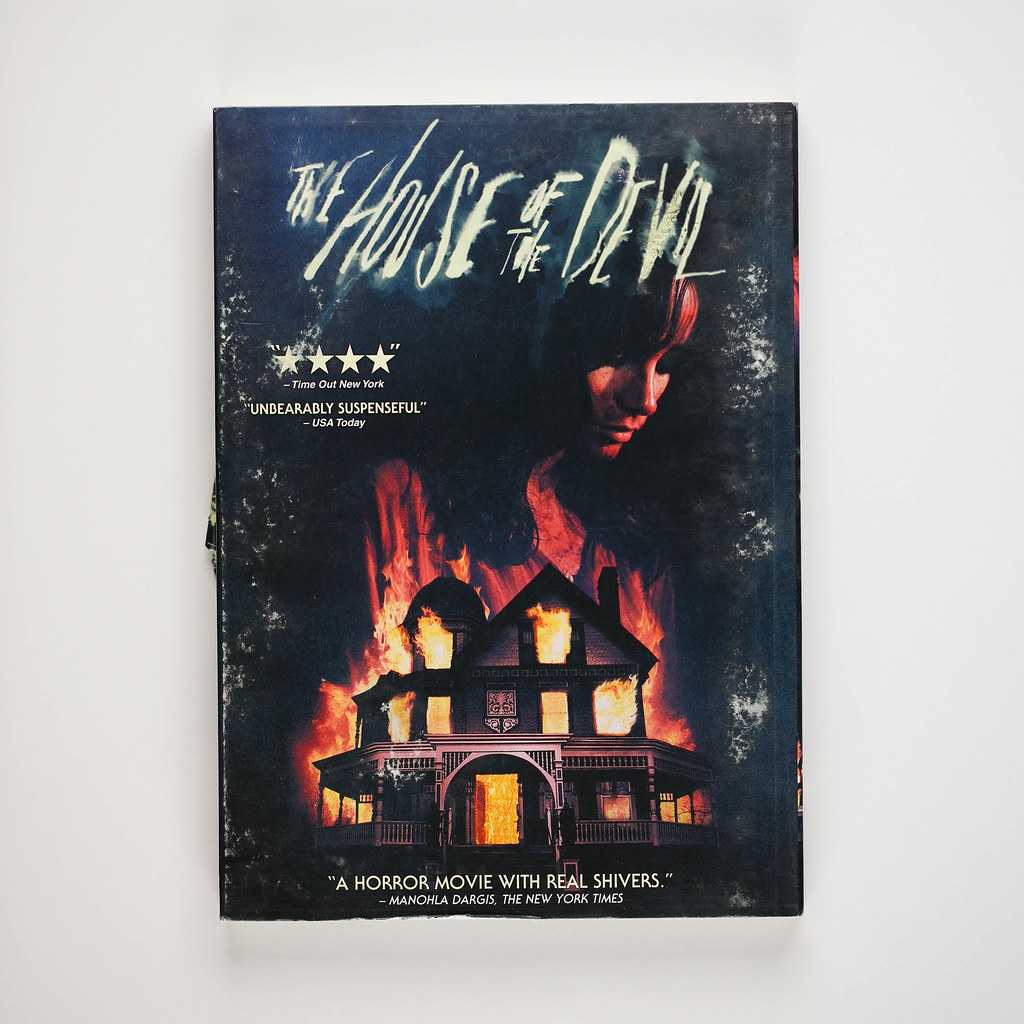

In the annals of cinematic history, few films hold as pivotal a place as Georges Méliès’ 1896 silent marvel, ‘The House of the Devil.’ Known by various titles such as ‘Le Manoir du diable’ in France, ‘The Haunted Castle’ in the United States, and ‘The Devil’s Castle’ in the United Kingdom, this remarkable short is more than just an early moving picture; it is widely acknowledged as the world’s very first horror film. Its brief yet impactful frames laid the groundwork for a genre that would, over the next century and beyond, continuously challenge and captivate audiences, delving into the depths of human emotion and societal reflection.

At a time when cinema was in its absolute infancy, Méliès, a master of pioneering film techniques and an accomplished magician, conjured a visual narrative unlike anything audiences had ever seen. He transformed the nascent medium into a playground for innovation, crafting fantastical illusions that transcended mere documentation. This particular film, originally intended to evoke amusement and wonder, paradoxically became the unwitting progenitor of screen terror, setting a profound precedent for how fear, fantasy, and the uncanny would be depicted on film.

