In the vast, intricate landscape of human belief and social organization, few terms ignite as much debate and misunderstanding as ‘cult.’ Far from being a simple label, it represents a complex constellation of social dynamics, ideological frameworks, and often, profound human experiences. Like dissecting a finely tuned engine, understanding these phenomena requires a precise, authoritative approach, delving into their historical evolution, sociological classifications, and the very real impact they have on individuals and societies. This is not merely an exercise in academic curiosity; it is about equipping future generations with the analytical tools to navigate a world where such groups, in various forms, continue to emerge and shape narratives.

Indeed, the concept of a ‘cult’ has a rich and often contentious history, evolving significantly from its ancient origins to its modern, often pejorative, usage. Just as classic automotive designs offer timeless lessons in engineering and aesthetics, the enduring ‘models’—be they theoretical frameworks, identifiable characteristics, or historical archetypes—of these social groups provide critical insights. These are the intellectual ‘mechanics’ that allow us to move beyond sensationalism and towards a nuanced comprehension of group behavior, influence, and devotion.

Our journey will meticulously unpack these foundational concepts, much like a master technician meticulously examines the blueprints of a classic machine. We will explore the shifting definitions, the pioneering sociological studies, and the critical differentiations that illuminate the underlying structures of groups often labeled as cults. By understanding these enduring models, we are not just accumulating knowledge; we are fostering a deeper appreciation for the complexities of human social interaction and the enduring lessons embedded within these often-controversial phenomena, insights truly worth handing down.

