For many of us, navigating daily nutrition can feel like a straightforward task, but for neurodivergent individuals, the journey through food and eating habits is often uniquely challenging. Conditions like ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and other neurological or developmental variations mean that brains function differently, influencing how individuals perceive the world—and their meals. These differences aren’t about ‘doing things wrong’; they’re about diverse wiring that requires a tailored, empathetic approach to support overall health and happiness.

From intense sensory sensitivities that make certain textures unbearable to difficulties recognizing the simple cues of hunger and fullness, the complexities are vast. Heightened anxiety around food choices, digestive discomfort that mimics intolerances, and even the intense focus of hyperfixation can all contribute to a relationship with food that feels confusing or frustrating. But by understanding these specific impacts, we can begin to build sustainable, nourishing eating patterns that truly work with the neurodivergent brain, not against it.

This guide is designed to empower you with actionable insights and practical advice, drawing on expert knowledge to help navigate these challenges. We’ll explore the various ways neurodivergence influences eating and offer strategies to foster a more positive, confident, and relaxed approach to food, ensuring that physical and mental well-being are supported every step of the way. It’s about finding a rhythm that works for you or your loved one, celebrating individual preferences, and embracing flexibility.

1. Unpacking the Unique Nutritional Landscape of Neurodivergence

Neurodivergence, encompassing conditions such as Autism Spectrum Condition, ADHD, dyslexia, and dyscalculia, describes the natural diversity in human brain function. These variations mean individuals perceive the world in their own unique ways, which profoundly impacts their thoughts, behaviors, and crucially, their eating habits. Many neurodivergent clients arrive feeling frustrated with their eating habits, often unaware that their neurodivergence, diagnosed or not, plays a significant role in these struggles.

Sensory sensitivities are a hallmark of many neurodivergent experiences, transforming everyday meals into a potential sensory assault. A neurodivergent individual may find specific textures, tastes, smells, or even the appearance of food overwhelming or intensely disgusting, far beyond simple pickiness. This can lead to a severely limited diet, which, if not managed carefully, can result in nutritional gaps and associated health consequences.

Beyond sensory input, challenges extend to internal bodily cues and emotional regulation. Difficulties recognizing hunger and fullness, heightened anxiety about food choices, and even digestive discomfort that can be mistakenly attributed to specific foods are common patterns. These are not failures of willpower, but rather a reflection of how a neurodivergent brain processes sensory input, emotions, and interoceptive signals—the body’s ability to perceive internal sensations. Recognizing these patterns is often a crucial ‘aha’ moment, paving the way for more effective support.

Ultimately, understanding this unique nutritional landscape means shifting our perspective. It requires acknowledging that neurodivergent individuals are not broken and do not need mending; they are simply wired differently. The goal is to install coping mechanisms and build an environment that supports their unique needs, rather than trying to force them into a neurotypical framework. This foundational understanding is the first step towards a more compassionate and effective approach to nutrition.

2. Navigating the Rhythms of Irregular Eating: Hyperfocus and Emotional Responses

One common pattern observed among neurodivergent individuals is the presence of irregular eating habits. This often manifests in two primary ways: forgetting to eat due to intense hyperfocus, or conversely, eating excessively in response to emotional overwhelm. These aren’t intentional choices but rather outcomes of how a neurodivergent brain processes and reacts to its environment and internal states, particularly for those with ADHD or autism.

Hyperfocus, a characteristic often seen in ADHD, can lead an individual to become so deeply engrossed in a task or interest that they lose track of time and basic bodily needs, including hunger. Hours can pass without a meal, leading to sudden, intense hunger, irritability, or exhaustion. This unpredictable eating pattern can contribute to significant blood sugar fluctuations, making it even harder to manage mood, energy, and focus throughout the day. The brain, reliant on a steady supply of energy, struggles when fuel intake is inconsistent.

On the other end of the spectrum, emotional overwhelm can trigger excessive eating. For neurodivergent individuals who may experience heightened anxiety or difficulty regulating emotions, food can become a source of comfort or a coping mechanism. This isn’t about hunger but about seeking relief from intense feelings, which can lead to discomfort, guilt, or further distress. Understanding this link between emotions and eating patterns is essential for developing healthier coping strategies.

A practical strategy to manage these irregular patterns is to introduce a gentle structure around meals. This doesn’t mean rigid rules, but rather a general framework or routine that helps ensure consistent nourishment. Incorporating protein- and fat-rich foods at each meal is particularly beneficial, as these macronutrients support stable energy levels, mood, and focus. By finding a rhythm that accommodates the brain’s unique processing, the entire experience of eating and daily functioning can feel significantly easier and more predictable.

