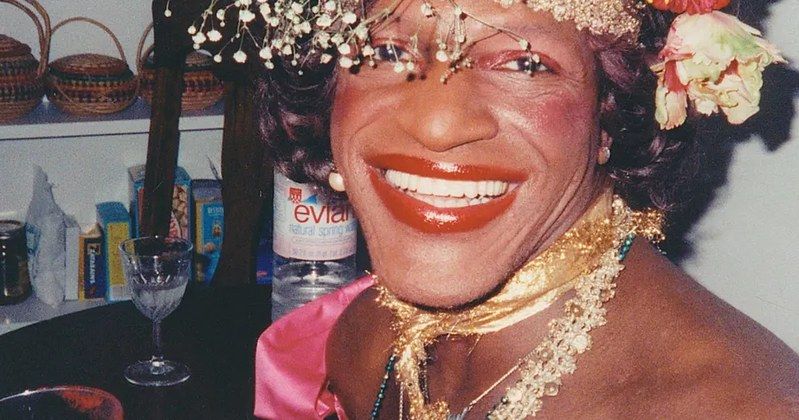

In the annals of American activism, certain figures emerge whose lives profoundly shape the trajectory of social justice movements. One such luminary is Marsha P. Johnson, an American gay liberation activist and self-identified drag queen, whose indelible mark on history continues to resonate decades after her passing.

Born Malcolm Michaels Jr. on August 24, 1945, in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Johnson’s early life was marked by experiences that would shape her unique path. She began wearing dresses at the tender age of five, an early expression of an identity that would later become central to her public persona.

However, this nascent self-expression was met with harassment, leading her to temporarily cease wearing dresses. A profoundly disturbing incident involving a thirteen-year-old boy, which Johnson described in a 1992 interview, also occurred during her youth, contributing to a complex inner landscape.

Despite these challenges, her spirit sought a different path. Johnson’s mother reportedly held a view that being homosexual was akin to being “lower than a dog,” yet she also paradoxically encouraged her daughter to seek a “homosexual billionaire” for lifelong care.

Johnson herself, at the age of sixteen and while still in high school, expressed a deep spiritual connection, stating, “I got married to Jesus Christ when I was sixteen years old, still in high school.” This profound sense of faith would remain a cornerstone throughout her life, guiding her through immense adversity.

At 17, Johnson departed for New York City, equipped with only “$15 and a bag of clothes.” She settled in Greenwich Village, initially waiting tables, but her life irrevocably shifted as she began interacting with the street hustlers near the Howard Johnson’s restaurant.

It was during this transformative period that Johnson embraced her authentic self, declaring, “my life has been built around sex and gay liberation, being a drag queen.” This self-acceptance laid the foundation for her future as an outspoken advocate for gay rights.

Her chosen drag queen name, Marsha P. Johnson, holds layers of meaning. While “Johnson” was derived from the Howard Johnson’s restaurant on 42nd Street, the “P” was humorously, yet pointedly, stated to stand for “pay it no mind,” a phrase that resonated deeply with her ethos and even amused a judge, leading to her release in one instance.

Initially, she adopted the moniker “Black Marsha” before settling on the name that would become synonymous with a movement. Johnson consistently preferred female pronouns for herself, reflecting her inner identity.

During her lifetime, the term “transgender” was not widely used, and Johnson variously described herself as gay, a transvestite, and a queen, which encompassed both drag queen and “street queen.” Susan Stryker, a professor of human gender and sexuality studies, characterized Johnson’s gender expression as gender non-conforming, a description that captures her fluid and defiant presentation.

In a 1970 interview with radio station WBAI, Johnson revealed her personal journey toward self-actualization, stating that she was undergoing feminizing hormone therapy with the aspiration of eventually undergoing gender surgery. This declaration underscored her deep commitment to her identity.

She further articulated her nuanced understanding of identity in an interview with Allen Young, published in *Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation*, where she elucidated the distinctions between a drag queen, a transvestite, and a transsexual. Johnson explained, “A drag queen is one that usually goes to a ball, and that’s the only time she gets dressed up. Transvestites live in drag. A transsexual spends most of her life in drag. I never come out of drag to go anywhere. Everywhere I go I get all dressed up. A transvestite is still like a boy, very manly looking, a feminine boy. You wear drag here and there. When you’re a transsexual, you have hormone treatments and you’re on your way to a sex change, and you never come out of female clothes.

