The world of jazz mourns the passing of Martial Solal, the acclaimed French pianist and composer, who died on December 12, 2024, in Versailles, France, at the age of 97. Solal, celebrated for his dextrous command of the jazz language and his pioneering spirit in European jazz, leaves behind a monumental legacy that spans nearly three-quarters of a century, marked by both profound musical innovation and a distinctive intellectual approach to his art.

His career, which began long before jazz firmly took root outside the United States, saw him emerge as Europe’s pre-eminent jazz pianist. Solal was not merely an interpreter but an eternal “researcher in jazz,” as he described himself in a 2011 interview with The Gruppen Review, constantly pushing the boundaries of improvisation and composition. His contributions extended beyond the concert hall, notably including his work as a film composer, most famously for Jean-Luc Godard’s groundbreaking 1960 debut feature, “Breathless.”

From his early life in Algiers to his final farewell concert in Paris, Solal’s journey was one of resilience, relentless practice, and an unwavering commitment to musical honesty. This article takes an in-depth look at the pivotal moments and defining characteristics of a virtuoso whose impact resonated across continents and generations, shaping the very language of jazz.

1. Formative Years and Early Musical Encounters in Algiers

Martial Solal’s extraordinary life began on August 23, 1927, in Algiers, then a French colony in Algeria. Born to Algerian Jewish parents, his musical inclinations were nurtured from a young age, with his mother, Sultana Abrami, an amateur opera singer, encouraging his studies in clarinet, saxophone, and classical piano. These early lessons laid the groundwork for a prodigious talent that would later captivate audiences worldwide.

However, his formative years were marked by adversity. In 1942, at the age of 15, Solal was expelled from school due to his Jewish ancestry, a consequence of the Vichy regime in France adopting Nazi policies that extended to its colonies. This traumatic experience forced him to continue his musical education privately, imitating the jazz he heard on the radio, demonstrating an early self-reliance and dedication to his craft.

A pivotal influence during this period was a jazz musician neighbor of his aunt, who also led a dance band. Solal recounted this teacher as “a big, fat, impressive cat who played piano, saxophone, drums, accordion, clarinet, trumpet, everything.” It was through this mentor and the recordings of artists like Benny Goodman and Fats Waller that a profound spark for jazz was ignited, leading Solal to join his teacher’s band, playing both piano and clarinet.

2. Arrival in Paris and Integration into the Postwar Jazz Scene

In 1950, seeking broader musical horizons, Martial Solal made the pivotal move to Paris. Upon his arrival, he subtly altered his public identity, dropping “Cohen” from his surname and performing exclusively as Martial Solal. This decision, as he revealed in an email interview for his obituary, was a personal measure taken due to the prevalence of antisemitism, stating he “hid myself well, for fear of losing a few friends.”

Paris in the post-war era was a vibrant hub for jazz, attracting American expatriate musicians and fostering a dynamic local scene. Solal quickly immersed himself, notably meeting Kenny Clarke, a pioneering figure in modern jazz drumming who had moved from the U.S. They soon became integral members of the house band at the renowned Club St. Germain, a venue where many visiting American jazz greats frequently performed.

It was at Club St. Germain that Solal’s career truly began to flourish. The club was also a favored haunt of Django Reinhardt, the legendary Romani guitarist, and it was with Reinhardt that Solal had his very first recording session in 1953, a significant milestone that also marked Reinhardt’s final recording. Solal’s early years in Paris saw him working alongside other eminent American expatriates such as Sidney Bechet and Don Byas, solidifying his reputation as a rising star in the burgeoning European jazz landscape. He also performed under the name Jo Jaguar and formed his own quartet in the late 1950s, having already begun recording as a leader since 1953, establishing his multifaceted presence in the city’s jazz fabric.

3. The Cinematic Breakthrough: Scoring Godard’s “Breathless”

Martial Solal’s innovative musicality found an unexpected, yet profoundly impactful, outlet in the world of cinema. His connection to film began when director Jean-Pierre Melville, impressed by an interlude Solal composed for his 1959 thriller “Deux Hommes dans Manhattan,” recommended him to the burgeoning filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard. This introduction would lead to one of the most iconic collaborations in cinematic history.

Godard commissioned Solal to compose the soundtrack for his debut feature film, “À bout de souffle” (known in the English-speaking world as “Breathless”), released in 1960. Remarkably, Godard provided minimal instruction, famously telling Solal, “Godard had no ideas about the music, so fortunately I was completely free.” Solal recounted a humorous instance where Godard suggested, “Why don’t you just write it for one banjo player?” — a proposition Solal initially thought was a joke, ultimately opting for a more ambitious score involving “a big band and 30 violins.”

