The promise of self-driving cars has captivated imaginations for years, painting a vivid picture of a future where commutes are effortless, traffic jams a distant memory, and road accidents virtually non-existent. Advanced driver assistance systems, like Tesla’s Autopilot or Volvo’s Pilot Assist, were introduced with the genuine hope of significantly reducing crashes by taking over routine driving tasks such as maintaining lane position and adjusting speed based on surrounding traffic. The underlying assumption was simple yet powerful: these technological aids would empower drivers to make fewer mistakes, thereby enhancing overall road safety and potentially saving thousands of lives annually, a truly transformative vision for our transportation landscape.

However, the reality emerging from recent studies tells a more nuanced and, frankly, concerning story. Instead of consistently making us safer, these systems are, in many instances, leading to an unexpected rise in driver distraction and, alarmingly, an increased risk of crashes. The very technology designed to assist us is, for some, fostering a dangerous false sense of security, actively encouraging drivers to mentally disengage from their primary and undeniable responsibility: driving. This isn’t solely about what the car’s software can achieve; it’s crucially about how we, as human operators, interact with these sophisticated tools and the critical psychological shifts they inadvertently induce behind the wheel.

It’s time to pull back the curtain on the most common missteps and pervasive misconceptions that drivers unknowingly adopt when using partial automation features. Understanding these pitfalls isn’t about shunning innovation or fearing progress; it’s about embracing it intelligently, safely, and with a clear recognition of its current, often significant, limitations. By identifying precisely where human-machine interaction tends to go wrong, we can recalibrate our approach, empowering ourselves to harness the true, transformative potential of these technologies without falling prey to their unintended and often perilous consequences. Let’s delve into these critical mistakes and learn how to navigate the evolving landscape of semi-autonomous driving with heightened awareness and unwavering responsibility.

1. **Over-reliance Leading to Increased Distraction**

When advanced automation features were first rolled out, the expectation was that they would reduce driver workload and make roads safer. The logic was simple: if cars handled mundane tasks, drivers would be less stressed and more attentive to critical situations. Yet, recent studies from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) show a surprising counter-narrative. Drivers using systems like Tesla’s Autopilot or Volvo’s Pilot Assist are becoming distracted more frequently than when driving unassisted, sometimes up to 30% more often.

This data suggests that instead of freeing up mental bandwidth for heightened vigilance, these systems inadvertently lull drivers into a dangerous false sense of security. Drivers begin to trust the technology implicitly, shifting their focus away from the road, traffic, and surroundings. This directly contradicts safe driving principles, where constant, active attention remains paramount. The convenience of partial automation is often misinterpreted as an invitation to disengage, fundamentally altering driver behavior in ways that compromise safety.

This increased distraction manifests in various forms. While the car maintains its lane or adjusts speed, drivers might check phones, engage in conversations, eat meals, or perform other non-driving tasks. All this occurs under the mistaken belief that the vehicle has everything under control. As Joel Feldman of EndDD.org explains, “It’s easy to think that if the car can drive itself, we can let our guard down—but that’s a dangerous misconception.” This creates a perilous gap between the technology’s actual capabilities and the driver’s optimistic perception. The car assists, but it is not driving for you in a fully autonomous sense. This blurred distinction leads to moments of inattention with severe consequences.

Read more about: Beyond the Blink: How a Ford Camera Glitch Uncovers Systemic Engineering Failures and the Lingering Shadows of Automotive Design Mistakes

2. **Developing “Cheating” Behaviors to Bypass Safety Warnings**

One of the most alarming findings in partial automation adoption is how quickly drivers learn to “cheat” these sophisticated systems. Manufacturers integrate attention warnings, requiring periodic steering wheel nudges or eye-tracking, specifically to keep drivers engaged. However, many drivers, particularly those with experience, discover methods to satisfy these warnings without genuinely paying active attention to the road.

