Ever felt like some words just… change? One day they mean one thing, the next, they’re on a whole different journey. Well, buckle up, because few terms have shapeshifted as dramatically, or sparked as much debate, as ‘cult.’ What started as a fairly straightforward idea blossomed into a complex, often charged concept, leaving a fascinating trail of intellectual history in its wake. It’s like looking back at those beloved, quirky small trucks that once filled our roads – the ones that, for various reasons, just aren’t around in the same way anymore. But instead of chrome and horsepower, we’re talking about big ideas and academic heavyweights!

Seriously, the journey of understanding ‘cults’ is a wild ride through sociology, religion, and pop culture, filled with twists, turns, and some seriously groundbreaking insights that have influenced how we perceive groups with unusual beliefs. Many of the definitions and classifications we take for granted today were once cutting-edge ideas, debated fiercely by scholars. It’s a bit like recalling the era when everyone knew exactly what a ‘mini truck’ was, before the landscape changed. These concepts were the workhorses of academic discourse, shaping how researchers approached everything from new religious movements to societal tensions.

So, get ready for a nostalgic trip down memory lane, or perhaps, a fascinating introduction to the ideas that once dominated conversations about social groups! We’re digging into the core concepts that defined the study of ‘cults,’ exploring how they came to be, how they evolved, and in some cases, how their prominence or interpretation has shifted over time. Consider this your definitive guide to the foundational ‘cult-favorite’ ideas that helped us make sense of the world. Let’s roll!

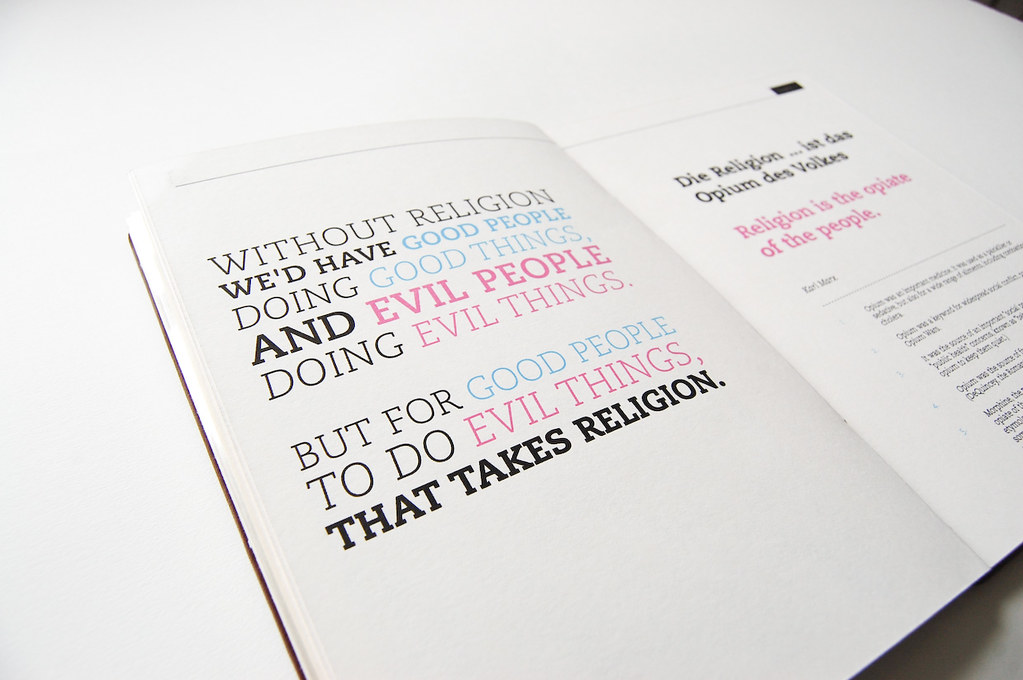

1. **The ‘Cult’ Concept: From Worship to Whisper of Warning**Ah, the word ‘cult’ itself – a true linguistic chameleon! Before it became the loaded term we often hear today, it actually had a much more innocent, dare we say, conventional meaning. Derived from the Latin ‘cultus,’ it simply meant ‘worship.’ In this older sense, it referred to a set of religious devotional practices that were perfectly conventional within a culture, often associated with a particular figure or place, or simply the collective participation in religious rites. Think of the imperial cult of ancient Rome; the word was used without any negative baggage whatsoever.