The resulting soundtrack, a modern chamber-jazz score, became as revolutionary as the film itself. Critics lauded Solal’s music for perfectly capturing the mood of the French New Wave masterpiece, with reviewer Rubin Safaya noting how the “percussive and jangly bebop” emphasized the protagonist’s “improvisational, scattershot lifestyle” while “slowly ambling strings” conveyed the American girlfriend’s “carefree yet without urgency.” Solal later remarked, “I never found out if he liked it, even now, but it seems to have worked,” a modest assessment of a score that would launch both his own career and Godard’s into international acclaim.

4. Defining His “Brilliant, Unique, and Intellectual” Jazz Approach

Martial Solal’s distinct musical voice quickly set him apart in the jazz world, earning him a reputation for an approach that was both academically rigorous and exhilaratingly free. Critic Jean-Pierre Thiollet once encapsulated his style as “brilliant, unique and intellectual,” a description that aptly captured the essence of Solal’s profound engagement with the jazz idiom. His piano playing combined a formidable technical prowess with a ceaseless intellectual curiosity, allowing him to navigate complex musical ideas with apparent ease.

Critics frequently drew parallels between Solal’s technical virtuosity and that of the legendary Art Tatum, particularly marveling at the speed and clarity of his arpeggios. Yet, Solal was never content to merely imitate; while his playing might have echoed the likes of Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk, he always blazed his own path, infusing his performances with a modern sensibility. Le Monde described his style as “cutting through his music with the precision of a goldsmith,” highlighting his meticulous craftsmanship and innovative harmonic language.

Solal himself articulated the philosophy behind his technique: “You have to make people believe that it’s very easy, even when it’s very difficult. If you look to have trouble with the technique, it is no good. You must play the most difficult thing like this.” This commitment to effortless execution, combined with an abundance of sensitivity, creativity, and prodigious technique, as lauded by Duke Ellington, allowed him to apply his unique qualities across a diverse range of musical settings, from intimate combos to expansive big bands.

5. The Art of Solo Piano: Unaccompanied Virtuosity

Among the many facets of Martial Solal’s illustrious career, his solo piano work stood as a “special category,” a realm where his unparalleled virtuosity and boundless imagination truly shone. Playing without the support of a rhythm section presented the ultimate challenge, one that Solal embraced with a vibrant expressive facility that consistently elicited comparisons to the legendary uber-virtuoso Art Tatum.

Solal considered unaccompanied performance to be the most demanding. As he told John Fordham of The Guardian in 2010, “Even if I don’t play a concert for one month, or two months, I must practise so I know my fingers will follow my thoughts — otherwise it doesn’t seem honest to me.” This rigorous dedication underpinned his ability to weave intricate narratives and explore boundless improvisational pathways entirely on his own. His expansive solo discography, including historical artifacts like “Solo Piano: Unreleased 1966 Los Angeles Session” and more recent concert albums such as “Live in Ottobrunn” (2018), serves as a testament to this profound commitment.

He further explained his unique approach to solo playing in a 2007 interview: “The music you play alone is quite different from what you play with a rhythm section because you have to tell the whole story yourself. Nobody is there to help you or to disturb you. It’s a different approach.” Critics universally lauded his solo efforts, with Francis Davis of The New York Times praising him as “comparable to Art Tatum in the speed of his arpeggios but thoroughly modern in his rhythmic accents and with a sense of caprice that seems all his own,” underscoring the originality and brilliance he brought to the solo piano format.

6. Early American Recognition: The Newport ’63 Sensation

While Martial Solal was revered in Europe, his introduction to American audiences in the early 1960s marked a significant moment in his career, albeit with a touch of intriguing circumstance. His first visit to the United States came in 1963, highlighted by an appearance at the prestigious Newport Jazz Festival in Rhode Island. This debut on American soil was met with considerable anticipation, solidifying his reputation among jazz cognoscenti.

Curiously, the album purporting to be a recording of his Newport ’63 performance was later documented as a studio recreation, complete with overdubbed applause, a detail revealed in the sleeve notes of subsequent reissues. Despite this, the impact of his live presence was undeniable. Festival promoter George Wein extended Solal’s American engagement, booking him for a run at the Hickory House on West 52nd Street in New York City.