This isn’t necessarily malicious; it’s often a slippery slope where initial trust morphs into a desire for ultimate convenience. This leads to behavioral shortcuts. A slight, almost imperceptible nudge to the steering wheel, just enough to register as driver presence, becomes a habit. This allows the driver to trick the system into believing they are attentive, while their mind and eyes are elsewhere, perhaps on a smartphone or another in-car distraction.

The profound consequence of “gaming” the system is a significant increase in risk. When a driver actively circumvents safety measures, they override a critical layer of protection. This dramatically reduces their ability to react swiftly if automation encounters a situation it cannot handle. It transforms a helpful feature into a source of grave danger. Drivers must understand these warnings are not obstacles, but essential safeguards bridging the gap between partial automation and human responsibility.

3. **Engaging in Multitasking While Automation Is Active**

The appeal of advanced driver assistance features often includes a more relaxed commute, freeing up mental space previously occupied by constant driving demands. Unfortunately, for many drivers, this perceived freedom is interpreted as an opportunity to multitask. They transform the car cabin into a mobile office, dining room, or entertainment lounge. Drivers are increasingly engaging in non-driving related activities, like checking emails, scrolling social media, eating, or watching videos, while partial automation is active.

This behavior directly contradicts the fundamental principle that even with technological assistance, the human driver remains the ultimate backup. They are solely responsible for the vehicle’s safe operation. While the car manages lane keeping or speed, it is not equipped to handle every conceivable scenario, especially unpredictable “edge cases” or sudden events. When a driver is deeply engrossed in another activity, their critical reaction time is severely compromised. This completely negates any safety benefits the automation might offer, turning potential advantages into serious liabilities.

The human brain is not truly designed for effective multitasking, particularly when one task involves monitoring a complex, dynamic, and hazardous environment like a roadway. Even a momentary glance away for a text message can lead to several seconds of “blind driving” at highway speeds, covering significant distances. With partial automation, this tendency to multitask is dangerously amplified by the perceived reduction in immediate driving demands. This creates a false and treacherous illusion that one can safely divide attention between the critical task of driving and other, less urgent activities.

Read more about: Reclaiming the Road: Why Stick Shift Cars Are Roaring Back into Style for Modern Drivers and Enthusiasts

4. **Misunderstanding System Limitations: Assuming Full Capability**

A pervasive and dangerous mistake drivers make is failing to fully comprehend the inherent limitations of self-driving features. Marketing language like “Full Self-Driving Beta,” while perhaps conveying advanced capabilities, can be profoundly misleading. It inadvertently fosters a belief that the vehicle is capable of operating completely autonomously in all situations. This misconception leads drivers to prematurely assume the car can handle every traffic scenario, road condition, or complex anomaly. In reality, these systems are often only rated for specific operational domains, requiring human oversight outside those parameters.

Understanding your system means knowing precisely what it can and cannot do. A Level 2 or Level 3 autonomous system requires the driver to remain attentive and continuously ready to intervene immediately. It is not a “set it and forget it” solution. Drivers who don’t thoroughly read their vehicle’s manual or truly grasp the explicit boundaries of the technology operate under a fundamental misunderstanding. This actively puts themselves and others at immense risk. They might mistakenly expect the car to autonomously navigate complex construction zones or erratic human drivers, capabilities current partial automation systems often cannot manage without human input.

This significant gap between driver expectation and technological reality can have severe consequences. When the car encounters a situation beyond its designated operational domain, it may disengage without sufficient warning or act unpredictably, absolutely requiring immediate human intervention. A driver who has incorrectly assumed full autonomy will be caught off guard, potentially too slow to react, or even unsure of how to take control effectively. Drivers must treat these features as advanced aids that reduce workload, not as complete substitutes for their own judgment, vigilance, and constant readiness to assume full command.

5. **Becoming Complacent Over Time, Leading to Higher Risk Behaviors**

Human nature dictates that familiarity with complex technologies can breed a dangerous sense of complacency. This is acutely evident in the long-term use of advanced driver assistance systems. What typically starts as cautious exploration and careful engagement can gradually, almost imperceptibly, devolve into an over-reliance that encourages higher-risk behaviors. As drivers become more accustomed to their vehicle’s automation, initial wariness wears off, replaced by a deep-seated trust that borders on unquestioning dependence, eroding active participation.

