The concept of disease is a cornerstone of human experience, an ever-present force shaping individual lives and societies throughout history. From the fleeting discomfort of a common cold to the profound impact of chronic conditions, diseases touch every facet of our existence, influencing physical well-being, mental states, and even our social interactions. Understanding what constitutes a ‘disease’ – and how it differs from related terms like ‘illness’ or ‘disorder’ – is crucial for navigating the intricate landscape of health and pathology.

Indeed, the medical field continually refines its understanding and classification of these conditions, moving beyond simplistic interpretations to embrace the complex interplay of biological, environmental, and social factors. This ongoing evolution in our knowledge is not merely academic; it directly impacts diagnosis, treatment, and public health strategies, informing how we perceive and respond to health challenges at every level. It is a journey into the very fabric of what it means to be alive and vulnerable.

In this comprehensive exploration, we embark on a detailed journey through the multifaceted world of disease. We will unravel the precise definitions, distinguish between commonly interchanged terms, and systematically categorize the various forms diseases can take. Our aim is to provide a clear, authoritative, and in-depth perspective, drawing directly from established medical understanding to illuminate the fundamental nature of what adversely affects an organism.

At its core, a disease is precisely defined as a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism. Crucially, this condition is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often identified as medical conditions associated with specific signs and symptoms, providing clear indicators of their presence and impact on the body.

Such conditions can arise from a multitude of origins. They may be caused by external factors, prominently including pathogens, or they can stem from internal dysfunctions within the organism. For instance, internal dysfunctions of the immune system are known to produce a variety of different diseases, encompassing various forms of immunodeficiency, hypersensitivity, allergies, and autoimmune disorders.

In a broader human context, the term ‘disease’ is frequently employed to refer to any condition that causes pain, dysfunction, distress, social problems, or even death to the affected person. This expanded sense sometimes includes injuries, disabilities, disorders, syndromes, infections, isolated symptoms, deviant behaviors, and atypical variations of structure and function. Beyond the physical, diseases can profoundly affect individuals mentally, as contracting and living with a disease can significantly alter an affected person’s perspective on life.

While terms such as disease, disorder, morbidity, sickness, and illness are often used interchangeably in everyday language, there are specific contexts where distinct meanings are preferred, reflecting nuanced aspects of health and patient experience. The term ‘disease’ itself, as previously discussed, broadly refers to any condition that impairs the normal functioning of the body, intrinsically linked to the dysfunction of the body’s normal homeostatic processes. Clinically evident diseases resulting from pathogenic microbial agents—like viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and prions—are specifically referred to as infectious diseases, whereas conditions not producing clinically evident impairment, even if an infection is present, are not considered diseases.

‘Illness’ and ‘sickness’ are generally used as synonyms for disease, but ‘illness’ sometimes refers specifically to the patient’s personal experience of their condition. This means a person can have a disease without feeling ill—possessing an objectively definable yet asymptomatic medical condition, or a physical impairment without distress. Conversely, one can be ill without having a disease, such as when a normal experience is medicalized or perceived as a medical condition. Symptoms of illness often represent evolved responses, known as ‘sickness behavior,’ aimed at clearing infection and promoting recovery, encompassing effects like lethargy, depression, and loss of appetite.

‘Disorder’ denotes a functional abnormality or disturbance that may or may not present specific signs and symptoms. This term is often perceived as more value-neutral and less stigmatizing than ‘disease’ or ‘illness,’ making it preferred in certain circumstances, particularly in mental health. Medical disorders are broadly categorized into mental, physical, genetic, emotional, behavioral, and functional disorders, acknowledging the complex interplay of biological, social, and psychological factors.

Finally, a ‘medical condition’ or ‘health condition’ is a very broad concept encompassing all diseases, lesions, disorders, or even nonpathologic conditions that typically receive medical treatment, such as pregnancy. While it generally includes mental illnesses, in some contexts, it specifically denotes any illness, injury, or disease *except* for mental illnesses. This term is also sometimes chosen for its value-neutrality by those who do not consider their health issues deleterious, though it can also be rejected for its emphasis on the medical nature, as seen with proponents of the autism rights movement.

