Ross E. Rowland Jr., a self-made commodities magnate who traded the cutthroat world of Wall Street for the romantic allure of steam locomotives, dedicating his considerable wealth and unyielding passion to the preservation of America’s rail heritage, died on July 19 in Watertown, N.Y. He was 85. His wife, Karen Bendix, confirmed that the cause of death in a hospital was lung cancer. Mr. Rowland had made his home in nearby Sackets Harbor, on Lake Ontario.

From the high-stakes trading floors of New York to the thunderous tracks traversing the American landscape, Mr. Rowland carved out a unique legacy. He was a man driven by a singular dream: to keep the magnificent engines of yesteryear alive and roaring. For decades, he was a prime mover behind some of the most celebrated and ambitious steam-train excursions in history, transforming a childhood fascination into a national spectacle.

His connection to the rails was deeply rooted, a familial inheritance stretching back generations. Born on July 11, 1940, in Albany, N.Y., Ross Ellsworth Rowland Jr. was the son of Ross E. Rowland Sr. and Helen (Jackson) Rowland. His father, a railroad worker for the Central Railroad of New Jersey, instilled in him an early appreciation for the iron giants. The family moved to Cranford, N.J., where young Ross found his true calling among the behemoths of the rail yard.

As a teenager, he gravitated towards the bustling rail yard near his home, becoming, in his own words, “something of a mascot to those who worked there.” This early immersion allowed him to move beyond mere observation; “Eventually they trusted me to help lubricate the trains,” he recalled in 1994, adding, “It was so exciting because I was helping maintain steam locomotives.” This hands-on experience cemented a lifelong devotion.

At the tender age of 14, a disagreement with his parents led him to run away from home. His journey took him to California, where he found employment at a luxury resort. It was there that he crossed paths with the legendary actor John Wayne, who hired him as a driver. After three years, however, Mr. Wayne offered a pivotal piece of advice, telling young Ross to return to his mother. He heeded the counsel, completing high school upon his return to New Jersey.

Echoing the path of higher education, Mr. Rowland followed a friend to Wall Street, a decision that would unexpectedly fuel his passion. There, he founded Floor Broker Associates, a firm that would grow into one of New York’s largest commodities brokerages, executing trades for prominent investment firms. His financial acumen also led him to serve on the board of directors for COMEX, a major precious-metals investment firm.

Yet, for Mr. Rowland, his burgeoning financial empire was not an end in itself but a means to a far more profound purpose. It provided him with the wherewithal to chase a dream many considered obsolete: the revival of American steam-train tradition. His substantial fortune became the engine, quite literally, behind his grand railroad endeavors.

In 1966, he transformed his personal passion into a public spectacle by founding the High Iron Company. This pioneering venture began offering thrilling excursions around the Mid-Atlantic States. These were not leisurely trots; Mr. Rowland envisioned and delivered “full-tilt sprints” behind half-a-million-pound engines, delivering an experience akin to a “thoroughbred race,” far removed from a mere “pony ride.

His timing was remarkably prescient. By the late 1960s, steam trains had largely been eclipsed by diesel technology, and overall rail traffic had declined significantly. This downturn, paradoxically, created an opportune moment for enthusiasts like Mr. Rowland, as it left ample room on the tracks for private excursions. From his office, located in a converted train station in Lebanon, N.J., he orchestrated memorable journeys, taking passengers from Hoboken up the Hudson River or across northern New Jersey to Port Jervis, N.Y., along the Delaware River.

Among his early triumphs was the Golden Spike Centennial Limited in 1969. Mr. Rowland was the driving force behind this ambitious project, which transported passengers from New York City’s Grand Central Terminal all the way to Promontory, Utah. The journey commemorated the 100th anniversary of the completion of the first transcontinental railroad, a monumental achievement in American history.

