Rodrigo Moya, a masterful photojournalist whose lens intimately captured the tumultuous transformations of Latin America, passed away on July 30 at his home in Cuernavaca, Mexico. He was 91 years old. His son Pablo confirmed the cause of death as a stroke, marking the end of an extraordinary life dedicated to revealing the unvarnished truth of an era.

Mr. Moya distinguished himself by chronicling a tempestuous period in Latin American history, particularly the 1950s and ’60s. During this time of rapid modernization and single-party rule in Mexico, he meticulously documented poverty and widespread social unrest. His indelible images included iconic portraits of the Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara and the celebrated novelist Gabriel García Márquez.

Despite his photographs being regarded as among the most revelatory of his era, often compared favorably to the work of contemporaries like Héctor García Cobo and Nacho López, Mr. Moya largely remained a marginal figure for much of his career. Yet, his profound commitment to documenting reality, even when it contradicted official narratives, cemented his legacy as a photographer who used his art for conscience and truth.

1. **Early Life and Path to Photography**Born Luis Rodrigo Moya Moreno on April 10, 1934, in Medellín, Colombia, Moya’s early life was shaped by a blend of Colombian and Mexican influences. His father, Luis Moya Sarmiento, was a Mexican painter and set designer, while his mother, Alicia Moreno Vélez, managed the family home and indulged in amateur photography, an interest that subtly seeded Rodrigo’s future passion. The family relocated to Mexico City in 1937, where Rodrigo later attended the Colegio Madrid.

Moya briefly pursued an engineering program at the National Autonomous University of Mexico but ultimately dropped out in 1954, at the age of 20, seeking a different path for a living. His entry into photography was, by his own account, almost accidental. While working at a Mexican television studio, he met Guillermo Angulo, a Colombian photographer for *Impacto* magazine, who offered him photography lessons in exchange for instruction on operating a TV camera. It was within the darkroom at *Impacto* that Moya’s true calling became clear, inspiring him to commit to the craft.

Under Angulo’s mentorship, Moya began as an assistant and apprentice, learning the intricacies of the medium. This initial period was crucial in shaping his foundational skills and journalistic instincts. He was also influenced by Portuguese art critic Antonio Rodriguez, further broadening his perspective. This foundational experience at *Impacto* quickly led to opportunities, and within a year, Moya was hired as a staff photographer, setting the stage for his impactful career.

Read more about: Driving Expert’s ‘Clever’ Hack: Stop Tailgaters Safely Without Ever Touching Your Brakes

2. **Chronicling Mexico’s Modernization and Turmoil**Taking over Angulo’s chief photographer position at *Impacto* in 1955, Rodrigo Moya rapidly immersed himself in the socio-political landscape of Mexico. For the next thirteen years, his photojournalism took him across Mexico, collaborating with influential magazines such as *Sucesos*, *Siempre!*, *El Espectador*, and *Política*. He focused keenly on the country’s tempestuous period, particularly the 1950s and ’60s, a time marked by significant modernization and the entrenched single-party rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party.

Moya’s work during this era went beyond mere reporting; it was an active interpretation of a nation in flux. He sought to capture the profound essence of Mexico as it grappled with rapid change, meticulously documenting the societal shifts that were often overlooked or intentionally suppressed by official narratives. His images provided a stark, contrasting view to the idealized modern country the government aimed to promote.

In a revealing 2008 photo essay, Mr. Moya eloquently described the urban reality that captivated him, writing, “More than the beltways or the glass-covered skyscrapers that proliferated along the main avenues, the city that astonished me was one of textures, of mud and dust and improbable, precarious houses,” populated by “the millions who build the urban center, who pave it and sweep it” and “maintain the movements of the urban clockwork.” This quote vividly encapsulates his dedication to portraying the lived experience of ordinary Mexicans, a recurring theme throughout his extensive body of work.

3. **Documenting Poverty and Deprivation**Throughout his photojournalism career, Rodrigo Moya dedicated a significant portion of his work to documenting the widespread poverty and deprivation that often accompanied Mexico’s modernization. He was acutely aware of the social inequalities and popular struggles of the 1950s and 1960s, believing it was his role to capture these realities. Armed with two cameras – one for news assignments and another for his personal, more intimate observations – he traversed Mexico City, seeking out the unvarnished truth.

