The annals of early Christian history are illuminated by figures whose intellectual prowess and spiritual devotion shaped the very foundations of Western thought. Among these luminaries stands Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus, universally known as Saint Jerome, a towering priest, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian. His life, spanning from approximately 342–347 to 420 AD, was a relentless pursuit of scriptural understanding, a journey that profoundly influenced Christian doctrine, scholarship, and even the artistic imagination for centuries to come.

Jerome’s contributions extend far beyond the confines of his monastic cells; he was a dynamic force in the cosmopolitan centers of his time, particularly Rome, where his teachings on Christian moral life resonated deeply. His dedication to meticulous scholarship, combined with an unyielding spiritual fervor, equipped him to undertake tasks that would define the linguistic and theological landscape of the nascent Christian empire. It is through his tireless efforts that the complex tapestry of the Bible was woven into a singular, authoritative Latin text, forever altering the course of religious observance and study.

This in-depth exploration will delve into the multifaceted life and monumental achievements of Saint Jerome, examining the pivotal moments and key works that solidified his status as one of the most significant figures in ancient Latin Christianity. From his early education and dramatic conversion to his intricate relationships with influential women and groundbreaking translation projects, Jerome’s story is a testament to the enduring power of intellect married to unwavering faith.

1. Identity and Enduring Legacy

The Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Lutheran Church, and the Anglican Communion all recognize him as a saint, underscoring the widespread reverence for his intellectual and spiritual authority. Such universal acclaim testifies to the enduring impact of his work, particularly his unparalleled dedication to biblical scholarship. He is, to this day, venerated not just for his piety but for the sheer volume and quality of his scholarly output.

His legacy is also preserved in his status as the patron saint of translators, librarians, and encyclopedists, a fitting tribute to a man who dedicated his life to making sacred texts accessible and comprehensible. This designation highlights his pioneering efforts in translation and the meticulous organization of knowledge, making him a beacon for those who navigate and disseminate information. Jerome’s life truly exemplifies the power of focused intellectual and spiritual commitment to leave an indelible mark on civilization.

Read more about: Driving the Narrative: The Iconic Vehicles of Stranger Things and Their Unseen Influence

