In the annals of Hollywood, few figures loom as large and as enigmatically as Robert Mitchum. With a screen presence that was simultaneously laconic and intensely compelling, he carved out a niche as the quintessential antihero, his weary eyes and deep, resonant voice becoming synonymous with the shadowy, morally ambiguous world of film noir. He wasn’t just an actor; he was a force of nature, a legend who seemed to embody the very soul of a genre, earning commendation from critics like Roger Ebert, who famously called him his favorite movie star and the true essence of film noir.

His career, spanning decades, was marked by an astonishing range and a consistent ability to imbue even the most complex characters with a profound sense of lived experience. Mitchum’s enduring appeal lay in his authenticity, a quality forged in a life rich with unconventional experiences long before he ever stepped onto a soundstage. It was a journey from a restless youth to celebrated stardom, marked by both personal struggles and unparalleled cinematic triumphs.

Indeed, as David Thomson once observed, “Since the war, no American actor has made more first-class films, in so many different moods.” This article endeavors to trace that extraordinary trajectory, exploring the pivotal moments, iconic roles, and personal narratives that shaped Robert Charles Durman Mitchum into an unforgettable Hollywood icon, whose legacy continues to captivate and inspire audiences worldwide.

1. **A Rugged Genesis: Robert Mitchum’s Formative Years and Early Wanderlust**Born on August 6, 1917, in Bridgeport, Connecticut, Robert Charles Durman Mitchum’s early life was anything but conventional, setting a foundational tone for the rugged independence that would define his screen persona. His background was a rich tapestry of Scots-Irish, Native American, and Norwegian descent, a heritage that perhaps contributed to his distinctive, sometimes inscrutable, demeanor. Tragedy struck early when his father, a shipyard and railroad worker, was crushed to death in a railyard accident in Charleston, South Carolina, in February 1919, leaving his mother, Ann Harriet Gunderson, a pregnant widow awarded a government pension.

His mother, a Norwegian immigrant and sea captain’s daughter, eventually remarried to Lieutenant Hugh “The Major” Cunningham Morris and found employment as a linotype operator for the Bridgeport Post, after her children were old enough for school. Despite these attempts at stability, young Mitchum was a restless spirit, quickly earning a reputation as a prankster frequently involved in fistfights and mischief. This rebellious streak led to his expulsion from Felton High School in Delaware, where he had been sent to live with his grandparents.

The urge for independence led Mitchum to leave home for the first time at the tender age of 11. By 14, he had fully embarked on a life of itinerant wandering, traversing the country by hopping freight cars and taking on a bewildering array of odd jobs, from ditch digging and fruit picking to dishwashing. This early exposure to the harsh realities of life on the road undoubtedly instilled in him a world-weariness and self-reliance that would later become hallmarks of his acting style. It was during this period, in the summer of 1933, that a significant incident occurred: he was arrested for vagrancy in Savannah, Georgia, and briefly placed on a local chain gang. By his own account, he managed to escape, hitchhiking his way back to Rising Sun, Delaware, where his family had since moved.

During his recovery from injuries that nearly cost him a leg in the fall of 1933, a pivotal meeting took place. At just 16 years old, he encountered 14-year-old Dorothy Spence, the young woman who would eventually become his wife and lifelong companion. Following a brief stint with the Civilian Conservation Corps, digging ditches and planting trees, Mitchum’s wanderlust resurfaced. He headed to Long Beach, California, where his older sister, Julie, had settled, continuing his cross-country travels and various jobs for three more years, even participating in 27 professional boxing matches before retiring from the ring after an injury.

2. **The Fledgling Actor: First Forays into Hollywood and the War Effort**By 1937, the nomadic existence had somewhat subsided, and Mitchum had settled into a more rooted life in Long Beach, California. His older sister, Julie, an aspiring performer, became a member of a local theater group called the Players Guild. Initially, Robert merely accompanied her to rehearsals, but soon, the vibrant world of stage productions piqued his interest. Encouraged by his mother and sister, he joined the Players Guild himself, making his stage debut in August 1937, an early indicator of the artistic inclinations that lay beneath his rough-hewn exterior.

