Rosalyn Drexler, a singular and relentlessly inventive force in American arts and letters, died on Wednesday at her Manhattan home at the age of 98. Her passing marks the end of an extraordinary life that saw her navigate, and often master, an astonishing array of creative disciplines. She was an Obie Award-winning playwright, an Emmy Award-winning comedy writer, an acclaimed novelist, a lauded Pop Art painter, a found-objects sculptor, a self-described funky nightclub singer, a frequent book and film critic, and even, for a brief but memorable period, a professional wrestler.

Indeed, Ms. Drexler’s career was so profoundly multifaceted that, as Nora Ephron presciently observed in The New York Post in 1965, there was “a feeling among Rosalyn Drexler’s friends that she is carrying this Renaissance Woman bit a little too far.” Yet, as the subsequent decades would demonstrate, Ms. Drexler was just embarking on what would become a testament to boundless creativity, fueled by a simple philosophy: “It’s the same mind,” she stated in a 2017 Archives of American Art oral history interview. “The same humor and the intensity, once I get into a project. Just the actual enjoyment of doing the thing.”

Her life story is a vivid tapestry woven from disparate threads, each strand representing a fully embraced endeavor that defied conventional categorization and expanded the very definition of an artist in the 20th and 21st centuries. We embark on an in-depth examination of the primary facets of this remarkable individual’s existence, beginning with some of the most distinctive and impactful chapters that defined her enduring legacy.

1. **Onetime Professional Wrestler: Rosa Carlo, the Mexican Spitfire**Perhaps one of the most unexpected and enduring facets of Rosalyn Drexler’s early life was her brief but impactful career as a professional wrestler. This unusual chapter began in the early 1950s when she and her husband, Sherman Drexler, resided in Hell’s Kitchen, Manhattan. Their proximity to Bothner’s Gymnasium, a training ground for female professional wrestlers, piqued her interest. A friend suggested she try her hand at wrestling, and Ms. Drexler, ever the experimenter, began working out at the gym, quickly learning the intricate art of wrestling without injury and the crucial skill of making maximum noise to amplify the drama of her performance.

Adopting the vivid moniker “Rosa Carlo, the Mexican Spitfire”—a name she reportedly chose by flipping through a phone book—Ms. Drexler joined a traveling wrestling troupe. She toured for three months, grappling in unconventional venues such as a graveyard and an airplane hangar, demonstrating a remarkable adaptability and daring spirit. This period was not without its challenges; Ms. Drexler was deeply disturbed by the pervasive racism she encountered in the southern states, including segregated seating and water fountains, which ultimately led to her return home.

Despite the difficult aspects of the experience, Ms. Drexler recognized its unique value. Her time as Rosa Carlo became the direct inspiration for her critically acclaimed 1972 novel, “To Smithereens,” which she wrote with the pragmatic view that she “should at least get a book out of it” since she had disliked the experience. This novel later served as the basis for the 1980 film “Below the Belt.” The producers, intrigued by her wrestling background, consulted her on the title, to which she noted it was “not a wrestling title at all,” but they found it “sexy.” Even decades later, at 54, Ms. Drexler’s athletic spirit remained, leading her to enter a powerlifting contest, though she did not win. Her wrestling persona also left a significant mark on the art world, with Andy Warhol creating a series of silkscreen paintings based on a photograph of Ms. Drexler as Rosa Carlo, cementing this vibrant identity in pop culture history.

2. **Found-Objects Sculptor: Early Artistic Explorations**Before she became known as a Pop Art painter, Rosalyn Drexler embarked on her artistic journey as a sculptor, utilizing found objects to create distinctive assemblages. This period began during her brief residence in Berkeley, California, where her husband was completing his art degree. It was here that Ms. Drexler started collecting various discarded materials, transforming them into sculptures for display in her home. These early works were characterized as plaster accretions, built around armatures of scrap metal and wood, and they resonated with the informal, Abstract Expressionist-influenced Beat sculpture prevalent at the time.