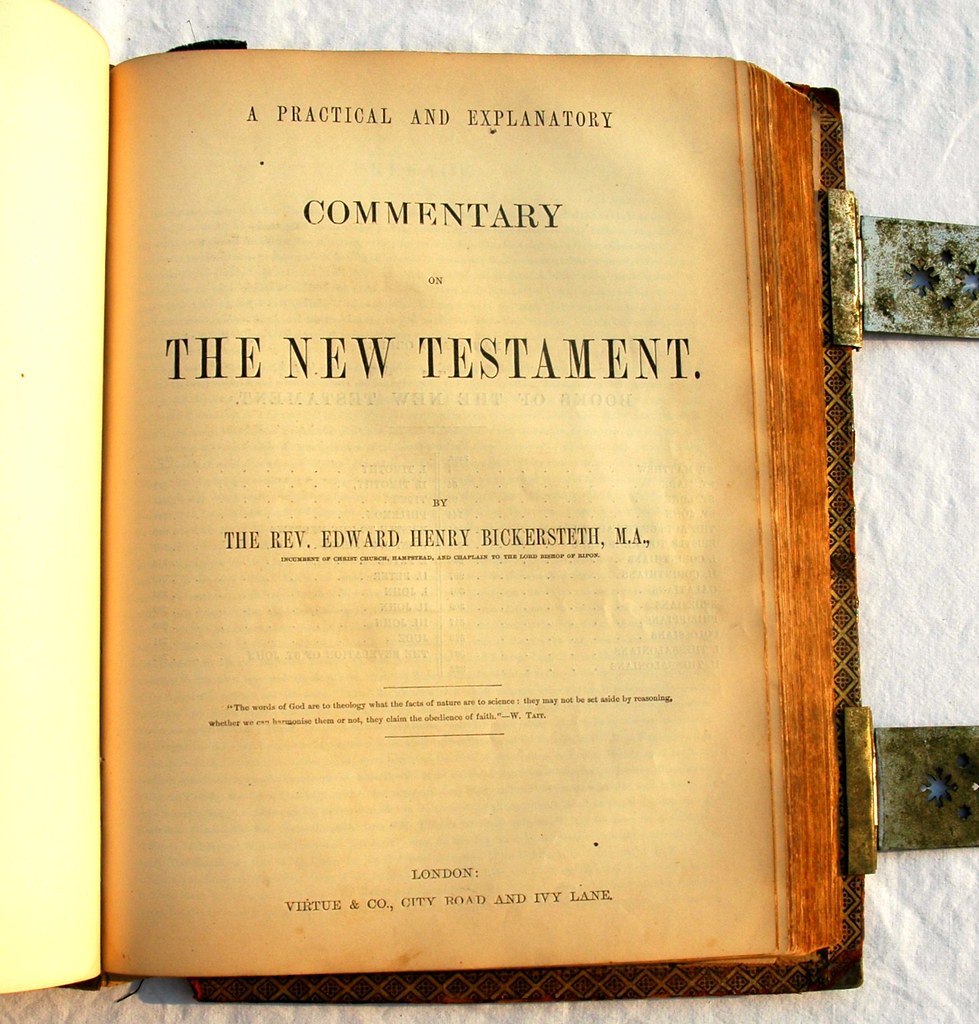

2. The Monumental Vulgate Translation

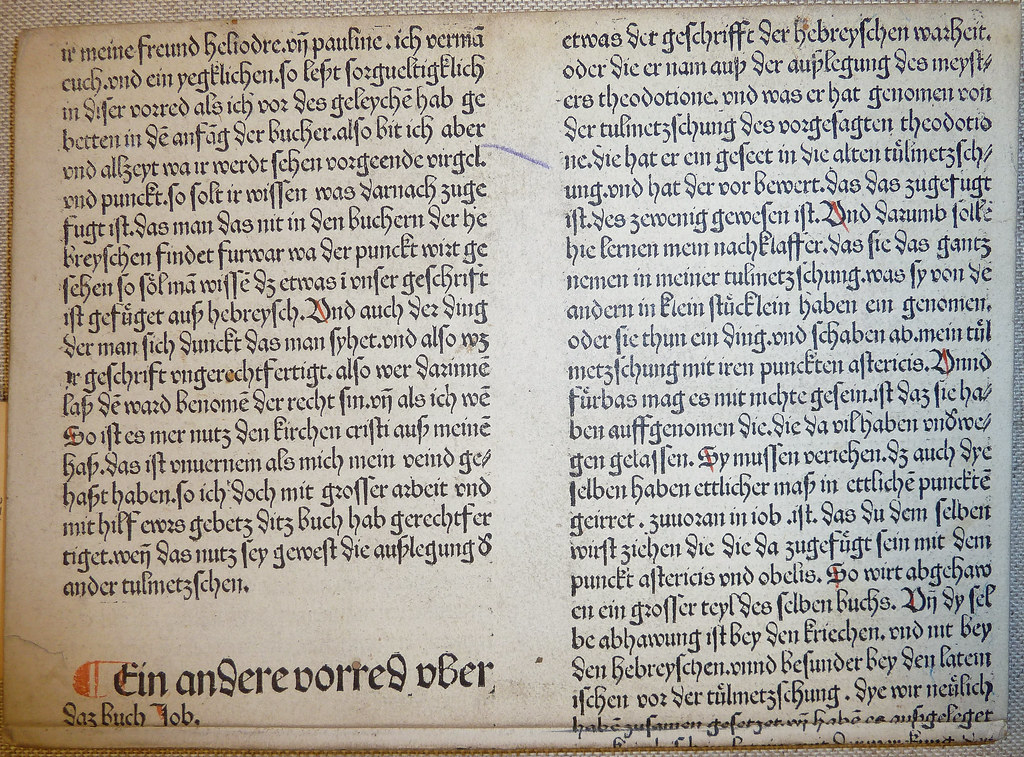

Jerome’s most celebrated achievement, and arguably his greatest gift to Western Christianity, is his translation of the Bible into Latin, a work that famously became known as the Vulgate. This monumental undertaking involved not merely a linguistic transfer but a profound act of theological interpretation and scholarly discernment. It was a project that consumed years of his life and revolutionized biblical study for over a millennium.

Prior to Jerome’s Vulgate, all Latin translations of the Old Testament relied on the Septuagint, the Greek version. Jerome, however, embarked on the audacious decision to translate the Old Testament directly from a Hebrew version, a choice that went against the counsel of many contemporaries, including Augustine, who viewed the Septuagint as inspired. This commitment to the “Hebraica veritas,” or Hebrew truth, demonstrated his profound conviction in seeking the original sources.

He began this extensive work in 382 by revising the existing Latin New Testament, the Vetus Latina, based on Greek manuscripts. By 390, he turned his attention to the Hebrew Bible, completing this colossal task by 405. The Vulgate eventually superseded all previous Latin translations and was later declared authoritative by the Council of Trent in 1546 for “public lectures, disputations, sermons, and expositions,” cementing its status as the official Latin Bible of the Catholic Church.

3. Early Life and Intellectual Awakening

Born Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus in Stridon sometime between 342 and 347 AD, Jerome was of Illyrian ancestry. His early life was marked by a significant move to Rome with his friend Bonosus of Sardica, where he immersed himself in rhetorical and philosophical studies. It was here, in the vibrant intellectual hub of the Roman Empire, that he received his foundational education and was exposed to the classical literary traditions that would later inform his extensive writings.