1. **The Evolving Lexicon of “Cult”: From Worship to Pejorative Label**

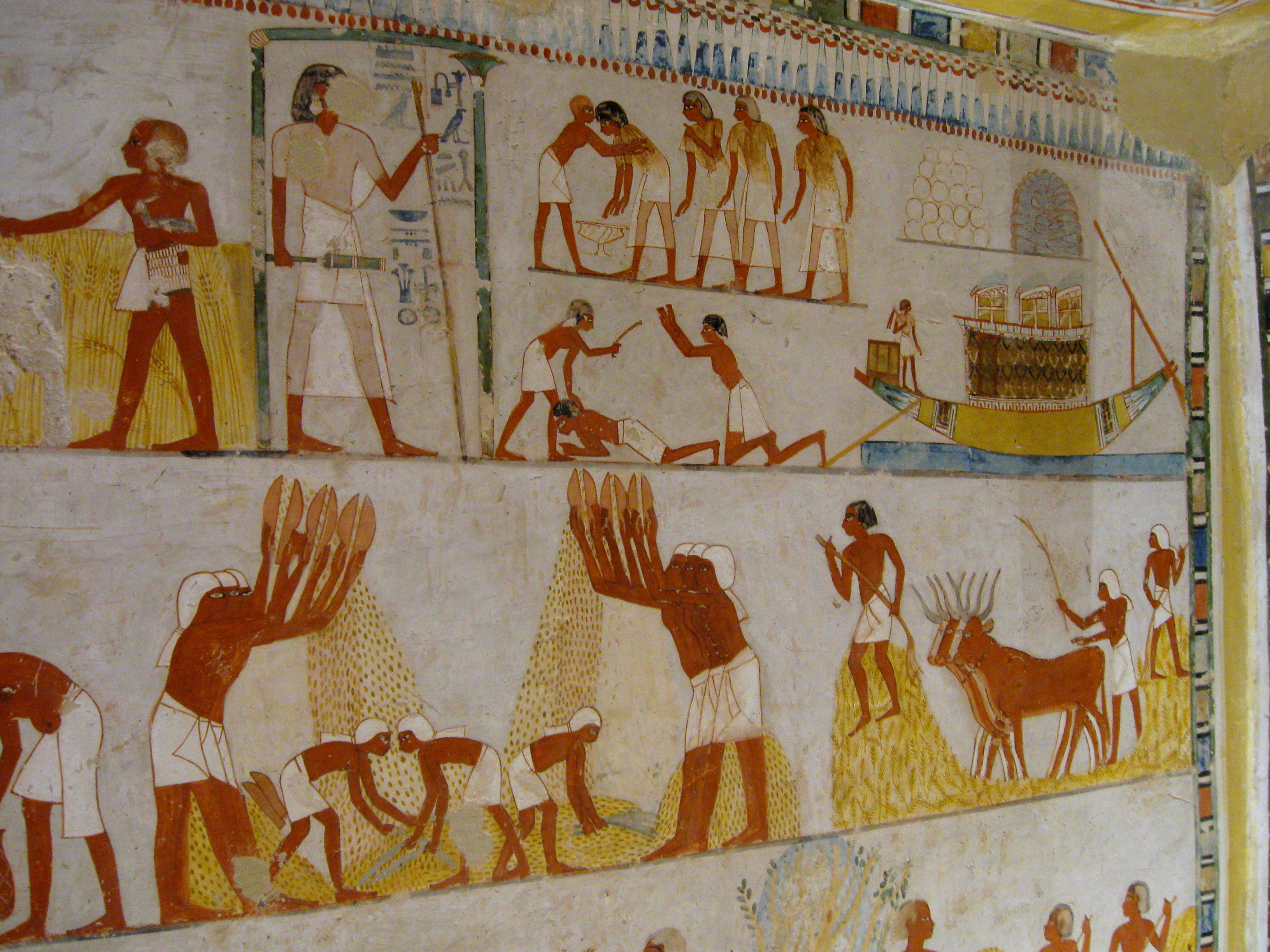

The word “cult” itself offers a fascinating case study in semantic evolution, demonstrating how a term can transform dramatically over centuries. Its etymological roots trace back to the Latin term *cultus*, which simply means ‘worship.’ In its older, non-pejorative sense, the word merely indicated “a set of religious devotional practices that is conventional within its culture, is related to a particular figure, and is frequently associated with a particular place, or generally the collective participation in rites of religion.” A prime example is references to the imperial cult of ancient Rome, where the word was used without any negative connotations, describing an accepted part of the societal and religious fabric.

However, the 19th century witnessed a significant shift in usage, giving rise to a derived sense of “excessive devotion.” This marked the beginning of the term’s journey toward its modern, often highly charged meaning. Today, in modern English, “the term cult is generally a pejorative, carrying derogatory connotations.” It has become a “shapeshifter,” as Susannah Crockford notes, “semantically morphing with the intentions of whoever uses it.”

This modern application is “variously applied to abusive or coercive groups of many categories, including gangs, organized crime, and terrorist organizations.” It has become shorthand for social groups perceived to have “unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals.” Understanding this linguistic trajectory is crucial; it highlights that the term itself is not a static, objective descriptor, but rather a dynamic cultural construct, shaped by history, perception, and often, an inherent bias.