His involvement with the Players Guild deepened, as he continued to appear in their productions and even penned two children’s plays. When Julie ventured into cabaret singing, Mitchum showcased another facet of his creative talent, writing lyrics for her and other performers. A notable early achievement came in 1939, when he wrote and composed an oratorio that was presented at a Jewish-refugee-benefit show, an event notably produced and directed by the legendary Orson Welles, marking a fascinating, albeit early, connection to a cinematic titan.

His personal life saw a significant development in 1940 when he returned to Delaware to marry Dorothy Spence, bringing her back to California. The demands of a growing family, especially with his wife’s pregnancy, prompted Mitchum to seek a more stable income. During World War II, he took a demanding job as a sheet metal worker at the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. However, the cacophony of the machinery at Lockheed severely damaged his hearing, and the graveyard shift led to chronic insomnia and temporary blindness, symptoms his doctors attributed to job-related anxieties. This ordeal ultimately led him to leave Lockheed.

With his health compromised but his resolve undeterred, Mitchum turned his gaze towards the burgeoning film industry. An agent he knew from his theater days helped secure him an interview with Harry Sherman, the producer behind United Artists’ popular Hopalong Cassidy Western film series. In June 1942, Mitchum officially began his film career, taking on a minor villainous role in “Border Patrol.” This marked the first of seven Hopalong Cassidy films he would make, all released in 1943. That year proved remarkably prolific, with Mitchum appearing in a total of 19 films, including his first non-Western, “Follow the Band,” and an uncredited part as a soldier in MGM’s major picture, “The Human Comedy.” Despite receiving an offer for a studio contract from Harry Cohn after his performance in Columbia’s musical “Doughboys in Ireland,” Mitchum, ever the independent spirit, declined.

3. **Breakthrough on the Battlefield: *The Story of G.I. Joe* and Critical Acclaim**While his early filmography was extensive, primarily comprising supporting roles in B-movies and Westerns, Robert Mitchum’s career trajectory began to pivot dramatically in 1944. His first truly important role came in “When Strangers Marry,” a thriller directed by William Castle for Monogram. In this film, he portrayed a salesman assisting his former girlfriend in unraveling a murder mystery, opposite seasoned actors like Dean Jagger and Kim Hunter. His performance garnered positive reviews, and the film itself is now regarded as a standout example of B-movie cinema, showcasing his nascent but undeniable talent.

That same year, his potential was further recognized with a small but impactful role in the war film “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo,” which starred Van Johnson and Robert Walker, with Spencer Tracy in a guest performance. Director Mervyn LeRoy was particularly impressed by Mitchum’s raw talent and subsequently recommended him to RKO. This recommendation proved instrumental, as on May 25, 1944, Mitchum signed a significant seven-year contract with RKO, commencing at a weekly salary of $350. His first RKO film was the comedy “Girl Rush,” and he was soon groomed for B-Western stardom in two Zane Grey adaptations, “Nevada” and “West of the Pecos,” with “Nevada” marking his first instance of receiving star billing. Both films performed well at the box office and earned positive critical reception.

The true watershed moment arrived when RKO loaned Mitchum to independent producer Lester Cowan for a prominent supporting role in “The Story of G.I. Joe” (1945), directed by William A. Wellman. Here, Mitchum delivered a performance that would resonate deeply, portraying a war-weary officer based on Captain Henry T. Waskow, a man who maintained his resolve despite immense challenges. The film, which vividly depicted the life of an ordinary soldier through the eyes of journalist Ernie Pyle (played by Burgess Meredith), was an immediate critical and commercial sensation. General Dwight D. Eisenhower himself lauded it as “the greatest war picture he had ever seen.”

Remarkably, before the film’s release, Mitchum was drafted into the United States Army, serving as a medic at Fort MacArthur, California. “The Story of G.I. Joe” went on to receive four Academy Award nominations, including Mitchum’s sole nomination for Best Supporting Actor. This role firmly established him as a rising star, with Andrew Sarris, nearly three decades later, describing his performance as “extraordinarily haunting” in The Village Voice. Following this success, in 1946, he appeared in “Till the End of Time,” a box office hit about returning Marine veterans, before making a definitive shift towards the genre that would ultimately define his iconic screen persona: film noir.

