Embark on a captivating exploration into the heart of the Russian language, a vibrant and dynamic tongue that weaves through centuries of history, culture, and innovation. Far more than just a means of communication, Russian stands as a testament to linguistic resilience and global interconnectedness. Its vast tapestry of sounds and structures reflects a rich heritage, connecting millions across continents.

At its very core, Russian is an East Slavic language, tracing its lineage back through the Balto-Slavic branch to the ancient Indo-European family. It proudly stands as one of four extant East Slavic languages, inheriting its foundational essence from Old East Slavic, which also gave rise to modern Belarusian and Ukrainian. The linguistic journey of Russian has been one of fascinating interactions, showing notable lexical similarities with Bulgarian, largely due to a shared influence from Church Slavonic. Yet, it also absorbed a wealth of vocabulary and literary styles from a diverse array of Western and Central European languages, including Greek, Latin, Polish, Dutch, German, French, Italian, and English. Intriguingly, it also drew from the languages of the south and east, such as Uralic, Turkic, Persian, Arabic, and Hebrew, demonstrating its permeable and adaptive nature. For native English speakers, mastering this complex yet rewarding language requires dedication, with the Defense Language Institute classifying it as a level III language, requiring approximately 1,100 hours of immersion instruction to achieve intermediate fluency.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/question-do-you-speak-russian--written-in-russian-506675034-2d406dc9ee6e4708844d21cf0e267c6d.jpg)

With over 253 million total speakers worldwide between 2012 and 2023, Russian is a true linguistic colossus. This includes a robust 145 million native (L1) speakers as of 2020–2023. It proudly holds the distinction of being the most spoken native language in Europe, the most spoken Slavic language, and the most geographically widespread language of Eurasia. Globally, it ranks as the world’s seventh-most spoken language by native speakers and the ninth-most spoken by total speakers. Its international prominence extends into vital global arenas, being one of the two official languages aboard the International Space Station and one of the six official languages of the United Nations. Furthermore, it holds a significant digital footprint, standing as the fourth most widely used language on the Internet, underscoring its contemporary relevance.

Russian finds official status in several UN member states, including the Russian Federation, Belarus (co-official), Kazakhstan (co-official), Kyrgyzstan (co-official), and Tajikistan, where it serves as an inter-ethnic language. Its influence extends to a regional level, co-officially recognized in Moldova’s Gagauzia and Left Bank of the Dniester, and Ukraine’s Autonomous Republic of Crimea. Even partially recognized states such as Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria embrace it as a co-official language. Beyond these, Russian is recognized as a minority language in countries like Romania, Armenia, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Moldova, Ukraine, and China, painting a vivid picture of its widespread acceptance and utility across diverse geopolitical landscapes.