This increasing complacency means drivers are significantly less likely to actively monitor the road and the system’s performance. The intense mental effort required for safe driving, which remains substantial even with assistance, slowly diminishes. This reduced mental engagement directly increases the likelihood of delayed reactions or entirely missed cues when the system requires human intervention. Drivers might rationalize their diminished attention by thinking, “The car has always handled this,” or “It’s never failed before,” dangerously ignoring the inherent variability and unpredictability of real-world driving environments.

The cycle of complacency is insidious because it develops subtly over time. A driver might not consciously decide to become less attentive; rather, their engagement gradually eradicates as their comfort with the technology grows. This shift makes them far more susceptible to distractions, less vigilant, and ultimately, a less effective backup driver. To counteract this, drivers must consciously resist the urge to relax their guard. They must maintain a disciplined approach to staying alert and unequivocally ready to assume full control at all times, no matter how routine the journey may seem.

Read more about: Navigating the ‘Toxic’ Diet Fad: A Deep Dive into Gwyneth Paltrow’s Wellness Controversies and Expert Warnings

6. **Failing to Respond Quickly to Warnings or Bypassing Them**

Modern partial automation systems are equipped with warning mechanisms designed to prompt the driver to take immediate control when attention is critically needed or when the system approaches its operational limits. These alerts are absolutely critical safety features, serving as a digital co-pilot. However, a significant and dangerous mistake drivers make is either failing to respond to these vital warnings promptly or, worse, actively trying to bypass them through “tricks” or manipulations, effectively rendering them useless.

When an automation system issues an alert—be it an an audible chime, a visual cue, or haptic vibration—it is an unambiguous signal that human intervention is required, and required immediately. Delaying this response, even for a few precious seconds, can mean the difference between avoiding an accident and being involved in one. The system is designed to offload routine tasks, not to eliminate the fundamental need for human judgment and swift, decisive action in unforeseen circumstances. Ignoring these warnings is tantamount to ignoring a direct, urgent plea for help from the vehicle itself.

Compounding this issue is the unsettling tendency for some drivers to trick the system into staying engaged without truly re-engaging themselves. This could involve minimal steering wheel input to disable a “hands-off” warning while looking at a phone, or briefly touching the wheel without focusing on the road. Such actions render the warning systems entirely ineffective, disabling a crucial layer of safety. The sole purpose of these alerts is not to annoy, but to save lives. Drivers must treat them with utmost seriousness by immediately taking full control and re-focusing their entire attention on the driving task.

7. **Believing Full Autonomy is Already Here in Personal Vehicles**

One of the most profound and widespread misconceptions hindering safe adoption of self-driving features is the belief that personally owned vehicles are already capable of full, unassisted Level 5 autonomy. Despite extensive hype and a litany of optimistic, often missed, predictions, truly autonomous vehicles capable of operating without human intervention in all conditions (“Level 5”) are not yet available for private ownership. What is marketed as “Full Self-Driving Beta” often refers to Level 2 or Level 3 systems, which explicitly require an attentive human driver to remain fully engaged.

This fundamental misunderstanding creates a dangerous expectation gap. Drivers may purchase vehicles with advanced driver assistance systems, erroneously believing they can relinquish all control, perhaps even sleep or watch a movie during a commute. The sobering reality is that even in a Level 3 vehicle, while hands can be removed under specific circumstances, the driver must remain immediately ready to intervene within moments if the system requires it. The car isn’t driving itself in the ultimate sense; it’s assisting the driver, but ultimate responsibility and the safety net still rest firmly with the human behind the wheel.