His subjects were the unsung heroes and the vulnerable: the hardworking shopkeepers, the innocent schoolchildren, and the resilient rural laborers. These individuals, often marginalized in official narratives, became central to Moya’s visual storytelling. He aimed to “document, explore and struggle to transform reality, to induce consciousness with moving or brutal photographs, of everyday topics but emotional,” using his assignments as opportunities to capture subjects he found interesting or moving.

Moya’s archive, comprising some 40,000 images, is a testament to his unwavering focus on the human cost of societal change. It is filled with images that acutely portray these struggles, providing a powerful visual record of the lives of the working class and the poor. Even though he later stopped photojournalism for a period, his early work stands as a crucial historical document of those turbulent times.

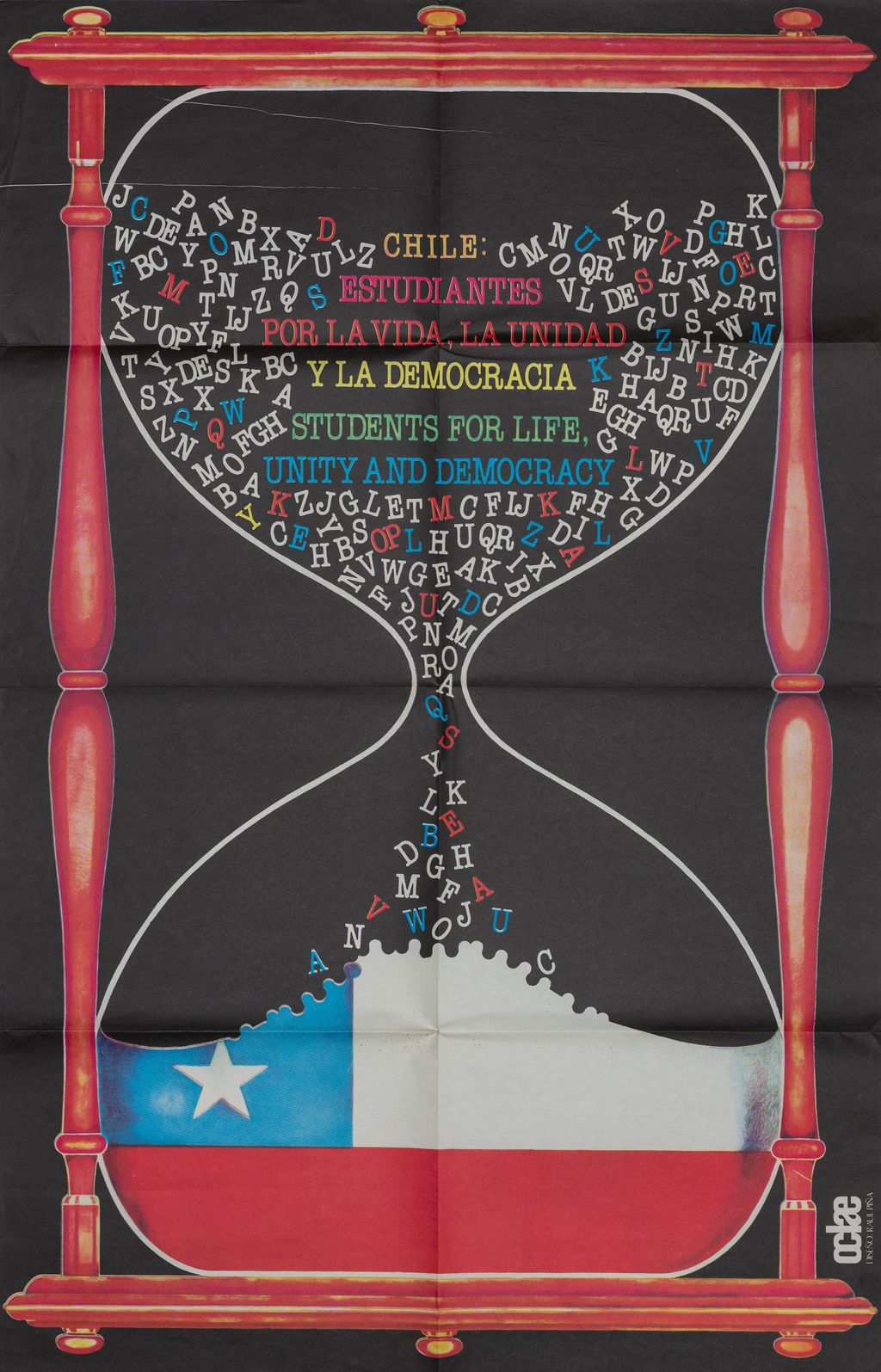

4. **His Controversial Unpublished Works**A significant aspect of Rodrigo Moya’s early career was the inherent conflict between his raw, unvarnished depiction of Mexican society and the official image promoted by the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party. Many of his photographs, particularly those that starkly illuminated deprivation, strikes, and student protests, were deemed too controversial for publication. These images directly contradicted the sanitized narrative of a rapidly modernizing and prosperous nation.

This censorship, whether external or internal through the self-censorship of the Mexican press, led Moya to stash away thousands of negatives for decades. These hidden works, later rediscovered, served as a powerful counter-narrative to the official media’s portrayal. They were a testament to his commitment to truth and his ideological stance, despite the professional consequences.

Moya’s willingness to capture these difficult truths, even when they could not be immediately shared with the public, underscores his profound dedication to documentary realism. His objective was not merely to report, but to create a visual record that mirrored the genuine “physiology of Mexico” and the “economic physiology of our countries,” even if that mirror reflected harsh realities that some preferred to ignore.

5. **Embedding with Guerrilla Movements in Latin America**Beyond his documentation of Mexico’s internal struggles, Rodrigo Moya, a committed Marxist, expanded his focus to photograph armed conflicts throughout Latin America. In the 1960s, inspired by the military success of the Cuban revolution, he documented the proliferation of guerrilla armies across the region, bringing a unique insider’s perspective to these volatile movements. This period marked a bold and dangerous phase of his career.