Johnson’s personal drag style was distinctly her own, eschewing the opulent “high drag” or “show drag” due to her inability to afford expensive clothing. Instead, she became renowned for her creative and resourceful aesthetic, often adorning herself with crowns of fresh flowers, which she obtained from leftover blooms after sleeping under sorting tables in Manhattan’s Flower District.

Her appearance was striking: tall, slender, often dressed in flowing robes, shiny dresses, red plastic high heels, and vibrant wigs, which invariably drew attention. Edmund White, in his 1979 Village Voice article “The Politics of Drag,” observed that Johnson deliberately dressed in ways that highlighted “the interstice between masculine and feminine,” presenting as “both masculine and feminine at once—or male, but feminine.”

While images of Johnson in dramatic, femme ensembles are widely recognized, existing photographs and film footage also show her in more casual, daily wear such as jeans, a flannel shirt, and a cap, or shorts and a tank top without a wig, particularly at events like the Christopher Street Liberation March in 1979 or a 1992 protest.

Friends and acquaintances often characterized Marsha as generous, “warmhearted,” and even “saintly.” However, her personality was also described as “volatile” by a 1979 Village Voice article, which further noted a history of being banned from various gay bars, indicating a complex and sometimes challenging demeanor. Robert Heide recounted that she could exhibit a “schizophrenic personality” and “become a very nasty, vicious man, looking for fights.”

Johnson’s pivotal role in the Stonewall uprising of 1969 is a cornerstone of her legacy. The unrest commenced in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, and while the initial two nights were the most intense, clashes with police and spontaneous demonstrations persisted for roughly a week throughout Greenwich Village’s gay neighborhoods.

Although Johnson herself denied initiating the uprising, stating she arrived around “2:00 [that morning]” after “the riots had already started” and the Stonewall building was already “set on fire by police,” her presence was undeniably significant. David Carter, in his book *Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution*, cited Johnson, alongside Zazu Nova and Jackie Hormona, as “three individuals known to have been in the vanguard” of the resistance against police.

Accounts of her actions during the uprising vary. Robin Souza reported that fellow Stonewall veterans Morty Manford and Marty Robinson witnessed Johnson throw a shot glass at a mirror in the torched bar, exclaiming, “I got my civil rights!” Souza later famously referred to this as “the shot glass that was heard around the world.”

However, Carter noted that Robinson’s accounts of the uprising differed over time, and Johnson’s name was not always mentioned, possibly due to concerns that her known mental state and gender nonconforming identity could be exploited by opponents of the burgeoning movement. The “shot glass” incident itself has also been heavily disputed, and earlier claims of Johnson throwing a brick at a police officer remain unverified by rioters present that night.

Despite these debates, many have corroborated that on the second night of the riots, Johnson demonstrated her fierce defiance by climbing a lamppost and dropping a heavy bag onto a police car, causing the windshield to shatter. This act of direct action exemplified her unwavering commitment to fighting for justice.

Beyond Stonewall, Johnson’s activism continued with fervor. On June 28, 1970, the first anniversary of the uprising, she marched in the inaugural Gay Pride rally, then known as Christopher Street Liberation Day. In September 1970, she joined the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and became an active member of its Drag Queen Caucus, recognizing the unique power of her community’s visibility.

One of her notable direct actions occurred in the same month she joined the GLF, when she participated in a sit-in protest at Weinstein Hall at New York University. This protest was in response to administrators canceling a dance upon discovering it was sponsored by gay organizations, showcasing Johnson’s immediate response to discrimination.

Shortly thereafter, Johnson and her close friend Sylvia Rivera co-founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), initially known as Street Transvestites Actual Revolutionaries. Together, they became a highly visible and vocal presence at gay liberation marches and other radical political actions, demanding recognition and rights for their community.