3. Taming Extreme Sensory Responses and Food Aversions

For many neurodivergent individuals, food is not just about taste; it’s a multi-sensory experience that can be overwhelming. Extreme sensory responses—strong aversions to certain textures, tastes, temperatures, smells, and even the appearance of foods—are a major reason why diets can become incredibly limited. This is far beyond typical fussiness; it’s an intense disgust and often a genuine fear at the prospect of eating certain items. These responses are particularly common in people on the autistic spectrum, where hypersensitivity can make sensory input feel uncomfortable or even painful.

Take, for instance, common protein-rich foods like fish, eggs, or certain meats. Their specific textures, smells, or temperatures can feel unbearable to someone with heightened sensory sensitivities. Similarly, fibrous vegetables with strong tastes or unique mouthfeels can be immediate no-gos. In a world that can already be demanding and anxiety-inducing for neurodivergent individuals, avoiding foods that contribute to sensory overload becomes a necessary coping mechanism, even if it restricts nutritional intake.

These intense aversions can sometimes escalate into Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), an eating disorder characterized by sensory aversion to foods, fear of negative consequences like choking or vomiting, fear of new foods, and a general lack of interest in eating. ARFID often goes hand-in-hand with neurodivergence, highlighting the profound link between sensory processing and dietary habits. For example, issues with oral motor skills, like chewing, common in autistic individuals, can lead to avoiding foods that are perceived as choking hazards.

Instead of attempting to force the consumption of foods that trigger such intense negative reactions, the focus should be on respectful experimentation and finding tolerable alternatives. The goal is not about achieving a ‘perfect’ diet immediately, but about broadening the nutritional spectrum in ways that honor sensory needs. This compassionate approach acknowledges that discomfort isn’t a choice and that working with, rather than against, sensory profiles is key to sustainable dietary improvement.

4. Calming Food-Related Anxiety: From Rigid Rules to Mindful Choices

Heightened anxiety is a significant factor in the lives of many neurodivergent individuals, and it frequently spills over into their relationship with food. This can manifest as an intense worry about eating the ‘right’ way, leading to the development of very rigid food rules. These rules are often self-imposed and can create an immense amount of stress around meal times, turning what should be a nourishing experience into a source of constant apprehension and guilt after eating.

Another common manifestation of this anxiety is hyper-awareness of digestive symptoms. Neurodivergent individuals may become acutely attuned to sensations like bloating or discomfort, often jumping to the conclusion that a specific food must be the culprit. This can lead to the unnecessary elimination of foods, further restricting an already limited diet based on assumption rather than confirmed intolerance. While true food intolerances exist, it’s crucial to recognize that stress itself has a profound impact on digestion.