He fearlessly embedded with rebel groups in challenging environments, notably capturing fighters as they navigated the jungle in a shroud of fog in places like Guatemala and the Sierra de Falcón in Venezuela. In 1966, he traveled to the Venezuelan jungles, invited by the soldiers themselves, resulting in a powerful series titled “Guerrillas in the mist.” He also infiltrated a United Fruit Company (now Chiquita Brands International) estate in Panama to expose its miserable labor conditions, demonstrating his unwavering commitment to social justice.

Perhaps most notably, Moya was the only Latin American photographer to cover the U.S. Army’s invasion of the Dominican Republic in 1965, providing an invaluable and singular visual record of this critical historical event. His willingness to put himself in harm’s way to capture these moments cemented his reputation as a courageous and ideologically driven photojournalist, leaving behind an archive filled with images of numerous protests, revolutionaries, and people in difficult situations.

6. **The Iconic “Melancholic Che” Portrait**Among Rodrigo Moya’s most recognized and iconic works is his portrait of Che Guevara, famously known as “Melancholic Che” or “El Che melancólico,” captured in Havana, Cuba, in 1964. This image, showing a forlorn Guevara wielding a cigar with a sad expression, is one of only two truly iconic photographs of the revolutionary. Its creation was, by Moya’s own account, a fortunate happenstance, born from an unexpected turn of events during a Mexican delegation’s visit to Cuba.

Moya had traveled to Cuba with writer Froylán Manjarrez and cartoonist Rius in 1964, initially for a book project on the Cuban Revolution that ultimately never materialized. On the very last day of their four-week trip, a previously scheduled meeting with Fidel Castro was canceled, but unexpectedly, they were granted a 15-minute interview with Che Guevara. This brief slot turned into more than two hours, as Guevara, a fan of Eduardo del Río’s cartoons, engaged deeply with the delegation.

During this extended session, Moya had the rare opportunity to capture Guevara in a range of emotions, moving beyond the typical heroic portrayals. “The Che I photographed,” he stated in an interview for the 2007 book “Conversations With Mexican Photographers,” “was one without any historical makeup.” The resulting image revealed an unvarnished man, seemingly burdened by significant psychological baggage, offering a profound and humanizing glimpse into the revolutionary’s inner world.