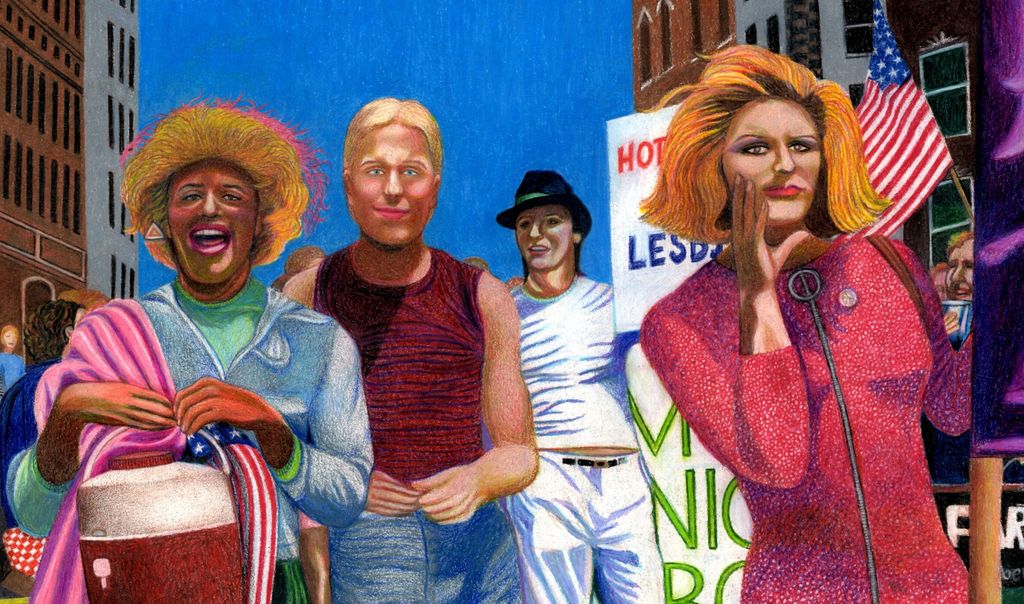

Their commitment was tested in 1973 when the gay and lesbian committee administering the gay pride parade controversially banned them from participating, asserting they “weren’t gonna allow drag queens” at their marches, claiming they were “giving them a bad name.” Johnson and Rivera’s defiant response was to march resolutely ahead of the parade, a powerful statement against exclusion from within their own movement.

During a gay rights rally at New York City Hall in the early 1970s, captured in a photograph by Diana Davies, a reporter inquired about the group’s demonstration. Johnson’s unequivocal response, shouted into the microphone, was, “Darling, I want my gay rights now!” This iconic declaration encapsulated the urgency of their demands.

In another compelling incident, Johnson was confronted by police officers for hustling in New York. When the officers attempted to arrest her, she retaliated by striking them with a handbag that contained two bricks. When asked by the judge to explain her hustling, Johnson claimed she was attempting to secure funds for a tombstone for her husband.

In a period when same-sex marriage was illegal in the United States, the judge questioned what “happened to this alleged husband.” Johnson’s audacious reply was, “Pig shot him.” Although initially sentenced to ninety days in prison for the assault, her lawyer successfully convinced the judge that Bellevue Hospital would be a more appropriate setting, highlighting the systemic challenges faced by those on the margins.

In November 1970, Johnson and Rivera embarked on a groundbreaking initiative: the establishment of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR House). This pioneering organization served as a vital shelter for homeless gay and trans youth, offering a sanctuary for those cast aside by society.

Remarkably, they financed the rent for STAR House through their own earnings as sex workers, demonstrating an extraordinary commitment to their community. Within STAR House, Johnson embraced the role of a “drag mother,” embodying the longstanding tradition of “Houses” as chosen families within the Black and Latino LGBT community.

Her role involved providing essential sustenance, clothing, emotional support, and a profound sense of family for the young drag queens, trans women, gender nonconformists, and other gay street kids who had found themselves living on the Christopher Street docks or in Johnson’s own Lower East Side residence. While the original STAR House location was evicted in 1971 and the building demolished, Johnson herself indicated that after this eviction, the group dispersed, with some members facing drug overdoses and others, including Rivera, moving away.

Johnson’s life in New York City, particularly after settling there in 1963, often meant living on the streets and engaging in survival sex. She recounted facing dangerous confrontations with customers who, upon realizing she was not a cisgender woman after she removed her clothing, would threaten her with violence, despite her assurances that she was not female.

In connection with her sex work, Johnson claimed to have been arrested over 100 times, enduring significant police harassment and a shooting incident in the late 1970s. These experiences highlight the extreme dangers and systemic oppression she faced daily.