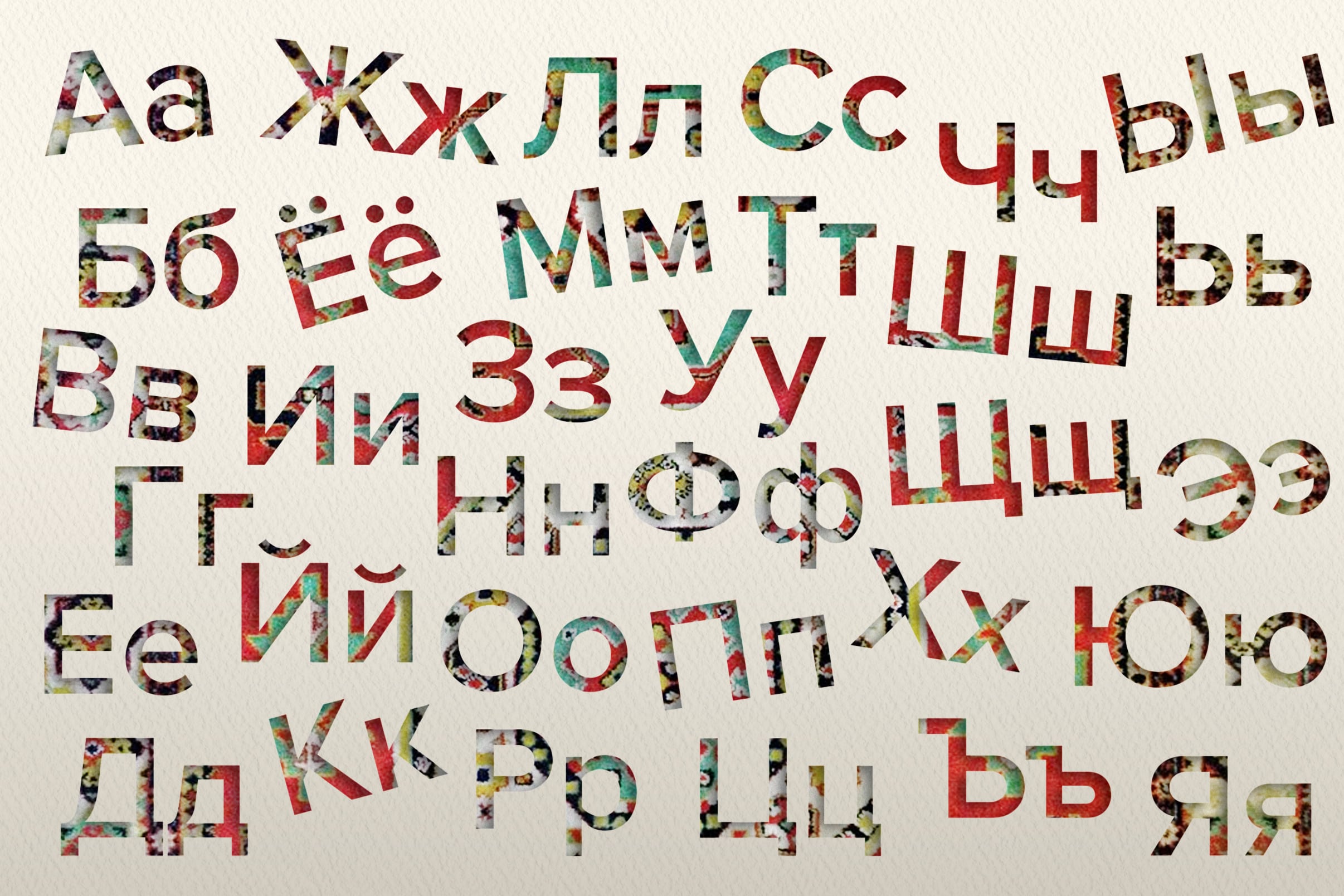

The elegance of Russian finds its expression in the Cyrillic script, specifically the Russian alphabet. This script is uniquely designed to capture the language’s distinctive feature: the nuanced difference between consonant phonemes with and without palatal secondary articulation, famously known as “soft” and “hard” sounds. This distinction is often conveyed not by altering the consonant itself, but by modifying the subsequent vowel, a subtle yet profound characteristic. Another important aspect is the reduction of unstressed vowels, adding to the phonetic beauty of the language. While stress is often unpredictable and not typically indicated in orthography, an optional acute accent can be employed to clarify meaning between homographic words, such as замо́к (‘lock’) and за́мок (‘castle’), or to guide the pronunciation of uncommon words and proper nouns, ensuring clarity and precision in communication.

The evolution of Russian orthography is a story of deliberate refinement. The early Cyrillic alphabet, adapted from Old Church Slavonic, underwent its first significant reform between 1708 and 1710, with the last major overhaul occurring in 1917–1918. The Russian alphabet today comprises 33 letters, each with a typical sound value. Beyond these, older letters like ⟨ѣ⟩, ⟨і⟩, ⟨ѵ⟩, ⟨ѳ⟩, ⟨ѫ⟩, ⟨ѭ⟩, ⟨ѧ⟩, and ⟨ѩ⟩ have been abandoned over time, their sounds merging into modern equivalents. The use of an optional acute accent to mark stress is a vital tool, not only for distinguishing homographs but also for indicating the proper pronunciation of less common words and proper nouns, and even to highlight the stressed word in a sentence, adding a layer of precision to written communication. For children and learners, these stress marks are mandatory in dictionaries and educational books, facilitating their grasp of this intricate phonetic system.