Under the tutelage of the renowned philologist Aelius Donatus, Jerome honed his linguistic skills, acquiring proficiency in Latin and at least some Koine Greek. While he may not have initially gained the deep familiarity with Greek literature that he later asserted, this period was crucial in shaping his intellectual rigor and laying the groundwork for his future scholarly pursuits. Rome provided him with the tools of rhetoric and critical analysis, skills he would employ throughout his life in defending Christian doctrine and translating sacred texts.

Yet, his student years in Rome were not without their internal conflicts. Jerome candidly admitted to engaging in “superficial escapades and ual experimentation,” experiencing profound guilt in their aftermath. To alleviate his conscience, he would visit the “sepulchers of the martyrs and the Apostles in the catacombs” on Sundays, experiences that vividly reminded him of the “terrors of Hell,” as he recounted, evoking lines from Virgil to describe the pervasive horror and silence of those subterranean crypts.

Read more about: Quincy Jones, the Master Orchestrator Whose Boundless Influence Reshaped Global Music and Entertainment, Dies at 91

4. Conversion and Ascetic Pursuits

Despite his initial apprehension towards Christianity, Saint Jerome underwent a significant conversion, leading him towards a life of fervent ascetic penance. This transformation marked a decisive turning point, redirecting his intellectual energies and personal discipline towards spiritual devotion. It set him on a path of profound self-denial and intense scriptural study, which would define the remainder of his life.

Following his conversion, Jerome sought the solitude of the desert of Chalcis, located southeast of Antioch, an area famously known as the “Syrian Thebaid” due to the multitude of hermits inhabiting it. During his time in this stark wilderness, he not only embraced a rigorous ascetic lifestyle but also dedicated himself to further scholarly endeavors. It was here that he made his first concerted attempt to learn Hebrew, guided by a converted Jew, a critical step towards his later biblical translation work.

