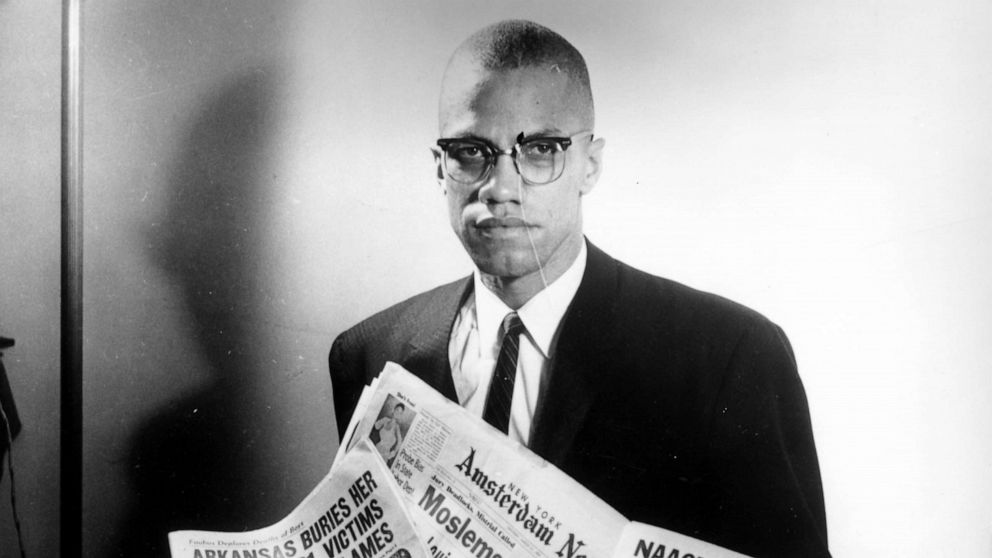

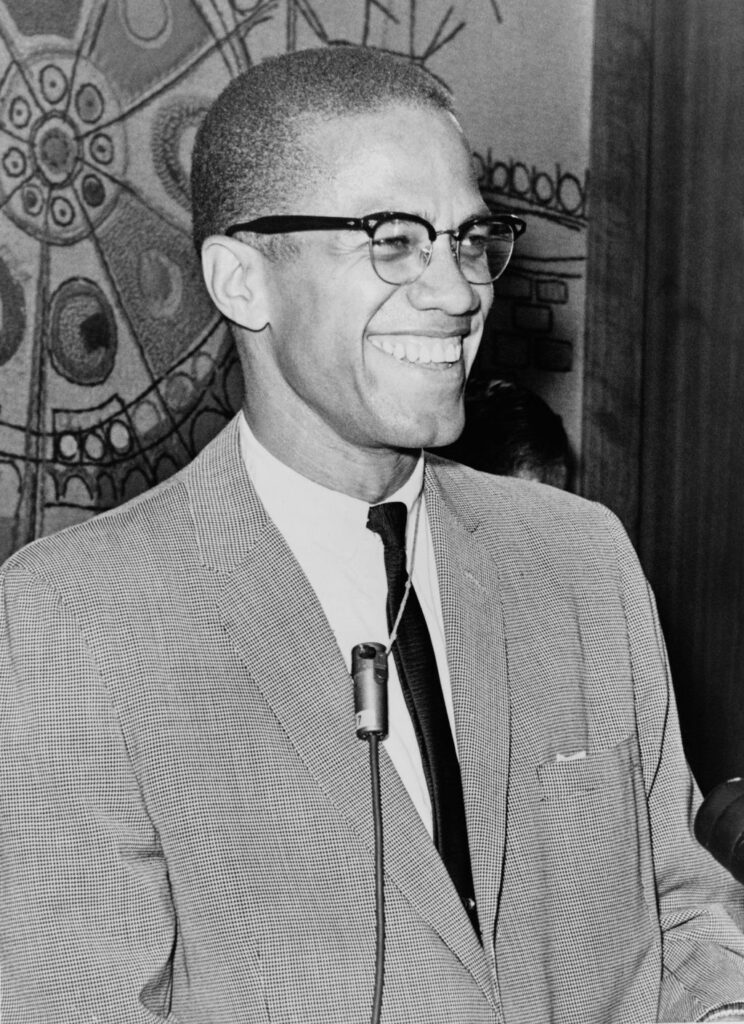

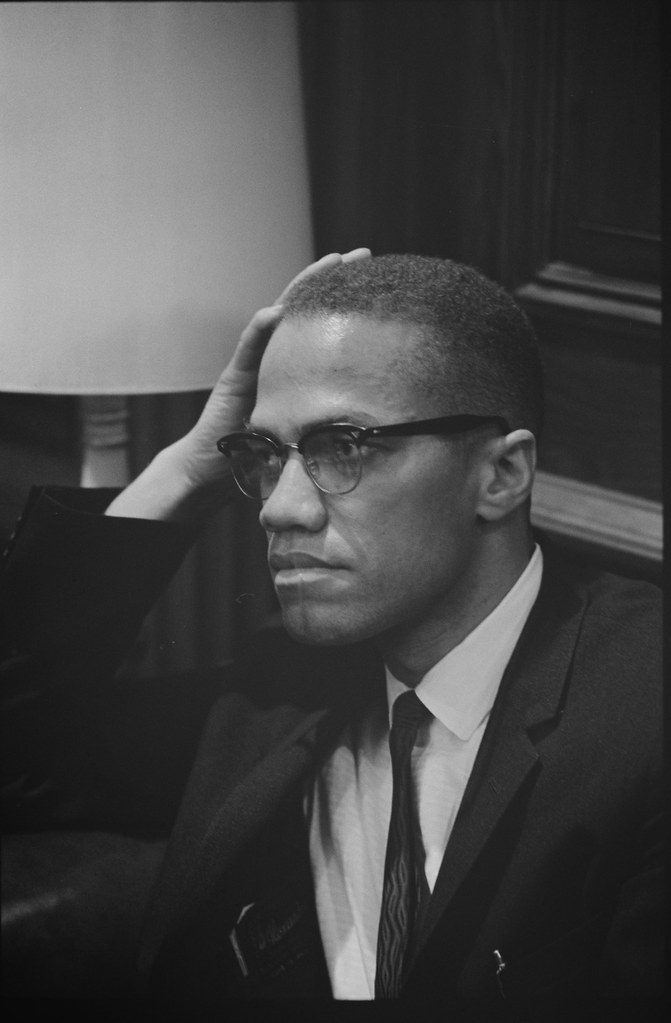

Malcolm X, born Malcolm Little and later known as el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, stands as a complex and formidable figure in American history, an African American revolutionary, Muslim minister, and human rights activist whose prominence during the civil rights movement remains undeniable. His journey from a troubled youth to a vocal advocate for Black empowerment and racial justice was marked by profound personal transformation and ideological evolution, shaping the discourse on civil rights in the mid-20th century. While sometimes accused of preaching violence, he is equally celebrated within African American and Muslim communities for his unwavering pursuit of racial justice.

His life, spanning just under four decades, offers a compelling narrative of resilience, intellectual awakening, and courageous advocacy against systemic oppression. From the depths of a criminal past to the global stage, Malcolm X challenged established norms, articulated the frustrations of many African Americans, and ultimately sought a broader, more inclusive vision of human dignity. This article delves into the pivotal moments and transformations that defined his extraordinary life, providing a comprehensive account of his journey and its lasting impact.

We embark on a meticulous examination of Malcolm X’s trajectory, beginning with the challenging circumstances of his childhood and adolescence. We will trace his early encounters with racial injustice, his immersion in a life of crime, and the profound intellectual and spiritual awakening he experienced during his incarceration. This exploration will illuminate the foundational experiences that shaped his formidable intellect and impassioned resolve, leading to his emergence as a prominent voice in the Nation of Islam and, subsequently, a global advocate for human rights.

