Let’s kick things off with a bang! You might have seen the name “Sami” pop up in headlines or social feeds, often linked to the glitzy world of celebrity families. But what if we told you there’s another “Sami” story, one far older, richer, and deeply rooted in the breathtaking landscapes of Northern Europe? We’re talking about the Sámi people – the Indigenous inhabitants of a region they call Sápmi, a vast territory stretching across Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia’s Kola Peninsula. Their journey isn’t just a transformation; it’s a testament to resilience, cultural richness, and an enduring spirit against centuries of challenges.

This isn’t your average history lesson; it’s an intimate look into a vibrant culture that has navigated everything from ancient migrations to modern political struggles. We’ll explore how their identity has been shaped, challenged, and ultimately strengthened over millennia. From their unique languages to their profound connection with the land, the Sámi story is a powerful narrative of survival, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to preserving their heritage in a rapidly changing world.

So, buckle up! We’re about to dive deep into the fascinating world of the Sámi, uncovering the layers of their past and present, and celebrating the incredible transformations that define this remarkable Indigenous community. Forget what you think you know about “Lapland” – we’re going straight to the source, guided by the voices and experiences of the Sámi themselves.

1. **The Sámi Identity: Beyond Laplanders and Lapps**When we talk about the Sámi, it’s crucial to start with identity – an identity that has, for too long, been misrepresented and burdened by external labels. Historically, in English, the Sámi were often referred to as “Lapps” or “Laplanders.” While these terms might still linger in some older texts or casual conversation, it’s important to understand that they are considered offensive by the Sámi themselves. They prefer their own endonym, “Sámi,” a powerful statement of self-determination and cultural respect. This shift from externally imposed names to their chosen identity is a crucial part of their ongoing transformation, emphasizing autonomy and cultural pride.