2. **Sociological Origins: Weber, Troeltsch, and the Church-Sect Typology**

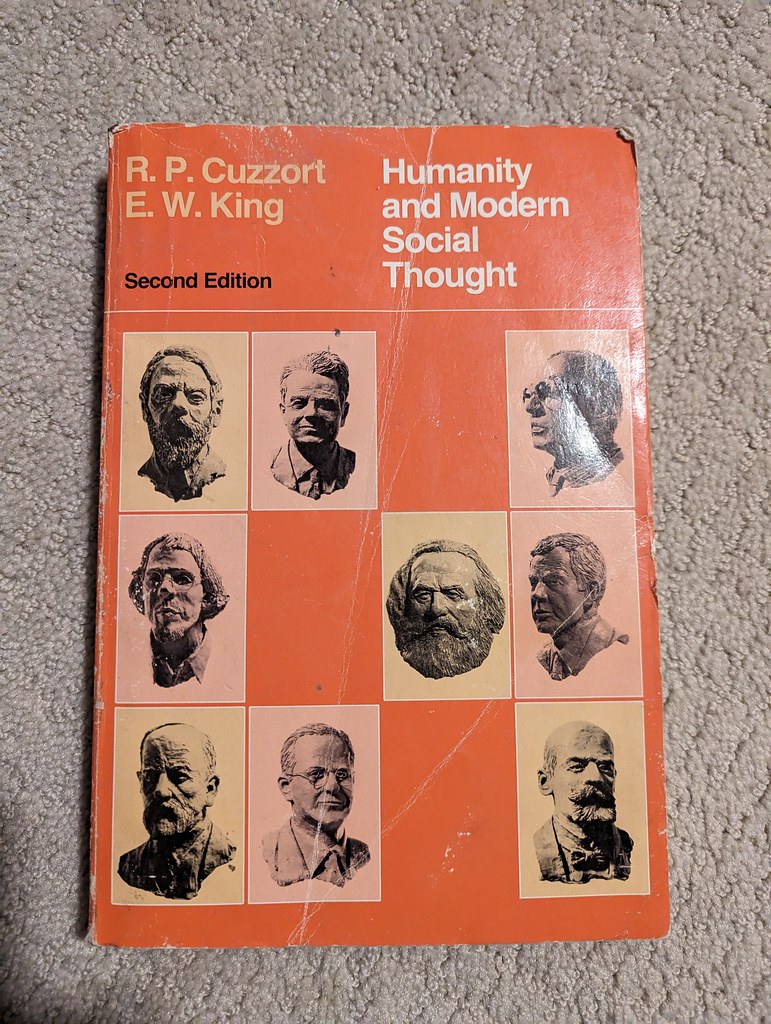

To truly grasp the academic ‘mechanics’ of understanding such groups, one must first engage with the pioneering work of early sociologists. The academic study of what were perceived as cults began in the 1930s, specifically within the context of analyzing religious behavior. Central to this foundational work is Max Weber (1864–1920), an “important theorist in the academic study of cults.” Weber’s enduring contributions include his “theorizations of charismatic authority” and, crucially, the “distinction he drew between churches and sects.”

Building upon Weber’s seminal ideas, German theologian Ernst Troeltsch further elaborated on this church–sect division. Troeltsch refined the typology by introducing a third, distinct category: “mystical.” This addition was designed “to accommodate more personal or individual religious experiences,” recognizing that not all religious expressions fit neatly into the established, more institutionalized structures of churches or the often protest-oriented nature of sects. This tri-partite model provided a more comprehensive lens through which to view the diverse landscape of religious phenomena.

Together, Weber and Troeltsch laid down the intellectual infrastructure for the systematic sociological study of religious movements. Their typologies were not merely descriptive; they offered an analytical framework that allowed scholars to categorize, compare, and understand the various ways religious groups emerge, organize, and interact with the broader society. This foundational work remains a critical reference point, an indispensable ‘blueprint’ for anyone seeking to navigate the intricate world of religious sociology and the nuanced definitions that define its study.

3. **Becker’s Refinement: Expanding the Categorization of Religious Groups**

The foundational work of Weber and Troeltsch provided a robust starting point, but the field of sociology continued to evolve, demanding finer distinctions and more granular analytical tools. American sociologist Howard P. Becker answered this call by further dissecting Troeltsch’s initial two categories, demonstrating the dynamic and often fluid nature of religious organization. His contribution effectively expanded the typology, offering a more precise ‘calibration’ for understanding diverse religious expressions.

Becker’s refinement involved splitting the “church” category into “ecclesia” and “denomination,” acknowledging the different levels of integration and universality within mainstream religious institutions. More critically, he also bisected the “sect” category into “sect” and “cult.” This move was significant because it provided a distinct sociological definition for “cult” that differed from the popular, pejorative understanding.

In Becker’s framework, analogous to Troeltsch’s “mystical religion,” his “cult refers to small religious groups that lack organization and that emphasize the private nature of personal beliefs.” This academic definition contrasts sharply with the later, more negative connotations that became prevalent in popular culture. Becker’s work thus represents a crucial step in formalizing the academic study of these groups, offering a conceptual ‘chassis’ upon which further, more detailed investigations could be built, enabling a more nuanced appreciation of their internal structures and devotional practices.

4. **The Bainbridge-Stark Typology: Dissecting Cult Structures**

As sociological understanding deepened, the need for more granular classifications of cults became apparent, moving beyond general definitions to categorize their operational structures and how they engage with their adherents. Scholars William Sims Bainbridge and Rodney Stark contributed significantly to this effort, proposing a typology that distinguishes between three distinct kinds of cults. This framework provides an invaluable ‘diagnostic tool’ for analyzing the varied manifestations of these groups, much like categorizing different vehicle classes based on their design and function.

Their typology introduces “cult movements,” which are described as “an actual complete organization.” These differ from a “sect” in a crucial way: a cult movement “is not a splinter of a bigger religion” but rather originates independently, forming its own unique belief system and structure. This distinction is vital for understanding the genesis of new religious phenomena that do not arise from schism within existing faiths.