Fast forward to modern English, and *bam!* The term ‘cult’ lands with a much heavier thud, generally carrying derogatory connotations. It’s become a pejorative, often applied to abusive or coercive groups, and not just religious ones. We’re talking about everything from gangs and organized crime to even terrorist organizations, if the context is right. The transformation from ‘worship’ to ‘warning’ is quite remarkable, isn’t it? It highlights how language itself can evolve to reflect societal anxieties and changing perceptions of social structures.

This shift in meaning has made ‘cult’ a real shapeshifter, as scholar Susannah Crockford notes, semantically morphing “with the intentions of whoever uses it.” It’s weakly defined, with divergent interpretations in both popular culture and academia, leading to ongoing scholarly contention. Crockford argues that the least subjective definition refers to a religion or religion-like group “self-consciously building a new form of society,” a form that the rest of society then rejects as unacceptable. This underlying tension, the ‘us vs. them’ dynamic, is key to its modern usage and much of its controversy.

2. **When Academia Stepped In: The Birth of Sociological Study**Before the term ‘cult’ was flung around with such ease, there was a concerted effort to understand new religious movements academically. It wasn’t until the 1930s that these movements, often perceived as cults, truly became an object of serious sociological study. Imagine a new academic field opening up, full of fresh questions and uncharted territory – it was a really exciting time for scholars trying to make sense of evolving religious behaviors. This era truly marked the beginning of a more structured approach to what had previously been a nebulous, often misunderstood phenomenon.

At the heart of this burgeoning field was the monumental work of sociologist Max Weber. If you’re talking about the academic study of cults, you simply can’t skip over Weber! He laid down some incredibly important theoretical groundwork. His ideas about charismatic authority, for example, were crucial in understanding how leaders could attract and maintain such intense devotion within these groups. It’s a concept that helps explain the allure and power dynamics often associated with the leaders of many new movements.

But Weber didn’t stop there. He also gave us the crucial distinction between churches and sects. This wasn’t just academic hair-splitting; it provided a framework for categorizing religious organizations based on their relationship with the broader society and their approach to membership. This foundational work by Weber became the bedrock upon which future scholars would build, attempting to refine and expand our understanding of how religious and social groups form, operate, and interact with the world around them. What a game-changer!

3. **The Rise of the Christian Countercult Movement: Defending Orthodoxy**Jumping forward a bit to the 1940s, a distinct and organized form of opposition began to coalesce in the United States: the Christian countercult movement. This wasn’t just casual disagreement; it was a structured effort by established Christian denominations to push back against non-Christian religions and any Christian groups they deemed heretical or ‘counterfeit.’ It’s like when a classic, beloved brand sees new competitors pop up and decides to actively defend its turf and core values, but in a theological sense.

For those involved in this movement, the criteria were clear: if a religious group claimed to be Christian but their teachings deviated from what was considered Christian orthodoxy, they were labeled a cult. The movement largely comprised evangelical Protestants, who were deeply committed to their interpretations of biblical truth. They asserted that any Christian group whose teachings didn’t align with the belief that the Bible was inerrant was suspect. This focus on doctrinal purity was a driving force behind their efforts to identify and challenge these groups.

But their scope wasn’t limited to just ‘deviant’ Christian groups. The Christian countercult movement also cast its net wider, focusing on non-Christian religions like Hinduism, which they viewed as equally problematic from their theological standpoint. A key component of their activism was the emphasis on evangelism – they believed it was essential for Christians to actively reach out and evangelize to followers of these perceived ‘cults,’ aiming to bring them back to what they considered the true faith. It was a mission-driven effort rooted in deep conviction.

4. **The Secular Anti-Cult Movement: From Free Will to ‘Brainwashing’**As the 1960s rolled into the 1970s, a new kind of watchdog emerged on the scene, distinct from its Christian counterpart: the secular anti-cult movement (ACM). This wasn’t about theological purity; it was a response to the rapid rise of new religions during that tumultuous era, and particularly catalyzed by shocking events like Jonestown, where nearly a thousand people died. The public was stunned, and families were desperate for answers when their loved ones seemed to drastically alter their lives, seemingly not by their own free will.