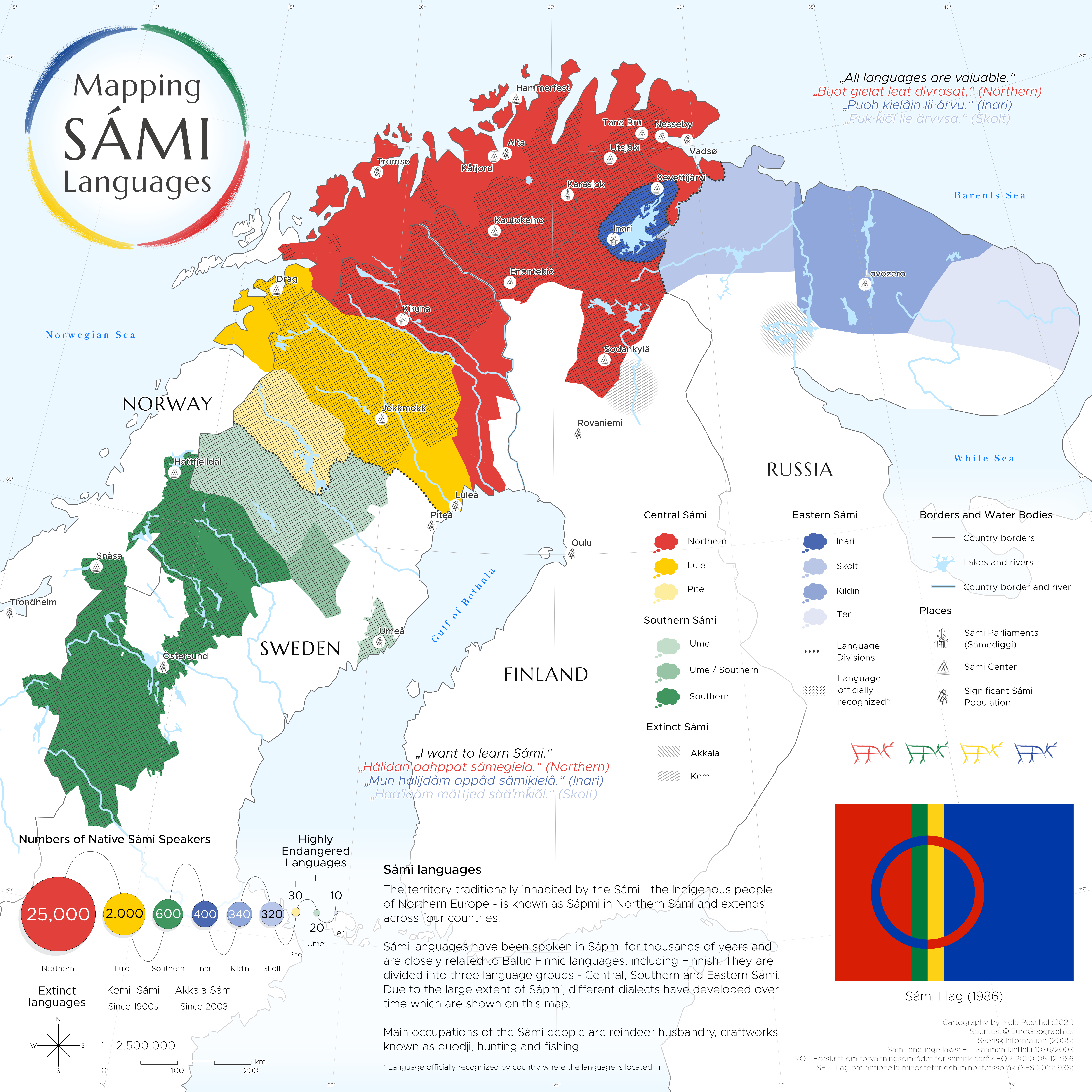

The Sámi are the traditionally Sámi-speaking indigenous people inhabiting the region of Sápmi. This vast and ecologically diverse area today encompasses large northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and extends into the Kola Peninsula in Russia. It’s a land rich in history and natural beauty, and for the Sámi, it’s not just a place on a map; it’s the heart of their culture, their livelihoods, and their spiritual connection to the world. Understanding Sápmi is key to understanding the Sámi.

Their traditional languages, the Sámi languages, are not just dialects but a distinct branch of the Uralic language family. These languages are a vital component of Sámi identity, carrying generations of knowledge, stories, and a unique way of understanding the world. Preserving and promoting these languages is a continuous effort, especially after periods where their use was suppressed, highlighting the importance of linguistic heritage in cultural survival. The collective effort by Sámi institutions – including parliaments, radio and TV stations, and theatres – to consistently use “Sámi” when addressing both their own people and outsiders, even in other languages like Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, or English, powerfully asserts their preferred terminology and reinforces their identity on a global stage. In Norwegian and Swedish, they are known by the localized form “same” (plural “samer”), showing a movement towards respecting their self-identification within Nordic countries.

2. **Rooted in Tradition: The Diverse Sámi Livelihoods**The Sámi people have never been monolithic in their way of life; instead, their traditional livelihoods showcase incredible adaptation to the Arctic environment. For centuries, they pursued a diverse range of activities, each intimately connected to the land and its resources. Coastal fishing was a cornerstone for many, especially those living along the extensive Northern European coastline, providing sustenance and a means of trade. Fur trapping, too, played a significant role, utilizing the rich wildlife of Sápmi, while sheep herding offered another vital source of food and materials. These practices weren’t just about survival; they were deeply interwoven with their cultural fabric, shaping community structures and knowledge systems.

However, among these diverse livelihoods, one stands out as arguably the most iconic and globally recognized: semi-nomadic reindeer herding. This practice, often romanticized by outsiders, is a complex and deeply traditional way of life that provides the Sámi with meat, fur, and transportation. It’s a testament to their profound connection with nature and their ability to thrive in challenging Arctic conditions. While only about 10% of the Sámi population was connected to reindeer herding as of 2007, with around 2,800 actively involved full-time in Norway, its cultural significance extends far beyond these numbers, symbolizing Sámi heritage and independence.

The importance of reindeer herding is so profound that in some regions of the Nordic countries, it is legally reserved exclusively for the Sámi. This isn’t just about economic protection; it’s a recognition of the deep traditional, environmental, cultural, and political reasons that tie the Sámi to this unique practice. This legal protection acknowledges the indigenous rights to maintain a way of life that has sustained their people for generations, ensuring that this vital aspect of their cultural identity can continue to flourish against modern pressures. It also underscores the importance of land and migratory routes, which become central in many contemporary issues facing the Sámi, as we’ll explore later.