Her talent quickly garnered attention. In 1955, Ms. Drexler held her first exhibition, showcasing her sculptures alongside her husband’s paintings. Upon their return to New York City, she continued to exhibit, encouraged by prominent figures such as sculptor David Smith and art dealer Ivan Karp. Smith, in particular, provided crucial support, urging her not to abandon sculpture, noting, “Don’t give up sculpture; I’ve known women sculptors and they stop; don’t stop.” Her works were shown at the Reuben Gallery in New York in 1960, where she also participated in Happenings, further cementing her presence in the burgeoning avant-garde scene. Her art earned praise from leading figures of the New York School, including Franz Kline.

Critics responded to these early sculptures with a mix of fascination and admiration, describing them as “ridiculous and nutty” yet revealing a “real beauty beneath their I-don’t-care attitudes.” Despite this recognition, a significant challenge arose when the Reuben Gallery closed after just one year. Ms. Drexler observed a stark disparity: all the male artists represented by the gallery received other offers, but she did not. Attributing this, somewhat naively in her later reflection, to her chosen medium rather than her gender, she made a pivotal decision to shift her focus to painting, hoping to secure more opportunities and a broader platform for her creative expression. This transition marked the beginning of another transformative phase in her artistic career.

3. **Lauded Pop Art Painter: The Emergence of Her Unique Style**Rosalyn Drexler’s pivot from sculpture to painting in the early 1960s coincided with the nascent stages of the Pop Art movement, a scene in which she rapidly became a central, albeit often overlooked, figure. Her approach to painting was decidedly innovative and self-taught, setting her apart from her peers. She would meticulously search through old magazines, posters, and newspapers, sourcing imagery that she then had blown up, collaged onto canvas, and finally layered with intensely vibrant, saturated colors. Her palette frequently featured cerulean blues, cadmium reds, and Day-Glo yellows, applied with a boldness that amplified the visual impact of her chosen subjects. Notably, she also held a peculiar fondness for Elmer’s Glue, proclaiming that it “doesn’t get enough credit for its role in art.” Throughout this productive period, Ms. Drexler famously never operated a dedicated studio, instead working wherever she could, typically within her home.

Her unique style and compelling subject matter quickly found a home. Drexler signed with the Kornblee Gallery, which hosted her solo shows from 1964 to 1966. A significant moment arrived in January 1964 when her work was featured in the “First International Girlie Exhibit” at Pace Gallery in New York. In this groundbreaking show, she and Marjorie Strider were the only two women Pop artists included alongside renowned figures like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Tom Wesselmann. Her contributions, collages crafted from “girlie magazines,” elicited a strong reaction, “scandalizing some” while largely being “well received” by critics. One observer noted that her “collage paintings…fly through contemporary life and fantasy with a virtuosic, uninhibited imagination that is refreshingly direct in its frank expression of brutality, desire, pathos and playfulness.”

Ms. Drexler’s paintings frequently tackled controversial and often unsettling themes, including physical violence, particularly against women, as seen in works like “Put It This Way” (1963), which depicts a man slapping a woman, or “Rub Out” (1982), showing a dead man with blood spots. Other works like “Time Trap” (1963), showing a man with a gun in a clock, reflected her view that “Everybody is trapped in time…you can’t shoot your way out of it.” These subjects, which also included racism and social alienation, were notably stark in a genre often lauded for its “cool” and detached sensibility. Although her work has more recently been identified as early feminist art, Ms. Drexler herself reportedly objected to this categorization, denying any deliberate political message. Nevertheless, her commitment to social justice was evident when she signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge in 1968, refusing tax payments in opposition to the Vietnam War, signaling a deeper current of engagement beneath the surface of her vibrant Pop canvases.

4. **Obie Award-Winning Playwright: Queen of the Underground Drama**Rosalyn Drexler’s prolific career extended profoundly into the realm of theater, where she earned significant acclaim as an Obie Award-winning playwright. Her distinctive voice and willingness to challenge conventional narratives made her a formidable presence in the avant-garde theatrical landscape, leading Clive Barnes, then chief theater critic of The New York Times, to famously pronounce her “the queen of the underground drama.” Over the course of her career, Ms. Drexler penned ten plays, each bearing the characteristic wit and unique perspective that defined her multidisciplinary output.

