Pennsylvania, officially designated as the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, stands as a pivotal U.S. state, bridging the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It is a land of rich geographical diversity, spanning 170 miles (274 km) from north to south and 283 miles (455 km) from east to west. Its borders are distinct: Delaware to the southeast, Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, and Ohio and the Ohio River to its west. To the north, it meets Lake Erie and New York, while the Delaware River and New Jersey define its eastern boundary, and the Canadian province of Ontario lies to its northwest across Lake Erie. This unique positioning has historically placed Pennsylvania at the crossroads of American development, influencing its culture, economy, and political landscape profoundly.

As of the 2020 United States census, Pennsylvania is home to over 13 million residents, making it the fifth-most populous U.S. state. It also ranks ninth in population density and thirty-third in land area among all states. The state’s most populous city is Philadelphia, a historical nexus that anchors the southeastern Delaware Valley, the largest metropolitan statistical area and the nation’s sixth-most populous city. Further west, Greater Pittsburgh, centered around Pittsburgh, stands as the state’s second-largest metropolitan area. Harrisburg serves as the capital of this diverse and influential commonwealth.

Pennsylvania’s deep historical roots stretch back millennia before its colonial foundation. Archaeologists suggest that human habitation in the Americas began at least 15,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Period, though the precise timeline for human presence in present-day Pennsylvania remains unconfirmed. Significant evidence of ancient civilizations exists at Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Jefferson Township, marking it as potentially the earliest known site of human activity in Pennsylvania, and perhaps all of North America. This site reveals remains of a civilization that thrived over 10,000 years ago, possibly predating the well-known Clovis culture. By 1000 AD, the nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles of Pennsylvania’s native populations had evolved, giving way to advanced agricultural techniques and the establishment of a mixed food economy.