3. **Unpacking the Names: Etymologies of Sámi and Finn**Have you ever wondered about the stories behind names? For the Sámi, the origins of the words used to describe them are as rich and complex as their history. Let’s start with “Sámi” itself. Speakers of Northern Sámi refer to themselves as Sámit (the Sámis) or Sápmelaš (of Sámi kin), with the word Sápmi inflected into various grammatical forms. The consensus among specialists around 2014 was that the word Sámi was borrowed from the Proto-Baltic word *žēmē, meaning ‘land’—a fascinating link to a deep linguistic past, cognate with Slavic “zemlja” (земля) which shares the same meaning. This etymology grounds their very name in the concept of land, reinforcing their intrinsic connection to their territory.

This linguistic journey doesn’t stop there. The word Sámi has at least one cognate word in Finnish, tracing back to the same Proto-Baltic root. *žēmē was also borrowed into Proto-Finnic as *šämä, eventually becoming modern Finnish “Häme” (the region of Tavastia). Even the Finnish word for Finland, “Suomi,” is thought to derive ultimately from Proto-Baltic *žēmē, though the precise etymological path is a subject of scholarly debate, often involving intricate processes of borrowing and reborrowing between Proto-Germanic, Proto-Baltic, and Proto-Finnic languages. This intricate web of linguistic connections highlights the deep historical interactions and shared roots within the broader Fennoscandian region, showcasing a complex cultural tapestry.

Moving to another historical term, “Finn,” it’s equally insightful. The first probable historical mention of the Sámi, naming them Fenni, dates back to Tacitus around AD 98. Variants like “Finn” or “Fenni” were widely used in ancient Roman and Greek works, and later by Norse speakers (and their proto-Norse ancestors) to refer to the Sámi, as seen in Icelandic Eddas and Norse sagas. The etymology, while somewhat uncertain, generally points to a relation with Old Norse “finna” (from Proto-Germanic *finþanan, meaning ‘to find’). The logic? The Sámi, as hunter-gatherers, “found” their food, rather than growing it – a simple yet powerful description of their traditional subsistence. This explanation has largely superseded older ideas linking the word to “fen” or marshland, grounding the name in their active engagement with their environment.

4. **The Controversial Legacy of “Lapp”: Understanding a Derogatory Term**While “Sámi” is the preferred and respectful term today, history often throws uncomfortable shadows. The word “Lapp” is one such shadow, and understanding its origins and why it’s considered derogatory is a crucial part of appreciating the Sámi struggle for self-definition. The term “Lapp” can be traced back to Old Swedish “lapper” and Icelandic “lappir” (plural), possibly of Finnish origin, with “Lappi” meaning “Lapland” (perhaps “wilderness in the north”), though its original meaning remains unknown. It’s a word whose history is murky, but its impact is clear.

The term’s popularity as standard terminology for the Sámi was significantly cemented by Johannes Schefferus’s influential work, “Lapponia,” published in 1673. Before this, even Saxo Grammaticus in the 12th century referred to ‘the two Lappias’ but still called the Sámi “(Skrid-)Finns,” never explicitly connecting them. This historical progression highlights how external scholarship and administrative practices often shaped perceptions and terminology, sometimes to the detriment of the indigenous people being described.

Today, while variants of “Lapp” are still used in many major European languages (English: Lapps; German, Dutch: Lappen; French: Lapons, etc.), they are widely considered derogatory by many Sámi. However, it’s worth noting that some accept “Lappland” as a geographical term. The nuanced situation extends to place names: “Lapp” is common in place names in Finland and Sweden (e.g., Lappi, Lappeenranta in Finland), but exceedingly rare in Norway where “Finn” is more common. In Finland, the distinction is also evolving, with “saamelainen” now the most commonly used word, especially in official contexts, reflecting a conscious move towards respectful and accurate terminology. Understanding this terminological shift is not just an academic exercise; it’s a recognition of the Sámi people’s fight for respect and dignity.

5. **Journey Through Time: The Ancient Origins of the Sámi People**To truly grasp the Sámi transformation, we must travel back millennia to their ancient roots. The western Uralic languages, to which Sámi languages belong, are believed to have spread from an original Proto-Uralic homeland along the Volga, Europe’s longest river. These early Uralic peoples began their northwestward migration in the second and third quarters of the 2nd millennium BC, utilizing ancient river routes across what is now northern Russia. It’s a story of movement, adaptation, and the gradual shaping of distinct cultural groups.

Some of these migrating groups settled in the regions between Karelia, Ladoga, and Lake Ilmen, while others ventured further east and southeast. It was the groups who ended up in the Finnish Lakeland around 1600 to 1500 BC who are believed to have later “became” the Sámi. This suggests a long, complex process of ethno-genesis, with the Sámi people arriving in their current homeland sometime during the Bronze Age or early Iron Age. This deep historical presence underscores their status as Indigenous people, having inhabited Sápmi for thousands of years.