For this historic journey, Mr. Rowland utilized the formidable Nickel Plate Road 2-8-4 759. The expedition gained further notoriety with the participation of John Wayne, who rode along from New York to Salt Lake City. The actor shrewdly tied the train’s arrival to the local debut of his 1969 film “True Grit,” showcasing Mr. Rowland’s knack for blending grand spectacle with public engagement.

A few years later, inspired by the success of the Golden Spike, Mr. Wayne suggested an even grander undertaking: a national tour to celebrate the country’s upcoming bicentennial. Mr. Rowland seized upon this idea, leading to the creation of his magnum opus, the American Freedom Train.

Launched in 1975 and continuing through 1976, the American Freedom Train was a traveling museum unlike any other. It featured choice artifacts on loan from the Smithsonian Institution, including such priceless items as George Washington’s personal copy of the Constitution and Joe Louis’s boxing trunks, transforming a train into a moving testament to American history and achievement.

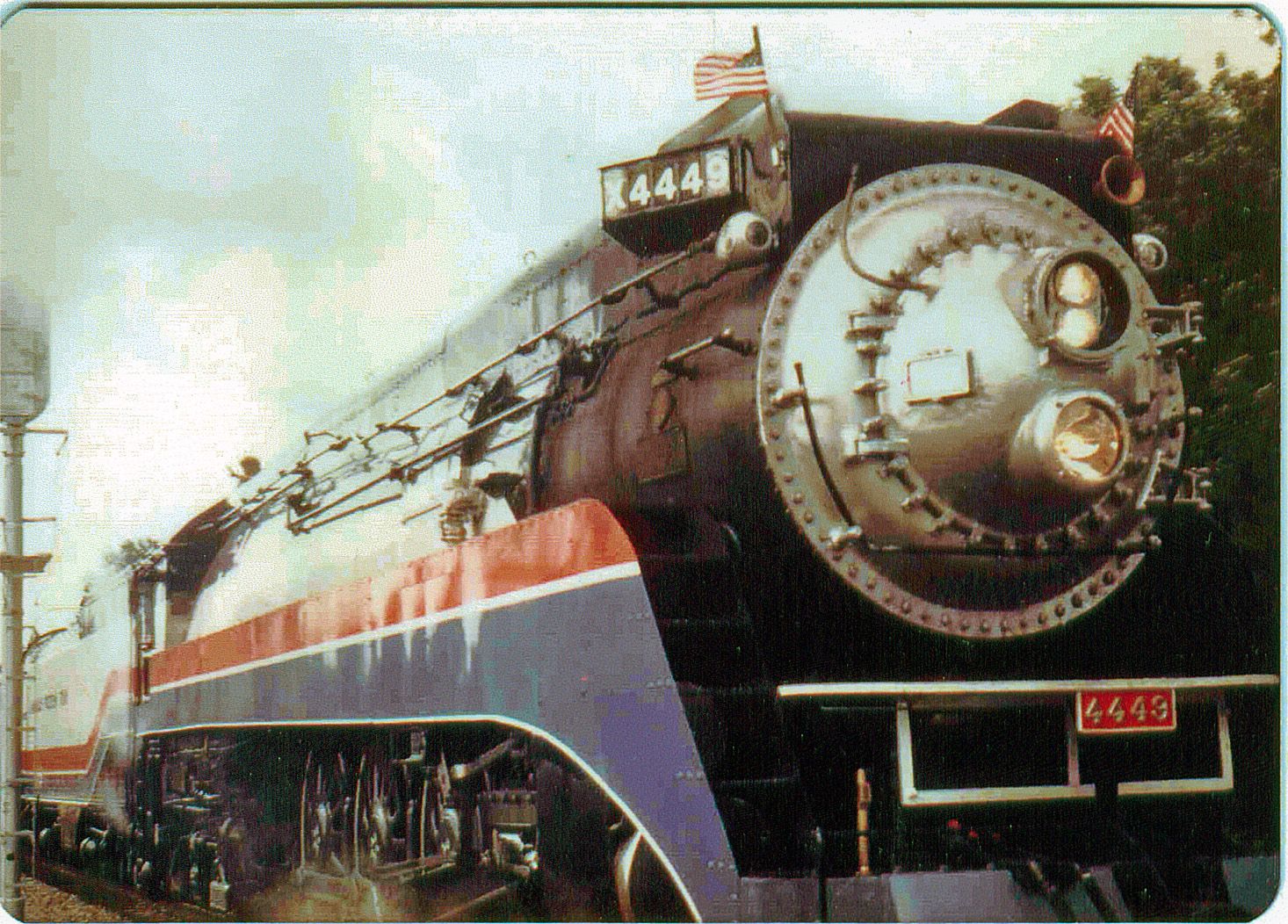

This monumental undertaking saw the train cruising through all 48 contiguous states. The eastern U.S. operations were proudly pulled by Mr. Rowland’s own ex-Reading 4-8-4 No. 2101, re-liveried as AFT No. 1, while the western operations were handled by the iconic Southern Pacific Daylight 4-8-4 No. 4449, under the direction of Doyle McCormack, and also Texas & Pacific 2-10-4 610.