1. **A Childhood Forged in Adversity: The Early Years of Malcolm Little (1925-1937)**Malcolm Little was born on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, the fourth of seven children to Grenada-born Louise Little (née Langdon) and Georgia-born Earl Little. His father, Earl, was an outspoken Baptist lay speaker and a local leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Both parents admired the Pan-African activist Marcus Garvey, and Louise served as the organization’s secretary and “branch reporter” for Negro World, fostering values of self-reliance and black pride in their children.

Life for the Little family was fraught with peril, compelling them to relocate due to threats from white supremacist groups. In 1926, they moved to Milwaukee, and shortly thereafter to Lansing, Michigan, where the family endured frequent harassment from the Black Legion, a white racist group. Earl Little accused this group of burning down their family home in 1929, an incident that underscored the pervasive racial animosity they faced.

Tragedy struck when Malcolm was six years old, with his father’s death officially ruled a streetcar accident. However, his mother, Louise, firmly believed Earl had been murdered by the Black Legion, a rumor that circulated widely and deeply disturbed Malcolm X throughout his childhood. As an adult, he expressed conflicting beliefs regarding the circumstances of his father’s demise. Following a dispute, Louise received a life insurance benefit of nominally $1,000, paid in installments of $18 per month, while another larger policy was refused on claims of suicide. To sustain her family, Louise rented out parts of her garden, and her sons hunted game, exemplifying the family’s struggle for survival.

2. **Early Disillusionment and the Abandonment of Educational Aspirations (1937-1941)**The challenging environment of Malcolm’s early life continued through his adolescence. In 1937, a man Louise had been dating vanished after she became pregnant with his child, further destabilizing the family. By late 1938, Louise suffered a nervous breakdown and was committed to Kalamazoo State Hospital, leading to the separation of her children into foster homes. Malcolm and his siblings would eventually secure her release 24 years later, a testament to the enduring impact of this traumatic period.

Despite the turmoil, Malcolm displayed academic promise, excelling in junior high school while attending West Junior High School in Lansing and later Mason High School in Mason, Michigan. His aspirations were clear: he wished to pursue a career in law. However, this dream was abruptly shattered by a dismissive remark from a white teacher, who told him that practicing law was “no realistic goal for a nigger.”

This pivotal moment in his high school years profoundly shaped his perception of racial barriers. Malcolm X later recalled feeling that the white world offered no place for a career-oriented Black man, regardless of talent. This stark realization led him to drop out of high school in 1941, before graduating, signaling a profound disillusionment with the societal structures that seemed determined to limit his potential.

3. **A Descent into Criminality: The Path of “Detroit Red” (1941-1946)**Following his departure from high school, Malcolm spent the years between ages 14 and 21 engaged in a variety of jobs. He lived with his half-sister, Ella Little-Collins, in Roxbury, a predominantly African American neighborhood in Boston. This period marked a significant shift from his earlier academic promise to a burgeoning involvement in illicit activities, as he navigated the complex social landscapes of urban America.

In 1943, after a brief period in Flint, Michigan, Malcolm relocated to New York City’s vibrant Harlem neighborhood. There, he secured employment on the New Haven Railroad but also became deeply entangled in a criminal underworld. His activities included drug dealing, gambling, racketeering, robbery, and pimping. It was during this time that he befriended John Elroy Sanford, a fellow dishwasher who would later gain fame as comedian Redd Foxx. Both men had reddish hair, earning Sanford the nickname “Chicago Red” and Malcolm the moniker “Detroit Red,” reflecting his hometown.

His brushes with authority extended to his attempts to evade military service during World War II. In late 1943, summoned by the local draft board, Malcolm feigned mental disturbance by rambling and declaring, “I want to be sent down South. Organize them nigger soldiers … steal us some guns, and kill us [some] crackers.” This dramatic performance led to him being declared “mentally disqualified for military service.” By late 1945, Malcolm returned to Boston, where he and four accomplices committed a series of burglaries targeting wealthy white families, ultimately leading to his arrest in 1946 while attempting to retrieve a stolen watch left for repairs.