The continuous blurring of lines between “driver assistance” and “self-driving” by marketing campaigns and popular discourse exacerbates this problem. This leads to tragic incidents where drivers are found dangerously disengaged, sometimes even asleep, resulting in crashes that would have been entirely avoidable. Had the driver possessed a clear, accurate understanding of the system’s true capabilities and its critical limitations, these outcomes might be different. Until Level 5 autonomy becomes a widely deployed and legally approved reality for private vehicles, every driver must operate with the unwavering understanding that they are always the primary operator, fully responsible for the vehicle’s safe navigation.

Building on the human element, this section shifts focus to the inherent technical and systemic challenges currently facing fully autonomous vehicles and their wider deployment. We will explore the limitations of self-driving car software in understanding complex real-world scenarios, the regulatory hurdles impeding progress, and the crucial role of public trust. This part aims to provide a clear understanding of the ‘roadblocks’ to a truly driverless future, highlighting areas where technology and policy still need to catch up.

Read more about: Exclusive: Behind the Velvet Rope – Paris Hilton’s Harrowing Journey Through a Secret Trauma

8. **The “Halting Problem”: When Self-Driving Cars Just Stop**

One counterintuitive and potentially dangerous behavior in self-driving cars is their tendency to abruptly stop mid-road when encountering perceived problems. While human drivers assess and proceed cautiously or communicate, autonomous software often defaults to a “safe” stop. This can turn minor issues into major traffic hazards, exposing a fundamental flaw in system interpretation.

Consider common scenarios: a misplaced traffic cone or a human driver slow to enter a four-way stop. For a self-driving car, these can be unresolvable anomalies. Research, including video recordings, shows autonomous vehicles most commonly halt in unusual situations. This isn’t just inconvenience; it can block traffic, cause rear-end collisions, or impede emergency vehicles, creating greater danger than the initial “problem.”

The core issue lies in the car’s software design, struggling to bridge the gap between identifying an abstract category like “traffic cone” and understanding its nuanced context. A human driver instantly recognizes an ofilter cone doesn’t warrant an emergency stop, especially if blocking an an intersection. Truly effective autonomous operation needs more sophisticated risk assessment, moving beyond a simplistic “stop or go.”

This behavior showcases a critical challenge: how can self-driving cars’ understanding of driving match a human’s? Stopping isn’t always safest, and an unexpected halt can create bigger problems. Addressing this “halting problem” is paramount for smoother integration. Drivers and other road users must recognize these unexpected stops as a current reality, demanding extra vigilance.