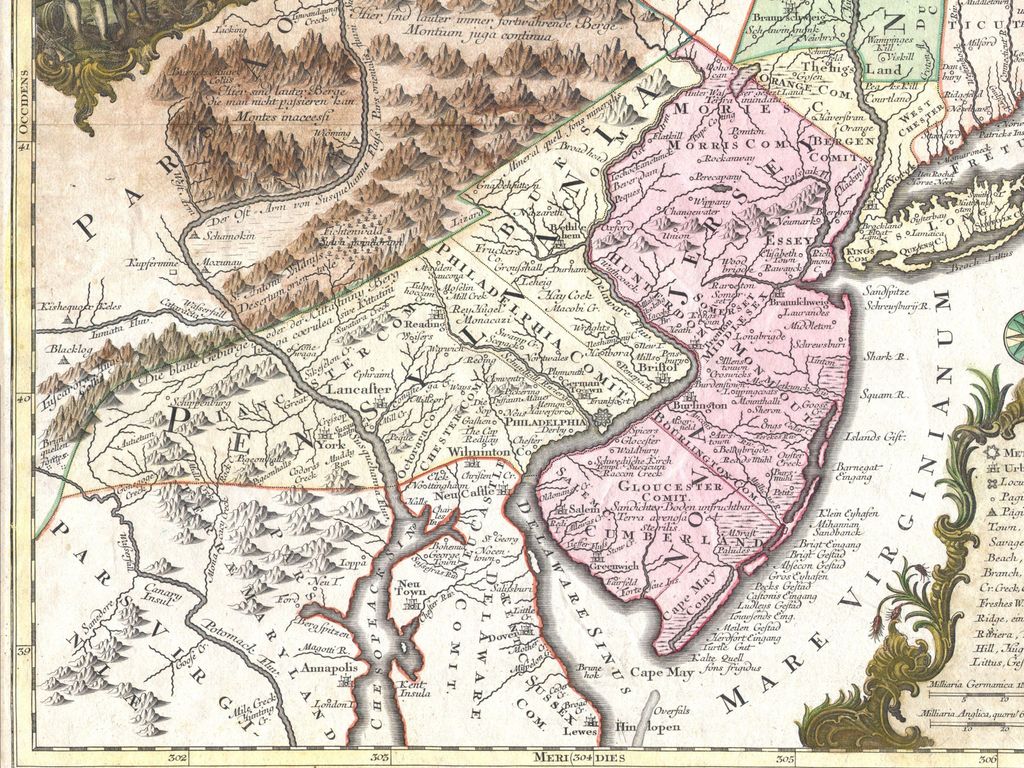

Upon the arrival of European colonizers, at least two prominent Native American tribes inhabited the lands that would become Pennsylvania. The Lenape, speakers of an Algonquian language, occupied the eastern region, then known as Lenapehoking. This extensive territory encompassed most of present-day New Jersey and the Lehigh Valley and Delaware Valley regions in eastern and southeastern Pennsylvania, extending westward to an unspecified point between the Delaware River and the Susquehanna River. The Susquehannock, an Iroquoian-speaking tribe, were concentrated in Eastern Pennsylvania along the Susquehanna River. Both tribes faced severe challenges from European diseases and relentless warfare with neighboring tribes and European groups, leading to their decline. Their financial stability was also compromised as the Hurons and Iroquois prevented their westward expansion into Ohio during the Beaver Wars. As their numbers dwindled and lands were lost, the Hurons retreated closer to the Susquehanna River, while the Iroquois and Mohawk tribes migrated further north. Northwest of the Allegheny River lived the Iroquoian Petun, who fragmented into three distinct groups during the Beaver Wars: the Petun of New York, the Wyandot of Ohio, and the Tiontatecaga of the Kanawha River in southern West Virginia. South of the Allegheny River was a nation known as Calicua, potentially linked to the Monongahela culture.

The 17th century marked the beginning of European colonial claims over the Delaware River region, with both the Dutch and the English asserting dominion. The Dutch were the initial European power to establish a foothold, initiating settlement of the Delmarva Peninsula on June 3, 1631, with the Zwaanendael Colony at what is now Lewes, Delaware. In 1638, Sweden followed suit, establishing the New Sweden Colony near Fort Christina, present-day Wilmington, Delaware. New Sweden claimed and largely controlled the lower Delaware River region, encompassing parts of modern-day Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, though it saw limited European settlement. This period of dual claims set the stage for subsequent conflicts and shifts in power among European colonizers.

England’s assertions over these lands escalated on March 12, 1664, when King Charles II granted James, Duke of York, a vast territory that conflicted directly with Dutch claims in New Netherland, which included portions of present-day Pennsylvania. Shortly thereafter, on June 24, 1664, the Duke of York sold a segment of this grant, encompassing present-day New Jersey, to John Berkeley and George Carteret, establishing a proprietary colony. Although the land was not yet under British control, this sale effectively encircled the Dutch-held territory on the western bank of the Delaware River. The British conquest of New Netherland commenced on August 29, 1664, with the coerced surrender of New Amsterdam, followed by the capture of Fort Casimir in what is now New Castle, Delaware, in October 1664. The Treaty of Breda, signed on July 21, 1667, officially confirmed the English conquest, despite temporary reversions during subsequent conflicts.

A brief Dutch resurgence occurred on September 12, 1672, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War, as they reconquered New York Colony/New Amsterdam and established three County Courts, including Upland, which would later transfer to Pennsylvania. However, the Treaty of Westminster on February 9, 1674, ended the war and restored the political situation to the status quo ante bellum. The British retained the Dutch Counties, initially with their original names. By June 11, 1674, New York reasserted control, and by November 11, 1674, the names began to be Anglicized. Significantly, Upland was partitioned on November 12, 1674, creating the foundational outline for the present-day border between Pennsylvania and Delaware.

The formal founding of the colonial Province of Pennsylvania occurred on February 28, 1681, when King Charles II granted a land charter to William Penn, a prominent Quaker leader and son of a distinguished admiral. This substantial grant, made to repay a debt of £16,000 (approximately £2,100,000 in 2008, adjusted for retail inflation) owed to Penn’s father, stands as one of the largest land grants ever given to an individual. Penn initially proposed naming the land New Wales, but objections led him to suggest Sylvania, derived from the Latin “silva” meaning “forest, woods.” The King, in turn, named it Pennsylvania—literally “Penn’s Woods”—in honor of Admiral Penn. The younger Penn, reportedly embarrassed by the perception that he had named it after himself, was unable to persuade the King to change it. Penn’s foresight led to the establishment of a government incorporating two significant innovations: the county commission and guaranteed freedom of religion, principles that were subsequently adopted by many of the other Thirteen Colonies.

Upon the institution of Pennsylvania’s colonial governments on March 4, 1681, the area previously known as Upland on the Pennsylvania side of the Pennsylvania-Delaware border was renamed Chester County. A pivotal moment in the colony’s early history was William Penn’s signing of a peace treaty with Tamanend, the leader of the Lenape tribe. This act initiated a long era of amicable relations between the Quakers and the Native American tribes, distinguishing Pennsylvania from many other colonial ventures. Additional treaties between Quakers and other tribes further solidified these peaceful bonds, most notably the Treaty of Shackamaxon, which, as historical accounts attest, was never violated.