When we classify diseases, a fundamental framework involves dividing them into four main categories: infectious diseases, deficiency diseases, hereditary diseases, and physiological diseases. This classification provides a foundational understanding of the primary mechanisms through which conditions adversely affect organisms, guiding both research and medical practice. Each type represents a distinct pathway to impaired health, offering insights into the diverse threats to well-being.

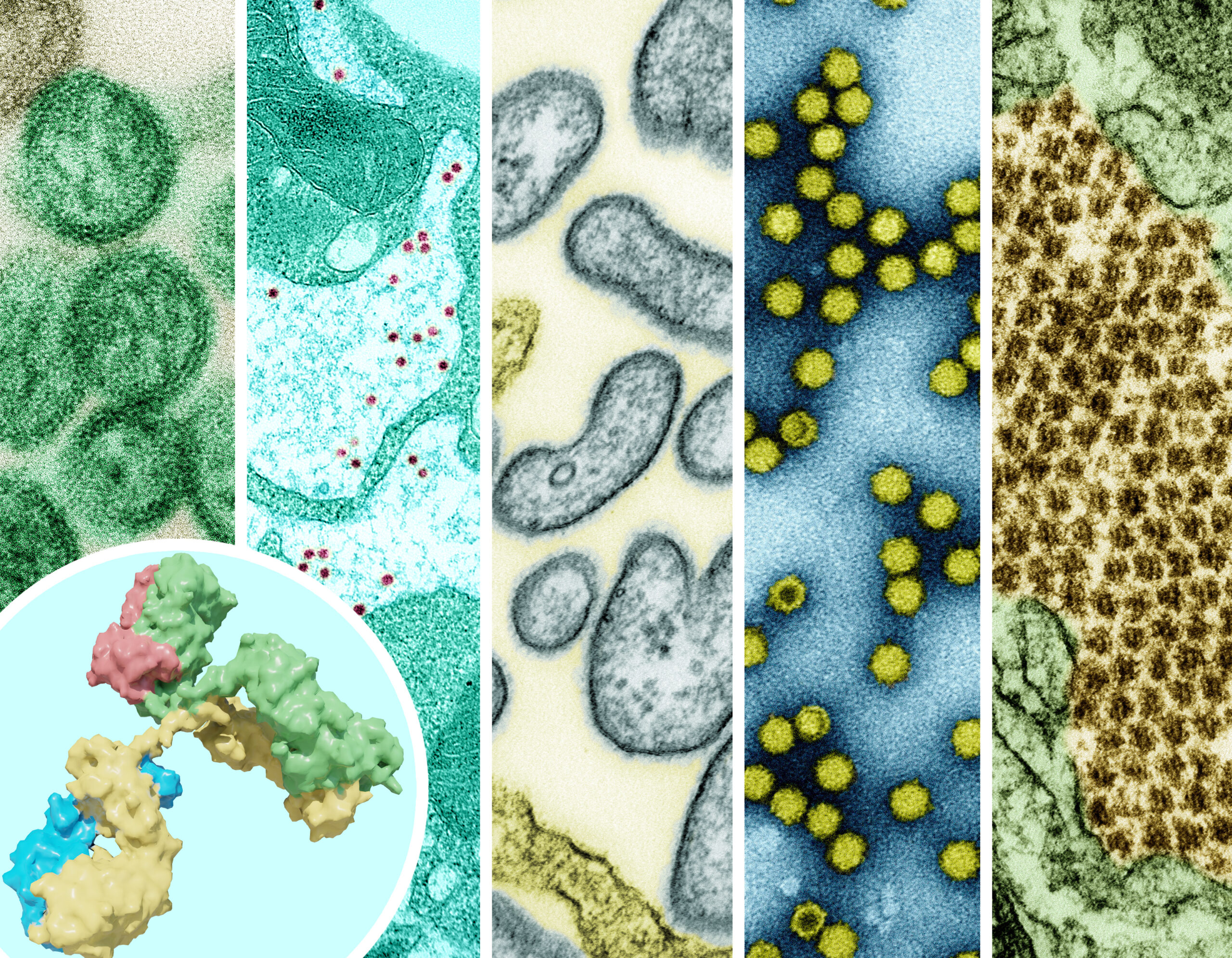

Infectious diseases, also known as transmissible or communicable diseases, are clinically evident illnesses resulting from the infection, presence, and growth of pathogenic biological agents within a host organism. These agents include viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, multicellular organisms, and even aberrant proteins known as prions. Their defining characteristic is the ability to spread, sometimes readily from person to person as with influenza, or through other means like contaminated food or water, or insect bites.