These ACM organizations often stepped in on behalf of concerned relatives of ‘cult’ converts. The prevailing question was: how could someone change so completely, so quickly? Many in the movement, including some psychologists and sociologists, began to suggest that standard explanations weren’t enough. They proposed that powerful, coercive psychological techniques, or ‘brainwashing,’ were being used to maintain the loyalty of group members. This theory became a unifying, though controversial, theme.

The ‘brainwashing’ narrative gained significant traction, especially in the mass media and among average citizens. The term ‘cult’ began to take on an even more negative connotation, becoming associated with a terrifying array of issues: kidnapping, psychological abuse, ual abuse, and even mass suicide. While it’s true that some new religious groups had documented instances of these negative qualities, the problem was that mass culture often extended these associations to *any* religious group perceived as culturally deviant, regardless of how peaceful or law-abiding they actually were. This created a lasting, often unfair, stigma.

5. **Weber’s Enduring Legacy: Charismatic Authority and Church vs. Sect**We touched on him earlier, but Max Weber’s contributions are so monumental that they deserve their own spotlight. His work in the academic study of cults is foundational, particularly his brilliant theorizations of charismatic authority and his famous distinction between churches and sects. It’s like stumbling upon the original blueprint for a classic vehicle – you realize just how much thought went into the basic design that everything else was built upon. His insights really laid the groundwork for understanding how these groups functioned and where they fit into society.

Weber’s concept of charismatic authority describes a type of leadership based on the perceived exceptional qualities, charm, or vision of an individual leader. This kind of authority isn’t about tradition or legal rules; it’s about the deep, often emotional, devotion followers have for the leader, believing them to possess unique or even divine powers. This was a crucial lens through which to view many ‘cult’ leaders, explaining their powerful sway over members. It’s a compelling idea that helps explain intense personal loyalty that can defy conventional logic.

His church-sect distinction further organized our understanding of religious movements. A ‘church’ in Weber’s schema is typically a large, inclusive religious body that is well-integrated into the wider society, often seen as the established, mainstream religion. A ‘sect,’ in contrast, is a smaller, more exclusive group that often arises in protest against the church, seeking a return to what it perceives as purer religious practice and maintaining a higher degree of tension with mainstream culture. These distinctions provided vital tools for scholars trying to map the religious landscape, offering categories that went beyond simple labels.

6. **Troeltsch’s Touch: Adding the ‘Mystical’ Dimension**If Weber laid the foundation, German theologian Ernst Troeltsch certainly built an elegant extension onto the theoretical house. Troeltsch took Weber’s groundbreaking church-sect division and elaborated upon it, adding an essential third category: ‘mystical’ religion. This was a significant step forward, acknowledging that religious experience wasn’t always about organized collective worship or sectarian protest. It recognized a different, more personal, and individualistic path to faith that didn’t quite fit the existing molds.

Troeltsch’s ‘mystical’ categorization was designed to accommodate those more personal or individual religious experiences that often transcend formal institutions and dogmas. Think of it as recognizing the solo adventurer in a world of organized expeditions – someone whose journey is deeply personal and less about a group structure. This category allowed for a broader understanding of religious phenomena, moving beyond purely social or institutional forms to include the intimate, inner dimensions of spirituality.

This expansion was vital because it offered a more nuanced framework for sociologists. It highlighted that some groups, or even individuals, might emphasize direct spiritual experience over communal rites or strict doctrinal adherence. By including the mystical, Troeltsch’s typology provided a richer, more comprehensive way to classify religious movements, particularly those that were less formally structured or more focused on esoteric, personal revelations. It truly rounded out the early sociological toolkit for understanding religious behavior.

7. **Becker’s Bifurcation: The Four-Part Typology**Not one to rest on the laurels of his predecessors, American sociologist Howard P. Becker came along and decided to refine the existing frameworks even further. He took Troeltsch’s elaborate church-sect model and bisected the first two categories, giving us an even more granular understanding of religious groups. It’s like taking a well-loved, general-purpose tool and expertly sharpening it into a set of specialized instruments, making it much more precise for specific tasks. Becker truly brought a fresh level of detail to the academic discussion.

Becker’s innovative move was to split the ‘church’ category into two: ‘ecclesia’ and ‘denomination.’ An ecclesia typically refers to a state-recognized, universal religious body, like an official national church, deeply intertwined with societal power. A denomination, on the other hand, is still a large, mainstream religious group, but it exists in a pluralistic society alongside other denominations, without the same exclusive state endorsement. This distinction helped to differentiate between various forms of mainstream religious integration and organization.