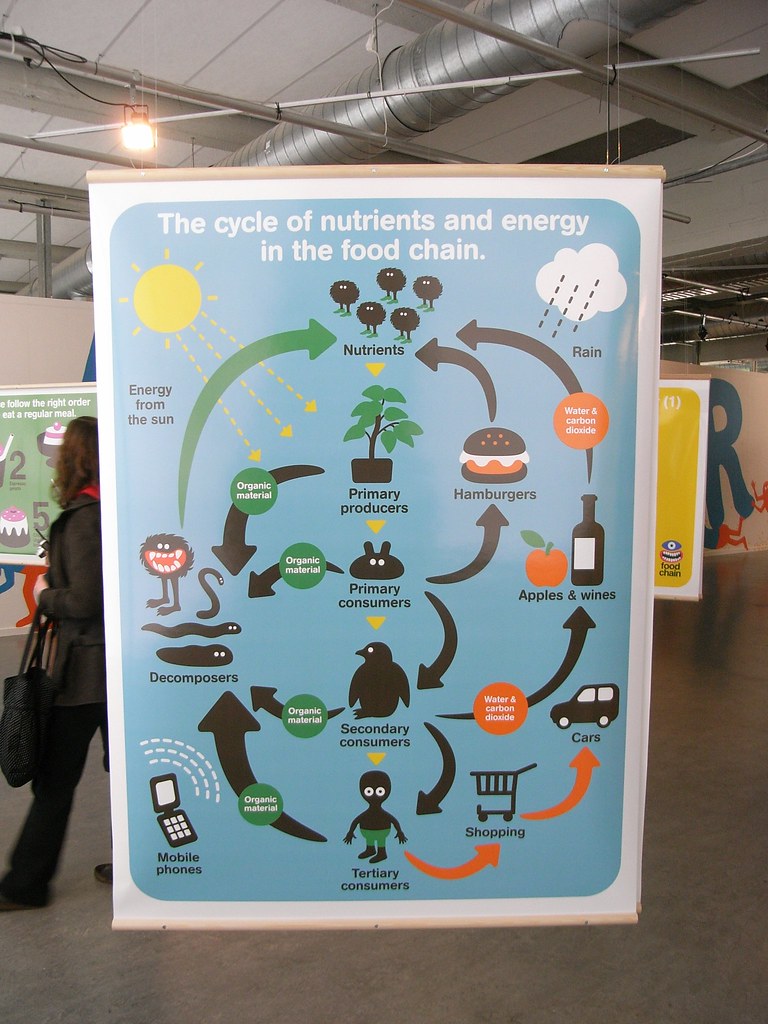

The gut and brain are intimately linked through the gut-brain axis, meaning that anxiety, stress, and overthinking about food choices can directly trigger or exacerbate gut symptoms. This creates a vicious cycle: anxiety about food leads to digestive discomfort, which then reinforces the belief that certain foods are ‘bad,’ increasing anxiety even further. Breaking this cycle requires a shift from an immediate focus on restriction to a broader approach that supports overall digestive well-being and mental calm.

Rather than automatically eliminating foods, strategies that support digestion in other ways can be incredibly beneficial. Incorporating gut-supportive foods such as fiber-rich vegetables, fermented foods, and omega-3s can aid digestive health. Equally important are relaxation techniques practiced around meals, like deep breathing and mindful eating. These practices help calm the nervous system, which in turn can reduce stress-induced gut symptoms. The emphasis moves from fear-driven restriction to proactive, compassionate nourishment, making food feel less overwhelming and more manageable.

5. Understanding and Easing Digestive Discomfort: The Gut-Brain Connection

Digestive discomfort, including symptoms like bloating, irregular bowel movements, or general abdominal unease, is a common challenge for neurodivergent individuals. Often, these sensations are mistakenly attributed to specific foods, leading to avoidance behaviors that can further narrow an already restricted diet. However, emerging research and clinical experience highl ight a crucial underlying factor: the powerful bidirectional communication between the gut and the brain, known as the gut-brain connection.

This intricate link means that the gut is often referred to as the ‘second brain,’ directly influencing mood, cognitive function, and even behavioral patterns. For neurodivergent individuals, unique gut microbiota profiles—the community of microorganisms living in the digestive system—can impact their cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning. This connection also implies that psychological stress, including the heightened anxiety frequently experienced by neurodivergent individuals, can significantly impact gut health, sometimes triggering digestive symptoms independently of specific food intolerances.

Recognizing that stress and anxiety can directly trigger gut symptoms is a pivotal insight. Instead of immediately restricting foods based on perceived negative effects, a more holistic approach focuses on supporting digestion through various avenues. This includes incorporating gut-supportive foods such as fiber-rich vegetables, which aid healthy bowel function and feed beneficial gut bacteria, and fermented foods, which provide beneficial probiotics that contribute to a balanced gut microbiome. Omega-3s are also crucial for reducing inflammation throughout the body, including the gut.

Furthermore, practices that calm the nervous system around meal times can make a substantial difference. Deep breathing exercises before eating or practicing mindful eating, where attention is fully placed on the meal experience, can reduce the anxiety that exacerbates gut symptoms. Identifying true food triggers through careful observation, rather than assumption, is also key. By understanding and addressing the gut-brain connection, we can foster a healthier digestive system and a more relaxed relationship with food, moving towards nourishment over fear.

6. Decoding Your Body’s Signals: Mastering Hunger and Fullness Cues

One of the most significant challenges neurodivergent individuals, particularly those with ADHD or autism, face is difficulty recognizing hunger and fullness cues. This struggle often stems from differences in interoception, which is the body’s ability to perceive internal signals like a growling stomach or a feeling of satiety. As a result, it’s easy to miss subtle signs of hunger until they escalate to an intense, sudden ravenousness, often accompanied by irritability or extreme exhaustion.