4. **Incarceration and the Awakening to the Nation of Islam (1946-1950)**In February 1946, Malcolm Little began serving an eight-to-ten-year sentence at Charlestown State Prison for larceny and breaking and entering, a confinement that would prove to be a transformative period in his life. He was subsequently transferred to Concord Reformatory in 1947, where he served 15 months, before a final transfer to Norfolk Prison Colony. It was within these prison walls that he embarked on an intense journey of self-education, laying the intellectual groundwork for his future activism.

His intellectual awakening was significantly influenced by a fellow convict, John Bembry, a self-educated man whom Malcolm would later describe as “the first man I had ever seen command total respect … with words.” Under Bembry’s mentorship, Malcolm developed a “voracious appetite for reading,” meticulously copying dictionary entries and immersing himself in various texts. This dedication to learning marked a profound departure from his previous life of crime, signaling a new direction for his intellectual and spiritual energies.

During this period, several of Malcolm’s siblings began writing to him about the Nation of Islam, a burgeoning religious movement advocating Black self-reliance and the eventual return of the African diaspora to Africa, free from white American and European domination. Initially, Malcolm showed “scant interest.” However, a letter from his brother Reginald in 1948, advising him to “don’t eat any more pork and don’t smoke any more cigarettes. I’ll show you how to get out of prison,” prompted an almost instantaneous change in his habits. Following a visit where Reginald detailed the group’s teachings, including the notion that white people were considered devils, Malcolm reflected on his past relationships with white individuals, concluding that they had all been characterized by dishonesty, injustice, greed, and hatred. Receptive to the Nation of Islam’s message, especially given his hostility to Christianity which earned him the prison nickname “Satan,” he began to embrace its tenets.

5. **Embracing a New Identity: Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam (1950-1952)**In late 1948, a pivotal moment arrived when Malcolm wrote to Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam. Muhammad responded with guidance, advising Malcolm to renounce his past, humbly bow in prayer to God, and promise never to engage in destructive behavior again. Though he later recounted an intense “inner struggle” before he could bring himself to bend his knees in prayer, Malcolm soon committed himself to the Nation of Islam, initiating a regular and significant correspondence with Muhammad that would profoundly influence his trajectory.

His growing prominence and new affiliations did not go unnoticed by federal authorities. In 1950, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) initiated a file on Malcolm after he sent a letter from prison to President Harry S. Truman, expressing his opposition to the Korean War and declaring himself a communist. This marked the beginning of official surveillance that would shadow him for decades, reflecting the government’s concern over his emerging influence and radical views.

It was also in 1950 that Malcolm began signing his name “Malcolm X,” a symbolic act deeply rooted in the Nation of Islam’s teachings. Muhammad instructed his followers to discard their family names upon joining the organization, replacing them with “X” until he would, at the appropriate time, reveal their “original name.” In his posthumously published autobiography, Malcolm X eloquently explained that the “X” symbolized the true African family name he could never ascertain, serving as a powerful rejection of “the white slavemaster name of ‘Little’ which some blue-eyed devil named Little had imposed upon my paternal forebears.” This new identity marked his spiritual and ideological rebirth, signifying a complete break from his past and a profound embrace of his African heritage. After his parole in August 1952, he visited Elijah Muhammad in Chicago, solidifying his commitment to the movement.

6. **The Architect of Growth: Malcolm X’s Rise as a Nation of Islam Leader (1952-1957)**Following his parole in August 1952 and his visit with Elijah Muhammad in Chicago, Malcolm X rapidly ascended through the ranks of the Nation of Islam, becoming one of its most influential and dynamic leaders. His oratorical skills and unwavering dedication quickly made him a central figure in the organization’s expansion across the United States. In June 1953, he was appointed assistant minister of the Nation’s Temple Number One in Detroit, a key early step in his leadership journey.

His impact was immediate and widespread. Later that same year, he established Boston’s Temple Number 11, demonstrating his capacity for organizational development. By March 1954, he expanded Temple Number 12 in Philadelphia, and just two months later, he was selected to lead the critically important Temple Number 7 in Harlem, New York. Under his leadership, the Harlem temple experienced a rapid and significant increase in membership, solidifying his reputation as a powerful recruiter and inspiring speaker. This period also saw the FBI, which had initially focused on his possible communist associations, shift its surveillance to his swift ascent within the Nation of Islam.