He then similarly bisected the ‘sect’ category, splitting it into ‘sect’ and ‘cult.’ In Becker’s framework, a ‘sect’ remained a smaller, more exclusive group that broke away from a larger religious tradition, often maintaining continuity with traditional beliefs but with a more intense commitment and often in tension with society. His ‘cult,’ however, referred specifically to small religious groups that lacked organization and emphasized the private nature of personal beliefs. This last distinction was crucial, creating a specific academic niche for groups that arose spontaneously around novel beliefs, rather than as splinters of existing religions. It was a sophisticated leap forward in classification.”

Okay, so we’ve navigated the wild world of how ‘cults’ became a thing, academically speaking. We’ve seen the big names and the even bigger ideas that tried to pin down these elusive groups. But what happens when these definitions hit the real world? What about the groups that really make headlines, the labels that spark outrage, and how governments around the globe have tried to make sense—or perhaps, control—the ‘cult’ phenomenon? Get ready, because the next leg of our journey dives into the controversies, the distinct types, and the global reactions that have shaped public perception and policy around groups labeled ‘cults.’ It’s a bumpy road, but someone’s gotta drive!

8. **”Destructive Cults”: A Loaded Label and Its Critics**If there’s one phrase that can send a shiver down your spine and instantly color your perception of a group, it’s “destructive cult.” This term, frequently championed by the anti-cult movement, isn’t just a label; it’s a warning, implying a sinister core. These movements typically define a destructive cult as a group that’s unethical, deceptive, and one that wields “strong influence” or even mind-control techniques to hijack critical thinking skills. It’s not just about unusual beliefs; it’s about actual, quantifiable harm.

Sometimes, the anti-cult movement tries to draw a line in the sand, contrasting a “destructive cult” with a “benign cult,” as if some cults are just quirky neighbors with odd rituals. But let’s be real, others just slap the “destructive” label onto any group they deem problematic. For psychologist Michael Langone, who’s the executive director of the anti-cult group International Cultic Studies Association, the definition is pretty stark: a destructive cult is “a highly manipulative group which exploits and sometimes physically and/or psychologically damages members and recruits.” No ambiguity there!

The picture gets even more intense when we consider Eli Shapiro’s take. He sees destructive cultism as a “sociopathic syndrome” that comes with a whole host of alarming qualities. We’re talking about profound behavioral and personality changes, the unsettling loss of personal identity, the abrupt halt of academic pursuits, and a deeply painful estrangement from family. And, perhaps most chillingly, a profound disinterest in society, coupled with the pronounced mental control and enslavement wielded by cult leaders. Sounds pretty heavy, right?

But here’s the kicker: not everyone is on board with flinging the “destructive cult” label around so freely. Many researchers have actually criticized the term, pointing out that it’s often used to describe groups that aren’t necessarily harmful, either to themselves or to others. John A. Saliba, for instance, argues that the term is ridiculously overgeneralized. He suggests that when people use “destructive cult,” they’re usually thinking of the Peoples Temple as the “paradigm,” and unfairly implying that other groups will also commit mass suicide. Talk about a guilt-by-association problem!

Then there’s the nuanced observation from Julius H. Rubin, who, in his book *Misunderstanding Cults*, notes that America’s fertile ground for religious innovation has simply birthed “an unending diversity of sects.” These “new religious movements…gathered new converts and issued challenges to the wider society,” often leading to controversy and litigation. Even Lorne L. Dawson, writing in *Cults in Context*, observes that while the Unification Church “has not been shown to be violent or volatile,” it was still branded a destructive cult by “anticult crusaders.” It just goes to show how much power a label can have, sometimes without the facts to back it up. Even the German government found itself in hot water when, in 2002, it was held by the Federal Constitutional Court to have defamed the Osho movement by referring to it as a “destructive cult” without factual basis.

Read more about: Beyond the Buzzword: Everything You NEED to Know About Cults, From Academia to Global Headlines!

9. **Doomsday Cults: Predicting and Provoking the Apocalypse**If there’s one type of group that consistently captures the public imagination – and sometimes, dread – it’s the doomsday cult. These are the groups that are all about apocalypticism and millenarianism, deeply rooted in the belief that a cataclysmic end of the world is just around the corner, or perhaps, that a golden age is dawning after a major upheaval. The term is quite broad, covering not only those who simply *predict* disaster but also, chillingly, those who actively *attempt to bring it about*. It’s a concept that touches on humanity’s deepest fears and hopes.