His sojourn in the desert allowed him to deeply engage with the scriptures and engage with Jewish Christians in Antioch, even copying for himself a Hebrew Gospel, known today as the Gospel of the Hebrews. This period of intense spiritual discipline and linguistic acquisition was formative, preparing him intellectually and spiritually for the colossal task of translating the entire Bible. The desert, for Jerome, became a crucible where his scholarly mind was fused with his ascetic spirit, forging the remarkable individual he was to become.

5. Ministry and Influential Patronage in Rome

Upon returning to Rome, Jerome entered a new phase of his life, becoming a protégé of Pope Damasus I, who entrusted him with significant ecclesiastical duties. This period marked his re-entry into the bustling center of Christian power, where his scholarly talents were immediately put to use. His initial assignments focused on vital textual work, demonstrating the Pope’s recognition of Jerome’s unique abilities in linguistics and scriptural accuracy.

Among his principal tasks was the revision of the Vetus Latina Gospels, which he undertook using Greek manuscripts, aiming to correct inconsistencies and inaccuracies that had accumulated over time. Additionally, he updated the Psalter then in use in Rome, basing his revisions on the Septuagint. These early textual endeavors were critical precursors to his magnum opus, the Vulgate, showcasing his commitment to producing the most accurate and reliable Latin texts of the Christian scriptures.

However, Jerome’s time in Rome, though marked by significant achievements, was also fraught with contention. His unsparing criticism of the “secular clergy of Rome” and their supporters, coupled with the inclination of his female associates towards monastic life, generated considerable hostility. This mounting opposition eventually led to an inquiry by the Roman clergy into allegations of an “improper relationship with the widow Paula,” forcing him to depart Rome soon after the death of his patron, Pope Damasus I, in 384.

6. Championing Women’s Spiritual Lives

A distinctive aspect of Saint Jerome’s ministry was his profound engagement with, and advocacy for, the spiritual lives of women, particularly those in cosmopolitan centers like Rome. His teachings often centered on “how a woman devoted to Jesus should live her life,” a focus that emerged from his close relationships with “several prominent female ascetics” who belonged to “affluent senatorial families.” This unique patronage reflected a deep commitment to guiding women in their pursuit of devout lives.

Jerome was famously “surrounded by women and united with close ties,” an observation supported by the fact that “40% of his epistles were addressed to someone of the female .” His circle included notable figures such as the widows Lea, Marcella, and Paula, as well as Paula’s daughters, Blaesilla and Eustochium, all of whom were drawn to the monastic life as an alternative to the “indulgent lasciviousness in Rome.” He provided them with spiritual guidance, instructing them on vows of virginity, abstentions, and ascetic practices.

Despite his genuine efforts to guide these women, his influence was not without controversy. His “condemnation of Blaesilla’s hedonistic lifestyle” led her to embrace asceticism, which regrettably “affected her health and worsened her physical weakness to the point that she died just four months after starting to follow his instructions.” This tragic outcome provoked outrage among the Roman populace, who perceived Jerome as responsible for her premature death, further polarizing public opinion against him. His insistence that Blaesilla should not be mourned, deeming Paula’s grief “excessive,” was seen as “heartless,” exacerbating the criticisms he faced.

Having explored the foundational aspects of Saint Jerome’s life, from his initial intellectual pursuits and profound conversion to his transformative work on the Vulgate and controversial Roman ministry, we now turn our attention to the further intellectual and spiritual contributions that solidified his enduring legacy. This second section delves into the breadth of his scholarly works beyond translation, his historical endeavors, the unique insights offered by his extensive correspondence, and the intricate theological positions he championed, culminating in an examination of his profound reception and rich artistic portrayal through the ages.

Read more about: Gisele Bündchen’s Journey: Unpacking the Supermodel’s Life, Loves, and the Evolution Leading to Her Split from Tom Brady

7. Commentaries on Scripture

Following the completion of his monumental Vulgate, Saint Jerome dedicated the subsequent 15 years of his life, until his death, to producing an extensive collection of commentaries on Scripture. These works were not merely interpretative but often served to elucidate his meticulous translation choices, particularly his reliance on the original Hebrew text over existing, potentially ‘suspect’ translations. His commitment to scholarly rigor permeated these exegetical endeavors, ensuring that his deep understanding of the source languages informed his theological insights.