Her first major recognition came in 1964, when “Home Movies,” an evening comprising two one-act musicals, won an Obie for distinguished play. This award underscored her innovative approach, even if Louis Calta, reviewing it for The New York Times, had found it “contrived and dotty.” Such mixed reactions were often characteristic of groundbreaking work, challenging audiences and critics alike to expand their understanding of what theater could be. Ms. Drexler’s consistent innovation was further acknowledged when she received the Obie Award twice more, decades later.

In 1979, she was honored again for “The Writer’s Opera,” a work that explored the intricate and often conflicting dual role of a woman as both an artist and a mother. This play exemplified her ability to weave personal and societal observations into her dramatic narratives, offering poignant commentary on the challenges faced by women artists. Her third Obie arrived in 1985 for “Transients Welcome,” a collection of three one-act plays, further solidifying her reputation as a leading figure in experimental American theater. Her plays were produced in various esteemed venues, from the Judson Memorial Church and Provincetown Playhouse to the Theatre for the New City and the Manhattan Theatre Club, demonstrating the breadth of her theatrical footprint and her enduring influence on the off-off-Broadway movement.

5. **Acclaimed Novelist: Exploring the Human Condition with Farce and Wit**Rosalyn Drexler’s literary endeavors as a novelist were as varied and distinctive as her other artistic pursuits, cementing her reputation as an acclaimed writer capable of exploring the human condition with both profound insight and uproarious farce. Her writing career, in her own recollection, began subtly, by putting her parents’ arguments on paper to present them with evidence, a practice that, though met with destruction of the evidence, evidently honed her narrative instincts. She consistently expressed a lifelong desire to be a writer, a dream she realized with remarkable success, ultimately penning nine novels that spanned a wide range of subjects and styles.

Her debut novel, “I Am the Beautiful Stranger,” published in 1965, quickly garnered significant attention. Written in the unconventional form of a diary kept by a teenage girl residing in the Bronx, the book resonated deeply with critics. The author Terry Southern famously compared Ms. Drexler to J.D. Salinger, a testament to the novel’s compelling voice and nuanced portrayal of adolescent life. Richard Gilman, writing for The Times Book Review, lauded the work as “enormously replenishing,” highlighting its refreshing authenticity and impact on readers.

Ms. Drexler continued to push narrative boundaries with her subsequent novels. “The Cosmopolitan Girl” (1975) stands out as a memorable farce, chronicling the mutually affectionate and consensual love affair between a single woman and a talking dog, showcasing her distinctive humor and willingness to explore the absurd. Her 1972 novel, “To Smithereens,” drew directly from her personal experience as a professional wrestler, telling the story of a woman who becomes a wrestler. Although it received mixed reviews upon its initial release, its innovative premise inspired the 1980 movie “Below the Belt.” Another notable work, “One or Another” (1970), depicted a married woman’s affair with a high school adolescent, prompting one critic to describe it as “Kafka as interpreted by the Marx Brothers,” a comparison that speaks volumes about her unique blend of existential themes and comedic sensibility. This rich body of work firmly established Rosalyn Drexler as a novelist whose narratives were consistently engaging, provocative, and utterly her own.

6. **Emmy Award-Winning Comedy Writer: A Prowess for Television**Beyond the stages of experimental theater and the pages of acclaimed novels, Rosalyn Drexler also made a significant, award-winning impact in the world of television comedy. Her talent for crafting incisive and engaging narratives translated seamlessly to the screen, earning her one of the industry’s most prestigious accolades. In 1974, she shared a writing Emmy Award for her contributions to “Lily,” a Lily Tomlin comedy special. This recognition placed her among an exceptionally distinguished group of collaborators, including comedic giants like Richard Pryor and Lorne Michaels, underscoring the high caliber of her writing in this dynamic medium.