Back in the 1950s, a team of American social psychologists, led by the legendary Leon Festinger, got up close and personal with one such group. They spent several months observing members of a small UFO religion known as the Seekers. This wasn’t just a casual observation; they recorded conversations both before and after a prophecy from the group’s charismatic leader failed spectacularly. The whole fascinating (and, let’s be honest, kinda awkward) ordeal was later immortalized in their seminal book, *When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World*.

Fast forward to the late 1980s, and suddenly doomsday cults were everywhere in the news cycle. You couldn’t turn on the TV or pick up a newspaper without seeing reporters and commentators breathlessly discussing them as a serious threat to society. It was a period of heightened anxiety, and these groups, with their dire predictions and often isolated communities, seemed to embody a palpable sense of unease about the future.

What compels people to embrace such a cataclysmic worldview? A 1997 psychological study by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter offered some compelling insights. They found that individuals often turned to these extreme beliefs after repeatedly failing to find meaning, purpose, or connection within mainstream movements or conventional society. It’s a poignant reminder that for some, the apocalypse isn’t just an end; it’s a new beginning, or at least, a desperate search for significance.

10. **Beyond Religion: The World of Political and Other Cults**While our discussion has mostly revolved around religious or spiritual groups, the term “cult” isn’t exclusively reserved for those seeking divine enlightenment or predicting the end times. Oh no, the “cult” concept has proven itself to be quite the versatile little number, making its way into the realm of pure power and ideology. Welcome to the world of “political cults,” groups primarily defined by their intense devotion to political action and ideology. And trust us, they can be just as, if not more, intense than their spiritual cousins!

Journalists and scholars have certainly taken notice, shining a spotlight on groups that some have described as political cults, particularly those advocating extreme far-left or far-right agendas. These aren’t just passionate political movements; they often exhibit the same characteristics we’ve come to associate with cults, like charismatic leadership, fervent ideology, and an “us vs. them” mentality that brooks no dissent. If you’re curious for a deep dive, check out Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth’s 2000 book, *On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left*. They discuss about a dozen organizations in the United States and Great Britain that fit this very specific, and often unsettling, description.

But wait, there’s more! Sociologists William Sims Bainbridge and Rodney Stark, always pushing the envelope, argued for an even further distinction, identifying three distinct kinds of cults. They introduced us to “cult movements,” “client cults,” and “audience cults.” What unites them, in Bainbridge and Stark’s view, is that they all offer a “compensator,” or some form of reward, for the things invested into the group – whether that’s time, money, or belief. It’s like getting a loyalty card for your spiritual or philosophical endeavors!

Let’s break them down, shall we? A “cult movement” is your fully-fledged, complete organization, but here’s the key: it’s not just a splinter off a bigger, older religion, which is how they differentiate it from a “sect.” Then you’ve got “audience cults,” which are much more loosely organized, often propagated through media, like a self-help guru whose teachings spread via books and talks. And finally, there are “client cults,” which are all about offering services, whether it’s psychic readings, meditation sessions, or even unique therapies.

What’s super interesting is how these types can morph into one another. The Church of Scientology, for instance, is cited as a prime example of a group that transitioned from an audience cult to a client cult. It shows that these social phenomena aren’t static; they’re dynamic, evolving, and constantly adapting. While many academics eventually abandoned the term “cult,” sociologists who follow the Bainbridge-Stark classification actually tend to continue using it. Though, to be fair, Bainbridge himself later admitted he regretted having used the word at all, and even he and Stark began to question the utility of the concept of “conversion,” suggesting “affiliation” as a more fitting term. It’s a reminder that even the experts are constantly refining their language and understanding!

11. **The Academic Shift: “New Religious Movements” Take the Stage**Remember how we talked about the word “cult” shapeshifting? Well, by the 1970s, it had shifted so much, and become so loaded with negative baggage, that the academic world decided enough was enough. Seriously, with the rise of secular anti-cult movements and the dramatic, often tragic, headlines, scholars started to abandon the term “cult” almost entirely. They saw it as inherently pejorative, lacking the neutrality and scientific rigor needed for serious study. It was like finally retiring a trusty, but now broken, old pickup truck because a shiny new model had arrived.