Beyond organized movements, Bainbridge and Stark also identified “audience cults” and “client cults.” “Audience cults” are characterized by being “loosely organized” and primarily “propagated through media,” often attracting followers who consume their content without deep, direct involvement. In contrast, “client cults” are defined by offering “services (i.e. psychic readings or meditation sessions),” suggesting a transactional relationship between the group and its participants. The flexibility of this model is further highlighted by the observation that “one type can turn into another,” citing the Church of Scientology as an example of an entity “changing from audience to client cult.” While Bainbridge later expressed regret for using the word “cult,” their typology remains a powerful analytical framework, offering detailed insights into how these social groups operate.

5. **The Rise of New Religious Movements (NRMs) and the Academic Shift**

The sociological discourse surrounding groups often labeled ‘cults’ underwent a significant transformation in the latter half of the 20th century. Beginning in the 1970s, “scholars (though not the general public) began to abandon the use of the term cult, regarding it as pejorative.” This shift reflected a growing academic consensus that the term had become too loaded with negative connotations and lacked the necessary “scholarly rigour” for objective study, much like a precision instrument needing recalibration.

By the end of the 1970s, the term “cult” was largely replaced in academia with more neutral and descriptive terminology, primarily “new religion” or “new religious movement” (NRM). Other proposed alternatives included “emergent religion,” “alternative religious movement,” or “marginal religious movement,” though NRM became the most popular. This change was a direct response to a “wave of nontraditional religiosity” that surged in the late 1960s and early 1970s, which academics recognized as distinct phenomena from earlier religious innovations.

This academic reclassification was not universally accepted, particularly by the secular anti-cult movement. This movement largely “regards the term ‘new religious movement’ as a euphemism for ‘cult’ that loses the implication that they are harmful.” This tension between academic neutrality and public concern underscores the enduring challenge in discussing these groups responsibly. The shift to NRM reflects a crucial lesson in academic methodology: the importance of precise, non-judgmental language to foster objective understanding, ensuring that our analytical ‘engines’ run on facts, not prejudice.

6. **The Charismatic Leader: A Defining Feature of Many Cults**

Across many sociological and popular conceptions of cults, one figure consistently emerges as a central, often indispensable, element: the charismatic leader. This concept, deeply rooted in Max Weber’s foundational theories of authority, highlights a dynamic of power and influence that can be both captivating and, at times, deeply problematic. Understanding the role of the charismatic leader is akin to identifying the core processor within a complex system; it dictates much of the group’s operation and direction.

Such groups are “typically described as being led by a charismatic leader who tightly controls its members.” This control often extends beyond mere guidance, shaping the beliefs, behaviors, and even the daily lives of adherents. The leader’s charisma—a compelling charm or magnetism—allows them to command “excessive devotion to some person, idea, or thing,” as described by Collins and Porras in their study of “cult-like” characteristics in visionary companies.

This intense loyalty and centralized control often lead to cults being “compared to miniature totalitarian political systems.” The leader’s vision, often expressed as a “fervently held ideology,” becomes the absolute truth for the group, with processes of “indoctrination” and a demand for “tightness of fit” among members. This dynamic, characterized by a single, powerful individual exerting profound influence, is a recurring ‘component’ in the study of cults, underscoring the critical examination required when assessing groups with such centralized authority structures.

7. **Destructive Cults: Understanding Harm and Exploitation**

While academic discourse moved towards the more neutral ‘New Religious Movements,’ the secular anti-cult movement, and segments of the general public, focused on a specific, alarming category: ‘destructive cults.’ This term is predominantly used by anti-cult groups to identify organizations perceived as actively harmful. For them, a “destructive cult” is defined as “a group that is unethical, deceptive, and one that uses ‘strong influence’ or mind control techniques to affect critical thinking skills.” This distinction highlights a crucial ethical concern, much like identifying a design flaw that leads to catastrophic failure.

Psychologist Michael Langone, executive director of the anti-cult group International Cultic Studies Association, provides a succinct and impactful definition: a “destructive cult” is “a highly manipulative group which exploits and sometimes physically and/or psychologically damages members and recruits.” This definition foregrounds the manipulative and exploitative aspects, pointing to tangible harm inflicted upon individuals. Eli Shapiro, cited in *Cults and the Family*, further elaborates on this, defining “destructive cultism as a sociopathic syndrome” characterized by “behavioral and personality changes, loss of personal identity, cessation of scholastic activities, estrangement from family, disinterest in society and pronounced mental control and enslavement by cult leaders.”