The 18th century in Pennsylvania was marked by economic innovation, educational advancement, and its critical role in the American Revolution. Between 1730 and 1764, when the Pennsylvania Colony was subjected to the British Parliament’s Currency Act, it uniquely issued its own paper money, known as Colonial Scrip, to address a shortage of gold and silver currency. These bills of credit, endowed with legal tender status, were considered as valuable as gold or silver coins. Their governmental issuance, rather than by banking institutions, rendered them interest-free, significantly reducing the financial burden on the government and, consequently, the taxation of its citizens. This currency system fostered widespread employment and prosperity, as the government carefully managed its issuance to prevent inflation. Benjamin Franklin, instrumental in its creation, lauded its undisputed utility, and even Adam Smith offered it “cautious approval.”

Franklin’s contributions extended beyond currency. In 1740, he founded the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, making it the first college established in Pennsylvania and one of the earliest in the nation. This institution, one of the nine colonial colleges, has since evolved into an Ivy League university, consistently recognized among the world’s leading academic centers. Following the Revolutionary War and the unification of the states, Dickinson College in Carlisle was founded in 1773 by Benjamin Rush, named in honor of John Dickinson. Its establishment was formally ratified on September 9, 1783, a mere five days after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, underscoring the new nation’s commitment to education.

Challenges to peace also emerged in the mid-18th century. James Smith documented that in 1763, “the Indians again commenced hostilities, and were busily engaged in killing and scalping the frontier inhabitants in various parts of Pennsylvania. This state was then a Quaker government, and at the first of this war the frontiers received no assistance from the state.” These hostilities escalated into what became known as Pontiac’s War. Despite the Quaker government’s pacifist stance, the realities of frontier life often necessitated defense.

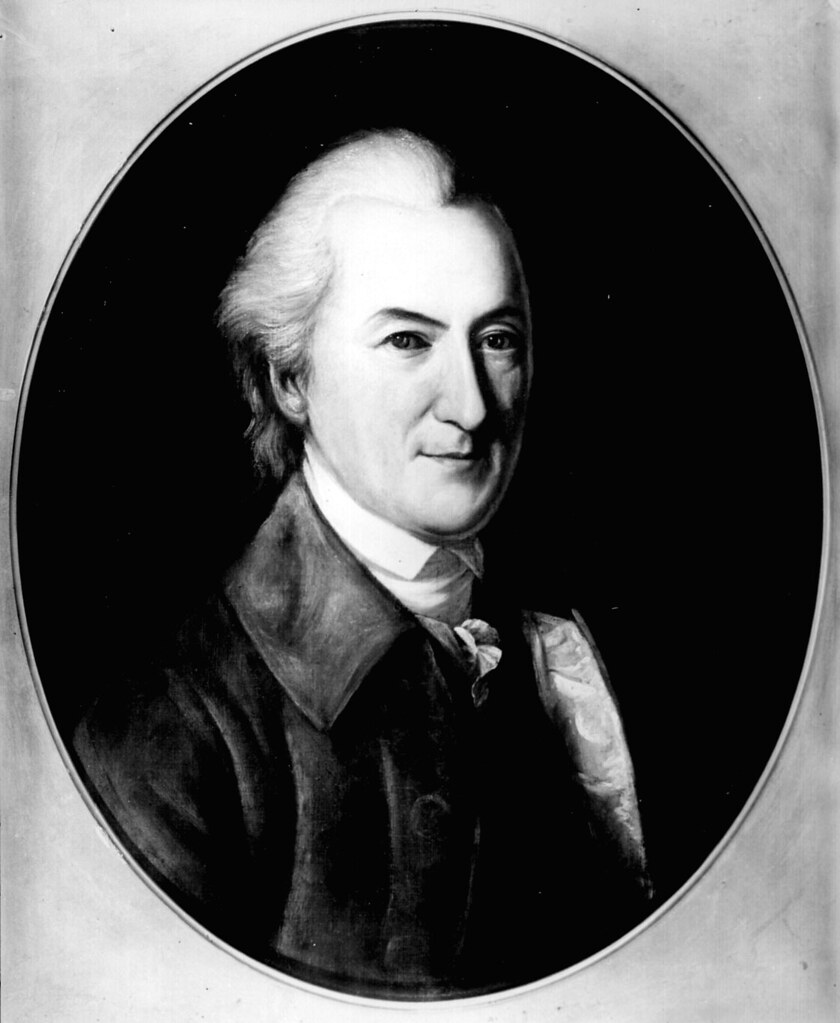

Pennsylvania’s role in shaping the American identity during the lead-up to the Revolution was monumental. After the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, John Dickinson, a delegate from Philadelphia, authored the influential Declaration of Rights and Grievances. This Congress, convened at the request of the Massachusetts assembly, was the inaugural meeting of the Thirteen Colonies, with nine of them sending delegates. Dickinson further articulated colonial grievances and principles in his “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, To the Inhabitants of the British Colonies,” published in the Pennsylvania Chronicle between December 2, 1767, and February 15, 1768. These writings galvanized colonial sentiment against British policies.