Jerome’s patristic commentaries frequently aligned closely with Jewish tradition, demonstrating an impressive engagement with contemporary Jewish scholarship. At the same time, he was not averse to engaging in allegorical and mystical subtleties, a style he adopted after the manner of figures like Philo and the Alexandrian school of interpretation. This blend of literal and allegorical approaches showcased his versatility as a theologian and his profound appreciation for the diverse layers of scriptural meaning.

A significant aspect of his commentary work was his emphasis on differentiating between the Hebrew Bible’s “Apocrypha” and the “Hebraica veritas” of the protocanonical books. In the prologues to his Vulgate, he explicitly described certain portions of books found in the Septuagint but not in the Hebrew as being non-canonical, categorizing them as apocryphal. While he notably mentioned Baruch in his Prologue to Jeremiah, noting it was neither read nor held among the Hebrews, he refrained from explicitly labeling it apocryphal or “not in the canon,” illustrating a nuanced discernment.

His firm stance on the biblical canon was further articulated in his Preface to the Books of Samuel and Kings, famously known as the Helmeted Preface. Here, he declared: “This preface to the Scriptures may serve as a ‘helmeted’ introduction to all the books which we turn from Hebrew into Latin, so that we may be assured that what is not found in our list must be placed amongst the Apocryphal writings. Wisdom, therefore, which generally bears the name of Solomon, and the book of Jesus, the Son of Sirach, and Judith, and Tobias, and the Shepherd are not in the canon. The first book of Maccabees I have found to be Hebrew, the second is Greek, as can be proved from the very style.”

Read more about: Hal Lindsey: Unpacking the Enduring Legacy of the ‘Late Great Planet Earth’ Author at 95

8. Historical and Hagiographic Writings

Beyond his monumental contributions to biblical translation and commentary, Jerome also distinguished himself as a significant historical writer. His most renowned historical work, the `Chronicon`, was a comprehensive translation, reworking, and continuation of the `Chronicon` of Eusebius. Composed in Constantinople around 380 AD, this text swiftly became an immensely influential resource within Latin Christendom, despite acknowledging that it was not without its factual errors.

Jerome’s engagement with history extended beyond standalone chronicles; he frequently integrated historical events into his other writings, employing them as illustrative examples and potent sources of argument. This approach underscored his belief in the practical utility of historical knowledge for theological and moral discourse. While he clearly participated in historical writing, he did not consider himself strictly bound by the conventional rules observed by historians of his era, and his output in this domain must be assessed with this perspective in mind.

Remarkably, Jerome’s hagiographic writings also contain a unique historical detail, perhaps the earliest account of the etiology, symptoms, and cure of severe vitamin A deficiency. This passage describes an individual: “From his thirty-first to his thirty-fifth year he had for food six ounces of barley bread, and vegetables slightly cooked without oil. But finding that his eyes were growing dim, and that his whole body was shrivelled with an eruption and a sort of stony roughness (impetigine et pumicea quad scabredine) he added oil to his former food, and up to the sixty-third year of his life followed this temperate course, tasting neither fruit nor pulse, nor anything whatsoever besides.” This precise medical observation, embedded within a spiritual biography, highlights the unexpected breadth of information preserved in his works.

9. Extensive Correspondence (Letters)

Saint Jerome’s letters, or epistles, represent an extraordinarily rich and diverse portion of his literary legacy, notable for both their thematic variety and the distinctive qualities of their style. These letters transcend mere personal communication, offering a vibrant tableau of his intellectual engagements, spiritual struggles, and the socio-religious landscape of his time. Whether he was meticulously discussing intricate problems of scholarship, offering reasoned advice on complex cases of conscience, extending comfort to the afflicted, or exchanging pleasantries with his friends, his epistolary output was both prolific and profound.