Conversely, some neurodivergent individuals may struggle equally to recognize when they are comfortably full. This can lead to overeating, physical discomfort, and sometimes feelings of guilt or distress after meals. The absence of clear internal signals makes it difficult to regulate food intake effectively, contributing to inconsistent eating patterns and potential digestive issues. These interoceptive differences mean that the body’s natural regulatory mechanisms aren’t always communicating clearly with the brain.

A highly practical and effective way to manage these challenges is to create structure around meals. This doesn’t imply strict, inflexible rules, but rather a general framework or a loose routine that helps ensure regular nourishment. Having scheduled meal and snack times, even if appetite isn’t strongly felt, can provide the body with consistent fuel. This predictability helps to stabilize blood sugar levels, which in turn supports more consistent energy, mood, and focus throughout the day, making daily tasks feel less arduous.

To further support stable energy and mood, incorporating protein- and fat-rich foods at each meal is often encouraged. Protein and healthy fats are digested more slowly, providing sustained energy release compared to carbohydrates alone, thereby preventing sharp blood sugar fluctuations that can make everything feel harder. By proactively building a rhythm and structure into eating, and focusing on nutrient-dense foods, neurodivergent individuals can significantly improve their ability to manage hunger and fullness, fostering a more balanced and comfortable eating experience.

7. Crafting a Sensory-Friendly Diet: Practical Strategies for Nutritional Gaps

Sensory sensitivities are a predominant reason why many neurodivergent individuals maintain a limited diet, often leading to nutritional gaps. The overwhelming nature of certain textures, flavors, and smells can make a wide variety of foods seem intolerable. This is not a matter of choice but a genuine physical and psychological response, making it difficult to consume essential nutrients from diverse food groups. Recognizing this is the first step towards creating a truly supportive and nourishing approach to eating.

Instead of trying to force the consumption of foods that trigger extreme discomfort, a more effective strategy involves experimenting with alternative options and modifying existing ones. For instance, if the texture of meat, fish, or eggs is a significant barrier, explore plant-based proteins like legumes, tofu, or lentils, or consider dairy products. Softer-cooked meats can also be more tolerable than chewier cuts. The key is finding protein sources that align with individual sensory preferences, ensuring adequate intake for brain function and overall health.

Vegetables, often a source of vital vitamins and fiber, can also present sensory challenges due to their bitterness, crunchiness, or fibrous textures. In these cases, blending vegetables into soups, sauces, or smoothies can be a game-changer. This alters the texture and sometimes masks intense flavors, making them more palatable. For example, spinach or kale can be easily incorporated into a fruit smoothie without significantly changing the primary sensory experience, yet providing crucial nutrients.

Temperature, texture, and seasoning can all be adjusted to make a significant difference in how tolerable a food feels. Some individuals prefer all foods cold, others warm, and some strictly room temperature. Experimenting with different cooking methods to achieve desired textures—crispy, soft, pureed—is also valuable. Modifying seasonings to reduce strong tastes or enhance preferred ones can open up new possibilities. The overarching goal is practicality: finding sustainable ways to meet nutritional needs while profoundly respecting individual sensory profiles, rather than striving for an unrealistic dietary perfection.

Building on our understanding of the unique challenges neurodivergent individuals face with food, the next crucial step is to build sustainable solutions. This involves a multi-faceted approach, focusing on essential nutrient support, flexible eating strategies that truly work, and empowering techniques for caregivers to foster a positive and nourishing relationship with food. It’s about creating an environment where nutrition supports well-being, rather than being a source of stress or frustration.

8. Boosting Brain Health with Targeted Nutrition: The Power of Key Nutrients

Supporting brain function through nutrition is one of the most impactful tools available for managing mood, focus, and energy in neurodivergent individuals. Instead of broad, generic dietary advice, a targeted approach that prioritizes specific nutrients can yield significant benefits. These nutrients act as the building blocks and regulators for various brain processes.

By making small, consistent shifts in their daily diet to incorporate more of these vital nutrients, individuals often experience noticeable improvements. This can translate to enhanced focus, a more stable mood, and overall improved well-being, making daily life feel less overwhelming. The brain, after all, relies on a steady supply of high-quality fuel to operate optimally.

The brain is constantly working, requiring a wide array of vitamins, minerals, and healthy fats to regulate mood, nourish the nervous system, and support essential functions like memory, focus, and learning. When a diet is restricted due to sensory or anxiety-related issues, it may not provide enough of these critical nutrients, potentially exacerbating neurodivergent behaviors. Identifying and addressing these gaps is fundamental for comprehensive support.