7. **Capturing Other Political Figures and Unvarnished Truth**While “Melancholic Che” stands out, Rodrigo Moya’s political documentation extended to other significant figures across Latin America, always with his characteristic emphasis on an unvarnished truth. He continued to broaden his focus to photograph various luminaries, capturing their essence beyond their public personas. His discerning eye sought not just recognition but genuine human experience.

Among the pantheon of figures he photographed were the Cuban singer Celia Cruz, known for her vibrant stage presence, the distinguished novelist Carlos Fuentes, and the iconic painter Diego Rivera. In each portrait, Moya aimed to peel back layers of celebrity or political stature, seeking what he termed the “social contrasts” and the “physiology” of his subjects and their environments.

His philosophy was deeply rooted in the belief that photography was “the most intense approach to life, to the nature of the world, to the beings and things that entered through my lens and remain there.” This ethos meant that whether he was documenting guerrilla fighters or celebrated artists, his commitment remained to capturing the authentic human experience. He ensured that his photographs of these historical figures contributed to an essential legacy of memory and truth, documenting crucial historical processes with a profoundly humanist lens.

Having explored the foundational period of Rodrigo Moya’s career, from his formative years and initial groundbreaking photojournalism to his courageous documentation of revolutionary movements and iconic political portraits, we now turn our gaze to the later, equally compelling chapters of his life. His multifaceted journey extended far beyond the immediate lens of political strife, encompassing celebrity portraiture, a notable literary incident, a significant pivot in his professional life, and the eventual rediscovery of a vast, hidden archive that cemented his lasting legacy.

His photographic endeavors were not merely about capturing the headlines of political upheaval; they were deeply rooted in a humanist perspective, seeking the unvarnished truth of individuals and societies alike. Moya’s unique ability to transcend the immediate context and reveal the deeper human condition is a testament to his enduring impact, marking him as a photographer of profound ideological commitment and unwavering conscience.

Read more about: Britney Spears: Unpacking the Unbreakable Spirit of Pop’s Enduring Princess Through Her Rollercoaster Journey

8. **The Unforgettable Gabriel García Márquez Incident**Beyond the political figures and revolutionary leaders, Rodrigo Moya also left an indelible mark through his celebrity portraiture, one instance of which became a legendary moment in literary history. He had cultivated a friendship with the celebrated Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez, whom he had first met in the 1950s. This connection led to a truly unique photographic session in 1976 when García Márquez unexpectedly arrived at Moya’s doorstep in Mexico City, bearing a distinct black eye.

This striking facial injury, García Márquez explained, was the result of a punch delivered by fellow Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa just two days prior. The motive for this dramatic altercation was reportedly García Márquez’s interference in Vargas Llosa’s marriage. Moya, ever the documentarian, recognized the historical significance of the moment and readily agreed to photograph the novelist, not for publication at the time, but “as a matter of record.”

Moya vividly recalled the session, noting his initial concern for García Márquez’s “melodramatic face.” However, a sudden shift occurred: “Then suddenly something happened, I said something and he laughed, and I took two photographs.” One of these became the now-famous image of a battered yet grinning García Márquez. Moya held onto the negatives for over three decades, finally publishing the image in the Mexican newspaper *La Jornada* in 2007 on the author’s birthday, igniting years of literary speculation and gossip. This unexpected turn of events became one of Moya’s most talked-about photographs, one he humorously noted in an interview with *The Paris Review*, “I’ve never made so much money from a photograph.”

9. **From Lens to Ledger: The Shift to Publishing and Writing**By 1967, a significant shift began to take shape in Rodrigo Moya’s professional life. Following the death of Che Guevara, and coupled with a growing disillusionment with armed leftist movements and the pervasive self-censorship prevalent within the Mexican press, Moya made the consequential decision to largely step away from active photojournalism. His youthful and, as he later described it, “naive claim to photograph the guerrilla deeds vanished with the death of the commander.”

