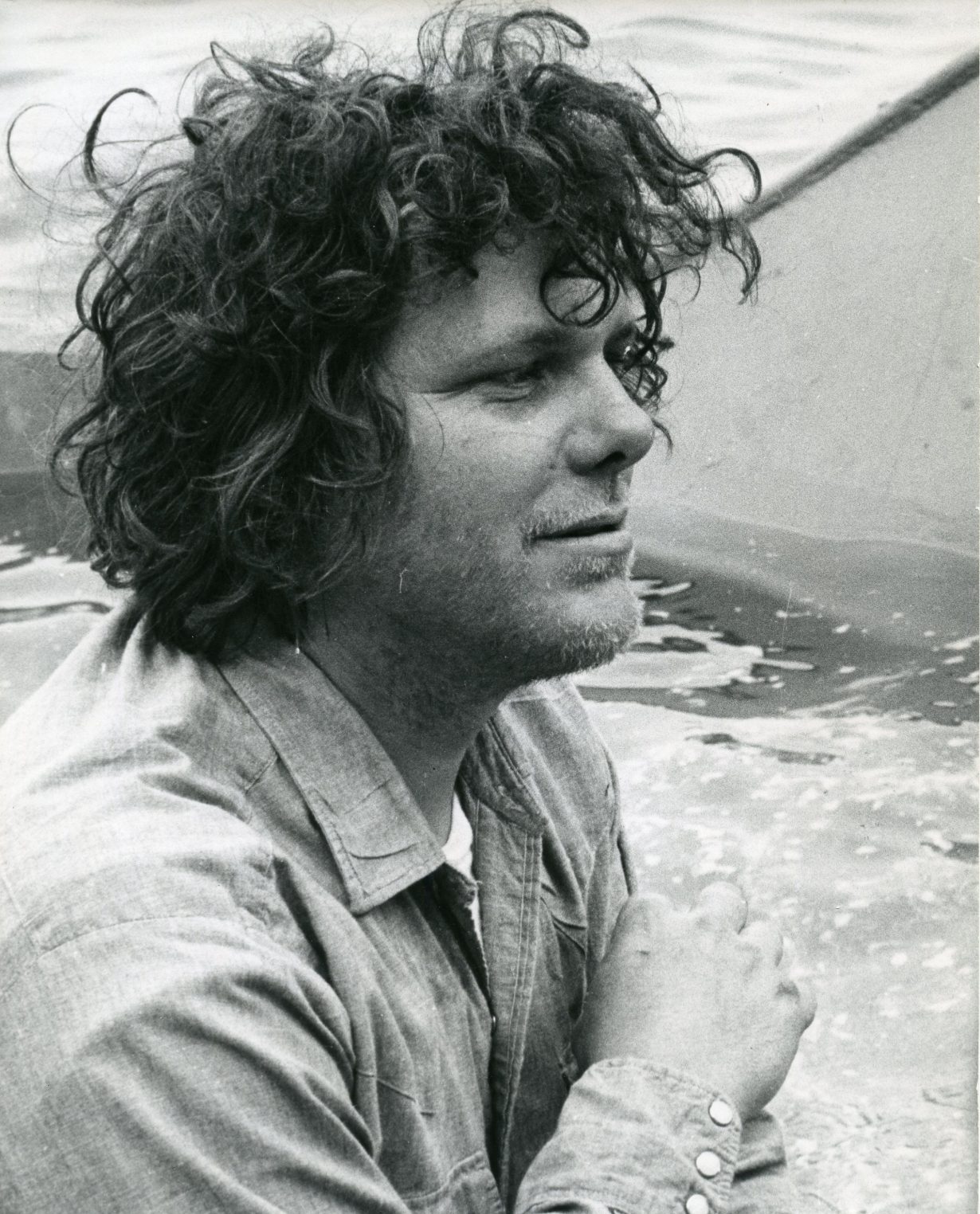

Robert Grosvenor, an artist whose singular vision challenged conventional notions of space, gravity, and artistic classification, died on September 3rd at his home in East Patchogue, N.Y. He was 88. His passing, attributed to kidney cancer, marks the end of a prolific six-decade career during which his enticing and enigmatic art, from monumental sculptures to photographs of peculiar items, continually defied easy categorization. Grosvenor’s work, which centered on the intricate interaction between objects and the often-overlooked spaces they occupied, leaves behind a legacy of profound innovation and a quiet yet persistent questioning of artistic norms.