Delving deeper into its auditory landscape, Russian phonology reveals a remarkably complex syllable structure, allowing for both initial and final consonant clusters of up to four consecutive sounds. Its intricate dance of consonants is particularly notable for its distinction based on palatalization, where the center of the tongue rises during and after articulation, creating distinct “soft” and “hard” counterparts for almost every consonant. The sounds /t, d, ts, s, z, n, rʲ/ are dental, pronounced with the tongue tip against the teeth. Some linguists also point to the velarization of “plain” consonants, especially a labial before a hard vowel, adding further richness to its sound profile. Russian boasts five or six vowels in stressed syllables (/i, u, e, o, a/, and sometimes /ɨ/), which elegantly merge to a smaller set in unstressed positions, demonstrating a sophisticated system of vowel reduction and allophonic variation that contributes to the language’s unique melodic quality.

The grammatical architecture of Russian is a fascinating study in its own right, having meticulously preserved an Indo-European synthetic-inflectional structure. This means that grammatical relationships are primarily expressed through changes in word endings rather than through separate words or fixed word order. While considerable leveling has occurred over centuries, its highly fusional morphology allows for a single ending to convey multiple grammatical categories simultaneously. This linguistic characteristic contributes to a flexible syntax for the literary language, offering a remarkable degree of expressiveness and stylistic versatility.

The journey toward a standardized Russian language is a tale intertwined with political and cultural shifts. Feudal divisions and conflicts, particularly during the Mongol rule, created significant obstacles between Russian principalities, reinforcing dialectal differences and impeding the emergence of a unified national tongue. However, with the formation of a unified and centralized Russian state in the 15th and 16th centuries, a shared political, economic, and cultural space gradually re-emerged, igniting an urgent need for a common standard language. The initial impetus for standardization sprang from the government bureaucracy, which acutely felt the practical problem of lacking a reliable communication tool in administrative, legal, and judicial affairs. Early attempts at standardization during the 15th to 17th centuries were thus based on the Moscow official or chancery language, setting a precedent for future linguistic policy. Since then, the trend has consistently been toward standardization, aiming to reduce dialectical barriers among ethnic Russians and to expand the use of Russian alongside, or even in favor of, other languages.

The current standard form, known as the modern Russian literary language or Contemporary Standard Russian, began to flourish at the start of the 18th century. This linguistic evolution coincided with the ambitious modernization reforms spearheaded by Peter the Great, drawing its essence from the Moscow (Middle or Central Russian) dialect substratum, gracefully influenced by the earlier Russian chancery language. It is noteworthy that while the Moscow dialect originally had a northern dialectal base, its ascendancy as the center of a unified state attracted speakers from southern dialects, culminating in the formation of a transitional dialect group. Before the Bolshevik Revolution, the spoken form of Russian embraced by the nobility and urban bourgeoisie largely defined the standard. In stark contrast, the vast majority of the population, the Russian peasants, continued to speak in their diverse dialects. Sadly, these peasant dialects were rarely studied systematically by philologists, often regarded merely as sources of folklore or objects of curiosity. As noted Russian dialectologist Nikolai Karinsky lamented, scholars of Russian dialects primarily focused on phonetics and morphology, with almost no studies on lexical material or syntax. After 1917, Marxist linguists dismissed the multiplicity of peasant dialects, viewing them as relics of a rapidly disappearing past, unworthy of scholarly attention. They believed that as peasants transitioned to factories, their dialects would level out, giving way to a “general language of the working class,” driven by the unifying forces of industrialization and capitalism, which tended to create a general urban language for society.