9. Protein and Healthy Fats: Fueling Focus and Mood Stability

Protein plays a pivotal role in supporting crucial brain chemistry, particularly in the production of neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin. These chemical messengers are essential for regulating mood, motivation, and cognitive function. Good sources to consider include lean meats, fish, eggs, dairy products, legumes, nuts, and seeds, offering a diverse range of options.

It’s important to clarify that neurodivergent individuals generally do not require *more* protein than neurotypical individuals. However, their diets are often restricted due to sensory sensitivities or food-related anxiety, making it challenging to meet basic protein requirements. The unique textures and smells of common protein-rich foods like meat, fish, or eggs can present significant barriers.

Alongside protein, healthy fats are indispensable for optimal cognitive function and for reducing neuroinflammation throughout the body. Omega-3 fatty acids, in particular, are vital for brain cell structure and communication. Excellent sources of healthy fats include fatty fish, flaxseeds, walnuts, and olive oil, all of which contribute to a well-nourished and resilient brain.

10. The Micronutrient Superstars: Magnesium, Zinc, Iron, and B Vitamins

Magnesium is a true powerhouse, known for its ability to help manage symptoms linked to stress and anxiety. It works by reducing the activity of excitatory neurotransmitters and supporting serotonin transmission, which are key for mood regulation. Furthermore, magnesium is crucial for smooth muscle function, with low levels often linked to muscle tension, cramps, and headaches. When considering supplementation, prioritizing a highly bioavailable chelated form is essential for optimal absorption.

Zinc is another critical mineral, required for healthy methylation, efficient brain cell communication, and the production of vital neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine. Its role in cognitive function and mood stability cannot be overstated. When selecting zinc supplements, the form matters; zinc picolinate, for instance, offers a higher rate of absorption compared to other types, ensuring the body can effectively utilize this nutrient.

Iron is indispensable for numerous brain functions, including oxygen transportation, energy production within brain cells, and normal methylation processes. It also plays a significant role in manufacturing mood-regulating chemicals like serotonin and dopamine. Many iron supplements are notorious for causing constipation, making it crucial to opt for a gentle, non-constipating form such as iron bisglycinate to avoid further digestive discomfort.

The B vitamins are a comprehensive group crucial for energy metabolism and overall nervous system health. Folate, along with other B-vitamins, directly supports the production of neurotransmitters that regulate mood, memory, and mental focus. Folate, B12, B6, magnesium, iron, and zinc are all essential for healthy methylation—a biological ‘switch’ activating billions of processes. Notably, some research indicates that people with autism may have significantly lower brain levels of B12 due to genetic differences, underscoring the importance of methylated, active forms when considering B12 or folate supplementation.

11. Omega-3s: Brain Cell Structure, Function, and Reducing Inflammation*

Omega-3 fatty acids, specifically DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) and EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid), are fundamental components for robust brain cell structure and function. They are also critical for managing inflammation throughout the body, including within the brain. These essential fats cannot be produced by the body and must be obtained through diet or supplementation, making their consistent intake vital for neurodivergent individuals.

A substantial body of research has explored the link between omega-3s and neurodiversity, particularly focusing on ADHD in children. The results are promising, especially in cases where baseline omega-3 levels are low. Studies have documented improvements in areas such as impulsiveness and hyperactivity, alongside positive effects on oxidative stress, inflammatory markers, and even the gut microbiome.

These findings highlight the powerful potential of omega-3 supplementation as a supportive strategy. By providing the brain with these essential fats, it’s possible to enhance its resilience and improve various aspects of cognitive and emotional regulation. This makes omega-3s a cornerstone of nutritional support for fostering overall well-being in neurodivergent individuals.

12. Embracing Food Chaining: A Gentle Path to Dietary Expansion

When looking to diversify the diet of neurodivergent individuals, especially those with restrictive eating, a technique called ‘food chaining’ can be remarkably effective. This approach involves making tiny, incremental changes that don’t feel overwhelming, ensuring that the individual’s existing ‘safe foods’ are respected and integrated. The goal is slow, sustainable progress, not immediate dietary perfection.

Consider an individual who consistently eats fast-food beef burgers. The first step in food chaining might involve simply buying one of these preferred burgers but swapping out the bun for a different, perhaps slightly more nutritious, type. Once that change is accepted and comfortable, the next step could be to introduce a similar supermarket burger option, gradually moving towards a homemade version, and eventually, eating the burger without any bun at all. Each step is small, building confidence without creating anxiety.