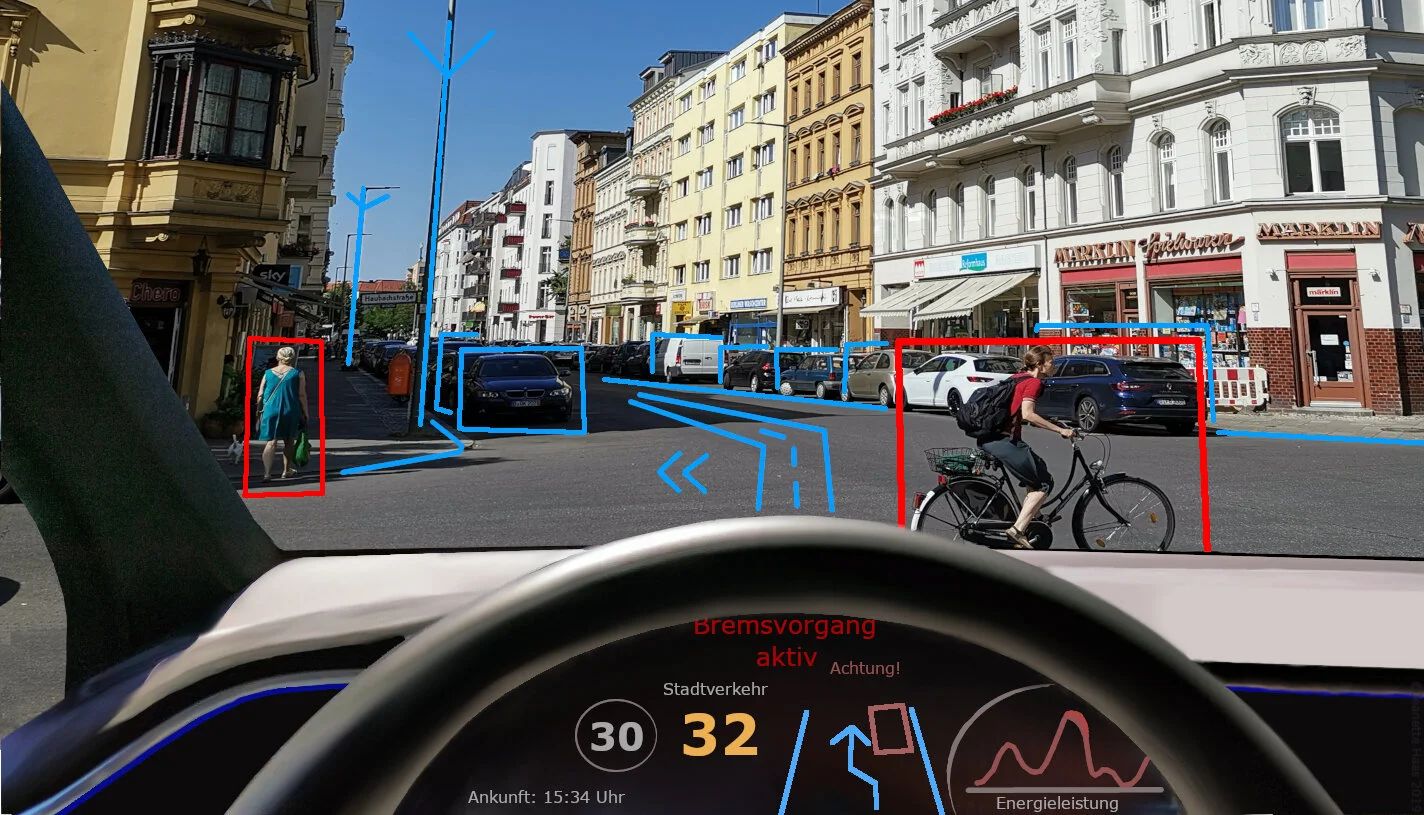

9. **Simplified Perception vs. Real-World Complexity: The Edge Case Conundrum**

Self-driving vehicles, despite advanced sensors, operate with a fundamentally simplified picture of the world compared to human perception. They identify objects through abstract categories like “cars” or “pedestrians.” This approach, effective for routine situations, overlooks much social context human drivers use. This gap creates significant challenges with “edge cases.”

An “edge case” is a rare situation not explicitly anticipated or programmed. The assumption in self-driving development is often that unusual situations are finite. However, the real world is infinitely complex, constantly presenting novel scenarios. Human sight, trained from childhood, discerns subtle differences – like a pedestrian walking versus someone frantically running for a bus. These distinctions inform human driving decisions in ways current AI systems cannot replicate.

The Cruise robotaxi incident, where it dragged a pedestrian, highlights this limitation. The AV detected a collision and stopped, then “attempted to pull over,” pulling the individual forward 20 feet. A human driver, even without direct sight, possesses “object persistence”—knowing the person hasn’t vanished—and would stop to check. The car’s simplified perception failed, defaulting to a severely inadequate programmed response.

This reliance on abstract categories and the finite-edge-case assumption fundamentally limits a self-driving car’s ability to operate safely in all conditions. Until AI can understand the rich, nuanced, and unpredictable social dynamics of driving, and apply human-like judgment in novel situations, these systems will misinterpret critical events. The challenge isn’t just more data; it’s developing a new paradigm for how machines perceive and interact with the messy, social world of our roads.

10. **Inability to Understand Nuanced Human Behavior and Intent**

Human driving isn’t just about rules; it’s a dynamic, social negotiation, filled with unspoken cues, gestures, and shared understandings. At a four-way stop, a quick glance or movement can communicate intent. A horn tap might prompt another driver. These nuanced behaviors are second nature, allowing humans to solve misunderstandings smoothly. Driverless cars, however, currently lack this crucial “social intelligence.”