Exploring the geographical distribution of Russian speakers paints a truly fascinating picture of a language that transcends borders, deeply woven into the fabric of numerous nations. In 2010, the global count of Russian speakers reached an astonishing 259.8 million. Within Russia itself, 137.5 million people spoke Russian. The CIS and Baltic countries accounted for 93.7 million, with significant populations in Eastern Europe (12.9 million), Western Europe (7.3 million), Asia (2.7 million), the Middle East and North Africa (1.3 million), Sub-Saharan Africa (0.1 million), and Latin America (0.2 million). North America, Australia, and New Zealand together contributed 4.1 million speakers. This impressive global presence firmly establishes Russian as the world’s seventh-largest language by total number of speakers, following English, Mandarin, Hindi-Urdu, Spanish, French, Arabic, and Portuguese.

Across Europe, Russian continues to hold sway, albeit with varying official statuses and societal dynamics. In Belarus, Russian stands as a second state language alongside Belarusian, as enshrined in its constitution. In 2006, a remarkable 77% of the population reported fluency in Russian, and 67% used it as their main language for daily interactions. The 2019 Belarusian census further illuminated this linguistic landscape: while 54.1% named Belarusian as their native tongue, a significant 71.4% stated they speak Russian at home, including a substantial majority of ethnic Belarusians (61.4%), Russians (97.2%), Ukrainians (89.0%), Poles (52.4%), and Jews (96.6%), underscoring its prevailing use in everyday life.

In Estonia, Russian is officially considered a foreign language, yet it is spoken by 29.6% of the population, according to a 2011 estimate. The issue of school education in Russian remains a highly contentious point in Estonian politics, leading to a significant parliamentary decision in 2022 to transition all Russian-language schools and kindergartens to Estonian-only instruction, beginning in the 2024–2025 school year. Similarly, in Latvia, Russian is also designated a foreign language. Despite this, 55% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, with 26% using it as their main language. A 2012 constitutional referendum to adopt Russian as a second official language was decisively rejected by 74.8% of voters. Recent legislative changes have further reinforced Latvian as the primary language, with instruction in Russian being gradually discontinued in private colleges, universities, and public high schools since 2019. In a pivotal move on September 29, 2022, the Saeima passed amendments for all schools and kindergartens to transition to Latvian-only education from 2025. This was followed by the approval of The National Security Concept on September 28, 2023, which mandates all content from Latvian public media to be exclusively in Latvian or a language “belonging to the European cultural space” from January 1, 2026, leading to the cessation of state financing for Russian-language content and the likely closure of Russian broadcasts.

Lithuania presents a different scenario; Russian holds no official or legal status, though a large segment of the population, particularly older generations, can speak it as a foreign language. However, English has remarkably replaced Russian as the lingua franca, with approximately 80% of young people speaking English as their first foreign language. Lithuania also has a comparatively smaller Russian-speaking minority, at 5.0% in 2008, with 7.2% citing Russian as their native language in the 2011 census. In Moldova, Russian was historically considered the language of interethnic communication under a Soviet-era law. However, on January 21, 2021, the Constitutional Court of Moldova declared this law unconstitutional, stripping Russian of this status. In 2006, 50% of the population was fluent in Russian, and 19% used it as their main language. The 2014 Moldovan census showed Russians accounting for 4.1% of the population, with 9.4% declaring Russian as their native language and 14.5% using it regularly.