The news was announced by Paula Cooper Gallery, which had represented the artist from 1968 to 2023, a testament to the enduring relationship between Grosvenor and one of the art world’s significant institutions. Throughout his life, Grosvenor cultivated a practice that, while initially linked to the burgeoning Minimalism movement, swiftly diverged, carving out a unique path characterized by an embrace of rough materials, unexpected forms, and a deep respect for the intrinsic qualities of his chosen mediums. His art, as critic Roberta Smith once eloquently described, revealed him as “the lone wolf of sculpture,” whose career “unfolded in singular surprises.”

A major retrospective of his work, which opened at the Fridericianum in Kassel, Germany, just days before his death, is currently on view through January 2026. This exhibition offers a timely opportunity to reflect on the immense contributions of an artist widely revered by his peers and the generations that followed. This article endeavors to illuminate the extraordinary life and distinctive oeuvre of Robert Grosvenor, exploring the key periods and artistic developments that cemented his status as a true innovator who continuously pushed the boundaries of sculptural practice and perception.

1. **A Life Defined by Art and Intrigue: Early Years and European Studies**Robert Grosvenor was born in New York in 1937, though his upbringing spanned diverse American landscapes, from the arid expanses of Arizona to the coastal charm of Newport, Rhode Island. These contrasting environments, as he noted, were profoundly “formative” to his artistic sensibility, imbuing his work with an awareness of expansive, flat horizons and the subtle nuances of scale. He recalled the sight of diminutive Frank Lloyd Wright houses dotting the arid Southwestern landscape, an early indication of his keen observation skills.

The 1950s marked a pivotal chapter in Grosvenor’s development, as he embarked on a transatlantic journey to Europe to pursue formal art education. He openly shared his motivation for leaving the U.S., stating he “had had enough of boarding schools” in America, seeking a different kind of intellectual and creative awakening. His academic path led him through esteemed institutions such as the École des Beaux Arts in Dijon, France, in 1956; the École Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris from 1957 to 1959; and the Università di Perugia in Italy in 1958.

During this period, Grosvenor received a classical education, which, paradoxically, fueled his inclination towards the avant-garde. He recounted how he was “discouraged from looking at artists like Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni,” whose experimental practices challenged the post-war norms of painting and sculpture. True to his independent spirit, he immediately found himself “attracted to Fontana and Manzoni,” asserting, “I usually don’t go along with what people tell me to do.” This early defiance of conventional wisdom was a precursor to the unclassifiable nature of his mature work.

His time in Paris also immersed him in an expatriate art crowd that included notable literary figures such as William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso, and Allen Ginsberg. This vibrant intellectual and artistic milieu undoubtedly broadened his perspectives, exposing him to diverse forms of creative expression beyond the confines of traditional fine art. Such experiences laid a crucial foundation for an artist who would, for over six decades, consistently resist easy categorization and embrace a multidisciplinary approach encompassing sculpture, photography, drawing, and collage.

2. **Forging Connections: Military Service and the Park Place Co-op**Grosvenor’s European sojourn was interrupted in 1959 when he was called back to the United States for military service. Although he was conscripted, he never saw active combat, recalling instead that he mainly spent his time “marching around New York.” This period, seemingly a departure from his artistic pursuits, proved to be another unexpected catalyst for his career, bringing him into contact with key figures and movements that would shape his artistic trajectory.

While fulfilling his military obligations, he encountered art magazines that featured the work of sculptor Mark di Suvero, whose innovative practice immediately captivated him. This admiration soon transformed into a personal connection. Grosvenor befriended di Suvero, who became a crucial link to the burgeoning downtown New York art scene, a fertile ground for experimentation and radical artistic ideas. It was through di Suvero that he was introduced to a vibrant community of artists and galleries, including the Green Gallery, which provided an early platform for avant-garde figures like Yayoi Kusama, Mark di Suvero himself, and Donald Judd.

These connections were instrumental in opening up the New York art world for Grosvenor, as he himself told Sarah Dziedzic of the Storm King Art Center in 2018. He remarked, “It sort of opened things up for me. It was an important time,” reflecting on the significance of this period for his integration into a dynamic artistic community. He found studio space in the same building as di Suvero, solidifying these crucial early friendships and professional relationships.

By the early 1960s, Grosvenor became an integral part of a maverick group of artists who established their own cooperative gallery in Manhattan’s then-derelict financial district. Named Park Place after its address at 79 Park Place, this artist-run space was housed in what was then a “ghost town,” offering prime real estate for artists to colonize and experiment outside the mainstream art establishment of the Upper East Side. The gallery’s members, including luminaries like di Suvero, Dean Fleming, Tamara Melcher, Forrest Myers, and David Novros, were united by their commitment to making work that challenged prevailing conventions.