Another practical example involves a favorite meal like pasta with tomato sauce and cheese. A food chaining strategy could introduce a small percentage—say, 10%—of a higher-protein, pea-based pasta in the same shape, mixed in with the regular pasta. Over time, this percentage can be slowly increased. This method subtly enhances the nutritional value of the meal without drastically altering the sensory experience.

Crucially, success hinges on maintaining visual familiarity and making changes at an individual’s own pace. If a food looks or tastes too different too quickly, it can be profoundly anxiety-inducing for neurodivergent individuals, particularly those with autism or ARFID. The principle is to reduce the number of sensory challenges at any given moment, making each step manageable and affirming.

13. Unconventional Combinations: Redefining ‘Normal’ to Maximize Nutrition

When supporting neurodivergent individuals with restrictive eating challenges, it’s often necessary to discard conventional ‘food rules’ and embrace seemingly ‘bizarre’ food combinations. The primary objective is to get essential nutrients into the body in a way that is acceptable and comfortable for the individual, even if it deviates from typical culinary norms. This flexible mindset can unlock new nutritional possibilities.

For example, a client might insist that everything they eat must be dipped in tomato ketchup. While this might seem unusual, allowing them to eat broccoli dipped in ketchup is undeniably better than not eating broccoli at all. Similarly, if someone finds comfort in banana and Marmite sandwiches, and the Marmite helps mask a less preferred taste, then that combination is perfectly fine. The key is using these preferred condiments or ‘key things’ to make other nutritious foods more palatable, and then slowly reducing their quantity over time.

However, a critical ethical consideration is the act of hiding foods. While caregivers may be well-meaning, tricking neurodivergent individuals into eating foods they prefer to avoid can severely erode trust. If an individual discovers that their food was disguised, it can cause significant distress and shatter the foundation of trust, creating challenges they were not prepared for. Openness and collaboration are paramount in building a positive relationship with food.

14. Supportive Strategies for Caregivers: Fostering a Positive Food Environment

For family members and caregivers, supporting a neurodivergent individual through their unique eating patterns requires patience, empathy, and practical strategies. It’s about creating an environment where they feel understood and nourished, rather than pressured or judged. Maya Feller, MS, RD, CDN, offers four invaluable tips to guide this supportive journey.

Firstly, **identify their preferences**. It’s a misconception that all neurodivergent individuals have the same food preferences; like all people, they are unique. Observe which textures (soft, crunchy, pureed), temperatures (hot, cold, warm), and tastes (bland, salty, sweet) they consistently enjoy. This can be done by carefully noting which foods they finish or take small bites of, providing crucial insights into their comfort zones.

Secondly, **modify food options** based on these identified preferences. If a creamy texture is preferred, blend foods with milk or yogurt. For crispy textures without oil, an air fryer or oven can be used. Temperatures can be adjusted by cooling hot foods with an ice bath or ice cubes, or heating cold items. If bland foods are favored, limit strong seasonings, sauces, or acids; conversely, increase them for those who enjoy robust flavors.

Thirdly, **examine the mealtime environment**. Many neurological conditions, especially autism, involve sensory sensitivities that can make mealtime overwhelming. Observe what stimuli might be distracting or irritating—bright lights, background noise, or even specific smells. Removing these stressors, such as eating in a dimly lit room or turning off noisy appliances, can significantly improve focus and comfort during meals. If possible, directly ask the individual what would make their mealtime experience better.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, **offer, never force, new foods**. While it’s natural to want to introduce a wide variety of healthy options, the focus should remain on a balanced diet incorporating foods from all groups that the individual already knows and loves. Presenting new foods as an option, without pressure, allows them to experience and choose at their own pace. It might take days, weeks, or months, but providing gentle encouragement and adapting to their needs will help foster a healthy brain and body, letting them know it is okay to eat differently.

The journey to a healthy and positive relationship with food for neurodivergent individuals is often complex, but it is deeply rewarding. It’s about recognizing that ‘different wiring’ doesn’t mean ‘broken,’ but rather requires tailored and compassionate approaches. By focusing on targeted nutritional support, implementing flexible and respectful eating strategies like food chaining and unconventional combinations, and empowering caregivers with actionable techniques, we can build sustainable solutions. Embracing curiosity over fear, nourishment over restriction, and autonomy over external pressures allows for a gentler, more effective path to well-being. Small, manageable changes, profoundly tailored to individual needs, can indeed lead to significant improvements in energy, focus, and overall quality of life, affirming that everyone deserves to feel confident and relaxed around food.