The development of the Sámi language itself is a journey. It first emerged on the southern side of Lake Onega and Lake Ladoga, gradually spreading northward. As its speakers expanded into the area of modern-day Finland, they encountered and absorbed elements from smaller, now-extinct ancient languages, known as Paleo-Laplandic languages, leaving behind a “Pre-Finnic substrate” in the evolving Sámi language. This process of linguistic interaction and segmentation into dialects as the language spread further highlights the dynamic nature of cultural formation. The geographical distribution of the Sámi, from the coast of Finnmark to the Kola Peninsula in the Bronze Age, also coincides with the arrival of the Siberian genome to Estonia and Finland, potentially linked to the introduction of Finno-Ugric languages in the region, painting a vivid picture of ancient movements and cultural exchange.

6. **A Complex Coexistence: Sámi and Scandinavians Through History**The relationship between the Sámi and their Scandinavian neighbors, the dominant peoples of Norway and Sweden, is a tapestry woven with threads of independence, interaction, and, eventually, conflict. For centuries, following the independent migrations of Germanic-speaking peoples to Southern Scandinavia and the Sámi to the north, contact was relatively limited. The Sámi largely dwelled in the inland of northern Fennoscandia, while Scandinavians settled southern Scandinavia and gradually colonized the Norwegian coast. This initial spatial and economic separation allowed for distinct cultural developments with minimal interference.

However, this relative autonomy began to shift dramatically from the 18th, and especially the 19th, century. The governments of Norway and Sweden started to assert sovereignty more aggressively in the north. This marked a profound turning point, leading to the implementation of “Scandinavization policies.” These policies were not about coexistence; they were explicitly aimed at forced assimilation, seeking to integrate the Sámi into the dominant Scandinavian cultures, often at the expense of their own.

Before this era of forced assimilation, Norwegian and Swedish authorities had mostly overlooked the Sámi. Norwegians moving north prior to the 19th century were primarily interested in coastal fisheries for export, showing little concern for the harsh, non-arable inland where reindeer-herding Sámi lived self-sufficiently. But from the 19th century, this attitude hardened. The Sámi were increasingly seen as “backward” and “primitive,” in need of being “civilized.” This led to the imposition of Scandinavian languages as the only valid languages and effectively banned Sámi language and culture in many contexts, particularly within schools, laying the groundwork for a long and painful period of cultural suppression that would shape generations.

7. **Echoes of the Past: Uncovering Sámi Presence in Southern Regions**For many years, the historical reach of Sámi settlement, particularly how far south they extended, was a subject of considerable debate among historians and archaeologists. A foundational, yet contested, hypothesis emerged from Norwegian historian Yngvar Nielsen in 1889. Commissioned by the Norwegian government to address Sámi land rights, Nielsen concluded that the Sámi had not lived further south than Lierne Municipality in Trøndelag county until around 1500, suggesting a later southward movement to areas like Lake Femund by the 18th century. This perspective, though still held by some, has increasingly been challenged by new scholarship and compelling archaeological evidence in the 21st century, opening up a broader understanding of Sámi historical geography.

Recent archaeological finds are painting a much more expansive picture of Sámi historical presence, indicating a significant presence in southern Norway during the Middle Ages, and even in southern Sweden. Discoveries in places like Lesja Municipality, Vang Municipality, Valdres, and Hol and Ål Municipalities in Hallingdal, all point to a Sámi past that stretched considerably further south than previously acknowledged. These finds are compelling proponents of Sámi interpretations, suggesting that mountainous areas of southern Norway in the Middle Ages likely hosted a mixed population of Norse and Sámi peoples, highlighting a more integrated and complex historical landscape than once thought.

The re-evaluation extends to Finland as well. A 2022 study revealed that Sámi habitation was found across the entirety of continental Finland at least until the 14th century. Toponyms of Sámi origin are surprisingly common even in the southernmost provinces of Finland Proper and Uusimaa, with suggested Sámi etymologies for names like Aurajoki and Nuuksio. Historically, the Sámi coexisted with Finns and Swedes, primarily engaging in fishing, hunting, gathering, and fur trapping, rather than significant agriculture. However, the complete colonization of these southern Finnish provinces by Finns and Swedes ultimately led to the assimilation and disappearance of a distinct Sámi population by the 14th century, leaving behind linguistic traces as enduring echoes of their past presence.