At the helm of Park Place was Paula Cooper, a figure who would later become an art world power broker in her own right. Cooper humbly described her role during that period, stating, “I worked for them,” highlighting the collaborative and artist-centric spirit of the cooperative. This initial collaboration between Grosvenor and Cooper marked the beginning of a profound and enduring professional relationship that would span more than fifty years, with her gallery representing him from its opening in 1968 until his death in 2023.

3. **From Canvas to Three Dimensions: The Genesis of a Sculptor**Before establishing his reputation as a sculptor, Robert Grosvenor initially concentrated on painting. However, this phase of his artistic output was, by his own admission, a period of transition and exploration. He later described his early ventures as “paintings that came off the wall,” a phrase that hints at his nascent desire to break free from the two-dimensional plane and engage with space in a more physical, assertive manner. Significantly, he chose not to keep these early works, explaining, “I didn’t feel that confident about them,” a candid reflection of an artist pushing past his own uncertainties.

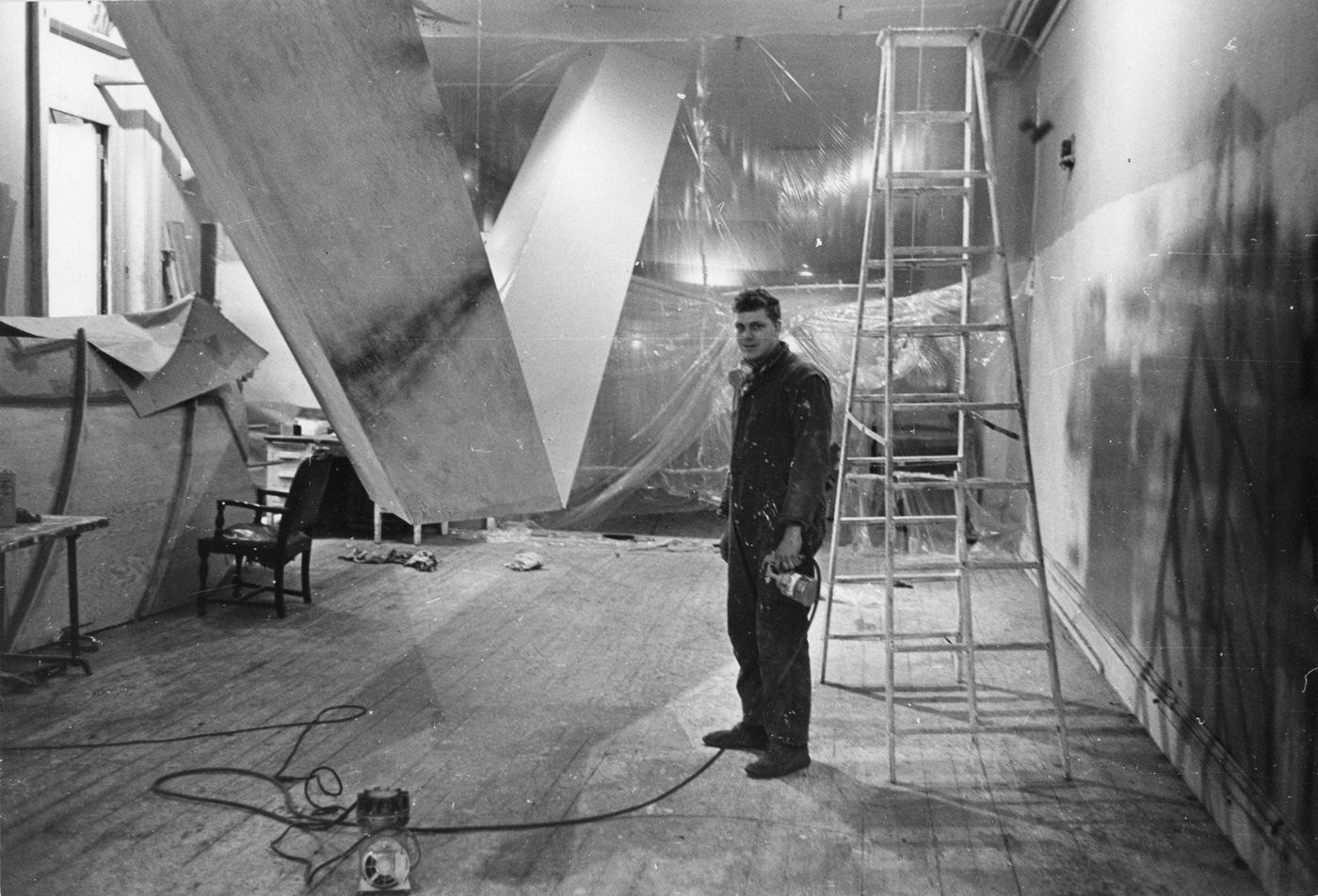

This internal push towards three-dimensionality quickly manifested in his practice. In the early 1960s, Grosvenor began experimenting with materials such as plywood and two-by-fours, taking direct inspiration from architectural forms and engineering principles. Working out of a large Broome Street studio, one floor beneath the renowned James Rosenquist, Grosvenor started to develop the sculptural vocabulary that would define his groundbreaking career. This period marked a crucial pivot, as he fully embraced sculpture as the primary vehicle for his artistic inquiry, moving away from painting to explore mass, volume, and complex spatial dynamics.

His first fully three-dimensional work, a significant milestone in his career, was the 1965 wood and steel piece titled *Topanga*. This sculpture, which appeared to “rise off the floor before coming back down toward it,” embodied his innovative approach to form and gravity. Its construction, utilizing industrial materials like wood and steel, foreshadowed his later engagement with rougher, found objects, but already showcased his knack for creating visually arresting structures that challenged perceptual expectations.

It was *Topanga* that Grosvenor chose to show at Park Place, the New York cooperative directed by Paula Cooper, signaling his confidence in this new direction and marking his public emergence as a sculptor of distinctive vision. The successful reception of this work at such a pivotal gallery solidified his commitment to sculpture and provided him with the validation to further explore the uncharted territories of his artistic imagination. The piece demonstrated an early sophistication in balancing visual lightness with actual physical presence.

4. **Challenging Gravity: The Iconic Cantilevered Sculptures**The mid-1960s proved to be a seminal period for Robert Grosvenor, as he unveiled a series of groundbreaking cantilevered sculptures that would establish his reputation and become synonymous with his early work. These monumental pieces dramatically engaged with architectural space, often appearing to float or defy the laws of physics, thereby captivating audiences and critics alike. His practice centered on “the interaction between objects and the spaces they occupied,” and these sculptures, with their suspended or cantilevered forms, inherently “called attention to the space around them as much as the structures themselves,” making the surrounding void an active component of the artwork.