4. **Defining the Darkness: Mitchum’s Ascent as a Film Noir Icon**It was in the shadowy, morally complex world of film noir that Robert Mitchum truly found his métier, becoming the genre’s enduring face and soul. His natural charisma, combined with an inherent air of fatalism and understated menace, perfectly suited the post-war anxieties and cynical narratives that characterized noir. In 1946, he was cast as the second lead in two significant noir films: Vincente Minnelli’s “Undercurrent” at MGM, where he costarred with Katharine Hepburn and Robert Taylor, playing a troubled man entangled in family affairs; and John Brahm’s “The Locket” at RKO, portraying a bitter ex-boyfriend to Laraine Day’s femme fatale. The latter, renowned for its intricate multi-layered flashbacks, has since achieved cult classic status, hinting at the depth Mitchum could bring to complex characterizations.

1947 marked a crucial turning point, cementing his burgeoning noir star status. He was loaned to Warner Bros. for Raoul Walsh’s “Pursued,” costarring Teresa Wright. In this film, he played a character grappling with a suppressed past and seeking those responsible for his family’s demise, a role that positioned the film as the first noir Western in American cinema and his first high-budget Western. Later that year, Edward Dmytryk’s “Crossfire” featured Mitchum as a World War II soldier embroiled in a murder investigation sparked by an anti-Semite within his ranks. Despite a modest budget, “Crossfire” became RKO’s most profitable film of 1947 and garnered five Academy Award nominations, underscoring Mitchum’s growing commercial and critical appeal. However, his loan-out to MGM for “Desire Me,” costarring Greer Garson, proved a troubled production and a box office disaster, famously being cited as the first major Hollywood film released without a credited director.

Following the successes of “Pursued” and “Crossfire,” Mitchum’s value to the studios became undeniable. He signed a new seven-year contract with RKO and David O. Selznick, immediately seeing his weekly salary leap from $1,500 to $3,000. He concluded 1947 with what would become his signature role in a major RKO production: “Out of the Past” (also known as “Build My Gallows High”). Directed by Jacques Tourneur and costarring Jane Greer and Kirk Douglas, with cinematography by Nicholas Musuraca, the film cast Mitchum as Jeff Bailey, a small-town gas-station owner and former private investigator whose past entanglements with a gambler and a seductive femme fatale resurface to haunt him. RKO executives, initially unimpressed with the finished product, were surprised by its moderate box office success.

Mitchum’s portrayal in “Out of the Past” received widespread praise, with Bosley Crowther of The New York Times finding him “magnificently cheeky and self-assured.” This critical reception firmly established him as a leading man at RKO. Today, “Out of the Past” is universally celebrated as one of the greatest film noirs ever made, with Mitchum’s performance recognized as the definitive embodiment of the genre’s fatalistic anti-hero. His quiet intensity, combined with a weary cynicism, perfectly captured the essence of men caught in circumstances beyond their control, forever linking his image to the dark allure of noir cinema.

5. **Scandal and Steadfastness: The Marijuana Arrest and Its Aftermath**The trajectory of Robert Mitchum’s rapidly ascending career faced an unexpected and dramatic challenge on September 1, 1948, when he was arrested for possession of marijuana alongside actress Lila Leeds. This incident, occurring at the height of his burgeoning stardom, could have easily derailed a lesser actor’s career, but Mitchum’s unique appeal and the studio’s shrewd handling of the situation ultimately saw him emerge with his popularity surprisingly undiminished.

Despite the existence of a morals clause in his contract, RKO made the crucial decision to stand by their star, opting not to cancel his agreement. This act of studio loyalty proved instrumental. Mitchum subsequently served a 50-day sentence, split between the Los Angeles County Jail and a Castaic, California, prison farm, before being released on March 30, 1949. The sensational nature of the arrest was amplified when “Life” photographers were permitted to capture images of him mopping in his prison uniform, providing the public with a stark, yet oddly compelling, glimpse into his predicament. Ever the sardonic wit, Mitchum famously quipped to reporters that jail was “like Palm Springs, but without the riff-raff,” a remark that further cemented his anti-establishment, devil-may-care persona.