In these letters, Jerome did not shy away from controversy or critique. He famously scourged the vices and corruptions prevalent in his era, including ual immorality among the clergy, and passionately exhorted his readers towards an ascetic life and the renunciation of worldly distractions. Moreover, his correspondence frequently served as a platform for debating theological opponents, through which he presented a vivid and often unvarnished picture not only of his own sharp intellect and fervent spirit but also of the age itself and its peculiar characteristics.

A fascinating aspect of his letters is the absence of a distinct line between personal documents and those intended for wider publication. Consequently, his epistles often contain a blend of confidential messages and formal treatises that were clearly meant for a broader audience beyond the specific recipient. This practice led to their wide circulation and avid readership throughout the Christian empire, extending his influence far beyond the immediate circle of his correspondents.

Indeed, due to his extended period in Rome and his close interactions with wealthy families from the Roman upper class, Jerome was frequently commissioned by women who had embraced a vow of virginity to provide guidance on how to live their consecrated lives. As a direct result, a substantial portion of his life was dedicated to corresponding with these women, offering detailed instructions and counsel on specific abstentions, ascetic practices, and the overall spiritual conduct appropriate for their chosen path.

10. Eschatological Views

Jerome’s theological writings frequently delved into eschatology, offering forthright warnings against those who substituted “fake interpretations for the actual meaning of Scripture,” contending that such individuals belonged to the “synagogue of the Antichrist.” His conviction was starkly expressed in a letter to Pope Damasus I, where he asserted, “He that is not of Christ is of Antichrist.” This unwavering stance underscored his deep concern for doctrinal purity and the integrity of biblical understanding.

He believed that the “mystery of iniquity” foretold by Paul in 2 Thessalonians 2:7 was already actively at work in his own time, observing that “every one chatters about his views.” For Jerome, the Roman Empire functioned as the power restraining this mystery, and with its discernible decline, he foresaw the imminent removal of this crucial deterrent, signaling the approaching advent of the Antichrist. He urgently warned a noblewoman of Gaul: “He that letteth is taken out of the way, and yet we do not realize that Antichrist is near. Yes, Antichrist is near whom the Lord Jesus Christ ‘shall consume with the spirit of his mouth’.” He further lamented the widespread devastation wrought by various “savage tribes in countless numbers” across Gaul, including the Quadi, Vandals, Sarmatians, Alans, Gepids, Herules, Saxons, Burgundians, Allemanni, and Pannonians, viewing these tumultuous events as signs of the times.

His `Commentary on Daniel` was specifically composed to counteract the criticisms advanced by Porphyry, who controversially taught that the book of Daniel related entirely to the era of Antiochus IV Epiphanes and was authored by an unknown individual in the second century BC. In opposition to Porphyry’s interpretation, Jerome firmly identified Rome as the fourth kingdom described in chapters two and seven of Daniel. However, his view of chapters eight and eleven was more intricate, suggesting that chapter eight depicted the activities of Antiochus Epiphanes, understood as a “type” of a future antichrist, while 11:24 onwards applied primarily to a future antichrist but had been partially fulfilled by Antiochus.

Jerome advocated that the “little horn” of Daniel’s prophecies represented the Antichrist. He concurred with the traditional interpretation of Christian commentators, predicting that “at the end of the world, when the Roman Empire is to be destroyed, there shall be ten kings who will partition the Roman world amongst themselves. Then an insignificant eleventh king will arise, who will overcome three of the ten kings. … After they have been slain, the seven other kings also will bow their necks to the victor.” He clarified in his commentary that the Antichrist should not be perceived as “either the Devil or some demon, but rather, one of the human race, in whom Satan will wholly take up his residence in bodily form.” He also posited that the Antichrist would sit in God’s Temple not by rebuilding the Jewish Temple, but by making “himself out to be like God.”