Here, Solal found himself, quite by chance, inheriting Bill Evans’s rhythm section: bassist Teddy Kotick and drummer Paul Motian. An effusive review in Time magazine, which described Solal as possessing “an imagination that is rich to the point of bursting,” quickly spread the word. The public response was overwhelming, with lines winding around the block, leading to the gig being extended from an initial short run to an impressive ten weeks. This early American recognition was further cemented by luminaries like Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie, who provided glowing blurbs for the cover of Solal’s RCA Victor album “At Newport ‘63,” with Ellington appraising Solal as having, “in abundance, those indispensables of the musicians’ craft: sensitivity, creativity, and a prodigious technique.” His initial forays into the American jazz scene, though limited, left an indelible mark.”

7. Extensive Collaborations: A Confluence of Jazz Minds

Martial Solal’s illustrious career was not defined by solo brilliance alone; it was also enriched by an extensive array of collaborations that spanned continents and generations, invariably keeping his musical partners “on their toes.” His ability to seamlessly integrate his complex ideas with those of others spoke volumes about his versatility and deeply interactive spirit as a musician. He frequently enlisted accomplished European colleagues such as the Danish bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen and French drummer Daniel Humair, forming formidable trios and duos that pushed the boundaries of jazz.

Beyond his European compatriots, Solal sought out and was embraced by eminent American collaborators. Bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Paul Motian, for instance, supported and challenged him in equal measure on the standout 1997 trio release, *Just Friends*. These partnerships were not merely about accompaniment; they were dynamic dialogues where Solal’s inventive energy met equally potent musical minds, creating a synergistic exchange that elevated every performance.

The duo setting, in particular, became a fertile ground for some of his most celebrated tête-à-têtes. Among these are his acclaimed albums with alto saxophonist Lee Konitz, with whom he performed and recorded in both Europe and the U.S. from 1968, and tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin. In his later years, Solal continued this tradition, notably recording in concert with American tenor and soprano saxophonist Dave Liebman in 2016, yielding the fine albums *Masters in Bordeaux* and *Masters in Paris*. These recordings stand as a testament to his enduring ability to connect and create with diverse musical personalities, even occasionally setting up opposite a fellow pianist, such as Joachim Kühn in the mid-1970s and Tigran Hamasyan at a French jazz festival in 2011.

8. Beyond the Trio: Orchestral Ambitions and Big Band Leadership

While Solal was often celebrated for his intimate solo and trio performances, his musical imagination extended far beyond these settings to embrace grander, more ambitious projects. He was not only a virtuoso pianist but also a prolific and versatile composer, whose works included pieces for big bands and even symphonies. His scores for numerous films, though never his primary occupation, demonstrated his profound understanding of how music could shape narrative and mood.

Following the international acclaim for his work on Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless,” Solal was in demand from other directors, composing for more than a dozen films. These included Jean Cocteau’s “Testament of Orpheus” (1960), the art-house romp “The Flamboyant Sex” (1963), and the French crime film “Backfire” (1964), which notably reunited the “Breathless” stars Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg. His final film score, for Bertrand Blier’s “Les Acteurs,” came as recently as 2000, showcasing a compositional career that spanned decades.

His compositional prowess also found expression in large-ensemble works. Solal led a 12-piece ensemble he affectionately called his “dodecaband,” demonstrating his command of complex arrangements and his ability to inject his distinctive voice into broader orchestral textures. Albums like “Martial Solal Dodecaband Plays Ellington” (2001) exemplify this facet of his work, offering fresh, analytical perspectives on classic material. Moreover, his ambitious scope extended to classical forms, with his having written “four concertos for piano and orchestra,” underlining his comprehensive mastery as a composer who effortlessly bridged jazz improvisation with the disciplined structures of classical composition.