“Lily” itself was a groundbreaking production, celebrated for its innovative comedic approach and its star’s versatile performances. The special ultimately won the Emmy for outstanding comedy-variety, variety, or music special, a testament to the collective creative force behind it, in which Ms. Drexler played a pivotal role. The episode that earned her the shared Emmy was the 1973 CBS comedy special starring Lily Tomlin, Alan Alda, and Richard Pryor, for which Drexler was one of 15 writers. This achievement not only marked a notable moment in her career but also highlighted her versatility, demonstrating an ability to excel in diverse creative environments, from the intimate settings of off-Broadway plays to the broad reach of network television. Her work on “Lily” provided a platform for her sharp wit and observational humor to reach a vast audience, further cementing her status as a true polymath in the entertainment industry.

7. **Film Novelizations: The Julia Sorel Persona**Adding another intriguing layer to her already remarkably diverse portfolio, Rosalyn Drexler ventured into the realm of film novelizations, often working under the pseudonym Julia Sorel. This particular branch of her writing career showcased her adaptability and keen storytelling ability, enabling her to translate cinematic narratives into compelling literary form. Her most widely recognized effort in this genre was the novelization of “Rocky” (1976), the Oscar-winning film based on Sylvester Stallone’s screenplay. The assignment to novelize a story about a boxer held a particular resonance for Drexler, as she herself possessed personal experience in the ring from her days as a professional wrestler, lending an authentic, if perhaps understated, connection to the material. As the context noted, “The assignment made sense; she had experience in the ring.”

Under the Julia Sorel nom de plume, Ms. Drexler’s work extended beyond the iconic boxing saga. She also adapted other screenplays into novels, further demonstrating her capacity to inhabit and expand upon existing narratives. Her other notable novelizations included “Dawn: Portrait of a Teenage Runaway” (1976), adapted from a screenplay by Dalene Young; “Alexander, The Other Side of Dawn” (1977), also adapted from a Dalene Young screenplay; and “See How She Runs” (1978), based on a screenplay by Marvin Gluck. This series of projects allowed Ms. Drexler to explore various storytelling styles and genres, reaching a broader commercial audience that might have been less familiar with her more experimental fine art or theatrical works. The pseudonym provided a clean division between her more personal artistic expressions and these commercial writing ventures, yet each project still bore the subtle mark of her profound literary talent and versatility.

In addition to the adapted screenplays, Ms. Drexler also penned an original novel, “Unwed Widow” (1975), under the Julia Sorel pseudonym, further illustrating the scope of this particular creative outlet. This body of work underscores her tireless dedication to writing in all its forms, whether for critical acclaim, artistic exploration, or to meet the demands of popular culture. Her ability to seamlessly transition between such disparate creative challenges is a testament to the unique and boundless nature of Rosalyn Drexler’s artistic spirit, a woman who truly embodied the concept of a Renaissance individual in the modern age.

8. **Major Artistic Themes: Beyond Pop Art’s Surface**While Rosalyn Drexler’s Pop Art featured vibrant colors and innovative collage, her deeper oeuvre consistently engaged with themes transcending the movement’s detached sensibilities. Her paintings often delved into darker undercurrents of American society, utilizing found imagery to provoke thought and highlight societal realities. This thematic depth positioned her work as both a reflection of her time and a commentary on enduring human issues.