Philadelphia became the very cradle of the new nation when the Founding Fathers gathered there in 1774 for the First Continental Congress, attended by representatives from 12 colonies. The Second Continental Congress, commencing in May 1775, notably authored and signed the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. This assembly also formed the Continental Army in 1775, placing it under the command of George Washington. When Philadelphia succumbed to British forces during the Philadelphia campaign, the Continental Congress relocated westward, first convening at the Lancaster courthouse on Saturday, September 27, 1777, and subsequently moving to York. It was in York that the Second Continental Congress adopted the Articles of Confederation, largely drafted by Pennsylvania delegate John Dickinson, which bound the 13 independent states into a nascent union. Later, Philadelphia was again chosen as the birthplace for the new nation’s guiding document, the U.S. Constitution. The Constitution was drafted and signed at the Pennsylvania State House, now revered as Independence Hall—the very same building where the Declaration of Independence was adopted and signed in 1776.

Pennsylvania was the second state to ratify the U.S. Constitution on December 12, 1787, following Delaware by just five days. At this time, Pennsylvania was notable for being the most ethnically and religiously diverse of the thirteen colonies. Reflecting its substantial German-speaking population—comprising a third of its residents—the Constitution was translated into German to ensure broad public participation in the discourse surrounding its ratification. Reverend Frederick Muhlenberg, a Lutheran minister who later became the first Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, presided as chairman of Pennsylvania’s ratifying convention, a testament to the state’s commitment to inclusive governance. For half a century, the Pennsylvania General Assembly convened at various sites in the Philadelphia area before settling into a consistent 63-year tenure at Independence Hall. However, significant events like the Paxton Boys massacres of 1763 underscored the necessity for a centrally located capital. Consequently, in 1799, the General Assembly relocated to the Lancaster Courthouse.

The 19th century witnessed Pennsylvania’s transformation through the throes of the American Civil War and the explosive growth of industrialization. The Pennsylvania General Assembly met in the old Dauphin County Court House until December 1821. It then moved to the Federal-style Hills Capitol, designed by Lancaster architect Stephen Hills, constructed on a four-acre hilltop land grant in Harrisburg. This land had been set aside for the seat of state government by the son and namesake of John Harris Sr., a Yorkshire native who established a trading post and ferry on the east shore of the Susquehanna River in 1705. Tragically, the Hills Capitol was destroyed by fire on February 2, 1897, during a heavy snowstorm, likely due to a faulty flue.

Following the fire, the General Assembly temporarily convened at a nearby Methodist Church while plans for a new capitol proceeded. An initial architectural competition led to Chicago architect Henry Ives Cobb being tasked with designing a replacement. However, due to limited funding, the resulting Cobb Capitol building was roughly finished and industrial in appearance, prompting the legislature to refuse to occupy it. Public outcry and political indignation in 1901 spurred a second competition, this time restricted to Pennsylvania architects. Joseph Miller Huston of Philadelphia was ultimately chosen to design the current Pennsylvania State Capitol, integrating Cobb’s existing structure into a magnificent public work. The current capitol was finally completed and dedicated in 1907, symbolizing the state’s resilience and ambition. The mid-19th century also saw a Pennsylvanian ascend to the nation’s highest office: James Buchanan, a native of Franklin County, served as the 15th U.S. president from 1857 to 1861, becoming the first president born in Pennsylvania.

A defining moment in American history, the Battle of Gettysburg, raged for three days from July 1 to July 3, 1863, near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. This engagement proved to be the deadliest battle of the American Civil War and indeed, of any battle in American military history, resulting in over 50,000 Union and Confederate fatalities. The Union army’s decisive victory at Gettysburg marked a crucial turning point in the Civil War, repelling the Confederacy’s invasion of the North and ultimately paving the way for the Union’s triumph two years later and the preservation of the nation. Several months later, on November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln traveled to Gettysburg to participate in a ceremonial consecration of the present-day Gettysburg National Cemetery. There, he delivered the Gettysburg Address, a concise 271-word speech now regarded as one of the most famous speeches in American history. During the Civil War, an estimated 350,000 Pennsylvanians served in the Union army, including 8,600 African American military volunteers, underscoring the state’s significant contribution to the war effort.