Deficiency diseases arise from a lack of essential nutrients or other crucial elements the body needs to function correctly. While the context does not elaborate on specific examples, this category highlights how the absence of necessary components, rather than the presence of an invading pathogen, can lead to severe health impairments. These conditions underscore the vital role of proper nutrition and environmental factors in maintaining health.

Hereditary diseases, a type of genetic disease, are caused by genetic mutations that are hereditary, meaning they can run in families and be passed down through generations. These conditions underscore the role of an individual’s genetic blueprint in predisposing them to certain health issues. It’s important to note that while many genetic diseases are inherited, some mutations can be random and de novo, meaning they appear for the first time in an individual.

Physiological diseases, sometimes referred to as organic diseases, are those caused by a physical or physiological change to some tissue or organ of the body. This term is commonly used in contrast with mental disorders and encompasses emotional and behavioral disorders if they are rooted in changes to the physical structures or functioning of the body, such as those occurring after a stroke or traumatic brain injury. This category highlights the impact of structural and functional integrity on overall health.

Read more about: The United States: A Complex Legacy of Discord and Unity, Shaping a Nation’s Evolving Identity

Diseases can also be classified based on their origin relative to an individual’s lifespan, providing a temporal perspective on when a condition first manifests. This distinction is critical for understanding the typical onset, potential causes, and appropriate medical approaches, separating conditions present from birth from those developed later in life. It helps define the natural history of a patient’s health challenges.

An acquired disease is one that began at some point during one’s lifetime, specifically after birth. The term simply means the condition was gained or developed over time, not that it was necessarily ‘caught via contagion.’ It is a broad category encompassing a vast array of conditions that arise due to environmental exposures, lifestyle choices, or other factors encountered post-natally. This contrasts sharply with conditions that are innate.

Conversely, a congenital disorder or congenital disease is explicitly defined as one that is present at birth. These conditions can often be genetic diseases or disorders, and many are inherited, carrying implications for family medical history. They can also be the result of a vertically transmitted infection, meaning an infection passed from the mother to the child during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding, such as HIV/AIDS.

Hereditary diseases, while often falling under the umbrella of congenital conditions, specifically refer to a type of genetic disease caused by genetic mutations that are hereditary. This means these mutations are capable of being passed down from parents to their offspring, thereby having the potential to run in families. The distinction emphasizes the transgenerational nature of these specific genetic conditions, highlighting the importance of family history in diagnosis and risk assessment.

Understanding the duration and typical progression of a disease is fundamental to its characterization and management. Medical professionals categorize conditions based on their temporal nature, offering insights into the expected course of illness, the urgency of treatment, and the long-term impact on a patient’s life. This temporal classification aids in setting appropriate expectations for recovery and ongoing care.

An acute disease is characterized by its short-term nature, often appearing suddenly and resolving relatively quickly. The common cold serves as a prime example of an acute disease, demonstrating a rapid onset of symptoms followed by a relatively swift recovery. The term ‘acute’ can also connote a fulminant nature, implying a severe and rapid onset of symptoms or progression.

In stark contrast, a chronic disease is one that persists over an extended period, typically defined as lasting for at least six months, but often continuing for the entirety of one’s natural life. These conditions may be constantly present, or they might go into remission, only to periodically relapse. Chronic diseases can be stable, meaning they do not worsen over time, or they can be progressive, indicating a worsening trajectory. While many chronic diseases cannot be permanently cured, most can be beneficially treated to manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

Progressive disease describes a condition whose typical natural course involves the worsening of the disease over time, often leading to death, serious debility, or organ failure. Slowly progressive diseases are a subset of chronic diseases, and many also fall into the category of degenerative diseases, characterized by a gradual decline in function. The opposite of a progressive disease is a stable disease or static disease, which exists but does not improve or worsen, maintaining a consistent state over time.