So, what was the replacement? Enter the much more neutral and, frankly, less judgmental, term: “new religion” or, even more commonly, “new religious movement” (NRM). This became the preferred nomenclature in academia, providing a way to discuss these diverse groups without immediately triggering negative connotations. Other proposed alternatives popped up too, like “emergent religion,” “alternative religious movement,” or “marginal religious movement.” But NRM? That’s the one that really stuck.

However, not everyone was thrilled with this linguistic pivot. The anti-cult movement, predictably, wasn’t having any of it. They largely regarded “new religious movement” as a mere euphemism for “cult,” arguing that it sanitized the groups and, crucially, lost the vital implication that many of them were harmful. It highlights a persistent divide between academic objectivity and the deeply personal, often traumatic, experiences that fueled anti-cult activism.

It’s pretty wild to think about, but J. Gordon Melton noted that in 1970, “one could count the number of active researchers on new religions on one’s hands.” Yet, as James R. Lewis observed in 2004, there was a “meteoric growth” in this field of study, largely attributed to the very “cult controversy” of the early 1970s. That “wave of nontraditional religiosity” spurred academics to recognize these groups as distinct phenomena, needing new frameworks – and new words – to understand them. It’s a classic example of how societal shifts can drive academic innovation!

12. **When Governments Step In: Labeling and Religious Freedom Concerns**You know things are serious when governments start weighing in on what to call a religious group. The application of labels like “cult” or “sect” in official government documents really signifies how deeply the popular, negative usage of “cult” (and its functionally similar counterparts like *sekten* in German or *sectes* in French) had permeated public discourse. It’s not just a casual insult anymore; it’s official policy, which carries a whole different kind of weight and consequence.

Unsurprisingly, sociologists who are highly critical of this negative, politicized use of the word argue that it can gravely impact the religious freedoms of group members. Imagine your beloved community suddenly being deemed “dangerous” by the state – that’s a huge deal for personal liberty. At the height of the counter-cult movement and the infamous “ritual abuse scare” of the 1990s, some governments actually went ahead and published official lists of “cults.” It was a time of heightened panic, leading to some truly questionable governmental overreach.

But here’s the rub: these governmental documents, while using similar scary terminology, didn’t necessarily include the same groups. Even worse, their assessments often weren’t based on any agreed-upon criteria. It was a bit of a free-for-all, driven more by public hysteria than by objective analysis. Thankfully, other governments and world bodies took a more measured approach, reporting on new religious movements but *without* using these inflammatory terms. Wisdom, it seems, sometimes prevails!

Interestingly, since the 2000s, there’s been a noticeable shift, with some governments starting to distance themselves from these kinds of blanket classifications of religious movements. They realized that maybe, just maybe, broad-brush labeling wasn’t the best look. However, the official response has been pretty mixed across the globe. While some pulled back, others actually doubled down, aligning more closely with the critics of these groups to the extent of drawing clear lines between “legitimate” religion and what they deemed “dangerous,” “unwanted” cults in public policy. It’s a complex, ever-evolving dance between state control and individual faith.

13. **Global Divide: China, Russia, and the West’s Varied Approaches**So, how do different countries handle groups that fall outside the religious mainstream? The global landscape is a mosaic of varied, and often starkly contrasting, approaches. Let’s start with China, where the government has a long, long history of categorizing certain religions as *xiéjiào* (邪教), which translates rather menacingly to “evil cults” or “heterodox teachings.” This isn’t a new phenomenon; for centuries, this label has been applied.

What’s fascinating about China’s *xiéjiào* classification is that it doesn’t necessarily mean the government believes a religion’s teachings are false or inauthentic. Nope, the label is primarily applied to religious groups that aren’t authorized by the state, or, crucially, those believed to challenge the legitimacy of the state. It’s less about theology and more about political control. And if a group is branded *xiéjiào*? They face severe suppression and punishment from authorities. The most notable example in modern times is undoubtedly Falun Gong, which became the prime target of this classification.

Now, let’s pivot to Russia, where a different but equally stern approach has emerged. In 2008, the Russian Interior Ministry prepared a rather extensive list of “extremist groups.” Topping that list were various Islamic groups that didn’t adhere to “traditional Islam,” which, conveniently, is supervised by the Russian government. Right after those? “Pagan cults.” Talk about a broad sweep!