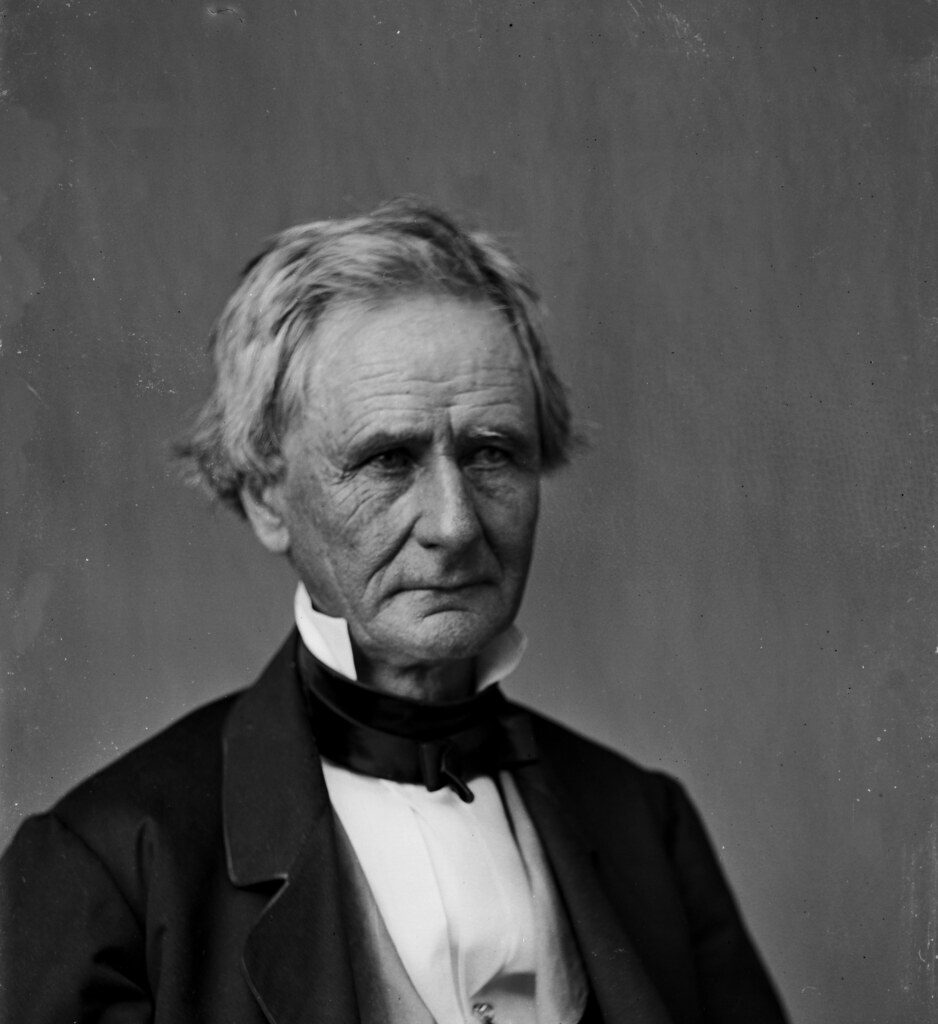

Politically, Pennsylvania was for decades dominated by the financially conservative Republican-aligned Cameron machine, established by U. S. Senator Simon Cameron, who later served as Lincoln’s Secretary of War. Control of this influential political machine eventually transferred to Cameron’s son, J. Donald Cameron, whose perceived ineffectiveness led to a shift in power to Matthew Quay and subsequently to Boies Penrose. The post-Civil War era, often referred to as the Gilded Age, saw an accelerated rise of industry across Pennsylvania.

The state became home to some of the world’s largest steel companies, with Andrew Carnegie founding the Carnegie Steel Company in Pittsburgh and Charles M. Schwab establishing Bethlehem Steel in Bethlehem. Other titans of industry, including John D. Rockefeller and Jay Gould, also operated within Pennsylvania’s borders, leveraging its vast resources. The U. S.

oil industry, for instance, was born in Western Pennsylvania during the latter half of the 19th century, supplying the vast majority of kerosene for years. The Pennsylvania oil rush led to the rise and eventual decline of boom towns like Titusville. Coal mining, predominantly in the state’s Coal Region in the northeast, also served as a major industry throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1903, Milton S. Hershey began constructing a chocolate factory in Hershey, Pennsylvania, which would grow into The Hershey Company, North America’s largest chocolate manufacturer.