Delving into the causes of disease reveals categories that highlight specific challenges in medical understanding and intervention. Some conditions present a puzzle where the origin remains elusive, while others are unintended consequences of medical care itself. These classifications underscore the complexities inherent in diagnostic processes and the delicate balance of therapeutic interventions.

An idiopathic disease is defined as one that has an unknown cause or source. Historically, many diseases were considered idiopathic before advancements in medical science shed light on their origins. As knowledge progresses, some diseases with entirely unknown causes have had aspects of their sources explained, thus shedding their idiopathic status. For example, the discovery of germs elucidated their role in infections, even before specific links between germs and diseases were fully understood. While certain factors may be associated with these diseases, association does not inherently imply causality; a third, unknown factor might be responsible for both the disease and the associated phenomenon.

In stark contrast, an iatrogenic disease or condition is one that is caused directly by medical intervention. This can occur either as a known side effect of a treatment or as an inadvertent, unintended outcome of a medical procedure or therapy. These conditions are a reminder of the inherent risks in medical care, emphasizing the importance of careful clinical decision-making, patient monitoring, and continuous improvement in medical practices to minimize harm.

Understanding the relationship between different health conditions often involves distinguishing between primary and secondary diseases. This distinction is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment, as identifying the root cause allows for targeted interventions rather than merely addressing symptoms. It helps clinicians unravel complex medical presentations.

A primary disease is recognized as the underlying or root cause of an illness. It is the initial condition that sets off a chain of events leading to further health problems. For instance, a common cold is typically considered a primary disease. Its presence can then lead to subsequent conditions or complications. Identifying the primary disease is paramount for devising a comprehensive treatment strategy that addresses the fundamental issue rather than just its manifestations.

In turn, a secondary disease is defined as a sequela or complication that arises from a prior, causal disease, which is referred to as the primary disease or simply the underlying cause. For example, if a common cold (the primary disease) leads to rhinitis (inflammation of the nasal passages), the rhinitis would be considered a possible secondary disease or sequela. Similarly, a bacterial infection can be primary when a healthy person is exposed and becomes infected, or it can be secondary to another primary cause that predisposes the body to infection.

Consider a scenario where a primary viral infection weakens the immune system; this weakened state could then lead to a secondary bacterial infection. Another example is a primary burn that creates an open wound, providing an entry point for bacteria and consequently leading to a secondary bacterial infection. In clinical practice, a doctor must meticulously determine what primary disease, such as a cold or a more severe bacterial infection, is truly causing a patient’s secondary symptoms like rhinitis, as this determination directly impacts the decision on whether to prescribe antibiotics and what course of treatment is most appropriate.

The journey into understanding disease would be incomplete without a thorough examination of its manifold origins, which vary significantly in their nature and impact. Diseases can stem from an array of factors, broadly categorized as acquired, meaning they develop during an individual’s lifetime, or congenital, signifying their presence at birth. Microorganisms, genetics, and environmental factors frequently contribute, either singly or in combination, to the onset of a diseased state, underscoring the intricate web of influences on health.

While some diseases, like influenza, are commonly known to be contagious and infectious, caused by microorganisms termed pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and fungi, not all diseases fit this profile. Infectious diseases can be transmitted through diverse routes, including hand-to-mouth contact with contaminated surfaces, insect bites, or via polluted water and food, often linked to fecal contamination. Sexually transmitted diseases represent another significant category within this domain.

Crucially, many prevalent conditions, including most forms of cancer, heart disease, and mental disorders, are classified as non-infectious. These conditions cannot be spread directly from one person to another and often possess a partial or complete genetic basis, making them potentially transmissible across generations. Beyond biological causes, the ‘social determinants of health,’ recognized by bodies like the World Health Organization, highlight the profound influence of social, economic, political, and environmental circumstances on collective and personal well-being, particularly in contexts of poverty. When the cause of a disease remains poorly understood, societies have historically tended to mythologize it or use it as a metaphor for perceived social ills, as seen with tuberculosis before its bacterial origin was identified. It is also vital to distinguish the pathogen, the causal agent (e.g., Plasmodium), from the disease itself (e.g., malaria).