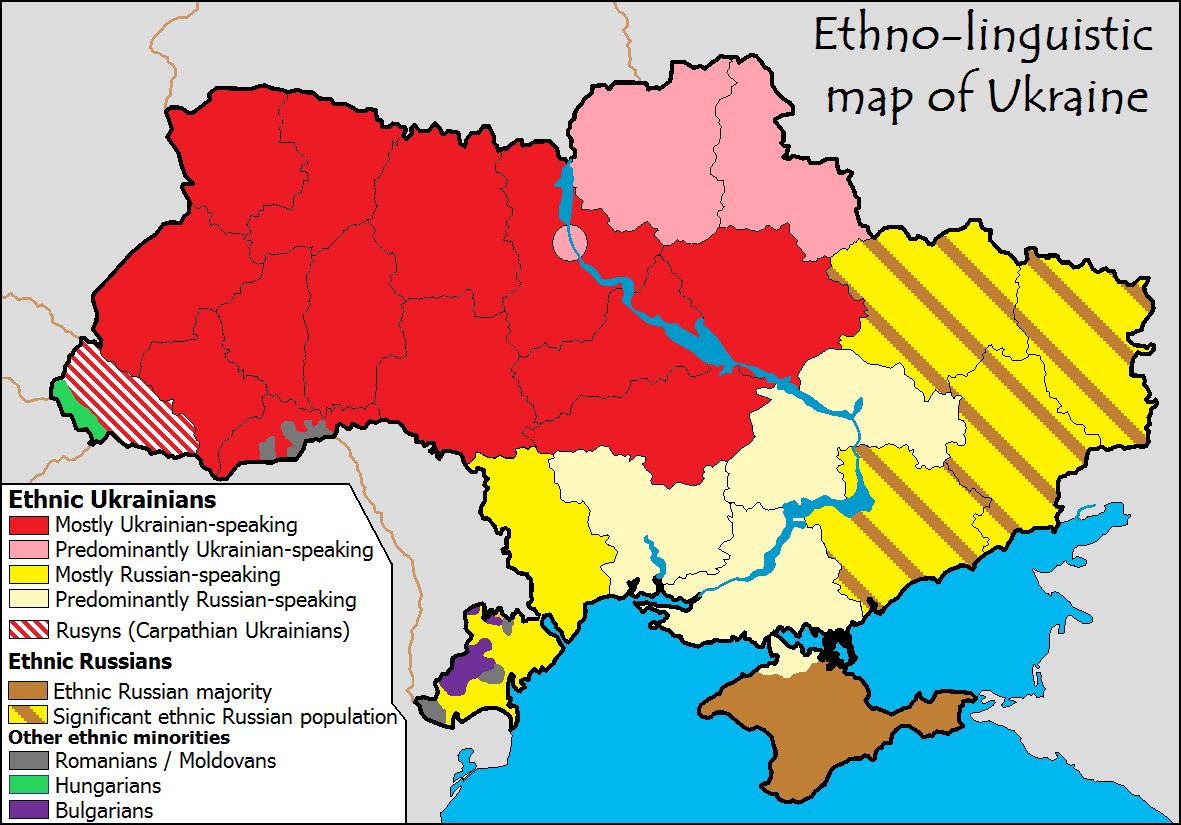

Within Ukraine, Russian persists as a significant minority language, though its status has seen considerable shifts. Estimates from 2004 indicated 14.4 million native speakers and 29 million active speakers in the country. In 2006, 65% of the population was fluent in Russian, and 38% used it as their primary language. However, recent legislative developments have prioritized Ukrainian. The 2017 education law mandates at least partial instruction in Ukrainian in all schools, while allowing for indigenous and national minority languages. This law, however, drew criticism from Russia and Hungary. The 2019 Law of Ukraine “On protecting the functioning of the Ukrainian language as the state language” further elevated Ukrainian’s priority in over 30 spheres of public life, from administration to media and education, though it does not regulate private communication. Public sentiment has also shifted dramatically: a March 2022 poll revealed that 83% of respondents believe Ukrainian should be the sole state language, a significant increase from pre-war levels, when nearly a quarter favored Russian as a state language. After Russia’s full-scale invasion, support for Russian’s state language status plummeted to just 7%. An August 2023 survey further confirmed this trend, with almost 60% speaking Ukrainian at home, about 30% speaking both, and only 9% exclusively speaking Russian. The use of Russian in daily life has noticeably decreased since March 2022, reflecting a profound societal change.

Beyond the immediate post-Soviet sphere, Russian’s influence extends deeply into the Caucasus and Central Asia. In Armenia, while lacking official status, Russian is recognized as a minority language. In 2006, 30% of the population was fluent. In Azerbaijan, it serves as a lingua franca, with 26% of the population fluent in 2006. Georgia also recognizes Russian as a minority language, and it is cited as the country’s de facto working language, spoken by 9% of the population. Across Asia, pockets of Russian speakers and historical influences persist.