The Heinz Company was also founded during this period, adding to the state’s industrial prowess. These massive corporations exerted considerable influence on Pennsylvania politics, as Henry Demarest Lloyd famously noted of oil baron John D. Rockefeller: he “had done everything with the Pennsylvania legislature except refine it. ” To support this industrial expansion, Pennsylvania created a Department of Highways and embarked on an extensive program of road-building, while railroads continued to see heavy usage, facilitating the movement of goods and people.

The burgeoning industrial landscape eventually provided middle-class incomes to working-class households, largely due to the development of labor unions that helped workers secure living wages. However, the rise of unions also precipitated increased union busting, marked by the emergence of several private police forces designed to suppress labor movements. Pennsylvania holds the distinction of being the site of North America’s first documented organized strike. The state was also the setting for two hugely prominent labor disputes: the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Coal Strike of 1902, both of which highlighted the intense struggles between labor and capital. Over time, significant labor reforms were achieved, including the adoption of the eight-hour workday and the eventual banning of the coal and iron police forces, reflecting a slow but steady progress in workers’ rights.

At the dawn of the 20th century, Pennsylvania’s economy was robustly centered on steel manufacturing, logging, coal mining, textile production, and various other forms of industrial manufacturing. A substantial surge in immigration to the U.S. during the late 19th and early 20th centuries ensured a continuous supply of cheap labor for these industries, which frequently employed children and non-English speaking individuals from Southern and Eastern Europe. Thousands of Pennsylvanians volunteered for service during the Spanish–American War, demonstrating the state’s patriotic commitment. Pennsylvania’s role as a vital industrial center became even more pronounced during World War I, with over 300,000 of its soldiers serving in the conflict. A significant diplomatic event also occurred in the state on May 31, 1918, when the Pittsburgh Agreement was signed in Pittsburgh by Tomáš Masaryk, leading to the establishment of Czechoslovakia as an independent nation. In 1922, a major labor action saw 310,000 Pennsylvania miners participate in the UMW General coal strike, a prolonged dispute lasting 163 days that effectively shut down most of the state’s coal mines.

Conservation efforts gained traction in 1923 when President Calvin Coolidge established the Allegheny National Forest under the authority of the Weeks Act of 1911. Located in the northwest part of the state, spanning Elk, Forest, McKean, and Warren Counties, the forest was designated for timber production and watershed protection in the Allegheny River basin. It remains the state’s sole national forest. During World War II, Pennsylvania’s industrial might was again critical to the nation’s defense; the state manufactured 6.6 percent of total U.S. military armaments for the war, ranking sixth among the 48 states. The Philadelphia Naval Shipyard served as an important naval base, and Pennsylvania produced many of the war’s most influential military leaders, including George C. Marshall, Hap Arnold, Jacob Devers, and Carl Spaatz. Over a million Pennsylvanians served in the armed forces during World War II, and more Medals of Honor were awarded to individuals from Pennsylvania than from any other state, highlighting its extraordinary contribution to the war effort.

