This approach bore some philosophical resemblance to the mid-20th-century artist Gustav Metzger’s theories of auto-destructive art, which advocated for works designed to self-destruct. However, Mr. Grashow’s vision was notably more meditative than violent. While Metzger’s works often aimed to provoke through their aggressive dismantling, Grashow’s creations invited a more reflective contemplation on the passage of time and the universal truth of decay. His was a gentle, almost elegaic acknowledgment of the inevitable.

His declaration that “Everything dissolves in eternity” encapsulates this core belief, asserting that all physical forms, regardless of their initial material or artistic intent, are subject to the forces of time and nature. This perspective transformed his art from mere objects into profound meditations on the temporal nature of existence itself, offering viewers a unique opportunity to witness the full cycle of artistic life, from genesis to ultimate, poetic dissolution.

10. **Personal Themes of Mortality: “The Basic One Was Croaking”**Underlying the whimsical surfaces and grand scales of James Grashow’s creations was a deeply personal and recurrent engagement with the theme of mortality. He openly acknowledged that many of his works, including the “Corrugated Fountain,” evoked themes “based in my own emotional problems.” This candid insight reveals a profound connection between his internal anxieties and his artistic output, lending an additional layer of pathos and sincerity to his conceptually rich installations.

In a 1986 interview for the book “Innovators of American Illustration,” Mr. Grashow stated with striking directness, “The basic one was croaking. Death has been the single prime force in everything that I’ve ever done.” This declaration provides a crucial interpretive lens for understanding his entire oeuvre, suggesting that his artistic journey was, in essence, a prolonged rumination on his own impermanence and the universal human confrontation with finitude. The duality of his vision—the whimsical alongside the dark—can thus be seen as an artistic coping mechanism, allowing him to approach a weighty subject with a distinctive, droll sensibility.

His deliberate creation of art destined for decay, as exemplified by the “Corrugated Fountain,” was not merely an academic exercise in auto-destructive theory. It was a tangible, visceral manifestation of his acceptance of death as an inherent part of life’s process. Through his impermanent monuments, Mr. Grashow invited audiences to share in his contemplative journey, transforming a deeply personal fear into a universally resonant artistic statement about the beauty and tragedy of transient existence.

11. **Late-Career Shift: “The Cathedral” and the Enduring Quality of Woodcarving**In his late 70s, James Grashow embarked on a significant artistic pivot, turning from the ephemeral medium of cardboard to the enduring quality of woodcarving. This shift culminated in what he considered his “tour de force,” a monumental eight-foot-tall basswood sculpture titled “The Cathedral.” Completed in June 2024 after four years of intensive labor, this piece marked a profound departure in material, signaling a late-life exploration of permanence that stood in stark contrast to his earlier philosophical commitments.

“The Cathedral” depicts Jesus wearing a crown of thorns, carrying not a traditional cross but a Gothic cathedral on his back, with “snarling demons dancing at his feet.” Although Mr. Grashow was Jewish, he chose Jesus as his subject, explaining that the Christian savior symbolized for him “endurance through faith, even with death looming.” This choice, stemming from a commission that was largely “all my idea,” reflected an 82-year-old artist’s deeply personal quest to “figure out how to keep his faith alive in an increasingly chaotic world.” The intricate detail and robust material of this work underscore a desire to create something that would indeed “last for the long haul.”

The arduous four-year process of creating “The Cathedral” provided Mr. Grashow with a final, extended period to ruminate on his own impending mortality. In the 2025 documentary “Jimmy and the Demons,” which chronicles this endeavor, he shared poignant reflections: “I feel like I’m running in front of a wave for three years,” he remarked. “And I never thought I’d get here. I never thought it would be finished.” He concluded with a somber recognition of time’s relentless advance: “And now I feel the wave catching up to me. It’s a big wave, and I’m a little, little man.” This final, enduring masterwork served as both a testament to his artistic prowess and a deeply personal reckoning with his own impermanence.

12. **Enduring Legacy: Teaching, Exhibitions, and Documentary Films**James Grashow’s influence extended far beyond the confines of his studio, cementing a multifaceted legacy through his dedication to teaching, extensive museum exhibitions, and the indelible mark left by documentary films about his work. A longtime educator, he shared his expertise and unique artistic philosophy with generations of students at institutions such as the Pratt Institute, fostering a new cohort of artists capable of seeing grandeur in the unconventional.

His works were widely recognized and celebrated within the art world, featured in dozens of galleries and museums throughout his career. Prestigious venues such as the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Armory Show in New York prominently displayed his sculptures and woodcuts, affirming his status as a significant contemporary artist. These exhibitions ensured that his distinctive vision, whether manifested in an ephemeral cardboard city or a brooding wood engraving, reached a broad and appreciative audience.

The profound philosophical depth and visual spectacle of his major projects also captured the attention of filmmakers. He became the subject of two notable documentaries: “The Cardboard Bernini” (2012) meticulously chronicled the creation, exhibition, anticipated decay, and ultimate destruction of his “Corrugated Fountain,” offering an intimate look into his theories of impermanence. More recently, “Jimmy and the Demons” (2025), directed by Cindy Meehl and premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, explored his late-life pivot to woodcarving with “The Cathedral.” These films serve as invaluable chronicles, preserving his artistic journey and philosophical insights for future generations, ensuring that his unique voice continues to resonate even after his passing.

James Grashow’s passing marks the end of an extraordinary artistic journey, yet his legacy will undoubtedly endure. His unique ability to infuse humble materials with profound philosophical inquiry, to navigate the space between the whimsical and the melancholic, and to challenge the very notion of artistic permanence, cemented his place as an innovator. From the fantastical monsters of his childhood drawings to the enduring solace found in his final wooden masterwork, Mr. Grashow invited us to see art not just as an object, but as a dynamic reflection of life’s intricate dance between creation and dissolution. His contributions remind us that true artistic impact lies not solely in what is built to last, but also in what courageously embraces its own inevitable end, leaving behind questions that resonate with eternal significance.