His pivot marked a new chapter, venturing into the realm of publishing. In 1968, Moya founded a small publishing company and launched a monthly trade magazine titled *Técnica Pesquera* (Fishing Technique). For the subsequent 22 years, until its closure in 1990, he dedicated himself to this enterprise, serving as its editor, writing extensively for its pages, and occasionally contributing his own photography. This venture allowed him to pursue his passion for research journalism and the sea, combining two of his great interests.

During these two decades, as he navigated the world of publishing, Moya amassed a large archive of photographs, an estimated 40,000 images, from his photojournalism career. These negatives, a silent testament to his earlier work, were carefully stored away in his home, largely untouched, awaiting a future rediscovery that would redefine his legacy.

10. **A New Chapter: His Literary Pursuits**Rodrigo Moya’s creative energies were not confined to visual storytelling and publishing; he also embarked on a significant literary journey, demonstrating a versatile talent that extended to the written word. In the 1990s, he ventured into short fiction, further expanding his artistic expression beyond the photographic frame. His debut short story collection, *De lo que pudo haber sido y no fue* (*What Could Have Been*), was published in 1996, marking his formal entry into the literary world.

A year later, in 1997, Moya’s literary prowess was formally recognized when his book *Cuentos para leer junto al mar* (*Stories to Read by the Sea*) was awarded a prestigious Mexican national literary prize by the National Institute of Fine Arts and Literature. This accolade underscored his ability to craft compelling narratives, showcasing a keen observational eye that translated seamlessly from images to prose.

Over his lifetime, Moya published a total of two short-story collections, along with numerous other writings. This aspect of his career revealed a deeper commitment to storytelling, whether through the stark realities captured by his lens or the imaginative worlds woven through his words, solidifying his identity not just as a photographer, but as a comprehensive chronicler of human experience.

11. **The Rediscovery of a Hidden Treasure: His Archive**The late 1990s brought a pivotal turning point in Rodrigo Moya’s life, leading to the unexpected rediscovery of his vast photographic archive. Diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 1999, Moya, along with his wife, Susan Flaherty, made the decision to move from Mexico City to Cuernavaca. This relocation provided the impetus for him to confront and explore the boxes filled with thousands of negatives that had remained largely untouched for nearly three decades.