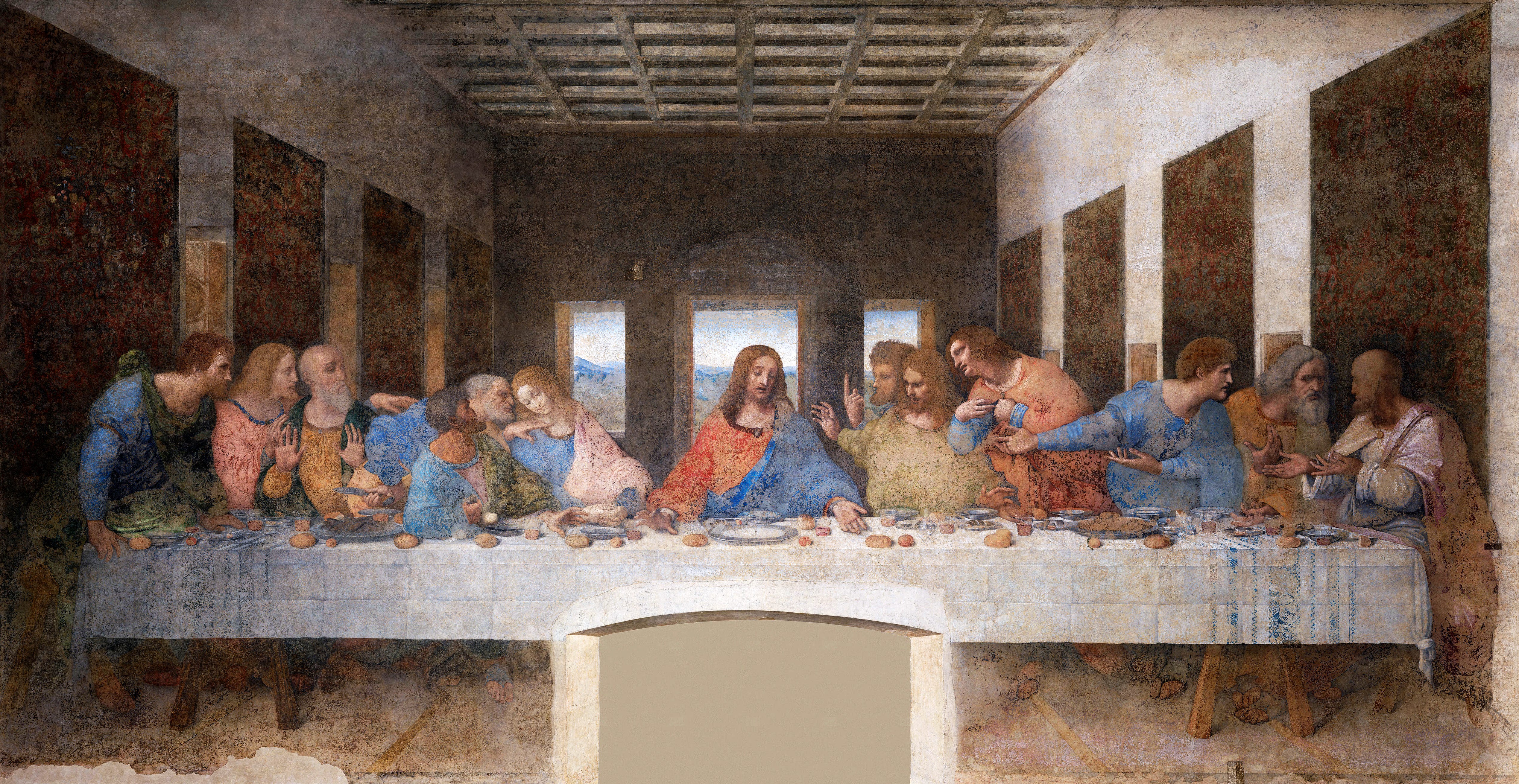

A significant body, the “Love and Violence” series, directly confronted abusive relationships between men and women. Canvases like “I Won’t Hurt You” (1964) and “Rape” (1962) starkly depicted sexual violence, drawing cues from pulp fiction and film noir. These unsettling narratives challenged viewers to confront such brutality. Drexler also explored ambiguous power dynamics in works such as “Kiss Me, Stupid” (1964).

Beyond interpersonal conflict, Drexler addressed broader social and political concerns. Her 1966 painting, “Is It True What They Say About Dixie?,” powerfully responded to the Birmingham race riot of 1963. Inspired by a newspaper photograph, its ironic title commented on racial violence. Similarly, “F.B.I.” (1964) critiqued government agents, while her “Men and Machines” series explored Cold War-era technological advancements. This diverse scope rooted her Pop aesthetic in critical engagement, making her work resonate with profound truth.

9. **The Distinctive Creative Process: A Life Without a Studio**Rosalyn Drexler’s artistic output stemmed from a distinctive creative process, born of necessity and ingenuity. She famously never maintained a dedicated studio, creating potent art from within her daily life, typically her Manhattan home. This adaptability underscored her unconventional spirit, viewing the world as her workspace, driven by the “enjoyment of doing the thing” she often spoke of.