Malcolm X’s recruitment prowess continued throughout 1955, as he established new temples in Springfield, Massachusetts (Number 13); Hartford, Connecticut (Number 14); and Atlanta (Number 15). These efforts resulted in hundreds of African Americans joining the Nation of Islam every month, dramatically increasing the organization’s reach and influence. Beyond his formidable speaking ability, Malcolm X possessed an impressive physical presence, standing 6 feet 3 inches tall and weighing approximately 180 pounds. Writers of the era described him as “powerfully built” and “mesmerizingly handsome … and always spotlessly well-groomed,” attributes that undoubtedly enhanced his commanding public persona.

7. **The Hinton Johnson Incident: Malcolm X on the National Stage (1957)**Malcolm X’s emergence into broader public awareness was significantly catalyzed by the Hinton Johnson incident in 1957. On April 26, Hinton Johnson, a Nation of Islam member, and two other members intervened when they witnessed two New York City police officers beating an African American man with nightsticks. Their shouts of “You’re not in Alabama … this is New York!” were met with aggression, as one officer brutally beat Johnson, inflicting brain contusions and subdural hemorrhaging. All four African American men involved were subsequently arrested.

Upon being alerted by a witness, Malcolm X, accompanied by a small group of Muslims, promptly arrived at the police station, demanding to see Johnson. Initially, police denied holding any Muslims. However, as the crowd outside swelled to approximately five hundred people, they relented, allowing Malcolm X to speak with Johnson. After assessing the severity of Johnson’s injuries, Malcolm X insisted on arranging an ambulance to transport Johnson to Harlem Hospital, demonstrating his resolute commitment to protecting his community members.

By the time Johnson was returned to the police station after receiving medical treatment, an estimated four thousand people had gathered outside, a silent yet powerful demonstration of community solidarity. Inside the station, Malcolm X and an attorney were finalizing bail arrangements for two of the arrested Muslims. When police stated Johnson could not return to the hospital until his arraignment the following day, Malcolm X, recognizing an impasse, stepped outside and gave a simple hand signal. In a display of profound discipline, Nation members silently dispersed, followed by the rest of the crowd. This incident deeply impressed the authorities, with one police officer remarking to the New York Amsterdam News, “No one man should have that much power.” Within a month, the New York City Police Department initiated surveillance on Malcolm X and began inquiries with authorities in other cities and prisons where he had lived or served time, underscoring the perceived threat of his growing influence. Despite a grand jury declining to indict the officers who beat Johnson, Malcolm X’s angry telegram to the police commissioner in October ultimately led the police department to assign undercover officers to infiltrate the Nation of Islam, marking a significant escalation in official scrutiny of his activities.

8. **Expanding Influence: National Media and International Connections (Late 1950s – Early 1960s)**Malcolm X’s prominence grew significantly in the late 1950s, reaching a national audience. He began using the name Malcolm Shabazz or el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, though he remained widely known as Malcolm X. His commentaries on issues were frequently reported across print, radio, and television, establishing him as a major public figure.

A pivotal moment for his media exposure was the 1959 New York City television broadcast, “The Hate That Hate Produced,” focusing on the Nation of Islam. This program dramatically increased public awareness of both the organization and Malcolm X. His potent rhetoric, articulating the frustrations of many African Americans, further cemented his role as a compelling, albeit controversial, voice.

Beyond domestic recognition, Malcolm X forged international connections, notably at the September 1960 United Nations General Assembly in New York City. He met global leaders like Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt and Fidel Castro, who, impressed by Malcolm X, invited him to visit Cuba. Malcolm X publicly praised Castro, calling him “the only white person I ever liked,” while privately telling the FBI he could not be a communist due to his belief in God.