One of his earliest and most significant works from this period was *Topanga* (1965), which he exhibited at Park Place. This giant structure, constructed from plywood and Masonite and painted in striking silver and bright yellow, was shaped distinctly, resembling “the first two strokes of the letter N, with the upstroke planted on the floor and the down stroke’s point hovering, ever so slightly, above the floor.” The inspiration for this piece was as intriguing as the sculpture itself: a photograph Grosvenor had seen of a 110-foot-high solar telescope in Arizona, demonstrating his ability to translate real-world observations into abstract, powerful forms that retained a sense of underlying wonder.

Following *Topanga*, Grosvenor continued to push the boundaries of his sculptural ambition. In 1966, he presented *Transoxiana* (1965) in the landmark exhibition “Primary Structures” at New York’s Jewish Museum. This V-shaped wood-and-steel sculpture, a “31-foot angular cantilevered sculpture,” played a crucial role in defining Minimalism by showcasing how industrial materials could be used to create stark, geometric forms with immense presence. *Transoxiana* created a dynamic visual effect by “coming down from the ceiling before rising back up,” further solidifying Grosvenor’s mastery of suspended forms and his unique ability to manipulate perceptions of weight and stability.

Two years later, Grosvenor’s cantilevered sculptures were introduced to European audiences in the “Minimal Art” exhibition at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag in the Netherlands. For this show, he presented an even larger-scale untitled cantilevered sculpture from 1968–70. This steel work, painted white, was “suspended from the ceiling, where it hovered over the heads of viewers,” creating an immersive and somewhat disorienting experience, forcing the audience to look up and engage with the overhead space. The audacity of these suspended works, defying expectation and traditional pedestals, was an absolute standout.

This particular work, *Untitled* (1968–70), was later memorably recreated by Grosvenor for the Institute of Contemporary Art Miami in 2018, underscoring its enduring significance and his continued engagement with these foundational concepts throughout his career. These early cantilevered sculptures were not merely formal exercises; they were conceptual statements that questioned the very ground beneath the viewer’s feet, inviting a reevaluation of gravity, balance, and the often-unseen forces at play in constructed environments. They defined a period of audacious sculptural innovation.

5. **The Minimalist Embrace and Subsequent Departure**Robert Grosvenor emerged onto the New York art scene during the 1960s, a period when Minimalism was gaining significant traction. His early works naturally aligned him with this influential movement. His participation in seminal exhibitions like “Primary Structures” at the Jewish Museum in 1966, alongside pioneers such as Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt, and “Minimal Art” at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag in 1968, cemented his initial association with Minimalism. These early pieces, characterized by their geometric forms, industrial materials, and spare aesthetics, resonated with the movement’s core tenets of reductive forms and an emphasis on objecthood.