8. **The Black Death’s Unforeseen Impact: Reshaping Sámi and Norwegian Lives**The bubonic plague, arriving in Northern Norway in 1349, dramatically altered the relationship between the Sámi and Norwegians. Until this catastrophe, these groups occupied separate economic niches, maintaining relatively little contact. The Sámi thrived on reindeer hunting and fishing, well-adapted to their environment.

Norwegians, concentrated along coastlines, were deeply integrated into European trade routes. This connection, while economically beneficial, facilitated the plague’s spread, causing Norwegians to die at a far higher rate than Sámi in the interior. Norway suffered catastrophic population losses, with up to 76 percent of farms abandoned in some northern parishes.

The Sámi, whose diet consisted of fish and reindeer rather than imported grains, and who lived in more detached communities, were largely spared this devastation. This differential impact led to a significant socioeconomic divergence, fundamentally reshaping the region’s demographic and cultural landscape.

9. **Diverging Paths: The Rise of Sea Sámi and Mountain Sámi**The Black Death’s aftermath sparked profound socioeconomic change within Sámi communities. With Norwegian populations decimated and land vacant, local authorities incentivized Sámi settlement on abandoned farms. This marked a turning point, creating a distinct economic division within the Sámi people.

This era saw the emergence of the “Sea Sámi” (sjøsamene), who embraced extensive coastal fishing, often combining it with farming and trapping. Archaeological evidence shows Sámi historically lived along the coast and further south, engaging in diverse work. The productive fishing grounds off Northern Norway became a vital income source.

Meanwhile, a minority, the “Mountain Sámi” (fjellsamene), continued hunting wild reindeer. Around 1500, they began domesticating these animals, becoming the iconic semi-nomadic reindeer herders. The settled Sea Sámi eventually became more numerous, but the cultural significance of Mountain Sámi reindeer herding remains immense.

10. **The Wisdom of the Waters: Traditional Sámi Fishing Practices**Traditional Sámi fishing practices exemplify a profound connection to the environment and generations of accumulated wisdom. Unlike modern commercial operations, Sámi fishing was a local, small-scale endeavor, tied to intimate knowledge of the landscape. They engaged with the sea, respecting its rhythms and secrets.

Fishermen utilized common grounds but also cherished personal, secret spots. Navigation relied not on GPS, but on incredible topographical memory. They named locations based on coastal landmarks and seafloor intricacies, embedding knowledge into their language. This allowed them to predict tides and fish seasonally, maximizing their catches.

This indigenous knowledge was a living legacy, passed down from elder to youth. As one community anecdote highlights, successful fjord fishing depends on “knowledge passed on from the earlier generations.” Sadly, this invaluable heritage has declined due to colonialism, the replacement of traditional place names, and modern fishing techniques.

11. **The Long Shadow of Assimilation: Scandinavization Policies and Cultural Suppression**Despite Sámi adaptation to the Arctic, the 19th century brought aggressive “Scandinavization” policies aimed at forced assimilation. Initially, Norwegian and Swedish authorities largely ignored the Sámi. However, they soon began to view Sámi as “backward,” needing “civilization.”

This led to the imposition of Scandinavian languages as the only valid ones, effectively banning Sámi language and culture in schools and other contexts. The introduction of compulsory schooling in Norway (1889) intensified this pressure, disconnecting Sámi children from their traditions. On Swedish and Finnish sides, Sámi language was also suppressed, further marginalizing their cultural and economic status.

The period from 1900-1940 saw intensified assimilation. In Finnmark, land acquisition required Norwegian language proof and names. Troubling race-segregation movements, like Sweden’s biological institute, dehumanized the Sámi, collecting “research material” from living people and graves, sowing deep internal divisions.

12. **Scorched Earth, Displaced Lives: War and Its Impact on Sámi Communities**Beyond assimilation pressures, the Sámi endured immense devastation during World War II, particularly from the German army’s 1944–45 “scorched earth” policy. This brutal tactic systematically destroyed all houses and visible traces of Sámi culture across northern Finland and Norway, wiping out their physical heritage.

Forced assimilation policies themselves caused significant Sámi dislocation throughout the 1920s, exacerbating divisions that still cause internal ethnic conflict today. Another documented displacement occurred between 1919 and 1920 in Norway and Sweden, reflecting a persistent pattern of uprooting Indigenous communities.