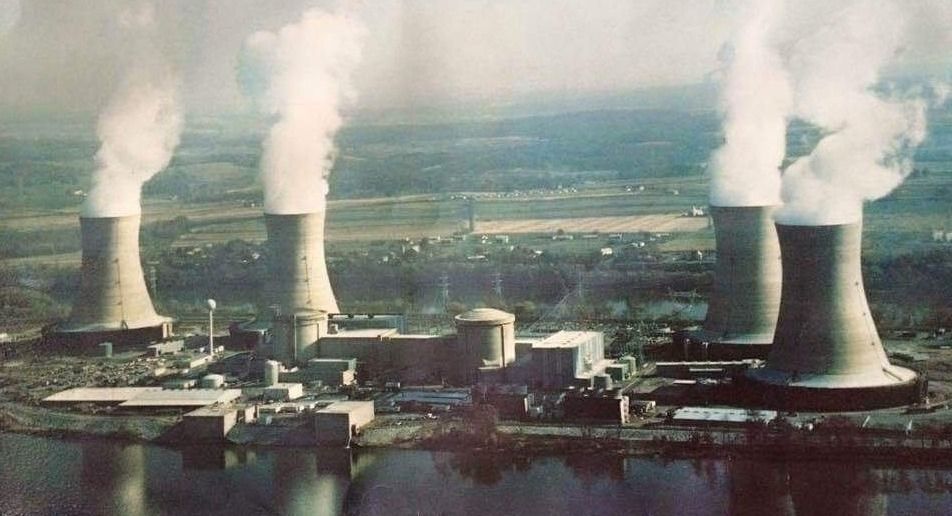

The latter half of the 20th century presented new challenges and shifts for Pennsylvania. On March 28, 1979, the Three Mile Island accident occurred, marking the most significant nuclear accident in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant history, drawing national and international attention. The state was particularly hard-hit by the decline and subsequent restructuring of its steel and other heavy industries during the late 20th century. This industrial downturn led to substantial job losses and a significant out-migration of population, especially from the state’s largest cities. Pittsburgh, once a top ten most populous city in the United States in 1950, lost its standing, while Philadelphia, after decades of ranking among the top three, dropped to fifth and is currently the sixth-largest city. After 1990, as information-based industries began to gain economic importance, state and local governments began allocating more resources to the well-established public library system. However, some localities utilized new state funding to reduce local taxes instead of reinvesting in public services. Concurrently, new ethnic groups, particularly Hispanics and Latinos, began migrating into the state to fill low-skill jobs in agriculture and service industries. For example, in Chester County, Mexican immigrants brought the Spanish language, increased Catholicism, high birth rates, and new cuisine as they were hired as agricultural laborers; in some rural areas, they constituted half or more of the local population. Stateside Puerto Ricans have also established a significant community in Allentown, the state’s third-largest city, where they comprised over 40% of the city’s population as of 2000.

In the late 20th century, as Pennsylvania’s historical leadership in mining largely ceased and its steelmaking and other heavy manufacturing sectors experienced a slowdown, the state strategically sought to bolster its service and other industries to compensate for the lost jobs and economic productivity. Pittsburgh, leveraging its concentration of universities, has emerged as a leader in technology and healthcare. Similarly, Philadelphia benefits from a strong concentration of university expertise, contributing to its diverse economy. Healthcare, retail, transportation, and tourism have become some of the state’s burgeoning industries in the post-industrial era. Consistent with national trends, most residential population growth has occurred in suburban rather than central city areas, though both Philadelphia and Pittsburgh have experienced significant revitalization in their downtown districts. Philadelphia anchors the country’s seventh-largest metropolitan area and one of the world’s largest, while Pittsburgh serves as the center of the nation’s 27th-largest metropolitan area. As of 2020, the Lehigh Valley in eastern Pennsylvania ranked as the nation’s 69th-largest metropolitan area. Beyond these major hubs, Pennsylvania also boasts six additional metropolitan areas among the nation’s 200-most populous. Philadelphia is integral to the Northeast megalopolis and is generally associated with the Northeastern United States, while Pittsburgh is part of the Great Lakes megalopolis and is often linked to the Rust Belt region.

The 21st century has seen Pennsylvania continue to play a role in national and global events. During the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States, the small town of Shanksville, Pennsylvania, garnered worldwide attention. United Airlines Flight 93 crashed into a field in Stonycreek Township, located 1.75 miles (2.82 km) north of the town, after passengers heroically revolted against the Al-Qaeda hijackers. All 40 civilians and 4 hijackers on board perished. The hijackers’ initial intention was to crash the plane into either the United States Capitol or The White House. However, after learning from family members via air phone about the earlier attacks on the World Trade Center, Flight 93’s passengers courageously fought for control of the aircraft, causing it to crash before reaching its intended target. This act of heroism has been widely commemorated, ensuring Flight 93 was the only one of the four hijacked aircraft that day that never reached its intended destination. More recently, in October 2018, the Tree of Life – Or L’Simcha Congregation, a conservative Jewish synagogue in Pittsburgh, experienced a tragic shooting, which resulted in 11 fatalities. On July 13, 2024, an assassination attempt on the 45th President of the United States Donald Trump occurred near Butler, Pennsylvania, further marking the state as a site of significant contemporary events.

Pennsylvania’s geography is notably diverse, reflecting its expansive reach across multiple U.S. regions. The state encompasses a total area of 46,055 square miles (119,282 km2), of which 44,817 square miles (116,075 km2) are land, 490 square miles (1,269 km2) are inland waters, and 749 square miles (1,940 km2) are waters within Lake Erie. It holds the distinction of being the 33rd-largest state in the United States. While Pennsylvania lacks an ocean shoreline, it boasts 51 miles (82 km) of coastline along Lake Erie and 57 miles (92 km) of shoreline along the Delaware Estuary, giving it significant waterfront access. Of the original Thirteen Colonies, Pennsylvania stands alone as the only state that does not border the Atlantic Ocean. The state’s boundaries are precisely defined: the Mason–Dixon line (39°43′ N) to the south, the Twelve-Mile Circle on the Pennsylvania-Delaware border, the Delaware River to the east, 80°31′ W to the west, and 42° N to the north, with a small western extension forming a triangle north to Lake Erie. Geographically, the state is segmented into five distinct regions: the Allegheny Plateau, Ridge and Valley, Atlantic Coastal Plain, Piedmont, and Erie Plain, each contributing to its varied landscapes.