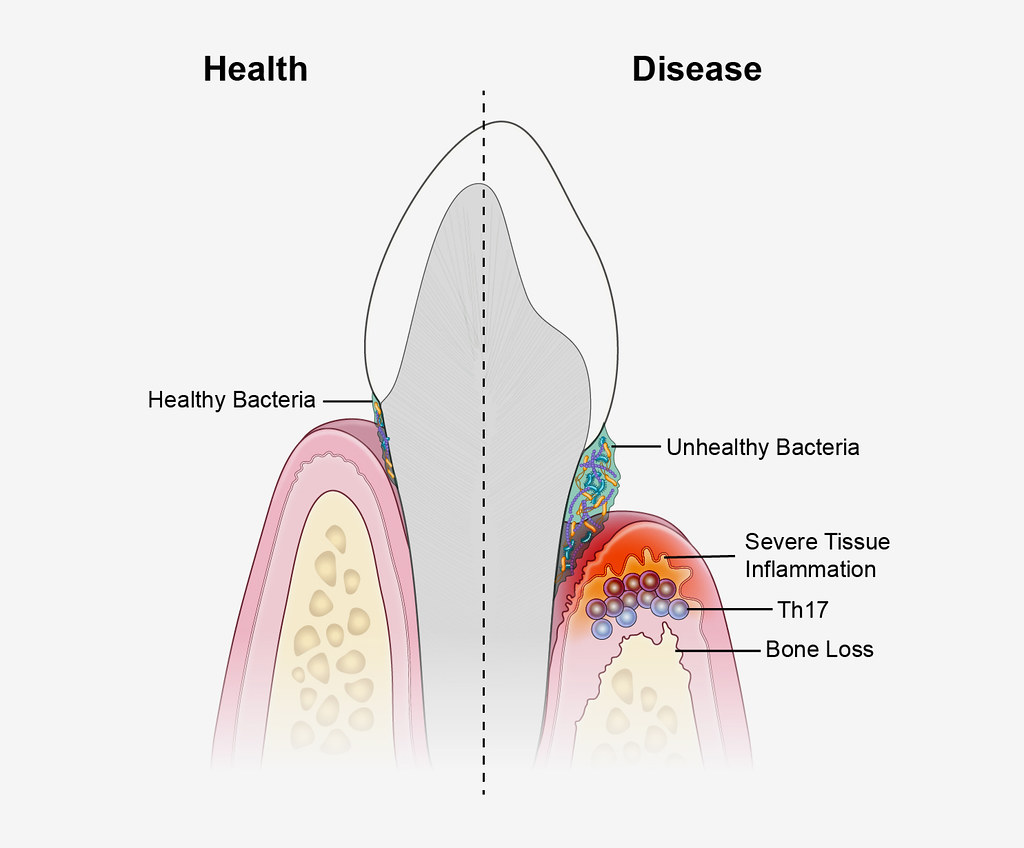

Understanding how diseases manifest and spread within an individual’s body is crucial for effective diagnosis and treatment, necessitating a classification based on their extent. A disease can be confined to a specific area, affecting only one part of the body, or it can spread more broadly, impacting multiple systems. This categorization helps medical professionals localize the problem and determine the scope of necessary intervention.

A localized disease is precisely what its name implies: a condition that affects only a single part of the body. Examples such as athlete’s foot, which impacts only the feet, or an eye infection, confined to the ocular region, illustrate this category. These conditions, while potentially uncomfortable, are limited in their immediate anatomical reach, allowing for targeted local treatments that do not necessarily involve the entire organism.

In contrast, a disseminated disease signifies a condition that has spread beyond its initial site to other parts of the body. In the context of cancer, this spread is more commonly known as metastatic disease, a critical indicator of advanced progression. Further along this spectrum is a systemic disease, which affects the entire body. Influenza, for instance, impacts multiple bodily systems, causing widespread symptoms like fever, body aches, and fatigue, rather than being confined to a single organ. Similarly, high blood pressure is a systemic condition that influences the cardiovascular system throughout the body, demonstrating its pervasive impact on an individual’s overall health.