In a turn of events that further solidified his resilient image, Mitchum’s conviction was ultimately overturned on January 31, 1951, by the Los Angeles court and district attorney’s office, after it was revealed to have been a setup. This vindication, coupled with the public’s fascination, meant that far from harming his popularity, the scandal arguably enhanced it. RKO, recognizing the opportunity presented by the widespread publicity, shrewdly rushed the release of his upcoming film, “Rachel and the Stranger.” This strategic move paid off handsomely, as the film, costarring Loretta Young and William Holden, became one of RKO’s top-grossing pictures of 1948, proving that Mitchum’s appeal transcended legal woes.

Continuing his prolific output, Mitchum starred in “Blood on the Moon” (1948), a noir Western directed by Robert Wise, where his portrayal of a quiet yet menacing drifter garnered rave reviews, further enhancing the film’s quality. The following year, 1949, saw him in three diverse films: “The Red Pony,” his first color film and a loan-out to Republic Pictures; a reunion with Jane Greer in the successful film noir “The Big Steal”; and a role against type in the romantic comedy “Holiday Affair” opposite Janet Leigh. Although “Holiday Affair” initially struggled at the box office, it has since achieved classic status, enjoying annual television showings. By the close of the 1940s, Robert Mitchum had undeniably become RKO’s biggest star, a fact underscored by Howard Hughes’s acquisition of Selznick’s share of his contract for a substantial $400,000 before the filming of “Holiday Affair.”