However, it is crucial to note that the term ‘destructive cult’ itself has faced criticism from some researchers. John A. Saliba, in *Understanding New Religious Movements*, writes that the term is “overgeneralized.” He argues that when the Peoples Temple is presented as the “paradigm of a destructive cult,” it carries the implicit and potentially inaccurate implication “that other groups will also commit mass suicide.” This highlights the ongoing tension between cautionary labeling and the need for nuanced, evidence-based analysis, a balance that is essential in any comprehensive study of social phenomena.

Navigating the intricate landscape of social groups categorized as ‘cults’ requires more than just historical context and academic definitions; it demands a keen understanding of their diverse manifestations and the societal responses they provoke. Just as examining a classic car reveals the nuances of its design and engineering, dissecting these specific ‘models’ of cults—from those predicting global catastrophe to those focused on political agendas, and the varied reactions from anti-cult movements and governments—offers crucial insights. This section extends our authoritative exploration, moving from the theoretical blueprints to the practical applications and profound impacts of these phenomena. We meticulously explore how different types of cults operate and how societies, driven by concern and legal frameworks, have sought to understand and regulate them, ensuring that the lessons learned from these complex interactions are preserved and passed down.

Read more about: The Dark Psychology of Influence: Unmasking How Cult Leaders Employ Mind Control

8. **Doomsday Cults: Prophecy and Cataclysm**

Among the various categorizations of cults, ‘doomsday cults’ stand out for their intense focus on apocalyptic and millenarian beliefs. This specific type of group is characterized by its deep conviction in impending catastrophic events, which can manifest in two distinct ways: either by predicting the arrival of disaster or, more alarmingly, by actively attempting to bring it about. Such groups often command an unyielding devotion, fueled by the gravitas of their prophecies and the perceived urgency of their message.

A fascinating early study of this phenomenon was conducted in the 1950s by American social psychologist Leon Festinger and his colleagues. They immersed themselves within a small UFO religion known as the Seekers, observing members over several months. Their meticulous recordings of conversations, both before and after a pivotal failed prophecy from the group’s charismatic leader, provided groundbreaking insights into cognitive dissonance and belief maintenance, which were later published in the seminal work, *When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World*.

While Festinger’s work provided academic groundwork, doomsday cults surged into public consciousness again in the late 1980s. News reports and commentators frequently cast them as a serious threat to societal stability, sparking widespread concern. A later 1997 psychological study by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter illuminated the underlying motivations, finding that individuals often gravitate towards a cataclysmic worldview when they have repeatedly struggled to find meaning or fulfillment within mainstream societal movements, suggesting a deeper psychological resonance to these extreme beliefs.

9. **Political Cults: Ideology and Action**

Moving beyond the spiritual and apocalyptic, another distinct category surfaces: the ‘political cult.’ These groups shift their primary focus from religious or spiritual salvation to political action and ideology, often advocating for far-left or far-right agendas. While their ultimate goals differ from traditional religious cults, the underlying dynamics of extreme devotion and centralized control often bear striking similarities, transforming political movements into entities that demand unquestioning loyalty from their members.

Such groups have garnered considerable attention from both journalists and scholars due to their intense ideological fervor and methods. In their comprehensive 2000 book, *On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left*, Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth meticulously examined approximately a dozen organizations across the United States and Great Britain. They explicitly characterized these groups as cults, highlighting the shared characteristics of fervent ideology and an almost cult-like environment, even in a non-religious context.

This analysis underscores that the ‘cult-like’ characteristics of “excessive devotion to some person, idea, or thing” are not exclusive to religious contexts. Whether driven by a messianic political figure or an unshakeable ideological dogma, these groups demonstrate how extreme commitment and centralized control can shape social dynamics, echoing the traits seen in other forms of cultic organizations and demanding similar scrutiny of their structures and influence.