The proactive approach to health, emphasizing the avoidance of illness and injury before they even begin, stands as a cornerstone of public health and individual well-being. Preventive medicine encompasses a wide array of measures designed to maintain health and deter the onset of disease, thereby reducing the burden on healthcare systems and improving quality of life. These strategies range from personal habits to large-scale public health initiatives.

Key among these preventative measures are robust sanitation practices, which play a critical role in controlling the spread of infectious agents by ensuring clean environments and safe water supplies. Proper nutrition, providing the body with essential vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients, is fundamental for bolstering the immune system and supporting overall physiological function, thereby preventing deficiency diseases and strengthening resistance to various ailments. Adequate physical exercise also contributes significantly to disease prevention, particularly for lifestyle-related conditions, by maintaining cardiovascular health, managing weight, and improving metabolic function.

Furthermore, vaccinations represent a highly effective public health intervention, offering targeted protection against specific infectious diseases by stimulating the body’s immune response without causing illness. Beyond these broad categories, self-care practices—including good hygiene, sufficient rest, and stress management—empower individuals to take active roles in their own health maintenance. Public health measures, such as obligatory face mask mandates during epidemics, exemplify collective efforts to mitigate disease transmission and protect the broader community, demonstrating a multi-faceted approach to fortifying societal health against diverse threats.

Once a medical problem has manifested, the focus shifts from prevention to intervention, encompassing a range of efforts aimed at alleviating symptoms, improving the condition, or even achieving a complete resolution. Medical therapies, often synonymous with ‘treatment,’ represent the concerted actions taken to address a disease or other health issues, aiming to restore functionality and quality of life. These interventions are diverse, spanning from pharmacological solutions to complex surgical procedures.

Common treatments employed in modern medicine include medications, which can manage symptoms, halt disease progression, or directly target pathogens. Surgical interventions address structural abnormalities or remove diseased tissues, while medical devices provide support or replace impaired functions. Beyond these clinical applications, self-care remains a vital component of treatment, empowering patients and their families to manage their conditions daily, often in conjunction with professional medical guidance. Psychotherapy, frequently referred to as ‘talk therapy’ by psychologists, is another significant form of treatment, particularly for mental health conditions, focusing on cognitive and emotional well-being.

It is crucial to differentiate between treatment and cure. While a treatment endeavors to improve or remove a problem, it does not always lead to a permanent cure, especially in the context of chronic diseases where ongoing management is often necessary. A ‘cure,’ a subset of treatments, signifies the complete reversal of a disease or the permanent resolution of a medical problem. Many diseases, even if incurable, can be effectively managed through beneficial treatments, enhancing the patient’s quality of life. Pain management, a specialized branch of medicine, employs an interdisciplinary approach to relieve pain and improve the daily lives of those afflicted by chronic discomfort. In acute or life-threatening situations, medical emergencies necessitate prompt intervention, often facilitated through specialized emergency departments or urgent care facilities to ensure timely and critical care.

Epidemiology stands as a foundational scientific discipline within public health, dedicated to the study of factors that drive or influence diseases within populations. It delves into why certain diseases are more prevalent in specific geographical regions, among particular genetic or socioeconomic groups, or during various times of the year, providing critical insights into disease distribution and determinants. This rigorous analytical approach is essential for understanding the dynamics of health and illness across communities.

Considered a cornerstone methodology in public health research, epidemiology is highly valued in evidence-based medicine for its capacity to identify risk factors for diseases. Epidemiologists undertake diverse tasks, ranging from urgent outbreak investigations to meticulous study design, comprehensive data collection, and sophisticated analysis, which includes developing statistical models to test hypotheses and meticulously documenting findings for peer-reviewed publication. Their work also extends to studying the complex interplay of multiple diseases within a population, a phenomenon known as a syndemic.

To accomplish their objectives, epidemiologists draw upon a multitude of other scientific disciplines. Biology informs their understanding of disease processes, while biostatistics provides the necessary tools for analyzing raw information. Geographic Information Science (GIS) is utilized for storing data and mapping disease patterns, offering a visual representation of health trends. Furthermore, social science disciplines contribute by enhancing comprehension of both proximate and distal risk factors, recognizing the broader societal influences on health. By integrating these varied fields, epidemiology effectively helps to identify disease causes and guides the development of targeted prevention efforts, ultimately contributing to a more effective public health response.