However, Grosvenor’s artistic spirit was too independent to remain confined within any single stylistic box. While he “gained acclaim in New York during the 1960s when he showed his work alongside famed Minimalists,” he swiftly began to diverge from its strict formalism and sleek abstract aesthetics. Critics and admirers soon recognized a fundamental difference in his approach, even as his works continued to be “spare and made from industrial materials.” His methods subtly but surely pulled him away from the minimalist orthodoxy, hinting at a more idiosyncratic vision.

As Roberta Smith of The New York Times aptly observed, “In the late 1960s he was almost a Minimalist, but was disqualified by a growing penchant for working with rough materials, scrappy found objects and his own hands.” This hands-on, often unrefined approach, coupled with his willingness to embrace imperfection and the raw qualities of his chosen mediums, set him apart from the smooth, often factory-fabricated surfaces favored by many Minimalists. His process was less about industrial precision and more about direct engagement with material.

His subsequent works became increasingly “idiosyncratic,” flirting with Minimalist aesthetics only to “strike out on his own and create pieces that were totally unclassifiable.” This distinctiveness earned him the moniker of “the lone wolf of sculpture” from Smith, a title that perfectly encapsulated his refusal to conform. Grosvenor’s practice prioritized an exploration of the spatial relationship between the viewer, the work, and its surrounds, often with a “dry wit and opaqueness that, at times, perplexed his audience,” moving beyond Minimalism’s focus on pure objecthood and seriality towards something more ambiguous and experiential.

This deliberate departure from a singular movement was not a rejection of Minimalism’s principles but an expansion upon them, infused with his unique sensibility. He demonstrated that art could be “tough to place within any movement,” maintaining a connection to industrial materials and geometric structures while introducing elements of narrative, raw materiality, and an almost mischievous sense of mystery. This independent trajectory, marked by “singular surprises” and a consistent resistance to easy categorization, became one of the defining characteristics of Grosvenor’s long and impactful career.

6. **Transforming the Mundane: The Found Objects of the 1970s**The 1970s marked a significant shift in Robert Grosvenor’s artistic practice, as he began to integrate found materials, transforming ordinary, often discarded, objects into profound sculptural statements. This evolution moved him further away from the sleek, fabricated forms associated with early Minimalism and into a more tactile, raw, and earthy aesthetic. His choice of materials during this decade was bold and unconventional, reflecting a growing interest in the inherent qualities and histories embedded within everyday detritus, challenging the notion of what constitutes artistic medium.

A prominent example of this new direction was his work with discarded wooden telephone poles. Grosvenor would take these heavy, industrial remnants and subject them to processes that some critics described as “violent,” sawing and breaking them apart. The resulting forms were far from pristine; they were instead imbued with a rugged authenticity, a testament to the passage of time and the forces of both nature and human intervention. Critic Joseph Masheck, writing in Artforum, observed this transformation, stating, “What is left is beautiful, but not because anything has been added, and not because any preexisting but hidden beauty has been revealed.” Rather, the beauty emerged from the raw act of intervention and the presentation of the material itself.

To these fragmented wooden beams, Grosvenor applied creosote, a “fragrant chemical” that is also “toxic and pungent,” typically used to strengthen rail ties. This application lent the sculptures a dark, almost ominous appearance, creating a “greasily ominous look,” especially when he later experimented with motor oil. The creosote not only altered the visual and tactile qualities of the wood but also introduced a potent olfactory dimension to his work, engaging viewers on multiple sensory levels and evoking associations with industry, decay, and preservation. The material’s inherent properties became an integral part of the aesthetic experience.

These sculptures, often resting horizontally on the ground with “symmetrical fractures,” presented a stark contrast to his earlier gravity-defying cantilevered pieces. They invited a different kind of contemplation, focusing on the weight, texture, and natural imperfections of the found objects, anchoring the viewer to the earth rather than inviting them to look upwards. The choice to place these heavy, altered beams directly on the floor emphasized their raw materiality and the deliberate manipulation of their original function, forcing a re-evaluation of their identity.

This period showcased Grosvenor’s fearless experimentation and his capacity to find artistic resonance in the most unexpected materials, further solidifying his reputation as an artist who continually defied expectations and expanded the very definition of sculpture. The transformation of the mundane into the meditative became a hallmark of his sustained artistic innovation, signaling a profound shift towards a more object-oriented and materially focused practice.