The Russian government didn’t stop there. In 2009, the Ministry of Justice established a new body, the “Council of Experts Conducting State Religious Studies Expert Analysis.” This council proceeded to list 80 large “sects” that it considered potentially dangerous to Russian society, adding that there were thousands of smaller ones. And get this: the large sects they listed included widely recognized denominations like The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and other groups loosely referred to as “neo-Pentecostals.” It highlights a clear governmental effort to categorize and potentially control religious expression outside a narrowly defined mainstream.

Compare these authoritarian approaches with the mixed bag we’ve seen in Western Europe. As we touched on earlier, countries like France and Belgium, heavily influenced by events like the tragic mass murder/suicides perpetuated by the Solar Temple, adopted policy positions that somewhat uncritically accepted “brainwashing” theories. This led to a more interventionist stance. Yet, other European nations, such as Sweden and Italy, were much more cautious regarding “brainwashing” and consequently responded with a more neutral, less alarmist approach toward new religions. Even within the Roman Catholic Church, clergymen and officials in the 1980s expressed concern that anti-cult laws being considered could adversely affect some orders and groups within their own faith. It just goes to show, there’s no single rulebook when it comes to navigating these complex social groups.

14. **The American Legal Landscape: Free Will, First Amendment, and the Brainwashing Battle**The United States, with its robust constitutional protections, has its own unique story when it comes to the ‘cult’ controversy. In the 1970s, the “brainwashing theory” we discussed earlier became a truly central, even pivotal, topic in US court cases. It was often trotted out by expert witnesses, trying to justify the use of forceful “deprogramming” of individuals who had joined these new religious groups. The idea was that if someone was “brainwashed,” their free will was compromised, justifying extreme interventions.

But hold on a minute! On the other side of the courtroom, sociologists who were deeply critical of these theories actually stepped up. They often assisted advocates of religious freedom, working to defend the legitimacy of new religious movements in court. And here’s why that was so important: in the United States, the religious activities of groups labeled “cults” are very much protected under the First Amendment of the Constitution. That means freedom of religion, speech, and assembly – pretty foundational stuff. However, and this is a big “however,” no members of religious groups or cults are granted any special immunity from criminal prosecution. If you break the law, your religious affiliation won’t save you!

Then came a truly landmark moment: the 1990 court case of *United States v. Fishman*. This ruling effectively put an end to the widespread usage of “brainwashing theories” by expert witnesses like Margaret Singer and Richard Ofshe in American courts. It was a huge shake-up! The court didn’t pull any punches, citing the Frye standard, which dictates that any scientific theory presented by expert witnesses must be *generally accepted* in their respective fields.

The court definitively deemed “brainwashing” to be inadmissible in expert testimonies. They backed this decision with a mountain of evidence, including supporting documents published by the APA Task Force on Deceptive and Indirect Methods of Persuasion and Control, extensive literature from previous court cases where brainwashing theories had been challenged, and compelling expert testimonies delivered by renowned scholars like Dick Anthony. It was a decisive legal and scientific rejection that fundamentally changed how these groups could be discussed in legal settings.

This pivotal court decision solidified a major shift in both legal and academic circles regarding the “brainwashing” narrative. It underscored the importance of distinguishing between genuine coercive control and the often-misunderstood processes of religious conversion or intense group affiliation. The battle over the definition and perceived danger of “cults” continues, of course, but the American legal landscape, grounded in its constitutional freedoms and informed by evolving scholarship, has certainly charted a distinctive course.

Well, that was quite the journey, wasn’t it? From the murky origins of a contentious word to the halls of academia, the pulpits of countercult movements, and the high stakes of global governmental policies, the story of ‘cults’ is anything but simple. It’s a testament to how deeply our understanding of social groups is intertwined with our history, our psychology, and our collective anxieties. These aren’t just obscure footnotes in history; they’re vibrant, often challenging, threads woven into the fabric of human society, constantly reminding us to question, to understand, and to approach with both caution and curiosity. Like those ‘cult-favorite’ small trucks that once defined an era, the ideas and controversies surrounding ‘cults’ have left an indelible mark, shaping how we see the world and our place within its myriad communities. And who knows, maybe one day, the term ‘cult’ itself will undergo another transformation, leaving us to recall its past iterations with a mix of nostalgia and wonder.”

, “_words_section2”: “2000