The American Freedom Train proved to be an overwhelming triumph, drawing millions of paying customers to its stops in 138 cities across the nation. More than 7 million people visited the exhibit train, and tens of millions more gathered trackside to witness the majestic spectacle pass by, solidifying its place as a high point in Mr. Rowland’s career and in the annals of steam-driven tourism.

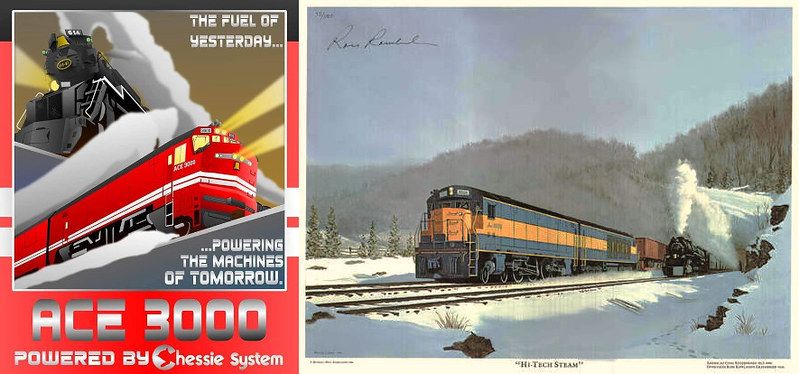

Following the bicentennial success, Mr. Rowland continued his partnership with steam. After the American Freedom Train concluded, his ex-Reading No. 2101 was pressed into service for the Chessie Steam Special, running a series of excursions throughout the Chessie System’s vast network in 1977 and 1978. This venture covered much of the railroad’s 20,000-mile expanse, just preceding Chessie’s 1980 merger that formed CSX Transportation.

Tragedy struck in March 1979 when the 2101 was severely damaged in a roundhouse fire in Kentucky. In compensation, Chessie System provided Mr. Rowland with the Chesapeake & Ohio 4-8-4 No. 614. Built by Lima in 1948 for C&O passenger service and previously displayed at the B&O Museum in Baltimore, this magnificent locomotive became his “pride and joy.” He bought and refurbished it that same year, returning it to service in 1980 to lead another system tour, the Chessie Safety Express.

Mr. Rowland’s vision extended beyond preservation; he harbored a profound belief in the future viability of coal-powered steam trains, especially during the era of high oil prices in the 1970s and ’80s. This conviction led him to spend a “considerable sum” on an ambitious project named ACE 3000, short for American Coal Enterprises.