As senior editors, we often reflect on the foundational works that shaped the industries we cover. ‘The House of the Devil’ stands as a towering testament to this legacy, embodying the inherent curiosity, fear, and wonder of a society in flux at the cusp of the 20th century. Join us as we meticulously explore the intricate details of this cinematic gem, dissecting its production, unraveling its plot, and appreciating its groundbreaking contribution to the art form.

1. **The Genesis of a Genre: ‘The House of the Devil’ as the First Horror Film**’The House of the Devil,’ a French silent trick film directed by Georges Méliès, stands as a monumental entry in cinema history, primarily for its designation as the very first horror film. Released in 1896, this classification is attributed not to its original intent, which was to entertain and inspire wonder, but rather to its thematic content and the characters it so vividly brought to life. The film’s brief pantomimed sketch introduces audiences to an encounter with the Devil and various attendant phantoms, elements that would become staples of the horror genre.

The film’s characters and themes include evocative images of demons, bats transforming into the devil, ghosts reminiscent of gothic tales, witches evoking anxieties about pagan folklore, and even a skeleton. While Méliès’s primary goal was amusement, the sheer presence of these supernatural and unsettling figures, along with their eerie transformations and appearances, established a conceptual blueprint for cinematic horror. It demonstrated the medium’s capacity to conjure the uncanny and the macabre, inadvertently defining what a “horror film” might technically entail.

Though not designed to induce terror in the modern sense, ‘The House of the Devil’ broke new ground by placing supernatural malevolence and dark fantasy squarely at its narrative core. This bold thematic choice, combined with Méliès’s innovative visual trickery, marked the true inception of a genre dedicated to exploring the shadows of human experience and imagination on the silver screen. It was a crucial, albeit perhaps accidental, step toward the sophisticated and fear-inducing horror cinema we know today.

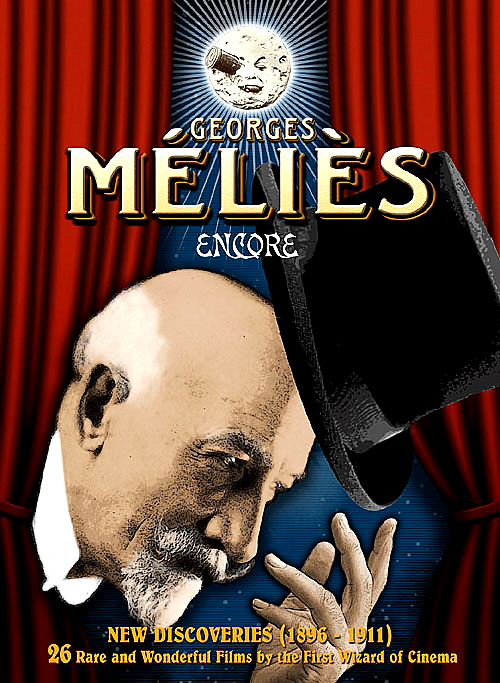

2. **Georges Méliès: The Visionary Director and His Pioneering Spirit**At the heart of ‘The House of the Devil’ lies the unparalleled genius of Georges Méliès. Not merely the director, Méliès was also the producer of this groundbreaking work, operating under his own Star Film Company. His background as a stage magician profoundly influenced his approach to filmmaking, as he saw the camera not just as a tool for recording reality but as a magical instrument capable of creating impossible illusions. This unique perspective allowed him to push the boundaries of early cinema, transforming it from a novelty into an art form.

His studio, commonly known as the Star Film Company, was a hub of innovation, systematically cataloging its productions. ‘The House of the Devil’ itself was numbered 78–80 in its catalogues at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin in Paris, illustrating Méliès’s methodical approach to his burgeoning cinematic empire. He meticulously crafted each frame, imbuing his films with a sense of wonder and enchantment. His profound understanding of theatrical illusion directly translated into pioneering cinematic techniques, establishing him as a crucial figure in the development of narrative film and special effects.