The impacts of these historical traumas lingered. After WWII, while overt pressure eased, the legacy remained. A 1970s Norwegian law limiting Sámi house sizes subtly controlled their lives. These events underscore the profound and lasting scars left by external forces on Sámi society.

13. **A Modern Battleground: Natural Resource Extraction and Sámi Land**Today, the fight for Sámi rights centers on protecting traditional lands from natural resource extraction. Sápmi is rich in precious metals, oil, and gas, making it a target for industrial development. However, mining and prospecting frequently clash with vital Sámi livelihoods, particularly reindeer grazing and calving areas.

Many active mining locations ironically sit within ancient Sámi spaces, some designated ecologically protected areas. The Sámi Parliament vehemently opposes these projects, demanding resource exploration directly benefit local communities. Proposed mines on Sámi lands directly threaten their ability to maintain traditional livelihoods.

This struggle is global. In Kallak, activists protested a UK mining company’s drilling in crucial reindeer winter grazing lands. Sweden’s low mineral taxes incentivize exploration at Sámi expense, prompting calls for ILO Convention No. 169 to grant land rights. Russia’s Kola Peninsula faces destruction from mining, oil/gas exploration, pipelines, and power lines encroaching on habitats and sacred sites. Northern Finland’s destructive logging also threatens lichen supplies vital for reindeer.

14. **Asserting Sovereignty: Sámi Land and Water Rights in the Modern Era**The struggle for Sámi land and water rights is an unwavering testament to their spirit and a focal point of modern activism. The controversial Alta hydroelectric power station in northern Norway (1979) rallied the Sámi movement, bringing Indigenous rights onto the political agenda. This highlighted environmental concerns and fundamental Sámi self-determination.

Today, battles continue. Sweden allowed the world’s largest onshore wind farm in Piteå, impacting Eastern Kikkejaure village’s winter reindeer pastures. This massive project, with over 1,000 turbines, makes grazing impossible, drawing international criticism for violating Sámi land rights. Some Norwegian Sámi politicians advocate for a Sámi Parliament veto on mining projects.

Even military activities intrude. Government authorities and NATO have established bombing-practice ranges in Sámi areas of northern Norway and Sweden. These regions have served as vital reindeer calving and summer grounds, and as sacred sites, for thousands of years.

In a landmark October 2024 victory, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights ruled Finland had violated Sámi Indigenous people’s rights to their land and culture, particularly regarding mining encroachment, emphasizing cultural rights over conventional property definitions – a significant step for Indigenous land tenure.

15. **Beyond Survival: Cultural Preservation, Repatriation, and the Fight Against Discrimination**The Sámi people are actively reclaiming, preserving, and transforming their cultural narrative amid persistent threats and historical injustices. The 1986 Chernobyl disaster, which poisoned Arctic ecosystems and forced the culling of 73,000 reindeer, serves as a stark reminder of their environmental vulnerabilities, impacting a way of life intrinsically linked to nature.

Cultural exploitation through tourism is also a challenge. In Finland, the industry commodifies Sámi culture, with non-Sámi performers and crude handicraft reproductions. “Crossing the Arctic Circle” is marketed as “authentic” Sámi, despite having no spiritual significance – an insulting display of exploitation.

However, a powerful movement for recognition and restitution is underway. Since the late 1990s, Sámi have campaigned for repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains (collected for “racial biology”). Repatriations continue, including skulls of 1852 uprising leaders and numerous others. International bodies criticize past assimilation policies, leading to truth commissions and formal apologies, while activists push for language rights, ensuring Sámi heritage is preserved and empowered.

From ancient routes to modern battlegrounds, the Sámi journey is a breathtaking saga of adaptation, resilience, and unwavering spirit. We’ve seen their identity powerfully reaffirmed, their diverse livelihoods speaking to an intimate connection with Sápmi. The shadows of assimilation and historical injustices are slowly yielding to the bright light of self-determination, driven by activism and global recognition of Indigenous rights. The Sámi story isn’t just about survival; it’s a vibrant, ongoing testament to cultural preservation, community strength, and the transformative impact of demanding respect for a heritage that has shaped Northern Europe for millennia. It reminds us to listen, learn, and celebrate the incredible transformations that define this remarkable Indigenous community, for all of us.