9. **Core Doctrines and Critiques: Malcolm X’s Stance within the Nation of Islam**From 1952 until his 1964 departure, Malcolm X passionately promoted the Nation of Islam’s teachings. These included the belief that Black people were the world’s original inhabitants, and the controversial doctrine that White people were “devils.” This also prophesied the imminent demise of the White race.

Despite being labeled a racist, Louis E. Lomax argued critics misunderstood “biblical prophecy” and Malcolm X’s teachings. The Nation forbade members from political participation, contrasting with mainstream civil rights groups like the NAACP, which denounced Malcolm X as an irresponsible extremist.

Malcolm X strongly critiqued the civil rights movement, calling Martin Luther King Jr. a “chump” and other leaders “stooges” of the White establishment. He opposed racial integration, labeling the 1963 March on Washington a “farce on Washington.” He advocated complete separation, proposing a return to Africa or a separate country in America. Rejecting nonviolence, Malcolm X argued Black people should defend themselves “by any means necessary,” resonating powerfully with African Americans in northern and western cities.

10. **Seeds of Disillusionment: The LAPD Violence and Internal Conflicts (1961-1962)**The early 1960s initiated Malcolm X’s deep disillusionment with the Nation of Islam and Elijah Muhammad. A key event was the violent confrontations between Nation members and LAPD officers in late 1961 and early 1962 in South Central Los Angeles. Tensions escalated following initial arrests and acquittals.

On April 27, 1962, officers unprovokedly beat Muslims outside Temple Number 27. When a crowd emerged, more than 70 backup officers raided the mosque, indiscriminately beating members and shooting seven Muslims. Ronald Stokes, a Korean War veteran, was fatally shot while surrendering, and William X Rogers was paralyzed. The coroner ruled Stokes’s killing justified, and no officers were charged.

For Malcolm X, this violence and mosque desecration demanded action. He sought Elijah Muhammad’s approval to retaliate or collaborate with civil rights groups, but Muhammad denied both. This refusal, described by Louis X as a critical juncture, foreshadowed the deteriorating relationship and deepened Malcolm’s internal conflict.

11. **Deepening Rift: Muhammad’s Moral Compromises and Media Jealousy (1963)**Furthering Malcolm X’s disillusionment were rumors of Elijah Muhammad’s extramarital affairs with young Nation secretaries, a severe violation of Nation teachings. Initially, Malcolm dismissed these, but conversations in April 1963 with Muhammad’s son, Wallace, and the accusing women convinced him of their truth. Muhammad later confirmed the rumors, citing Biblical prophets for justification.

Malcolm X later revealed in national TV interviews (1964-1965) that Muhammad had confirmed multiple child rapes, resulting in seven pregnancies. He also disclosed an assassination attempt—an explosive device found in his car—and death threats, all linked to his exposure of Muhammad’s misconduct.

This period also saw media attention disproportionately focused on Malcolm X, stirring envy within the Nation. His autobiography drew publisher interest, and Louis Lomax’s 1963 book featured Malcolm X prominently with five of his speeches, compared to only one from Muhammad. This public profile disparity exacerbated tensions, with some Nation members seeing Malcolm X as a direct threat to Muhammad’s leadership.

12. **The Definitive Break: Establishing New Foundations (Early 1964)**On March 8, 1964, Malcolm X publicly announced his break from the Nation of Islam. While remaining a Muslim, he felt the Nation had “gone as far as it can” due to its rigid teachings. This marked a significant shift toward a more independent and inclusive path for Black empowerment.

He swiftly founded two new organizations: Muslim Mosque, Inc. (MMI), a religious home for Black Muslims, and the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), a secular group advocating Pan-Africanism and Black political consciousness. On March 26, 1964, he briefly met Martin Luther King Jr. in Washington, D.C., during a Senate debate on the Civil Rights bill, signaling potential, albeit fleeting, collaboration.

In April, Malcolm X delivered “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech, urging African Americans to vote wisely, but also cautioning that if equality remained elusive, taking up arms might become “necessary for them to take up arms.” In the weeks following his departure, he converted to Sunni Islam, a spiritual evolution that would influence his subsequent international engagements.