Méliès’s inventive spirit is palpable in ‘The House of the Devil,’ where every visual trick serves to enhance the fantastical narrative. His ability to conceive and execute such complex illusions with the limited tools of his era speaks volumes about his visionary mind. He wasn’t just telling a story; he was conjuring a spectacle, and in doing so, he laid foundational elements for visual storytelling that continue to resonate within filmmaking to this day. His mastery of the medium truly made him cinema’s first wizard.

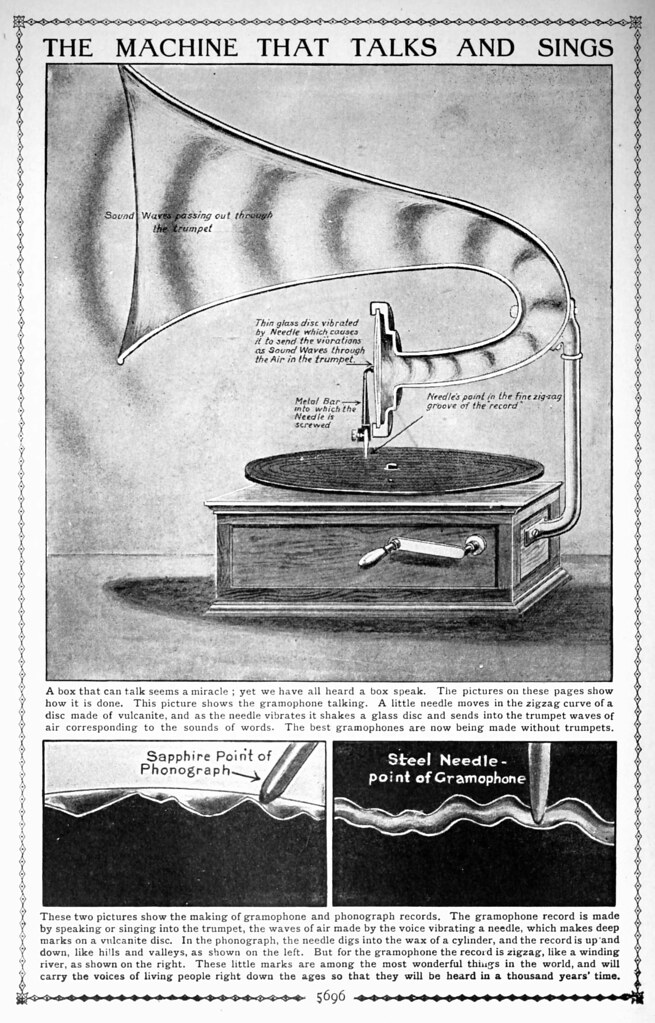

3. **Trick Film Innovation: The Magic Behind the Visuals**’The House of the Devil’ is a quintessential example of Méliès’s celebrated “trick film” style, a genre he virtually invented and perfected. These films were characterized by their reliance on innovative cinematic illusions and special effects, designed to astound and delight audiences. In this particular film, Méliès masterfully employs stop-motion effects, multiple exposures, and other ingenious techniques to achieve seemingly magical transformations and disappearances, all without the aid of modern technology.

The narrative unfolds through a series of astonishing visual deceptions. For instance, the film opens with a giant bat flying into a medieval castle, only to suddenly transform into the Devil himself. Later, the Devil’s assistant instantaneously teleports to different areas of the room, confusing the cavaliers. Perhaps most notably, a skeleton appearing before a cavalier turns first into a bat, then back into Mephistopheles, showcasing a seamless fluidity of transformation that was revolutionary for its time. Another striking moment involves the beautiful woman conjured from the cauldron, who transforms before the cavalier’s eyes into a withered old crone and then a group of six crones.

As Christopher Ripley observes in ‘Universal Monsters: Origins,’ “Though technology did not exist to create such visuals, Méliès used limited tools and his imagination to create a relatively impressive production.” This insight perfectly encapsulates the film’s technical brilliance. Méliès’s reliance on ingenuity and imagination, rather than advanced machinery, allowed him to create a production that was both visually impressive and deeply influential. These early trick effects were not mere novelties; they were the nascent language of visual storytelling, paving the way for all future special effects in cinema.