Read more about: The Dark Psychology of Influence: Unmasking How Cult Leaders Employ Mind Control

10. **The Christian Countercult Movement: Theological Opposition**

The emergence of groups labeled as cults was met with organized opposition, particularly from within established religious traditions. In the 1940s, a long-held stance by some Christian denominations against non-Christian religions, alongside groups they deemed ‘heretical’ or ‘counterfeit Christian sects,’ coalesced into a more formalized Christian countercult movement in the United States. This movement served as an early, religiously motivated response to perceived threats to orthodox faith.

For adherents of this movement, the definition of a cult was explicitly theological: any religious group that claimed to be Christian but whose teachings were deemed outside of Christian orthodoxy was labeled a cult. Primarily composed of evangelical Protestants, this countercult movement asserted that any Christian groups deviating from the belief in biblical inerrancy were problematic. Moreover, their focus extended to non-Christian religions, such as Hinduism, which they also categorized within their countercult framework.

A core tenet of Christian countercult activist writers was the profound emphasis on the need for Christians to evangelize to followers of these perceived cults. This wasn’t merely about intellectual critique; it was an active mission to reclaim individuals from groups they believed propagated false teachings. This movement, therefore, represents a significant historical ‘model’ of organized religious response, driven by theological convictions and a deep concern for spiritual adherence and doctrinal purity.

11. **The Secular Anti-Cult Movement: Brainwashing and Deprogramming**

As the 1960s and 1970s saw a surge in new religions, a distinctly different and secular strand of opposition emerged, forming the secular anti-cult movement (ACM). This movement arose not from theological concerns, but largely in response to the growing visibility of these new groups and, crucially, in the wake of tragic events such as the Jonestown deaths, which claimed nearly 1000 lives. The ACM quickly became a vocal advocate for relatives of ‘cult’ converts who believed their loved ones could not have undergone such drastic life changes willingly.

The central, unifying theme that galvanized critics within the ACM was the controversial theory of ‘brainwashing.’ A few psychologists and sociologists affiliated with the movement suggested that cults employed coercive ‘mind control’ techniques to maintain their members’ loyalty and suppress critical thinking skills. This theory, though later widely debated and largely abandoned in mainstream academia, gained considerable traction in popular culture, reshaping public perception of these groups.

In the more extreme corners of the anti-cult movement, the belief in brainwashing led to the controversial practice of ‘deprogramming.’ This often forceful intervention aimed to “reverse” the alleged brainwashing, sometimes through methods that themselves drew accusations of coercion. In the mass media and among the general public, the term ‘cult’ acquired an increasingly negative connotation, becoming associated with a litany of ills: kidnapping, psychological abuse, ual abuse, and even mass suicide.

While it is important to acknowledge that some of these negative qualities, such as documented instances of violence or criminal activity, did have real precedents in a small minority of new religious groups, mass culture often indiscriminately applied these extreme characteristics to any group viewed as culturally deviant, regardless of its actual peaceful or law-abiding nature. This highlights the profound impact of the brainwashing narrative on both public discourse and the strategies employed by the anti-cult movement, shaping a powerful, if sometimes overgeneralized, societal response.

12. **Governmental Responses: Policy and Controversy**

The contentious nature of cults and new religious movements has inevitably led to engagement at the governmental level, transforming academic and public debates into matters of public policy. The application of labels such as ‘cult’ or ‘sect’ in government documents, particularly in Europe where terms like ‘sekten’ or ‘sectes’ carry similar derogatory connotations, signifies the adoption of this negative popular usage into official discourse. This can have significant implications, as sociologists critical of this politicized labeling argue it may adversely impact the religious freedoms of group members, creating a climate of suspicion and potential discrimination.

At the height of the counter-cult movement and a wave of ritual abuse scares in the 1990s, some governments, driven by public concern and often influenced by anti-cult narratives, went so far as to publish official lists of cults. These documents, while utilizing similar terminology, were often inconsistent in their assessments, neither including the same groups nor basing their judgments on agreed-upon criteria. This lack of standardization underscored the challenge of objectively classifying religious groups and the subjective nature of the term itself.

However, a shift has been observed since the 2000s, with some governments distancing themselves from such rigid classifications of religious movements, reflecting a growing awareness of the complexities involved and the potential for mischaracterization. While the official response to new religious groups has been decidedly mixed across the globe, some governments have historically aligned more closely with critics, drawing a distinction between what they considered ‘legitimate’ religion and ‘dangerous,’ ‘unwanted’ cults in their public policy. This nuanced approach acknowledges the ongoing tension between safeguarding public welfare and upholding principles of religious freedom, a delicate balance in the governance of belief systems.