Her self-taught painting technique was highly original. Ms. Drexler meticulously scoured old magazines and newspapers for imagery, which she then enlarged, collaged onto canvas, and layered with vibrant, saturated colors. This layered approach, combining found and fabricated elements, defamiliarized public media, transforming banal images into objects of profound contemplation. Her chosen palette amplified the visual impact, creating cohesive narratives from disparate elements.

An endearing aspect was her fondness for Elmer’s Glue, stating it “doesn’t get enough credit for its role in art.” This embrace of everyday substances, combined with innovative methods, forged a creative identity eschewing traditional artistic boundaries. Furthermore, her early exposure to art reproductions from newspapers influenced her later practice of sourcing imagery from popular media, demonstrating a continuous engagement with the democratized image.

Read more about: Unpacking Your Pint: A Healthline Deep Dive into Beer’s Nutritional Profile and Dietary Implications

10. **Literary and Critical Contributions: A Sharp Eye on Culture**Beyond her prolific artistic output, Rosalyn Drexler maintained a significant presence as an incisive commentator on contemporary culture through her journalistic and critical writings. Her discerning eye and sharp wit found outlets in various publications, including The New York Times, where she frequently contributed book and film reviews. This facet of her career underscored her intellectual breadth, engaging with the arts not only as a creator but also as a thoughtful analyst.

Her reviews were characterized by candor and strong opinions. She found Fay Weldon’s novel “The Life and Loves of a She-Devil” “scintillating,” appreciating bold narratives. Conversely, she dismissed the Barbra Streisand movie “Up the Sandbox” as “a rip‐off giving lip service to authentic concerns but copping out in the end.” These assessments reflected her commitment to artistic integrity and her willingness to offer pointed critique.

Ms. Drexler’s engagement extended to writing letters to the editors, demonstrating her active role in cultural conversations. Her willingness to defend works she admired, like the film “Billy Jack,” showcased an independent spirit and conviction in her aesthetic judgments. Her critical voice provided valuable insight into her intellectual framework, solidifying her reputation as a comprehensive figure in American arts and letters.

11. **The Funky Nightclub Singer: An Overlooked Chapter**Among Rosalyn Drexler’s diverse pursuits, her relatively low-key and short-lived career as a nightclub singer stands as an intriguing, often overlooked, chapter. This venture, beginning in 1973, further cemented her image as an artist unwilling to be confined by any single medium. It was another manifestation of her boundless desire to “enjoy the thing,” irrespective of aligning with established artistic identities.

Describing herself as a “funky nightclub singer,” Ms. Drexler embraced this persona with characteristic zest. Her performances took place in popular Manhattan cabarets, most notably Reno Sweeney, a venue known for eclectic talent. This choice perfectly aligned with her experimental spirit, providing a platform where her unique voice could find an appreciative audience, however fleeting.

While details of her repertoire or critical reception are less documented, its mere existence speaks volumes about her fearless approach to creativity. It underscored her belief in a unified artistic mind, where the intensity and humor fueling her writing and painting could channel into vocal performance. This brief period adds a vibrant splash to her life, reminding us that Drexler truly lived her philosophy of creative fluidity, unafraid to step onto any stage for self-expression.

12. **Reinvention and Artistic Fluidity: Defying Categorization**Rosalyn Drexler’s career was a profound testament to artistic fluidity, a relentless reinvention defying easy categorization. From professional wrestler to acclaimed painter and writer, she moved between disciplines with ease, confounding observers. This adaptability stemmed, as she explained, from “the same mind” channeling its “same humor and the intensity” into varied projects, driven by the “actual enjoyment of doing the thing.”

The difficulty in pinpointing Ms. Drexler’s professional identity was a recurring theme. Program biographies described her as “a well-known artist,” while reviews identified her as “novelist, writer and painter.” Art in America magazine noted her “unusual fluidity in terms of creative identity.” Her swift shift from sculpture to painting, in pragmatic pursuit of more opportunities, exemplified this continuous evolution.

Nora Ephron’s 1965 observation, that Drexler was “carrying this Renaissance Woman bit a little too far,” proved an understatement. Ms. Drexler was not merely dabbling; she deeply engaged with, and excelled in, each new medium. Her polymathic existence challenged conventional artistic specialization, asserting a holistic view of creativity where all forms are interconnected. Her refusal to be confined by genre or expectation created a legacy of boundless exploration.