4. **The Narrative Unveiled: A Detailed Look at the Plot of ‘Le Manoir du diable’**The plot of ‘The House of the Devil’ is a brief yet remarkably eventful pantomimed sketch, unfolding with a theatrical flair. The film commences with a striking visual: a giant bat majestically flying into a medieval castle. This bat then undergoes an immediate and dramatic transformation, morphing suddenly into the imposing figure of the Devil, often referred to as Mephistopheles. Once established, Mephistopheles proceeds to conjure a cauldron and an assistant, who then aids him in summoning a woman from within the depths of the bubbling vessel.

Shortly after, the room clears, setting the stage for the arrival of two cavaliers. The Devil’s assistant then begins to poke their backs, before instantaneously teleporting to various parts of the room, creating confusion and leading one of the cavaliers to flee in fright. The second cavalier, however, remains, bravely enduring a series of tricks. Furniture moves autonomously, and a skeleton abruptly appears, challenging the cavalier’s resolve. Unfazed, the cavalier draws his sword and attacks the skeleton, which then startlingly transforms into a bat, before ultimately reverting to Mephistopheles.

The narrative escalates as Mephistopheles conjures four shrouded spectres, effectively subduing the resilient cavalier. As the dazed man recovers from this ethereal assault, he is then presented with the woman who was earlier conjured from the cauldron, her beauty clearly impressing him. However, his admiration is short-lived, as Mephistopheles, in a cruel twist, transforms her into a withered old crone, who then, in a further metamorphosis, becomes a group of six crones. The first cavalier returns, briefly showcasing bravery before leaping over the balcony’s edge to escape the crones. Finally, with the crones vanished, the Devil confronts the second cavalier, who, armed with a large crucifix, brandishes it heroically, causing the Devil to vanish, thus bringing the fantastical ordeal to its conclusion.

5. **Reception and Intent: Amusement, Wonder, and Unintended Terror**Understanding the reception of ‘The House of the Devil’ requires acknowledging its original artistic intent. Méliès designed this film not to instill fear, but rather to evoke “amusement and wonder from its audiences.” It was conceived as a theatrical comic fantasy, a brief pantomimed sketch that leveraged the nascent technology of cinema to create lighthearted, magical illusions. The goal was to entertain, to dazzle viewers with visual tricks and fantastical transformations, transporting them to a world of whimsical enchantment rather than spine-chilling dread.

Indeed, contemporary accounts and analyses, such as that by Christopher Ripley in ‘Universal Monsters: Origins,’ confirm this initial reception. Ripley notes, “If Méliès was shooting for terror, he fell short of the mark. Initially the film was amusing to its audience, rather than terror-inducing…” This highlights a fascinating paradox: a film that, by modern standards and technical classification, is considered the first horror film, was primarily experienced as a source of novelty and entertainment by its original viewers. The elements that we now associate with horror—devils, spectres, transformations—were then perceived through a lens of magical spectacle.

Yet, it is precisely because of its themes and characters that ‘The House of the Devil’ has earned its technical classification as the first horror film, despite its intent. The depiction of a human transforming into a bat, the conjuring of phantoms, and the confrontation with the Devil, all inherently dark and unsettling concepts, planted the seminal seeds for a genre dedicated to exploring the macabre. Méliès, perhaps unwittingly, harnessed the power of the moving image to bring these archetypal figures of dread to life, thereby laying the thematic and visual groundwork for countless frightful tales to come, forever cementing its place as a genre-defining masterpiece.

Having meticulously explored the foundational elements and initial impact of Georges Méliès’s ‘The House of the Devil,’ our journey into its enduring legacy deepens. This cinematic marvel not only ignited the horror genre but also carved out unique historical classifications and mirrored profound societal currents. Its brief frames hold a vast tapestry of influence, extending far beyond its initial release to shape the very narrative of early cinema.

Join us now as we examine the subsequent ripples this film created, from its surprising second classification as the first vampire film to its ambitious length for its time, its miraculous rediscovery, and the unique instance of its own remake. We will also delve into how this early work profoundly reflected the anxieties of its era, ultimately situating it within the broader, burgeoning landscape of early horror cinema, revealing its critical role in the art form’s evolution.