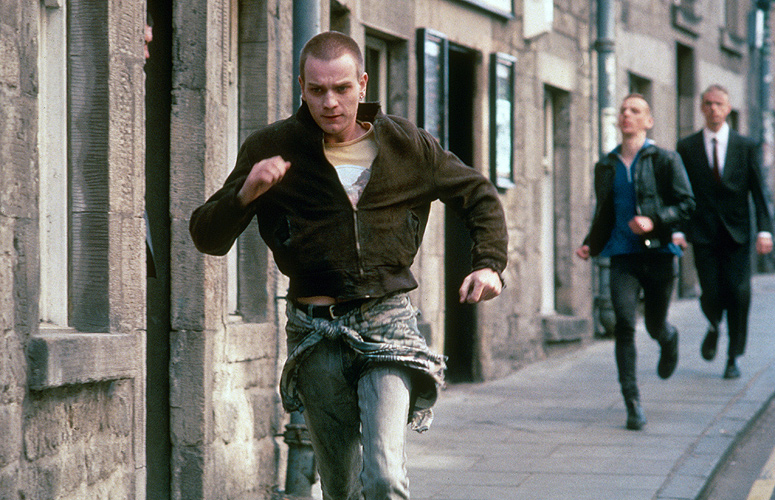

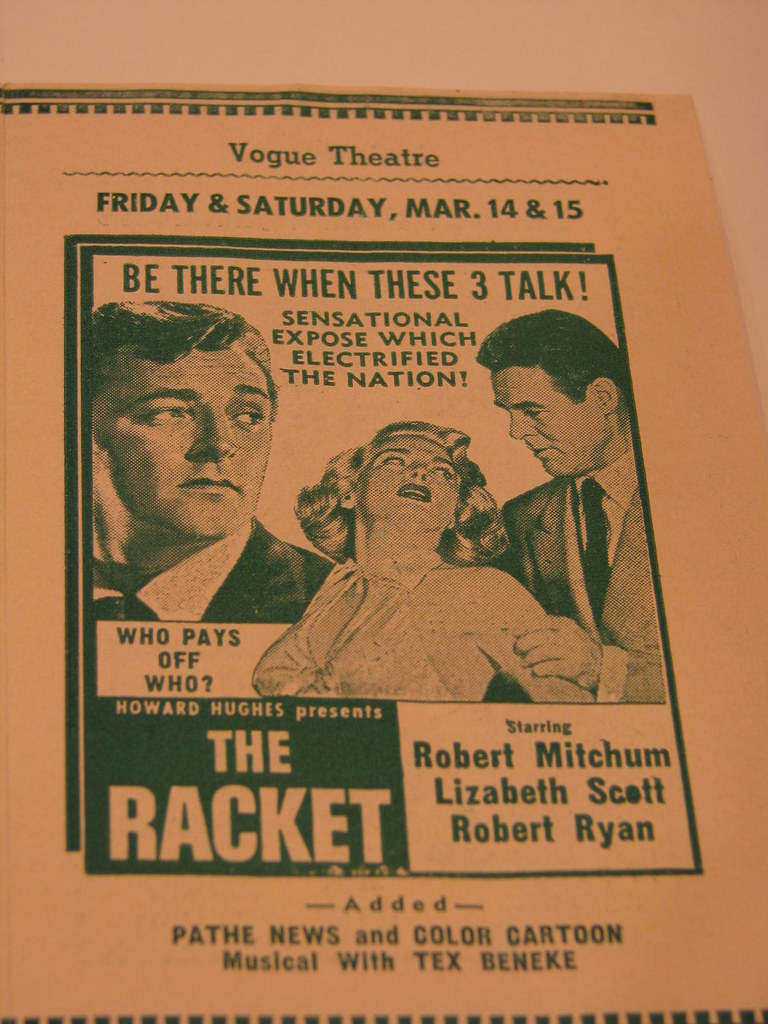

6. **Solidifying Stardom: The 1950s Era of Versatility and Iconic Roles**The dawn of the 1950s saw Robert Mitchum continue his prolific output, particularly in the film noir genre, even as he began to explore an increasingly diverse range of roles. Early in the decade, he starred in a string of noirs, including “Where Danger Lives” (1950), in which he played a doctor embroiled with a mentally unbalanced woman, and “My Forbidden Past” (1951) with Ava Gardner, a film he openly criticized for its disappointing script. Several of these productions, such as “His Kind of Woman” (1951), “The Racket” (1951), and “Macao” (1952), were plagued by extensive reshoots and multiple directors, often at the behest of Howard Hughes. Despite the behind-the-scenes turmoil, some, like “The Racket,” emerged as commercial successes for RKO, further cementing Mitchum’s box office draw.

Beyond noir, Mitchum demonstrated his versatility in other genres. He starred in the Korean War drama “One Minute to Zero” (1952) with Ann Blyth, one of RKO’s major pictures of the year, before making a lauded return to the Western genre in “The Lusty Men” (1952). Directed by Nicholas Ray, his performance as a veteran rodeo champion alongside Susan Hayward and Arthur Kennedy was universally praised by critics. “Variety” and “The Hollywood Reporter” hailed it as his best to date, and Manny Farber, writing in “The Nation,” famously noted, “Mitchum is the most convincing cowboy I’ve seen in horse opry, meeting every situation with the lonely, distant calm of a master cliché-dodger.”

1953 brought “Angel Face,” the first of his three collaborations with Jean Simmons, directed by Otto Preminger. In this dark psychological thriller, Mitchum played an ambulance driver fatally ensnared by a murderously insane heiress. While initial reviews were mixed, “Angel Face” is now celebrated as a noir classic, with Jean-Luc Godard famously listing it among the ten best American sound pictures. Richard Brody, in a retrospective “New Yorker” review in 2010, aptly observed that “the ever-cool Mitchum radiates heat without warmth,” capturing the unique allure he brought to such complex characters. He also ventured into African adventure in “White Witch Doctor” (1953) with Susan Hayward and starred in RKO’s first 3-D production, “Second Chance” (1953), a box office success despite his growing dissatisfaction with RKO’s scripts.

His departure from RKO arrived on August 15, 1954, after starring in the romantic comedy “She Couldn’t Say No” (1954) and a loan-out for Otto Preminger’s Western “River of No Return” (1954) with Marilyn Monroe, a significant box office hit. As a freelancer, 1955 proved to be another pivotal year. He starred in Stanley Kramer’s melodrama “Not as a Stranger,” which became one of the year’s highest-grossing films. However, it was his second film of 1955, Charles Laughton’s sole directorial effort, “The Night of the Hunter,” that would etch his image permanently into cinematic history. Though a commercial failure upon release, this noir thriller, featuring Mitchum as the terrifying, serial-killer preacher Harry Powell, is now widely considered one of the greatest films of all time. His performance, with the iconic “HATE” and “LOVE” tattooed on his knuckles, is regarded as one of the best of his career, a chilling embodiment of primal evil that Dave Kehr described as “the role that most fully exploits his ferocious sexuality.” After a reported firing from “Blood Alley” (1955) where John Wayne took over his role, Mitchum formed DRM Productions in 1955, signing a five-film deal with United Artists, signaling his continued ambition and control over his remarkable career.