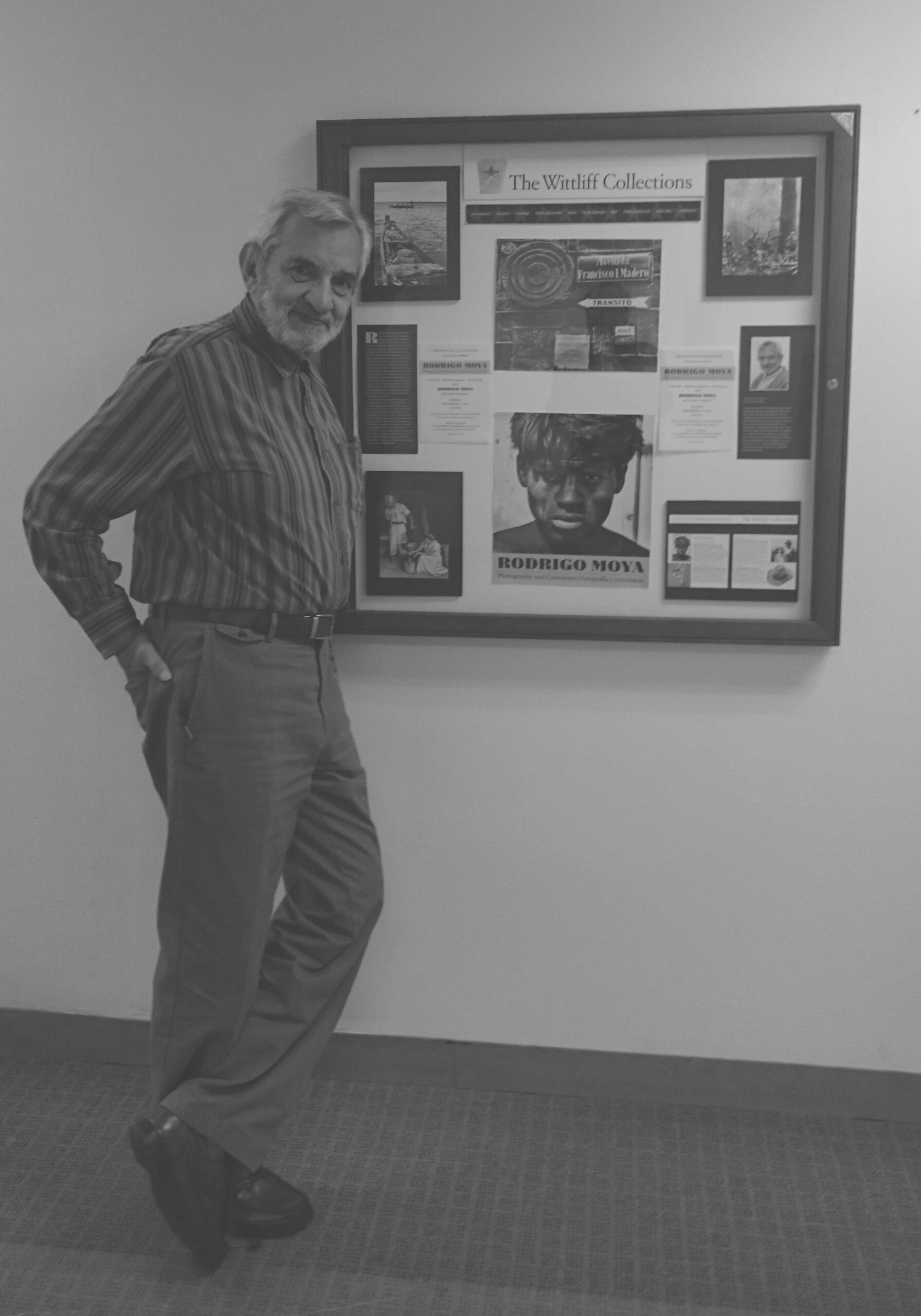

To his pleasant surprise, the archive, comprising some 40,000 images, was found to be in remarkable condition. This discovery prompted a collaborative effort: with the graphic design skills of his wife and the expertise of various photographic specialists, Moya began the painstaking process of reorganizing, cataloging, and promoting this vast body of work. This endeavor marked a significant shift, as he began to make a living from selling and exhibiting these long-dormant images, often expressing his surprise at which particular photographs resonated most with collectors, especially those in the United States, such as the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University.

Reflecting on this transformative period, Moya eloquently described the experience as akin to discovering his “own time machine.” This re-engagement with his past work not only offered him a renewed sense of purpose but also provided the world with an invaluable visual record of an era, allowing his profound documentary vision to reach a wider audience than ever before.

12. **A Second Life: Exhibitions and Publications**The re-evaluation and promotion of Rodrigo Moya’s photographic archive quickly breathed new life into his career, giving his work a much-deserved second act. In 2000, his first major public exhibition, titled “Fuera de moda” (Out of Fashion), debuted in Xalapa, Veracruz, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the Cuban Revolution. This critically acclaimed collection subsequently traveled internationally, with exhibitions in cities such as Milan, Algiers, Dublin, New Delhi, Vienna, and Havana, where he returned to Cuba for the exhibit.

His rediscovered work also became the subject of numerous publications, further solidifying his place in photographic history. Notable books dedicated to his oeuvre include “Foto Insurrecta” (2004), the first comprehensive research into his archive, and “Photography and Conscience/Fotografía y Conciencia” (2015), a bilingual volume published by the University of Texas Press. These publications, alongside widespread republication in books, magazines, and newspapers, brought his powerful imagery to a global audience, drawing comparisons from *The New Yorker* to the formal elegance of the Bauhaus movement, noting how his work avoided clichés with wit and restraint.

Despite this burgeoning recognition, Moya maintained a humble perspective, famously stating his preference for books about his works over exhibitions or awards. Nevertheless, his photographs now reside in the permanent collections of prestigious institutions such as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Wittliff Collections, ensuring his legacy continues to inspire and inform.