The ACE 3000 was conceived as a high-tech steam locomotive, a purported answer to the energy crisis. Although the project never financially “got off the ground” and ultimately proved unworkable as a commercial venture, Mr. Rowland pressed on. In January and February 1985, he used the 614, re-numbered as 614-T, as a test bed for the ACE 3000 concept, pulling CSX coal trains through West Virginia’s challenging New River Gorge in the middle of winter.

His dedication to railroading was recognized beyond his private ventures. During the mid-1980s, Mr. Rowland served on Amtrak’s board of directors, lending his unique expertise and passion to the national passenger rail system. His deep connection with locomotive operations also earned him an honorary lifetime membership in the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, a point of considerable pride for him.

Despite the setbacks of ACE 3000, Mr. Rowland remained undeterred in his grand ambitions. He made multiple attempts in the 1990s and 2000s to replicate the national success of his earlier projects. Among these were the 21st Century Limited, intended to mark the turn of the millennium, which, after years of planning, unfortunately went bankrupt.

Another short-lived endeavor was the Pacific Wilderness Railway, which operated for just over a year in 2000 and 2001 on Vancouver Island in Canada. A decade later, he unsuccessfully tried to run a luxury train service from Washington, D.C., to the famous Greenbrier Resort in West Virginia. His plans also included the Yellow Ribbon Express to honor veterans and the Greenbrier Presidential Express.

Even in his final decade, Mr. Rowland’s spirit for grand rail projects burned bright. He passionately tried to drum up support for yet another iteration of the American Freedom Train, this time intended to commemorate the country’s 250th birthday, the Semiquincentennial. His wife indicated that he had finally begun to garner support in Washington for this latest dream when he received his cancer diagnosis, leaving the prospects for another American Freedom Train currently unclear.

His lifelong devotion was perhaps best encapsulated in his own words to Trains.com in 2018: “Compared to any steam engine, no diesel could come close in my heart.” This sentiment underscored a passion that transcended mere financial gain. As Dan Cupper, editor of Railroad History, the journal of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, aptly observed, Mr. Rowland arrived at a singular moment in railroad history.

“When steam locomotives had become irrelevant, passenger trains were on life support, and American railroads were free-falling into bankruptcy at a rate not seen since the Great Depression, Rowland came along to brashly champion all three,” Mr. Cupper stated. He further emphasized the unprecedented nature of Mr. Rowland’s efforts, noting that they came “from a person not employed by the railroad industry.”

Mr. Rowland’s personal life saw its share of transitions. His first marriage, to Doris Lakin, concluded in divorce. He found companionship again when he married Karen Bendix in 1998. He is survived by his wife, Karen Bendix; two children from his first marriage, Cathy Pattison and Joseph Rowland; and a grandson. He was preceded in death by another son, James.

In his final act of dedication to his beloved Chesapeake & Ohio No. 614, Mr. Rowland celebrated its successful sale in November 2024 to RJD America, a private rail preservation firm that plans to restore the locomotive to operation. In June, just weeks before his passing, the 614 was moved from its long-time home in Clifton Forge, Va., to the Strasburg Rail Road, where restoration work has since begun. Mr. Rowland was notably “along for the ride,” witnessing this critical step in his engine’s future.

Ross E. Rowland Jr. will be remembered not only as a successful Wall Street commodities trader but as a singular showman and an unwavering champion of American railroad history. His admirers frequently recalled him as the “archetypal hogger,” a term for a steam locomotive engineer, often pictured leaning out the cab window, clad in the classic regalia of a polka-dot cap, denim overalls, and leather gauntlets. His journey, from a boy captivated by trains to a titan who literally moved mountains for them, leaves an indelible mark on the landscape of rail preservation.

His life was a testament to the power of a deeply held passion, demonstrating that even against overwhelming odds and shifting tides, one individual’s conviction can ignite a nationwide enthusiasm. Ross Rowland’s legacy, woven into the fabric of American industrial heritage, will continue to echo in the thunderous rhythm of restored steam engines, a reminder of what one man’s dreams, coupled with a Wall Street fortune, could achieve.