The diverse topography of Pennsylvania gives rise to a variety of climates, though the entire state generally experiences cool to cold winters and very warm, humid summers. Positioned across two major climate zones, much of Pennsylvania falls under a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa or Dfb). Conversely, the southern portion of the state, including its largest city, Philadelphia, exhibits a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa). Summers are typically hot and humid throughout the commonwealth. As one moves toward the state’s mountainous interior, winter conditions become colder, the prevalence of cloudy days increases, and snowfall amounts become more significant. Western areas of the state, particularly those situated near Lake Erie, can receive over 100 inches (250 cm) of snowfall annually. The entire state benefits from plentiful precipitation distributed throughout the year. Pennsylvania can also be susceptible to severe weather events from spring through summer into autumn. Tornadoes occur annually, sometimes in considerable numbers—as evidenced by 30 recorded tornadoes in 2011—though violent tornadoes are less frequent than in states further west.

Pennsylvania is home to a robust network of municipalities, ranging from bustling metropolises to historic towns. Prominent cities in the southeastern region include Philadelphia, Reading, Lebanon, and Lancaster. To the southwest lies Pittsburgh, while the tri-cities of Allentown, Bethlehem, and Easton, collectively known as the Lehigh Valley, are situated in the central east. The northeastern part of the state features former anthracite coal mining cities such as Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, Pittston, Nanticoke, and Hazleton. Erie is located in the northwest, and State College anchors the central region. Williamsport is found in the north-central area, with York, Carlisle, and the state capital Harrisburg positioned on the Susquehanna River in the east-central region. In the state’s west-central area are Altoona and Johnstown. The three most populated cities in Pennsylvania, in descending order of size, are Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Allentown, reflecting distinct population centers across the commonwealth.

Demographically, Pennsylvania presents a compelling portrait of evolution and diversity. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the state’s population stood at 13,011,844, representing an increase from 12,702,379 in 2010. This makes Pennsylvania the fifth-most populated state in the U.S., trailing only California, Texas, Florida, and New York. In 2019, while net migration to other states resulted in a decrease of 27,718 residents, immigration from other countries contributed a significant increase of 127,007, leading to a net migration gain of 98,289 to Pennsylvania. However, migration of native Pennsylvanians resulted in a decrease of 100,000 people. As of 2021, 7.2% of the population was foreign-born. The state’s center of population is located in Duncannon in Perry County. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, an estimated 12,691 homeless people resided in Pennsylvania, highlighting ongoing societal challenges.

The racial and ethnic composition of Pennsylvania’s population is largely made up of whites, blacks, and Hispanics, with the latter two constituting significant minority populations. Non-Hispanic Whites form the majority of Pennsylvania’s populace, with most descending from German, Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Italian, and English immigrants. Rural areas of South Central Pennsylvania are nationally recognized for their distinctive Amish communities, preserving a unique cultural heritage. The Wyoming Valley, encompassing Scranton and Wilkes-Barre, stands out with the highest percentage of white residents—96.2% claiming white, non-Hispanic background—among any metropolitan area in the U.S. with a population of 500,000 or above. The state’s Hispanic or Latino American population experienced remarkable growth, increasing by 82.6% between 2000 and 2010, marking one of the largest increases in a state’s Hispanic population. This significant demographic shift is primarily attributed to migration from Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory, and to a lesser extent, immigration from countries such as the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and various Central and South American nations, alongside a notable wave of Hispanic and Latinos relocating from New York City and New Jersey in search of more affordable living. The majority of Hispanic or Latino Americans in Pennsylvania are of Puerto Rican descent, with Mexicans and Dominicans making up most of the remaining Hispanic or Latino population.

From its foundational commitment to religious freedom and peaceful relations with native tribes, through its indispensable role in the American Revolution, and across centuries of industrial innovation and demographic evolution, Pennsylvania has consistently served as a microcosm of the broader American experience. It is a state where the echoes of colonial struggles and Civil War battles resonate with the hum of modern industry and the vibrancy of diverse communities. The narratives woven into its landscapes and cities—from the historic halls of Philadelphia to the industrial heartland of Pittsburgh, and the tranquil farmlands of Amish country—collectively tell a story of constant adaptation and enduring significance. As Pennsylvania navigates the complexities of the 21st century, its rich tapestry of history, geography, and human experience continues to shape not just its own destiny, but also contributes profoundly to the ongoing American narrative.