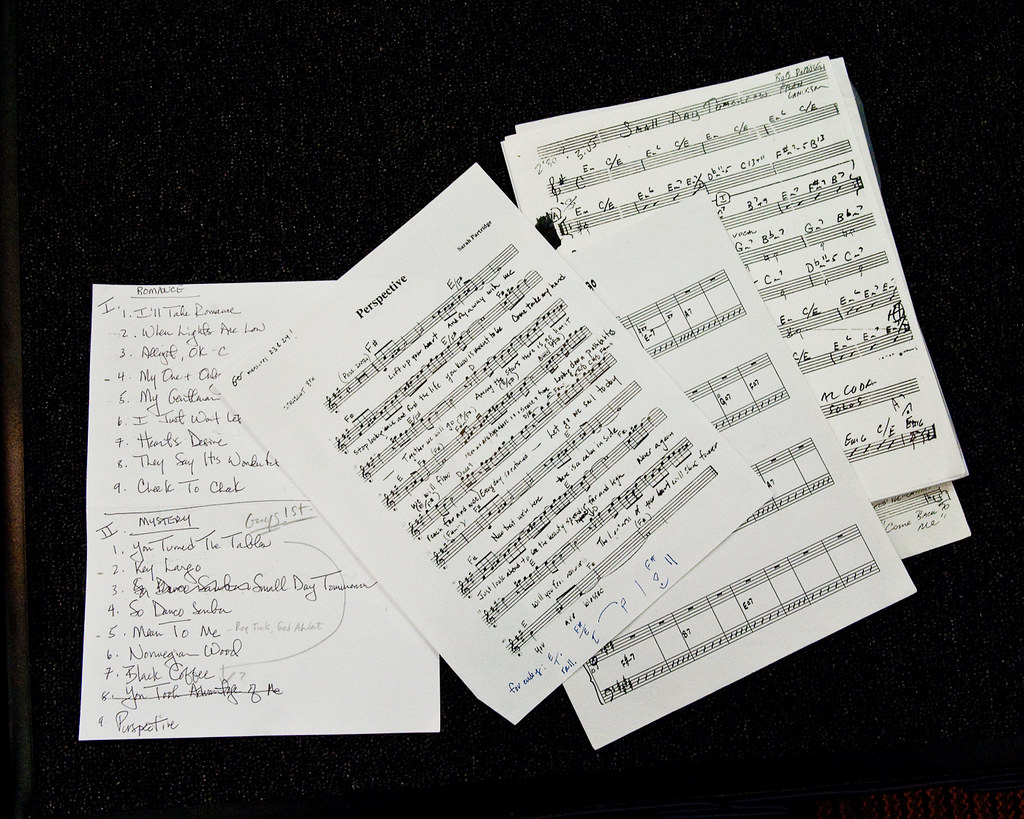

9. A Vast Discography: Decades of Recording Innovation

Martial Solal’s “startlingly original albums” trace a remarkable artistic journey spanning “almost three quarters of a century,” forming a discography that is as vast as it is diverse. His commitment to recording began early, with his first session in 1953 with Django Reinhardt, and continued relentlessly throughout his life, reflecting his tireless pursuit of musical exploration and documentation. From early releases like *French Modern Sounds* and *Martial Solal Trio*, both from 1954, he established himself as a recording artist committed to capturing his evolving musical ideas.

His recorded output showcased his adaptability across various formats, from solo piano, which he considered a “special category,” to intimate duos and trios, and larger big band configurations. Albums such as *Himself* (1974) and *Jazz ‘n (E)motion* (1998) highlight the longevity and continuous innovation of his solo and small-group work. Even late in his career, he continued to release significant recordings, including the solo concert albums like *Live in Ottobrunn*, recorded in 2018, and *Coming Yesterday: Live at Salle Gaveau 2019*.

The sheer volume and consistent quality of his recordings solidified his reputation not just as a performer, but as a chronicler of his own musical evolution and a significant contributor to the jazz canon. Whether reinterpreting standards with deeply original arrangements, as seen in “Martial Solal Dodecaband Plays Ellington,” or venturing into entirely new compositions, Solal’s discography offers a profound insight into a musician who never ceased creating, innovating, and sharing his unique musical vision with the world, making each album a testament to his “cutting through his music with the precision of a goldsmith.”

10. The Philosophy of an “Eternal Researcher”: Improvisation as Discovery

Martial Solal famously described himself as an “eternal ‘researcher in jazz'” in a 2011 interview with The Gruppen Review, a designation that profoundly encapsulates his intellectual and artistic philosophy. This approach infused his piano playing with a “regal yet inquisitive style,” characterized by “whimsical digression with a firm intellectual footing.” For Solal, improvisation was not merely spontaneous invention but a rigorous intellectual pursuit, a constant discovery within the framework of musical logic and expressive possibility.

His technique, while often compared to the legendary Art Tatum for its speed and clarity, was rooted in a philosophy of effortless presentation. “You have to make people believe that it’s very easy, even when it’s very difficult,” he explained. “If you look to have trouble with the technique, it is no good. You must play the most difficult thing like this.” This commitment to making the profoundly complex appear simple was a cornerstone of his artistic integrity, ensuring that the listener’s focus remained on the musical content rather than the technical struggle.