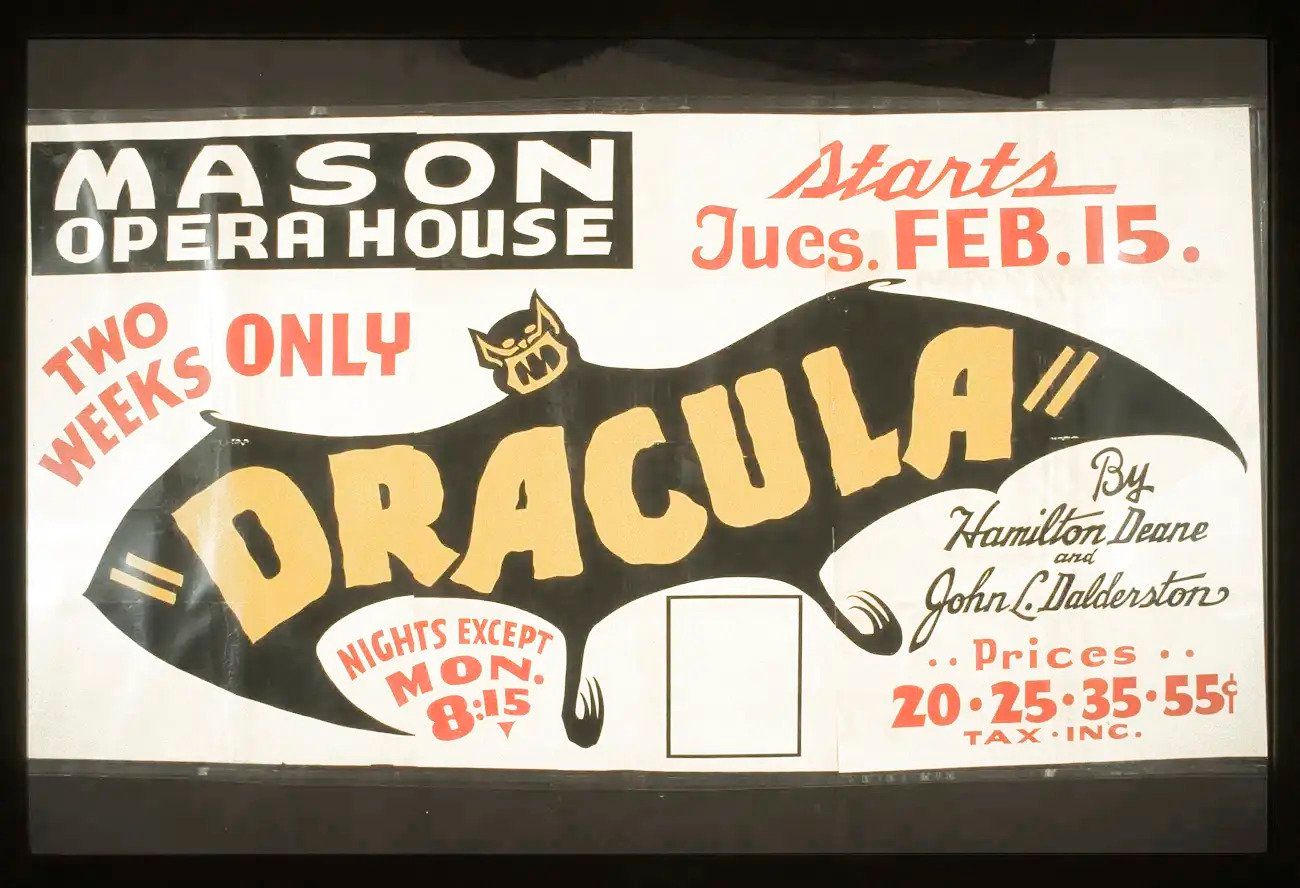

6. **The First Vampire Film: A Cinematic Transfusion**Beyond its designation as the seminal horror film, ‘The House of the Devil’ holds a fascinating additional classification: it has been labeled by some observers as the world’s first vampire film. This distinction is rooted in a pivotal plot element where a human undergoes a dramatic transformation into a bat. The very act of this metamorphosis, which later reverts to the demonic figure of Mephistopheles, directly invokes the shapeshifting abilities commonly associated with vampire lore.

While the film does not feature a traditional blood-drinking count, the mere presence of a bat, a creature intrinsically linked to the vampire archetype, transforming from and into a human figure, established a visual precedent for embodying supernatural evil through animalistic guise. This early cinematic trick harnessed the potent symbolism of the bat, inadvertently laying visual groundwork for countless frightful tales of the undead to come. It was a subtle yet powerful injection of what would become a cornerstone of vampire cinema.