Her life was also marked by periods of profound mental health challenges. Johnson spoke of experiencing her first mental breakdown in 1970, and by 1979, she estimated she had endured approximately eight such episodes. Bob Kohler, a friend, described instances where Johnson would walk naked up Christopher Street, leading to her being taken away for two or three months for treatment with chlorpromazine, an antipsychotic medication.

Upon her return, Kohler noted that the medication’s effects would gradually diminish over about a month, and Johnson would revert to her customary state. These accounts underscore the immense personal struggles she navigated while simultaneously fighting for the rights of others.

Between 1980 and her death in 1992, Johnson resided with her friend Randy Wicker, who had initially invited her to stay one cold night and found that she simply never left. During this period, Johnson became a devoted caregiver for Wicker’s lover, David, who became terminally ill with AIDS.

Her experiences visiting David and other friends battling the virus in hospitals during the AIDS pandemic deeply affected her. Diagnosed with AIDS herself around 1990, Johnson became passionately committed to sitting with the sick and dying, extending compassion and care to those in their most vulnerable moments.

Simultaneously, she remained an active street activist, engaging with AIDS activist groups such as ACT UP, demonstrating her relentless dedication to public health advocacy even while facing her own severe illness. David France’s documentary, *The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson*, notably features footage of Johnson participating in a 1980s memorial service for AIDS victims alongside members of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

In 1992, New York City was gripped by a severe epidemic of gay bashing, with 1,300 reported incidents, 18% of which were allegedly perpetrated by police. In response, marches were organized, and Johnson, ever the activist, bravely marched in the streets, demanding justice and accountability for the victims of this violence.

Just weeks later, Johnson herself would be found dead, having sustained a severe head injury, adding a tragic footnote to her advocacy against such brutality. Her profound insights were also evident in her comments on the installation of George Segal’s *Gay Liberation* statues in Christopher Park in 1992.

Johnson reflected, “How many people have died for these two little statues to be put in the park to recognize gay people? How many years does it take for people to see that we’re all brothers and sisters and human beings in the human race? I mean how many years does it take for people to see that we’re all in this rat race together.” Her words underscored the immense cost of progress and the enduring fight for true equality.

Throughout her later life, Johnson remained profoundly devout, frequently lighting candles and praying at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Hoboken, which was later renamed Our Lady of Grace. In 1992, she articulated her spiritual philosophy, stating, “I practice the Catholic religion because the Catholic religion is part of the Santería of the saints, which says that we are all brothers and sisters in Christ.”

She also maintained a deeply personal connection to the divine, often making offerings to saints and spirits, and keeping a private altar when circumstances allowed. As her friend James Gallagher shared in the documentary *Pay It No Mind*, “Marsha would always say she went to the Greek Church, she went to the Catholic Church, she went to the Baptist Church, she went to the Jewish Temple – she said she was covering all angles.

In the summer of 1991, Johnson participated in an interfaith AIDS memorial service at the Church of Saint Veronica in Greenwich Village, further illustrating her inclusive spiritual practice. In her final interview in June 1992, when questioned about religion, Johnson stated, “I use Jesus Christ the most in my prayers, most of the time.”

A neighbor recounted seeing Johnson pray, prostrate on the floor, before a statue of the Virgin Mary in the church across from Wicker’s apartment. Her friend Sasha McCaffrey added, “I would find her in the strangest churches. She’d be wearing velvet and throwing glitter,” capturing the unique blend of her spiritual devotion and flamboyant persona.

Johnson’s conception of her relationship with the Divine was direct and deeply personal. In her last interview in June 1992, she spoke of her move to New York City in 1963, asserting, “I got the Lord on my side, and I took him to my heart with me and I came to the city, for better or worse. And he said, ‘You know, you might wind up with nothing.’ ‘Cause you know, me and Jesus is always talking. And I said, Honey, I don’t care if I never have nothing ever till the day I die. All I want is my freedom.”

She further emphasized her trust in a higher power, stating, “I believe Jesus is the only man I can truly trust. He’s like the spirit that follows me around, you know, and helps me out in my hour of need.” This profound faith provided a bedrock of strength amidst life’s turbulence.

Johnson’s spiritual beliefs also extended to an unusual relationship with Neptune. Bob Kohler, in *Pay It No Mind*, recounted an instance where Johnson, naked, insisted on throwing Kohler’s shirt into the Hudson River, shouting, “My father needs those clothes!” Kohler explained that these acts were “sacrifices to her father, and to Neptune, who got all mixed up together.