Read more about: From Child Stars to Screen Legends: 14 A-Listers and Icons Who Seemingly Vanished from the Spotlight

7. **The Unconventional Sixties: Blending Artistry with Maverick Choices**The vibrant spirit of the 1960s found Robert Mitchum, ever the iconoclast, settling into a different rhythm. After a prolific run in the 1950s, he relocated his family to a farm in Talbot County, Maryland, developing a new passion for quarter horse breeding. This period coincided with a reported indifference to selecting his films, and a declared loss of interest in his work as a producer, leading him to rename DRM Productions as Talbot Productions, merely a “co-production” company. His unpretentious approach to his craft was perhaps best encapsulated when he famously turned down John Huston’s “The Misfits” (1961), citing a dislike for the script and Huston’s demanding nature, opting instead for the service comedy “The Last Time I Saw Archie” (1961), which he would affectionately call his favorite for the generous compensation and time off it afforded him.

Yet, even amidst this shift, Mitchum delivered performances that would cement his reputation for embodying cold, predatory characters. In 1962, he costarred with Gregory Peck in “Cape Fear,” a film that showcased his “cheekiest, wickedest arrogance and the most relentless aura of sadism that he has ever managed to generate,” as Bosley Crowther of The New York Times observed, despite the film itself receiving mixed reviews. That same year, he joined an international ensemble in the epic war film “The Longest Day,” portraying General Norman Cota, a role that garnered critical acclaim for his portrayal of a leader rallying demoralized troops during the D-Day landings, further showcasing his versatility in a commercial and critical success.

However, the middle of the decade saw a string of films that received mostly negative reviews, with Mitchum often perceived as miscast or lethargic. Films like Robert Wise’s romantic drama “Two for the Seesaw” (1962), Huston’s “The List of Adrian Messenger” (1963) where he had a cameo, the adventure film “Rampage” (1963), and Guy Hamilton’s courtroom drama “Man in the Middle” (1964) were met with lukewarm reception, described as either absurd, dull, or disjointed. Even the commercially successful comedy “What a Way to Go!” (1964) was found to be overlong by critics. Despite these cinematic detours, Mitchum’s commitment extended beyond the screen; during this period, he embarked on two USO tours to Vietnam, demonstrating a quiet patriotism.

A return to form arrived in 1965 with “Mister Moses,” where he played a diamond smuggler mistaken for a modern-day Moses, a role that earned him fairly positive reviews for his “casual charm.” His promotional efforts for the film were extensive, a rarity for the typically publicity-averse actor. Then, in 1967, he delivered another iconic Western performance in “El Dorado,” starring alongside John Wayne. Despite initial doubts surrounding the production, the film became a major box office hit, hailed by The Hollywood Reporter as director Howard Hawks’s best work since “Rio Bravo.” Howard Thompson of The New York Times lauded Mitchum’s performance as “simply wonderful,” with Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times noting his portrayal of “one of the loveliest hangover sequences on record.”

Yet, the close of the 1960s brought another mixed bag of critical reception for Mitchum’s six subsequent films. “Villa Rides” (1968) and “Anzio” (1968) suffered from weak scripts and uninspired direction, while “5 Card Stud” (1968), which saw him as a homicidal preacher, was deemed formulaic despite favorable reviews for his performance. Joseph Losey’s “Secret Ceremony” (1968) polarized critics, and the Westerns “Young Billy Young” (1969) and “The Good Guys and the Bad Guys” (1969) received cold or mixed receptions. Notably, Mitchum famously turned down the opportunity to appear in Sam Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch” (1969), expressing a reluctance to work with the director, a testament to his fiercely independent nature and a telling glimpse into his decision-making process during this eclectic decade.