To fully grasp the societal impact of health problems, beyond individual suffering, various measures are employed to quantify the burden imposed by diseases on populations. This ‘disease burden’ is assessed through indicators such as financial cost, mortality rates, morbidity, and other metrics that provide a comprehensive view of the health challenges faced by a community or globally. Such quantification is vital for resource allocation and public health policy.

One straightforward measure is the ‘years of potential life lost’ (YPLL), which estimates the number of years an individual’s life was shortened due to a disease. For instance, if a person dies at 65 from a disease but would have likely lived to 80, the disease accounts for 15 YPLL. However, YPLL does not account for the quality of life or disability prior to death, treating a sudden death and a prolonged illness leading to death at the same age as equivalent. In 2004, the World Health Organization reported a staggering 932 million YPLL due to premature death, highlighting the global scale of early mortality from disease.

More nuanced metrics, such as the ‘quality-adjusted life year’ (QALY) and ‘disability-adjusted life year’ (DALY), integrate not only years lost to premature death but also years lived with disability or illness. These measures account for how healthy a person was after diagnosis, revealing the burden on individuals who, despite living a normal lifespan, endure significant illness. A disease with high morbidity but low mortality, for example, would have a high DALY but a low YPLL. In 2004, the WHO estimated 1.5 billion DALYs were lost to disease and injury worldwide, indicating the immense global impact of illness and disability. In developed nations, while cardiovascular diseases lead to the most life loss, neuropsychiatric conditions like major depressive disorder are responsible for the highest number of years lost to being sick, underscoring the pervasive and often underestimated burden of mental health conditions.

The way a society perceives, interprets, and responds to disease extends far beyond its biological manifestations, becoming a significant subject within medical sociology. Cultural beliefs, historical contexts, and societal values profoundly shape how conditions are defined, understood, and experienced, often influencing whether a state is even considered a ‘disease’ at all. This dynamic interplay highlights the fluid nature of medical classification and its broader implications.

Certain conditions may be recognized as diseases in some cultures or historical periods but not in others. For example, obesity was once a symbol of prosperity and abundance in Renaissance culture, a perception that regrettably persists in parts of Africa, particularly in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic where body mass can signify health. Conversely, among the Hmong people, epilepsy is sometimes seen not as an ailment but as a sign of spiritual gifts, illustrating a distinct cultural lens through which health is interpreted. The identification of a condition as a disease, rather than a mere variation, carries substantial social and economic weight, influencing governmental responsibilities, corporate policies, and individual lives, as evidenced by the controversial recognition of conditions like repetitive stress injury (RSI) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Furthermore, sickness often confers a distinct social role, known as the ‘sick role,’ which comes with certain legitimizing benefits, such as illness benefits, exemption from work, and the right to be cared for by others. In return for these privileges, the sick person is typically obligated to seek treatment and strive for recovery. Religious practices frequently grant exceptions from duties to those who are ill, such as fasting exemptions. Social standing and economic status also significantly influence health outcomes, leading to the concept of ‘diseases of poverty’ versus ‘diseases of affluence.’ While poverty-related diseases are associated with low social status, affluence-related diseases are linked to higher social standing and often longer lifespans, such as various cancers becoming more common in societies where people live longer. The language used to describe disease, often employing military metaphors (‘fighting a battle’) or journey narratives (‘road to recovery’), further embeds these biological phenomena within cultural frameworks, shaping both individual experience and collective response.

As we conclude this comprehensive exploration into the nature of disease, it becomes profoundly clear that these conditions are far more than mere biological aberrations. They are intricate phenomena shaped by a confluence of biological, environmental, social, and cultural forces, continuously evolving in our understanding and challenging humanity to adapt. From the precise definitions of pathology to the nuanced impacts quantified by epidemiology, and from the strategies of prevention to the complexities of treatment, our collective knowledge empowers us to confront these challenges with greater precision and compassion. By recognizing the multifaceted dimensions of disease, we not only advance medical science but also foster a more empathetic and resilient society, better equipped to promote well-being for all.