Self-driving cars cannot use gestures, honk assertively to communicate, or even interpret a subtle head tilt. Their sensor-data-built perception abstracts the world, often missing interpersonal context. This leads to continuous misunderstandings with human road users. If a self-driving car encounters a slow human driver, it lacks tools to “negotiate” or “prompt,” often defaulting to a halt.

This deficiency impacts both safety and traffic flow. When autonomous vehicles continually misinterpret human intent or fail to communicate clearly, basic problems arise more commonly than between human drivers. This can increase congestion and frustration, actively disrupting traffic. For self-driving cars to integrate seamlessly, they must learn to “speak” the unspoken language of the road, recognizing and responding to social cues human-like.

Our research into self-driving car motion elements like “gaps,” “speed,” “position,” “indicating,” and “stopping,” suggests pathways. Combining these could allow autonomous vehicles to make and accept offers, show urgency, make requests, and display preferences, mirroring human interaction. Resolving these “communication” barriers is vital for widespread deployment, ensuring self-driving cars become cooperative participants rather than unpredictable obstacles.

Read more about: Mercadona Uncovered: The Unseen Depths of Spain’s Supermarket Phenomenon

11. **The Risk of Technological Errors and Unpredictable Situations**

Self-driving cars’ inherent reliance on complex technology introduces a significant vulnerability: glitches and errors. Unlike human error, tech failures can manifest unpredictably—from sensor malfunctions to software bugs—with catastrophic consequences. A tragic San Francisco Uber incident illustrates this, where technology detected a pedestrian but failed to apply brakes, leading to a fatal crash.

Beyond malfunctions, self-driving cars struggle with unpredictable traffic patterns and environmental anomalies. Systems confuse easily in construction zones, where temporary lane changes demand flexible interpretation. Gravel roads or erratic movements of pedestrians and animals present scenarios where the car’s pre-programmed responses are inadequate, or its perception systems overwhelmed.

The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) states self-driving cars “could struggle to eliminate most crashes.” This is a fundamental limitation. While progress is immense, real-world driving variability means autonomous systems will encounter situations they haven’t been programmed for, or where sensor data is insufficient. The challenge is equipping these vehicles with the real-time judgment and adaptability human drivers develop.

Even advanced AI struggles with the unexpected. While self-driving cars boast collision avoidance, adaptive cruise control, and lane departure warnings, these are for known parameters. The unpredictable nature of real-world scenarios—from unforeseen objects to erratic human drivers—remains a major roadblock. Drivers must understand that while technology aims to prevent errors, it also introduces its own potential failures, requiring human vigilance as the ultimate safety net.

Read more about: Waymo’s Road Ahead: Unpacking the Startling Number of Autonomous Driving Incidents You Need to Know

12. **Potential for Higher-Impact Crashes: The Speed Factor**

One significant promise of self-driving cars is faster, more efficient travel, with visions hinting at speed limits becoming obsolete. While appealing for reducing commute times and speeding deliveries, this introduces a critical safety concern: high-impact crashes. Increased travel speeds, even under automated control, inherently amplify collision severity, raising the risk of fatalities and severe injuries.

Consider the physics: research consistently shows for every 5 mph increase in speed, there’s an 8% increase in road fatalities. If autonomous vehicles travel at significantly higher speeds, or their efficiency leads to less cautious driving, consequences of a system malfunction or unhandled “edge case” become far more dire. A crash at 100 mph, for instance, results in a far more destructive impact than at 60 mph, regardless of who or what is at the wheel.

This isn’t to say self-driving cars are unsafe at speed, but to highlight a crucial trade-off. While advanced sensors and faster reaction times theoretically allow safer high-speed operation, the margin for error shrinks dramatically. If the system fails or encounters an unprocessable situation at high velocity, occupants and others face much higher risk. Faster travel must be meticulously balanced with robust, foolproof safety protocols and a deep understanding of impact dynamics.