8. **The Transformative Seventies: Evolving Roles and Noir Revivals**As the cinematic landscape shifted into the 1970s, Robert Mitchum continued to defy easy categorization, embracing roles that showcased a different facet of his profound talent. A significant departure from his established tough-guy persona came in David Lean’s 1970 epic, “Ryan’s Daughter.” Here, Mitchum portrayed Charles Shaughnessy, a mild-mannered schoolmaster in World War I–era Ireland. Initially hesitant to take on the demanding schedule and even contemplating retirement, he ultimately accepted after screenwriter Robert Bolt’s persistence. Though the film garnered four Academy Award nominations, and Mitchum himself was widely considered a contender for Best Actor, he famously rejected projects like “Patton” and “Dirty Harry” due to disagreements with their moral scripts, further illustrating his selective approach to his craft.

The decade saw Mitchum make a compelling return to the crime drama genre, albeit with mixed critical results. In 1973, he delivered a memorable performance in “The Friends of Eddie Coyle,” where he embodied an aging Boston hoodlum caught in the treacherous crosscurrents between the Feds and his criminal associates. This nuanced portrayal allowed him to delve into the weariness and moral ambiguities inherent in such a character, a thematic thread that echoed some of his best noir work.

Sydney Pollack’s 1974 film “The Yakuza” offered another intriguing entry, effectively transplanting the classic film noir story arc to the exotic and brutal Japanese underworld. Mitchum’s commanding presence lent itself perfectly to this cultural transposition, demonstrating his ability to anchor complex narratives in unfamiliar settings. His enduring appeal in the genre was further solidified when he took on the iconic role of Philip Marlowe, Raymond Chandler’s quintessential private investigator.

His portrayal of Marlowe in “Farewell, My Lovely” (1975), a remake of the 1944 classic “Murder, My Sweet,” was met with widespread acclaim from both audiences and critics, a testament to his ability to capture the world-weary cynicism and moral fortitude of the character. This success led him to reprise the role in the 1978 remake of “The Big Sleep.” Additionally, Mitchum made an appearance in the 1976 World War II naval battle film “Midway,” showcasing his continued willingness to engage with diverse historical narratives, rounding out a decade that solidified his enduring versatility.

9. **Television Triumphs: From Miniseries Epic to Small-Screen Icon**The 1980s marked a significant expansion of Robert Mitchum’s career into the burgeoning realm of television, where he achieved some of his most widely recognized successes, reaching an audience perhaps even broader than his celebrated film career had garnered. His early foray into the medium included the 1982 film adaptation of Jason Miller’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, “That Championship Season,” where he played Coach Delaney, bringing his signature gravitas to the small screen.

However, it was his starring role in the 1983 miniseries “The Winds of War,” based on Herman Wouk’s epic novel, that cemented his status as a television icon. As U.S. Navy Captain Victor “Pug” Henry, Mitchum anchored the sprawling, big-budget production, which meticulously examined the events leading up to America’s involvement in World War II. The miniseries was a monumental success, watched by an astounding 140 million people over seven days, making it the most-watched miniseries up to that point and extending his reach into millions of American households.

He reprised his iconic role as “Pug” Henry in the 1988 sequel miniseries, “War and Remembrance,” which continued the sweeping narrative through the conclusion of the war, further solidifying his legacy in long-form television storytelling. In 1985, he also appeared in another significant miniseries, “North and South,” playing George Hazard’s father-in-law, an important contribution to a genre that captivated national audiences. His continued engagement with the medium showcased an adaptability that few stars of his generation possessed.

Beyond these dramatic triumphs, Mitchum even brought his unique charm to comedy. In 1987, he famously guest-hosted “Saturday Night Live,” where he offered a final, parody performance of Philip Marlowe in a sketch titled “Death Be Not Deadly.” The show also featured a short comedy film he made, “Out of Gas,” a mock sequel to “Out of the Past,” written and directed by his daughter, Petrine, with Jane Greer reprising her original role. He also appeared in the 1986 made-for-TV movie “Thompson’s Run” and the 1988 Richard Donner comedy “Scrooged,” illustrating his willingness to embrace a variety of projects in his later career.