Méliès, a magician by trade, perhaps intended this transformation purely as a spectacle of wonder, yet its thematic resonance proved profound. This early depiction, even as a “trick,” demonstrated the medium’s capacity to visually manifest the uncanny and the monstrous in ways that would inspire future filmmakers exploring the mythology of creatures of the night. It marked a rudimentary but crucial step in translating the ancient folklore of vampires into a nascent cinematic language.

7. **An Unprecedented Pace: The Ambitious Running Time**In an era when films were often mere seconds long, serving as brief curiosities rather than narrative experiences, ‘The House of the Devil’ made a bold statement with its ambitious running time of over three minutes. At 60 meters of film, this duration was a significant departure from the fleeting spectacles that dominated early cinematic offerings. Méliès’s decision to extend the film’s length demonstrated a clear vision for cinema as a medium capable of unfolding a more intricate story, even if presented as a “brief pantomimed sketch.”

This extended duration was not merely a technical achievement; it was a narrative one. It allowed Méliès to orchestrate a series of complex tricks and transformations, from the bat’s initial entry and transformation into the Devil, to the conjuring of a woman, furniture moving autonomously, and the multiple metamorphoses of the skeleton and the crones. Such an array of visual deceptions required more time to unfurl, showcasing a progression in storytelling that transcended the simple single-shot films of the period.

The film’s length underscored Méliès’s understanding of the burgeoning medium’s potential to captivate an audience over a sustained period. It moved beyond the fleeting wonder of a single trick to build a mini-narrative arc, albeit a fantastical one. This deliberate expansion of runtime was instrumental in paving the way for the development of more elaborate narrative films, marking ‘The House of the Devil’ as an early pioneer in cinematic ambition.

8. **From Obscurity to Preservation: The Remarkable Rediscovery**For many decades, ‘The House of the Devil’ was presumed lost to the annals of history, a silent ghost of early cinema. However, its fate took a remarkable turn in 1988 when a copy was unexpectedly found in the New Zealand Film Archive. This rediscovery was nothing short of miraculous, a testament to the persistent efforts of archivists and the serendipity of preservation.

The journey of this particular copy is as intriguing as the film itself. It had been purchased at a junk shop in Christchurch, New Zealand, sometime between the 1930s and 1940s. For years, its historical significance remained unrecognized, lying dormant until 1985 when its true identity and monumental value were finally understood. This incredible find brought back to light a cornerstone of film history, allowing a new generation to witness the genesis of cinematic horror.

The rediscovery of ‘The House of the Devil’ was a monumental event for film historians and enthusiasts worldwide. It offered invaluable insights into Méliès’s early filmmaking techniques, narrative structures, and the broader evolution of cinema. This preserved copy not only rekindled interest in Méliès’s work but also underscored the critical importance of film preservation, ensuring that foundational works like this continue to inform and inspire.

9. **The Echo of Innovation: Méliès’s Notable Remake**In a curious twist of early cinematic history, Georges Méliès himself produced a single remake of ‘The House of the Devil’ just one year after its initial release. Titled ‘Le Château hanté’ (The Haunted Castle), this subsequent production, made in 1897, has often been a source of confusion for film scholars and audiences alike. The shared theme of a haunted edifice and the similar English release titles only added to this historical entanglement.

The confusion between the original ‘The House of the Devil’ and its 1897 remake, ‘Le Château hanté,’ is understandable given the rudimentary cataloging and distribution methods of the era. Both films explore similar supernatural themes, featuring a castle, mysterious occurrences, and Méliès’s signature trickery. This overlap highlights the challenges in definitively identifying early cinematic works, particularly when a prolific filmmaker like Méliès frequently revisited successful concepts.

The decision by Méliès to remake his own work so swiftly suggests an ongoing process of experimentation and refinement. It illustrates his continuous quest to improve upon his existing formulas, perhaps to incorporate new tricks or simply to capitalize on the popularity of the original theme. This early example of a remake, initiated by the original creator, offers a fascinating glimpse into the nascent commercial and artistic strategies of cinematic production.