Solal also preferred to give listeners “a point of reference,” a guiding thread through his often-dense improvisations. “I don’t like the idea of anything goes,” he told Musician magazine in 1989. “That’s why I play jazz standards, which give the audience something they can follow more easily and which will perhaps entertain them while having to put up with my, shall we say, busy style.” This self-aware approach reveals a profound respect for his audience, allowing them entry into his intricate musical world while challenging their expectations. He believed his music required “several times” listening “because of its density,” a candid acknowledgment of the intellectual depth and layered complexity he imbued into every performance.

11. Global Acclaim and Enduring Legacy: Awards and Critical Homage

Throughout his long and distinguished career, Martial Solal garnered significant global acclaim, cementing his status as one of jazz’s most revered figures. While initially “little known in the United States,” as observed by Francis Davis in The New York Times, his reputation grew to the point where he was considered “at least the equal of any in the United States.” He was a recipient of the prestigious Jazzpar Prize in 1999, an honor that acknowledged his profound contributions to jazz, and was also nominated twice for a Grammy Award, further solidifying his international recognition.

The sheer awe Solal inspired among both listeners and collaborators speaks volumes about his impact. Legends like Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie provided glowing blurbs for his albums, with Ellington famously appraising Solal as possessing “in abundance, those indispensables of the musicians’ craft: sensitivity, creativity, and a prodigious technique.” Critics consistently lauded his unique voice; John Fordham, chief jazz critic of The Guardian, called him “France’s most famous living jazz artist,” while Jean-Pierre Thiollet described his approach as “brilliant, unique and intellectual.”

His influence extended to younger generations of musicians, who held him in the highest esteem. American pianist Kenny Werner, for instance, concurred with the comparisons to Art Tatum’s technique but emphasized, “It’s his ideas that make him virtuosic, not the opposite. There is no effect with him but the music. He’s one of my heroes.” This sentiment underscores Solal’s lasting legacy: not merely as a technical marvel, but as an innovator whose intellectual rigor and boundless creativity forged a distinct, influential path within the global jazz landscape, proving that jazz transcends geographical boundaries.

Read more about: Gene Kelly’s Final Curtain: A Deep Dive into His Later Years, Private Choices, and Enduring Legacy

12. The Grand Finale: A Poignant Farewell at Salle Gaveau

Martial Solal’s extraordinary career culminated in a deeply poignant farewell concert at the landmark Salle Gaveau concert hall in Paris in 2019, where he graced the stage at the remarkable age of 91. This performance, captured on the album *Coming Yesterday: Live at Salle Gaveau 2019*, served as a magnificent bookend to a life dedicated to music, echoing his first concert on the same stage back in 1962. It was not just a concert, but “a rare feast of intelligence, senses and history,” as acclaimed by jazz critic Francis Marmande in Le Monde.

Alone on the stage, Solal embarked on a musical tour of his long career, enchanting the audience with jazzy renditions of “indestructible standards” like “Frère Jacques,” Duke Ellington’s “Sophisticated Lady,” and “Tea for Two,” even incorporating a bit of Beethoven. This final public performance was a testament to his enduring agility and imagination, demonstrating that “being 80 has not dimmed his agility or his imagination,” as Ben Ratliff noted about a previous Village Vanguard appearance. He interpreted each passing moment as a provocation, spinning new structures at breathtaking speed.

As the concert drew to a close, Solal addressed his audience with characteristic modesty and profound honesty. “Thank you. I think I’ve told you everything. I do have a couple more tunes, but I’ll hold them back for next time – I don’t want to bore you, it’s better that you leave here serene.” He then offered his final, touching words as he left the public stage for the last time: “When energy is no longer available, it is better to stop.” Placing his fingers on the keyboard for one last public gesture, he played a final chord in F major, then added, “Voilà, merci,” and exited, leaving an indelible mark on those fortunate enough to witness his grand finale. His parting sentiment reflected a life of unwavering dedication to musical truth, concluding a career that was as intellectually rigorous as it was creatively boundless.

Martial Solal’s departure leaves an irreplaceable void in the global jazz community, yet his legacy resonates with undiminished vitality. From the vibrant Parisian clubs to the hallowed stages of international festivals, from groundbreaking film scores to the intricate narratives spun from a solo piano, Solal consistently demonstrated that jazz, in its purest form, is an act of perpetual discovery. His unique blend of rigorous technique, intellectual curiosity, and an unwavering commitment to musical honesty didn’t just entertain; it educated, challenged, and ultimately expanded the very definition of what jazz could be. He was not merely a pianist but a profound thinker, a composer of immense range, and an “eternal researcher” whose influence will continue to inspire generations, ensuring that his extraordinary journey and brilliant insights remain a vibrant part of jazz’s ongoing story.