Additionally, Jerome identified the four prophetic kingdoms symbolized in Daniel 2 as the Neo-Babylonian Empire, the Medes and Persians, Macedon, and Rome, interpreting the “stone cut out without hands” as “namely, the Lord and Savior.” He further refuted Porphyry’s application of the little horn of chapter seven to Antiochus, anticipating that Rome’s destruction at the world’s end would precede its partition among ten kingdoms before the appearance of the little horn. For Daniel 8:3, he believed Cyrus of Persia was the higher of the two horns of the Medo-Persian ram, and the he-goat represented Greece smiting Persia in Daniel 8:5.

Read more about: Mary, Mother of Jesus: Unpacking the Profound Reverence and Diverse Interpretations Across Global Faiths and Centuries

11. Soteriological Perspectives

In his theological discourse, Saint Jerome also engaged deeply with soteriology, the study of salvation. A notable aspect of his views was his fervent opposition to Pelagianism, a doctrine he actively wrote against approximately three years before his death. This opposition underscored his commitment to orthodox Christian teachings on grace, human will, and the nature of sin, placing him firmly in the camp of those who emphasized divine initiative in salvation.

Intriguingly, despite his general antagonism towards Origen, Jerome’s soteriology reveals a discernible influence from Origenism. While he diverged from Origen by teaching that the Devil and the unbelieving would face eternal punishment, he held a more nuanced view regarding Christian sinners. He believed that the punishment meted out to those who had once believed but subsequently sinned and fell away would be temporal in nature, rather than perpetual. This perspective suggested a purgative rather than eternally damning consequence for such believers.

This particular distinction in his understanding of post-mortem judgment has led some scholars, such as J.N.D. Kelly, to interpret that Ambrose, another prominent Church Father, may have held similar views concerning the judgment of Christians. Such shared or analogous positions among leading theologians of the era highlight complex intellectual exchanges and evolving doctrinal nuances within early Christianity. Although Augustine did not explicitly name Jerome, his treatise “On Faith and Works” offered a critique of the view that all Christians would ultimately be reunited to God, suggesting a broader debate around these soteriological questions.

12. Reception and Enduring Artistic Legacy

Saint Jerome’s profound intellectual and spiritual output ensured his significant reception throughout Christian history. He stands as the second-most voluminous writer in ancient Latin Christianity, surpassed only by Augustine of Hippo. His monumental contribution is formally recognized by the Catholic Church, which venerates him as the patron saint of translators, librarians, and encyclopedists – fitting titles for a scholar who dedicated his life to organizing and elucidating sacred knowledge.

The enduring authority of his translations is undeniable; the Vulgate, which incorporated his extensive work in translating biblical texts from Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, progressively superseded all preceding Latin versions of the Bible, known collectively as the Vetus Latina. Its importance was decisively cemented when the Council of Trent, in 1546, formally declared the Vulgate authoritative “in public lectures, disputations, sermons, and expositions,” establishing it as the standard Latin Bible for the Catholic Church for centuries.

Jerome’s life, characterized by an intense ascetic ideal, demonstrated a greater zeal for spiritual discipline than for abstract theological speculation. His commitment to asceticism saw him live as a hermit for four to five years in the Syrian desert and later for 34 years near Bethlehem. Nevertheless, his prolific writings consistently exhibit outstanding scholarship, and his extensive correspondence holds immense historical importance, providing invaluable insights into the intellectual, social, and spiritual currents of his time.