13. **The Late-Career Reappraisal: A Resurgent Star**For many years, Rosalyn Drexler’s pioneering Pop Art contributions remained in shadow, her work described as a “secret kind of thing.” However, the latter part of her life witnessed a crucial and deserved late-career reappraisal, dramatically expanding recognition of her significant impact. This resurgence rectified a historical oversight, bringing her distinct voice and vision to a broader contemporary audience and securing her place within the canon.

A pivotal moment was her inclusion in the 2015 Tate Modern exhibition, “The World Goes Pop.” This groundbreaking show expanded Pop Art’s conventional understanding, including overlooked international and female artists. Drexler’s presence signaled a turning point, affirming her status as a key, albeit previously underrecognized, artist. Following this, her work became increasingly sought after by major American institutions, with MoMA, the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, and the Whitney Museum acquiring her paintings.

Further testament came with exhibitions like “Occupational Hazard” (2017) and a retrospective at Brandeis University’s Rose Art Museum (2018). These platforms allowed new generations of critics and curators to engage with her vision. The New York Times also named her republished 1972 novel “To Smithereens” one of the best books of 2025 so far. Ms. Drexler expressed bittersweet surprise at this late recognition, yet this comprehensive reappraisal has firmly etched her legacy into American art and literature.

14. **Critical Acclaim and Enduring Impact: The Critics Weigh In**As Rosalyn Drexler’s work gained renewed attention, critics articulated the profound nature of her impact, underscoring her unique position in American art and culture. Their analyses helped move her from an “obscure figure” to a recognized “key artist associated with the Pop art movement,” unraveling the complexities of her oeuvre and contextualizing her singular contributions.

The critic John Yau, reviewing her 2017 “Occupational Hazard” show, captured Drexler’s talent: “Nothing you see in her work should fit together, but it does.” He wrote that she “brought a lively imagination to bear on the banal and absurd images that dominate our lives…and made them into something to contemplate,” highlighting her transformative power. Bradford Collins echoed this, quoting Robert Storr: “It is the fate of some artists to arrive at the station on time, and still find themselves being left on the platform.” This metaphor depicted her long-delayed recognition.

Early in her career, Ms. Drexler’s idiosyncratic worldview fascinated observers. Jack Kroll suggested in “Who Does She Think She Is?” that “Her essential insight is that people and things are completely insane, and she speaks from inside the whale.” Initial pronouncements, like Nora Ephron’s “Renaissance Woman bit” remark, have evolved into a recognition of her extraordinary artistic breadth, establishing her as an artist of enduring significance.

15. **Legacy of a Polymath: An Enduring Inspiration**Rosalyn Drexler’s passing at 98 marked the culmination of an epoch-defining career characterized by boundless creativity and a steadfast refusal to conform. Her legacy is that of a true polymath, a singular artistic force who transcended conventional boundaries, leaving an indelible mark across an astonishing array of disciplines. She demonstrated, unequivocally, that the creative impulse is not divisible by medium but flows from an integrated mind, capable of shaping diverse forms with equal intensity and humor.

Her journey, from professional wrestler to Pop Art icon, and from Obie-winning playwright to Emmy-winning comedy writer, serves as a powerful testament to an uninhibited imagination. Drexler’s life was a vibrant argument against artistic specialization, asserting the profound value of intellectual curiosity and continuous exploration. She proved that an artist could be simultaneously deeply engaged with popular culture and profoundly critical of it, wielding both wit and social commentary. The recent critical reappraisal of her work underscores the timelessness of her vision, with her paintings resonating with contemporary concerns and standing as powerful commentaries on the human condition.

Ultimately, Rosalyn Drexler’s life and work invite us to reconsider the very definition of an artist. She embraced every creative impulse, transforming personal experience and popular imagery into something profoundly new and resonant. Her legacy is not just a collection of diverse achievements, but a compelling philosophy of life—one that celebrates the joyous intensity of creation, the courage to defy categories, and the enduring power of a truly unfettered artistic spirit. Her story will continue to inspire and provoke, cementing her place as an irreplaceable figure in modern American culture.