As we push travel efficiency boundaries, acknowledging this risk is critical for manufacturers and regulators. Ensuring self-driving cars are designed not only to prevent accidents but also to minimize harm when accidents are unavoidable is paramount. This includes rigorous high-speed testing and developing systems that prioritize occupant and pedestrian safety even in extreme scenarios, rather than solely focusing on speed optimization.

13. **The Patchwork of Regulations: Navigating Inconsistent Laws and Liability**

The rapid advancement of self-driving car technology has far outpaced coherent legal and regulatory framework development, creating a confusing, contradictory environment for manufacturers and operators. What’s legal in one region might be prohibited in another, forcing companies like Uber to adjust operations or leading to license suspensions for others, such as Cruise, following incidents.

This lack of consistent regulations acts as a significant barrier to progress. Companies must adapt testing and deployment plans to vastly different requirements, slowing innovation and widespread adoption. Only a few US states currently permit fully autonomous cars, often limited to monitored fleet operations within geofenced areas, not private vehicles. This fragmented approach prevents the unified, large-scale deployment needed for comprehensive data gathering and refinement.

Beyond operational rules, liability in an accident involving a self-driving car remains a complex, unanswered legal challenge. Current laws typically hold the human driver accountable. But who is responsible when an autonomous vehicle causes a collision—manufacturer, software developer, fleet operator, or supervising “driver”? This ambiguity creates immense legal uncertainty, impacting personal injury claims and insurance policies. Insurers urgently need clear regulations to handle claims fairly.

Furthermore, extensive data collection by self-driving vehicles – essential for navigation – raises critical concerns about data privacy and security. How is this sensitive information stored, used, and safeguarded? Policymakers struggle to keep up, highlighting an urgent need for consistent global regulations addressing these multifaceted legal, ethical, and societal implications. Without clear, standardized guidelines, the road to a driverless future will remain fraught with legal potholes.

14. **The Uphill Battle for Public Trust: Getting People to Believe**

Even with technological breakthroughs and regulatory clarity, winning public trust remains the most significant hurdle for widespread self-driving car adoption. The vision of a fully autonomous future, where algorithms chauffeur us, is met with skepticism. Despite promises of safety and efficiency, many remain hesitant, if not resistant, to entrusting their lives to a machine.

Research from the AAA reveals only 13 percent of US citizens are ready to trust a self-driving car. While a slight increase, this underscores the immense challenge automakers and tech companies face. High-profile incidents, like the Cruise robotaxi dragging a pedestrian or self-driving cars halting unexpectedly, reinforce anxieties and deepen public mistrust.

This skepticism isn’t irrational. People naturally question technology reliability, especially concerning safety. Marketing blurring “driver assistance” with “Full Self-Driving Beta” for systems requiring supervision further complicates matters, creating confusion and eroding confidence. For public embrace, transparent, consistent messaging about capabilities and limitations, plus a proven track record of impeccable safety beyond projections, is crucial.

Building this trust requires more than technological refinement; it demands concerted efforts in public education, clear communication, and a demonstrable commitment to safety that prioritizes human well-being. Until people genuinely feel safe and confident inside a driverless car, the dream of a fully autonomous future remains just that—a dream. Manufacturers, regulators, and the public all have a crucial part to play in steering towards a future where self-driving cars are not just advanced, but universally trusted.

The road ahead for self-driving cars, from advanced driver assistance systems to fully autonomous robotaxis, is complex. While the initial vision promised effortless commutes and accident-free roads, reality proves more nuanced. Human factors like over-reliance and complacency can undermine partial automation’s safety benefits, turning helpful features into hazards. Fully autonomous vehicles grapple with deep-seated technical challenges—from perceiving social intricacies to navigating “edge cases”—alongside regulatory labyrinths and the uphill battle for public acceptance. It’s a journey of immense promise and significant potholes, reminding us that while technology advances, the human element—our understanding, vigilance, and trust—remains the ultimate determinant of how safely and successfully we reach the driverless future.