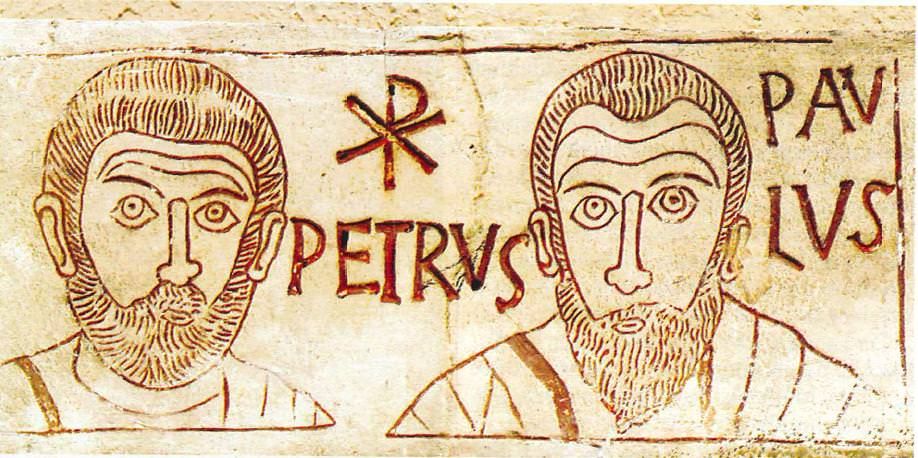

Beyond his textual legacy, Saint Jerome enjoys a rich and varied artistic tradition, making him one of the most frequently depicted saints. He is very often portrayed alongside a lion, a popular hagiographical motif derived from the belief that he once tamed a lion in the wilderness by healing its injured paw. The true origin of this captivating tale, however, is thought to stem either from the second-century Roman story of Androcles or from a confusion with the exploits of Saint Gerasimus, with “Geronimus” being a later Latin form of Jerome’s name. This charming narrative, a “figment” according to the thirteenth-century Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine, has nonetheless become an inseparable part of his iconography.

From the late Middle Ages onward, depictions of Jerome in broader settings became increasingly popular. Artists often showed him in his study, surrounded by books and the scholarly equipment befitting a man of letters, or in a stark, rocky desert, symbolizing his ascetic life. Sometimes, these elements were combined, with Jerome studying a book under the shelter of a rock-face or within a cave mouth. In these “study” depictions, he is often clean-shaven, well-dressed, and may even be accompanied by a cardinal’s hat, an anachronistic but honorary visual cue to his significance. These images often draw from the tradition of the evangelist portrait, granting Jerome the meticulous library and desk of a serious scholar. His symbolic lion, frequently rendered at a smaller scale, is typically positioned beside him in either setting.

Another significant artistic theme, particularly from the later 15th century in Italy, is “Jerome Penitent.” In these works, he is typically situated in the desert, clad in ragged clothes or even above the waist, his gaze intently fixed on a crucifix as he engages in self-mortification by beating himself with his fist or a rock. Georges de La Tour’s 17th-century French versions notably juxtapose his penitence with the vivid presence of his red cardinal hat. Furthermore, Jerome is often linked to the `vanitas` motif, a profound reflection on the meaninglessness of earthly life and the transient nature of all worldly goods and pursuits. Pieter Coecke van Aelst’s 16th-century “Saint Jerome in his study” exemplifies this, depicting the saint with a skull and an admonition pinned to the wall: “Cogita Mori” (“Think upon death”). Other reminders of the passage of time and the imminence of death, such as an image of the Last Judgment within his Bible, a burning candle, and an hourglass, frequently accompany these powerful visual narratives. His iconography also includes an owl, symbolizing wisdom and scholarship, along with writing materials and the trumpet of final judgment, all contributing to a multifaceted and enduring artistic representation of this towering figure in Christian history.

Read more about: Lights, Camera, Conflict: 15 Iconic Actors Who Refused to Film Scenes Together on Set

Saint Jerome’s tireless dedication to scholarship, his unyielding spiritual discipline, and his profound theological insights collectively shaped the course of Western Christianity in ways that continue to resonate. From the foundational text of the Vulgate to his nuanced commentaries, his rich correspondence, and his enduring image in art, he stands as a testament to the transformative power of intellect and faith in equal measure. His life remains an enduring source of inspiration and study, a beacon of rigorous scholarship and unwavering devotion that transcended the limitations of his age to leave an indelible mark on human civilization.