10. **Personal Battles and Public Scrutiny: Navigating Later Years**While Robert Mitchum often presented a facade of unshakeable nonchalance, particularly evident in his witty dismissals of his 1948 marijuana arrest, his later years revealed a more personal struggle. The public, which had long been fascinated by his anti-establishment charm and devil-may-care attitude, was given a glimpse into the toll that a lifetime in the public eye, combined with personal challenges, could take. In 1984, at the age of 67, Mitchum sought treatment for alcoholism at the Betty Ford Center in Palm Springs, California. This moment, though private, spoke volumes about the underlying pressures that even the most outwardly impervious stars faced, underscoring a vulnerability beneath the rugged exterior.

This later admission of a personal battle contrasted with his earlier, almost defiant, handling of the marijuana scandal, where he famously quipped that jail was “like Palm Springs, but without the riff-raff.” It highlighted a shift in the public’s perception of celebrity struggles and Mitchum’s own evolving approach to his personal health. While he continued to work prolifically in film and television, this period offered a more candid perspective on the man behind the legendary screen persona, revealing that even a seemingly invincible figure like Mitchum grappled with deeply human challenges.

His characteristic independence, a hallmark of both his personal life and career, remained. In 1991, for instance, Mitchum was slated to receive a lifetime achievement award from the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. However, in a move entirely consistent with his maverick spirit, he rejected the honor upon learning that he would be required to cover his own travel and accommodation expenses to accept it in person. This anecdote, like so many others throughout his life, underscored his refusal to conform to conventional Hollywood expectations, a trait that endeared him to many and further solidified his unique legend, demonstrating that his authenticity was not merely an act.

Read more about: 15 Unforgettable Gen X Movie Stars Who Left Us Too Soon, But Whose Legacies Shine Forever

11. **An Unforgettable Legacy: The Enduring Noir Star**Robert Mitchum’s journey from a restless, wandering youth to an undisputed giant of American cinema is a testament to an extraordinary blend of natural talent, an unyielding authenticity, and a captivating screen presence that remains as potent today as it was decades ago. His career, spanning over fifty years and encompassing an astonishing range of roles, left an indelible mark on Hollywood, defining the very essence of the antihero and becoming synonymous with the shadowy world of film noir.

His contributions did not go unnoticed by those who scrutinized the art of cinema. Film critic Roger Ebert, a discerning observer of Hollywood talent, famously called Mitchum his “favorite movie star and the soul of film noir,” beautifully articulating his enduring appeal: “With his deep, laconic voice and his long face and those famous weary eyes, he was the kind of guy you’d picture in a saloon at closing time, waiting for someone to walk in through the door and break his heart.” Similarly, David Thomson offered a powerful assessment, stating, “Since the war, no American actor has made more first-class films, in so many different moods,” underscoring the consistent quality and versatility that permeated Mitchum’s remarkable filmography.

The industry also recognized his singular impact with significant accolades. In 1984, his contributions to cinema were permanently etched into Hollywood lore with the unveiling of his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Eight years later, in 1992, he received the prestigious Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award, a lifetime achievement honor that celebrated his profound influence and extensive body of work, further solidifying his place among the pantheon of Hollywood legends.

His legacy continues to be measured and celebrated, ensuring his enduring relevance in cinematic discourse. The American Film Institute, in its esteemed ranking of the greatest male stars of classic American cinema, placed Robert Mitchum at number 23, a testament to his lasting power and iconic status. This recognition underscores not just the quantity of his work, but the profound quality and unforgettable impression he left on generations of filmgoers and filmmakers alike.

Read more about: Bruce Glover: A Retrospective on the Versatile Career of a Hollywood Character Actor, From 007 Villain to Esteemed Acting Coach

Ultimately, Robert Mitchum was more than just an actor; he was a phenomenon, a force of nature whose weary eyes and gravelly voice communicated a profound understanding of the human condition, particularly its darker, more complex facets. His unpretentious artistry, combined with a fiercely independent spirit, created a screen persona that embodied a unique blend of menace and vulnerability. He navigated Hollywood on his own terms, leaving behind an unparalleled body of work that continues to captivate and challenge, ensuring his place as an unforgettable star whose impact will resonate through the annals of film history for generations to come.