13. **Defining His Craft: A Documentary Realist, Not an Artist**Throughout his distinguished career, Rodrigo Moya held a clear and unwavering philosophy regarding his photographic practice. Despite the critical acclaim his work garnered from an artistic viewpoint, he consistently rejected the notion of himself as an “artist,” instead categorizing his work as “documentary, realist, humanist and ideologically committed.” This self-definition, which he maintained “for a long time” and vowed to “die with this commitment,” underscored his profound passion for photography rooted in social themes rather than mere aestheticism.

Moya’s formative influences were diverse, drawing inspiration from his parents, his mother’s amateur photography, and his father’s artistic background. He also avidly studied the works of renowned documentary photographers, citing figures such as Alfonso Morales Carrillo, Walker Evans, Lewis Hine, Robert Frank, Eugene Smith, Dorothea Lange, and the Farm Security Administration. Mexican photographer Nacho López was another significant influence, with Moya’s street photography of 1950s Mexico City often compared to López’s work in capturing everyday life.

His core objective was not to create beautiful images for their own sake, but to use the camera as a tool for deeper understanding and social change. Moya articulated this succinctly: his interest was to “document, explore and struggle to transform reality, to induce consciousness with moving or brutal photographs, of everyday topics but emotional.” He would often use his news assignments as opportunities to capture subjects he found personally interesting or moving, revealing the true “physiology of Mexico” and the “economic physiology of our countries,” a commitment he championed over the growing dominance of aestheticism in photography.

14. **Beyond the Frame: Personal Life and Family**While Rodrigo Moya’s public persona was largely defined by his impactful photojournalism, his personal life also played a significant role in shaping his perspective and experiences. Born in Medellín, Colombia, his early years were marked by a blend of Colombian and Mexican cultures, with his Colombian mother instilling a partial Colombian identity despite the family’s relocation to Mexico City in 1937. His family home became a vibrant gathering spot for Colombian artists and writers, including his friend Gabriel García Márquez, fostering an environment rich in intellectual and creative exchange.

Moya’s personal journey included two marriages. His first marriage was to Annunziata Rossi, a professor of literature at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, in 1959. This union, which ended in divorce in 1964, produced two sons, Pablo and Nicolás, and a daughter, Giovanna. Sadly, Nicolás and Giovanna Moya passed away earlier in his life, leaving him with the enduring presence of his son Pablo, who confirmed his father’s passing.

In 1982, Moya found companionship again, marrying Susan Flaherty, an illustrator who would become his life partner for 43 years. Susan played an instrumental role in his later life, particularly in the meticulous reorganization and promotion of his extensive photographic archive. Their shared life in Cuernavaca, where they moved in 1998, provided the tranquil setting for his later work and the rediscovery that ultimately brought his powerful body of work to wider recognition.

Read more about: Find Your Stride: Top Elliptical Machines for Any Home Gym Goal

15. **A Lasting Legacy: Humanist, Committed, Truth-Seeker**Rodrigo Moya’s passing at 91 on July 30, 2025, marked the end of an extraordinary life, but the beginning of an intensified appreciation for his profound and unvarnished legacy. His work, often compared favorably to masters like Henri Cartier Bresson and Manuel Álvarez Bravo, captured the very essence of a changing Latin America with a unique blend of courage, empathy, and ideological commitment. He did not merely photograph events; he documented the “social inequalities, popular struggles and revolutionary movements of the 1950s and 1960s,” creating a mirror where history still breathes.

His enduring philosophy, articulated with clarity, framed photography as “the most intense approach to life, to the nature of the world, to the beings and things that entered through my lens and remain there.” This belief manifested in his tireless pursuit of “social contrasts, people’s hardships, cities distortion,” and the “economic physiology of our countries,” ensuring that his images served a purpose beyond the aesthetic – that of conscience and truth. He refused many prizes and honors throughout his career, preferring to let his work speak for itself, a testament to his dedication to the message over personal acclaim.

Indeed, Rodrigo Moya’s subjects, whether they were farmworkers, guerrillas, or celebrated artists, were not just images on film; they were, in his own poignant words, “populating memory and the small surface of photographic paper, refusing to die, looking at me with the same eyes they looked at me with decades ago.” This powerful statement encapsulates the enduring impact of his lens: a legacy of memory and truth, preserved through thousands of negatives, ensuring that the turbulent, human story of Latin America will continue to resonate for generations to come.