13. **Global Case Studies: China, Russia, and the U.S.**

Examining specific national contexts reveals the varied ways governments interpret and respond to groups they label as cults, showcasing how deeply cultural, political, and legal frameworks influence official actions. In China, for centuries, governments have categorized certain religions as *xiéjiào* (邪教), translated as ‘evil cults’ or ‘heterodox teachings.’ This classification historically applied to religious groups not authorized by the state or those believed to challenge state legitimacy, rather than necessarily signifying false teachings. Groups branded *xiéjiào*, such as Falun Gong—an ultra-conservative new religious movement—face severe suppression and punishment from authorities, illustrating a highly centralized and controlling approach to religious expression.

Russia’s approach, particularly in the late 2000s, also highlights governmental concern over non-traditional religious groups. In 2008, the Russian Interior Ministry compiled a list of ‘extremist groups,’ prominently featuring Islamic groups outside ‘traditional Islam’ (which is state-supervised), followed by ‘Pagan cults.’ By 2009, the Russian Ministry of Justice’s ‘Council of Experts Conducting State Religious Studies Expert Analysis’ listed 80 large sects, including The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Jehovah’s Witnesses, alongside ‘neo-Pentecostals,’ as potentially dangerous to Russian society, alongside thousands of smaller ones. This demonstrates a broad categorization based on perceived societal risk and national security interests.

In stark contrast, the United States has navigated these issues through its robust legal framework protecting religious freedom. In the 1970s, the scientific status of ‘brainwashing theory’ became a contentious topic in U.S. court cases, particularly when used to justify forceful deprogramming. Sociologists critical of these theories often assisted advocates for religious freedom in defending the legitimacy of new religious movements. Crucially, the religious activities of cults in the U.S. are protected under the First Amendment of the Constitution, which safeguards freedom of religion, speech, press, and assembly. However, this protection does not grant immunity from criminal prosecution for any members of religious groups or cults, reflecting a balance between religious liberty and legal accountability.

14. **Western Europe’s Stance: Brainwashing Theories and Judicial Scrutiny**

The landscape of governmental response in Western Europe presents a complex array of stances on cults, influenced by historical events and varying national legal traditions. Some governments, notably those of France and Belgium, have taken policy positions that have, at times, uncritically accepted ‘brainwashing’ theories. This acceptance has often led to more interventionist policies and the creation of official lists of groups deemed ‘cults’ or ‘sects,’ drawing significant concern from religious freedom advocates.

In contrast, other European nations, such as Sweden and Italy, have adopted a more cautious approach regarding brainwashing theories. As a result, their responses to new religions have been more neutral, reflecting a greater emphasis on empirical evidence and less on theories of undue influence. This divergence highlights a fundamental difference in how various European states balance governmental oversight with respect for religious pluralism and individual liberties.

Scholars have frequently suggested that the profound outrage and public outcry that followed high-profile tragedies, such as the mass murder-suicides perpetuated by the Solar Temple in the 1990s, significantly contributed to the strengthening of European anti-cult positions. These traumatic events often solidified public and political opinion, pushing governments towards more restrictive policies. Interestingly, the debate also saw clergymen and officials in countries like France express concern in the 1980s that some established orders and groups within the Roman Catholic Church itself could be adversely affected by proposed anti-cult laws, underscoring the broad and sometimes unforeseen implications of such legislative efforts.

As we conclude this comprehensive exploration, it becomes clear that the concept of ‘cult’ is far from static. It is a dynamic social construct, continuously shaped by evolving academic understanding, public perception, and governmental policy. Like a meticulously maintained classic automobile, the enduring ‘models’ of these social groups, be they theoretical frameworks, identifiable characteristics, or historical archetypes, offer timeless lessons in human behavior and societal interaction. By dissecting these phenomena with the rigor of an expert mechanic, we not only gain a deeper appreciation for their complexities but also equip future generations with the critical tools to navigate the multifaceted world of belief, influence, and devotion. These are indeed the classics worth handing down, not as objects of fear, but as profound lessons in the human condition, ensuring that we continue to learn from the intricate mechanics of our social world.