13. **A Global Vision: The Transformative Hajj and African Tour (Spring-Summer 1964)**In April 1964, with help from his half-sister Ella Little-Collins, Malcolm X began his Hajj to Mecca. His U.S. citizenship and lack of Arabic initially caused delays in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. However, Abdul Rahman Hassan Azzam’s son intervened, arranging his release, and Prince Faisal subsequently designated him a state guest.

After completing the Hajj rituals, Malcolm X met Prince Faisal. He later described how seeing Muslims of “all colors, from blue-eyed blonds to Black-skinned Africans” interacting as equals profoundly altered his perspective. This global brotherhood, he stated, revealed a powerful means to overcome racial problems, contrasting sharply with his experiences in the United States.

Following Mecca, Malcolm X embarked on an extensive African tour, meeting officials and speaking widely in nations like Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Ghana, and Algeria. He represented his OAAU at the Organization of African Unity meeting in Cairo, aiming to strengthen Black American-African ties. African leaders, including Kwame Nkrumah, even invited him to serve in their governments. He deeply treasured the honorary Yoruba name “Omowale” (the son who has come home), bestowed upon him in Nigeria.

14. **Challenging Imperialism: European Engagements and Critical Perspectives (Late 1964 – Early 1965)**

Returning from Africa in November 1964, Malcolm X spoke in Paris. In the U.S., he accused the country of imperialism in the Congo, criticizing support for Moïse Tshombe, an “Uncle Tom.” He claimed U.S. President Johnson and Tshombe were “in the same bed,” with U.S. financing propping up Tshombe’s government. He strongly condemned Operation Dragon Rouge, asserting a double standard in valuing White and Black lives, and concluded, “chickens come home to roost.”

On December 3, Malcolm X debated at the Oxford Union Society in the UK, arguing for “Extremism in the Defense of Liberty is No Vice; Moderation in the Pursuit of Justice is No Virtue.” The BBC televised the debate nationally. He purposefully presented himself as a Muslim who happened to be Black, reflecting his Sunni conversion and effort to shed his “angry Black Muslim extremist” image, mentioning religion only twice.

At Oxford, Malcolm X critiqued the Anglo-American press’s Congo portrayal, noting Simbas were “savages” while Tshombe and White mercenaries were favorably presented. He charged CIA-hired Cuban pilots indiscriminately bombed Congolese villages, ignored by media focusing on Simba “raping White women.” He stated Tshombe’s “extremism” was unlabelled because it was “endorsed by the West.” He also visited Smethwick, UK, comparing minority treatment to Jews under Hitler and warning against “gas ovens.”

15. **Escalating Threats, Assassination, and Enduring Legacy (1964-1965 and Posthumous)**The final year of Malcolm X’s life, 1964-1965, was fraught with escalating threats following his critiques of the Nation of Islam. In February 1964, a Temple Number Seven leader ordered his car bombed. Muhammad himself reportedly told Louis X that “hypocrites like Malcolm should have their heads cut off,” a sentiment graphically echoed by a Muhammad Speaks cartoon.

Federal authorities noted the danger. FBI surveillance on June 8 intercepted a call informing Betty Shabazz her husband was “as good as dead.” An FBI informant was tipped that “Malcolm X is going to be bumped off.” The Nation also sued to reclaim his New York residence; on February 14, 1965, his house was destroyed by fire, seen as deliberate intimidation.

On February 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City, Malcolm X began addressing the OAAU. A diversion in the crowd preceded a man rushing forward and shooting him with a sawed-off shotgun. Two others fired handguns. Malcolm X was pronounced dead shortly after arriving at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, at age 39, ending a prominent civil rights figure’s life.

Three Nation of Islam members were charged and received life sentences. Speculation persists regarding broader involvement from the Nation or law enforcement; two convictions were vacated in 2021, prompting further investigations. Malcolm X’s profound legacy is honored by Malcolm X Day, numerous renamed streets and schools, and the Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center at the assassination site. His posthumously published autobiography, with Alex Haley, remains a seminal text, ensuring his powerful voice for racial justice and Black empowerment resonates for generations.