Agosto Machado further elaborated, stating, “She was making offerings of flowers and change to King Neptune as an appeasement to help her friends who are on the other side.” These practices underscore the unique and deeply personal spiritual world Johnson inhabited.

The circumstances surrounding Marsha P. Johnson’s death remain a source of enduring controversy and sorrow. Shortly after the 1992 gay pride parade, her body was discovered floating in the Hudson River. Despite initial police rulings of suicide, her friends and members of the local community vehemently insisted that she was not suicidal, pointing to a severe wound found on the back of her head.

Her death occurred during a period of heightened anti-gay violence in New York City, including alleged hate crimes perpetrated by police. Johnson had been actively drawing attention to these issues, participating in marches and other forms of activism to demand justice for victims and an inquiry into how to curb the violence. She had also vocally criticized “dirty cops” and elements of organized crime, concerns that tragically seemed to foreshadow her own fate.

These factors fueled suspicions of foul play and possible murder among those who knew her best. Following her funeral at a local church and a march down Seventh Avenue, Johnson’s body was cremated, and her ashes were released over the Hudson River, off the Christopher Street piers, a poignant farewell to a beloved figure.

In the wake of her death, a series of demonstrations and marches to the police precinct ensued, demanding justice for Johnson and a thorough investigation into the suspicious circumstances. While Sylvia Rivera stated that Bob Kohler believed Johnson took her own life due to an increasingly fragile state, Rivera herself disputed this, asserting that she and Johnson had “made a pact” to “cross the ‘River Jordan’ together.”

Those closest to Johnson consistently maintained that while she grappled with mental health challenges, this never manifested as suicidal ideation. Randy Wicker, with whom she lived, suggested that Johnson might have hallucinated and walked into the river, or perhaps jumped in to escape harassers, but he firmly stated she was never suicidal.

Further complicating the initial ruling, several individuals came forward, claiming to have witnessed Johnson being harassed by a group of “thugs” who were also involved in robberies. According to Wicker, one witness reportedly saw a neighborhood resident fighting with Johnson on July 4, heard him use a homophobic slur, and later overheard him bragging at a bar about having killed “a drag queen named Marsha.” This witness’s attempts to report the sighting to the police were reportedly ignored.

Other local residents later stated that law enforcement at the time displayed a lack of interest in investigating Johnson’s death, characterizing the case as concerning a “gay black man” and wishing to have little involvement. However, public pressure and continued advocacy led to significant postmortem developments.

In December 2002, a police investigation resulted in the reclassification of Johnson’s cause of death from “suicide” to “undetermined,” acknowledging the persistent ambiguities. Former New York politician Thomas Duane actively campaigned to reopen the case, reasoning, “Usually when there is a death by suicide the person usually leaves a note. She didn’t leave a note.”

Then, in November 2012, activist Mariah Lopez successfully urged the police to reopen the case as a possible homicide, a crucial step toward potentially uncovering the truth. In 2016, Victoria Cruz of the Anti-Violence Project undertook her own efforts to get Johnson’s case reopened, successfully gaining access to previously unreleased documents and witness statements.

Cruz meticulously sought out new interviews with witnesses, friends, other activists, and police officers who had been involved with the case or on the force at the time of Johnson’s death. Some of her dedicated work in pursuing justice for Johnson was documented in David France’s 2017 film, *The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson*, which, like *Pay It No Mind*, relied heavily on archival footage and interviews.

Marsha P. Johnson’s profound impact has been honored through a growing number of tributes, solidifying her place as an icon of the LGBTQ+ liberation movement. The 2012 documentary *Pay It No Mind – The Life and Times of Marsha P. Johnson* extensively features segments from a 1992 interview with Johnson herself, filmed shortly before her passing, alongside interviews with many of her friends from Greenwich Village.

Her story has also been adapted into fictional film dramas based on real events, including *Stonewall* (2015), where she was portrayed by Otoja Abit, and *Happy Birthday, Marsha!* (2016), with Mya Taylor in the role. These films offer creative interpretations inspired by the pivotal Stonewall uprising.