10. **A Collective Reflection: Societal Anxieties at the Turn of the Century**’The House of the Devil,’ though intended for “amusement and wonder,” profoundly reflects the collective consciousness and societal anxieties brewing at the turn of the 20th century. Its imagery, replete with “demons that call back to ancient myths, bats that transform into the devil, ghosts reminiscent of gothic tales, witches that evoked anxieties about pagan folklore,” and even a skeleton, tapped into a primal fascination with the unknown and the supernatural. This was an era of immense flux, marked by rapid scientific advancements, sweeping societal reforms, and the expansion of artistic and literary horizons.

The film’s exploration of these unsettling figures and transformations served as a subtle mirror to the era’s palpable blend of excitement and uncertainty. As societies across Europe grappled with new technologies and shifting worldviews, the film provided a metaphorical outlet for inherent curiosities and underlying fears. It presented a visual dialogue with a public navigating the complexities of progress, where the lines between the known and the mystical often blurred.

From its very inception, horror cinema, as exemplified by Méliès’s pioneering work, carved a distinct niche for itself. It became a genre that dared to delve deeper, to critically question, and to profoundly reflect the unspoken concerns of its time. ‘The House of the Devil’ stands not merely as an early cinematic experiment but as a poignant snapshot of an era’s collective psyche, illuminating how fear and wonder intertwine in the human experience.

11. **Charting the Shadows: ‘The House of the Devil’ in Early Horror Cinema**’The House of the Devil’ stands as a pivotal foundation stone, setting the stage for what would become a fervent love letter to human emotion and societal reflection within cinema. Its groundbreaking efforts ushered in an era where film became a playground for innovation, rapidly gaining global popularity and prompting a “dizzying array of adaptations” of dark, eerie tales in quick succession. This period, often termed “horror-mania,” saw filmmakers eagerly explore the macabre, cementing horror’s place in the cinematic world.

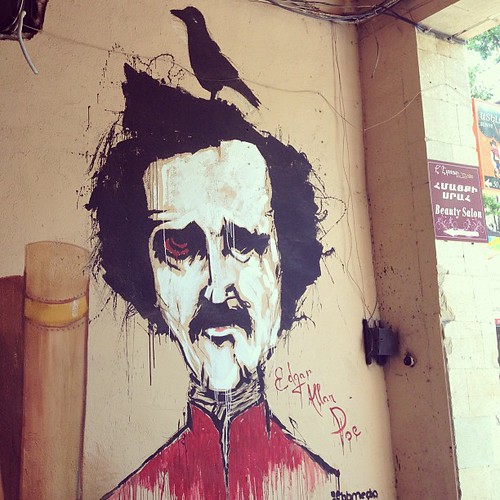

The early 20th century witnessed a significant interest in literary adaptations, most notably from the works of Edgar Allan Poe, with French and American filmmakers producing versions like ‘Le Puits et le Pendule’ (1909) and ‘The Sealed Room’ (1909). Iconic figures like Frankenstein’s monster came alive in Edison’s ‘Frankenstein’ (1910) and again in the Italian ‘Il mostro di Frankenstein’ (1921). Oscar Wilde’s enigmatic ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’ saw international adaptations, as did Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde,’ which even saw three separate adaptations in 1920 alone. Pioneering figures like German actor-director Paul Wegener, renowned for his ‘Golem’ films, and the influential ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ (1920), starring Werner Krauss and Conrad Veidt, further solidified the genre’s artistic merit.

This burgeoning landscape culminated in masterpieces like F. W. Murnau’s ‘Nosferatu’ (1922), an unparalleled adaptation of Dracula that chillingly captured Europe’s post-war dread and anxieties related to pandemics like the Spanish flu. Meanwhile, Hollywood embarked on its own horror journey with atmospheric films like ‘The Phantom of the Opera’ (1925) and ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’ (1931), which masterfully mirrored American societal apprehensions and the nation’s struggle during the Great Depression. These films, emerging from the groundwork laid by ‘The House of the Devil,’ demonstrated that horror was never just about spectacle; it was about confronting societal shadows and providing profound social commentaries, continually challenging and captivating its audience by delving into the human psyche’s darker corners.

From the first flicker of ‘The House of the Devil’ to the expansive, psychologically rich narratives that followed, horror cinema has consistently proven its unique capacity to connect with our deepest fears and most profound reflections. Georges Méliès, with his initial, enchanting foray into the macabre, did more than just create a film; he opened a portal to a world where the screen mirrors the very essence of human experience, fear, and wonder, establishing a legacy that continues to resonate with powerful clarity today.