Artist Anohni has produced multiple significant tributes to Johnson, including naming her baroque pop band “Anohni and the Johnsons” in Johnson’s honor, and creating the 1995 play *The Ascension of Marsha P. Johnson*. Furthermore, Johnson is depicted on the artwork of Anohni’s 2023 album, *My Back Was a Bridge For You to Cross*, underscoring her lasting inspiration.

Even RuPaul, the renowned American drag queen and TV personality, has publicly acknowledged Johnson’s influence, describing her as “the true Drag Mother.” In a 2012 episode of *RuPaul’s Drag Race*, RuPaul explicitly told contestants that Johnson “paved the way for all of them,” highlighting her foundational role in drag culture.

In 2018, *The New York Times* published a belated obituary for Johnson, a testament to her overdue recognition in mainstream historical narratives. The year 2019 saw the unveiling of a large, painted mural depicting Johnson and Sylvia Rivera in Dallas, Texas, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots. This painting of the “two pioneers of the gay rights movement” in front of a transgender flag is claimed to be the world’s largest mural honoring the trans community.

Further solidifying her legacy, it was announced on May 30, 2019, that Johnson and Sylvia Rivera would be honored with monuments in Greenwich Village, near the historic Stonewall club. These monuments are set to be the world’s first to specifically honor transgender activists, marking a monumental step toward recognizing their contributions.

Another artistic tribute emerged on May 31, 2019, when queer street artists Homo Riot and Suriani created a mural as part of the WorldPride Mural Project and Stonewall 50 – WorldPride NYC 2019. This mural, dedicated to Queer Liberation and featuring multiple images of Johnson, is located at 2nd Avenue and Houston Street in New York City.

In June 2019, Johnson was among the inaugural fifty American “pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes” inducted onto the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor within the Stonewall National Monument (SNM) in New York City’s Stonewall Inn. The SNM stands as the first U.S. national monument dedicated to LGBTQ rights and history, and the wall’s unveiling was purposefully timed to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, symbolizing a pivotal moment of recognition.

On June 30, 2020, Google honored Marsha P. Johnson with a dedicated Google Doodle, bringing her story to a vast global audience. In August 2020, her hometown of Elizabeth, New Jersey, received a significant announcement from the Union County Office of LGBTQ Affairs: a monument to Johnson would be erected near City Hall.

This decision followed a petition that garnered over 75,000 signatures, advocating for the removal of the Christopher Columbus monument in the city’s Italian neighborhood and its replacement with a statue of Johnson, demonstrating strong public support for her recognition. Although the mural of Johnson in Elizabeth was unfortunately vandalized during Pride Month in June 2021, community organizers swiftly vowed to fund its restoration, ensuring her legacy continues to be honored.

Perhaps one of the most significant honors came on August 24, 2020, the 75th anniversary of Johnson’s birth, when a New York state park was renamed the Marsha P. Johnson State Park. This historic renaming made it the first New York state park to be named after an openly gay person, a profound acknowledgment of her identity and impact.

Two years later, Governor Kathy Hochul announced further recognition, with plans for a new gate to the park to be constructed in Johnson’s honor, symbolizing an enduring welcome. These diverse and powerful tributes collectively speak to the immense and growing appreciation for a figure whose life was a testament to courage, resilience, and unyielding advocacy.

Marsha P. Johnson’s journey, from a young person navigating societal prejudice to a tireless activist and a beacon of hope for marginalized communities, is a story woven into the very fabric of American social progress. Her vibrant spirit, her defiant “pay it no mind” philosophy, and her relentless pursuit of freedom and dignity carved pathways for generations to come. Though her life ended tragically, the enduring questions surrounding her death serve as a potent reminder that the fight for justice, in all its forms, is never truly over. Her legacy is not merely etched in historical documents but lives vibrantly in the ongoing movements for liberation, a perpetual source of inspiration to stand tall, demand rights, and embrace one’s authentic self, no matter the cost. Her spirit, like the flowers she famously wore, continues to bloom brightly, guiding the way towards a more just and compassionate world.

Her story serves as a powerful testament to the transformative power of an individual committed to radical love and unwavering authenticity. In every monument, every mural, and every renewed call for justice, Marsha P. Johnson’s voice echoes, reminding us that true liberation demands courage, compassion, and an unshakeable belief in the inherent dignity of every human being. Her life’s work continues to inspire, illuminating the path forward for all who seek freedom and justice.