Susan Brownmiller, a towering figure in American feminism whose landmark 1975 book, “Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape,” fundamentally reshaped the national conversation about sexual assault, has died at the age of 90. Her passing on Saturday at a New York hospital, after a long illness, marks the end of a remarkable life dedicated to challenging societal norms and confronting difficult truths, leaving behind a legacy of profound change and persistent debate.

Brownmiller was not only an author but also a journalist and a tireless activist, whose relentless pursuit of justice and understanding propelled the “second wave” feminist movement into new territory. Her work on “Against Our Will” was described by Emily Jane Goodman, the executor of her will and a longtime friend, as a “landmark and intensely debated bestseller” that continued to be widely read and taught for decades after its publication. The book’s influence led to tangible reforms, inspiring survivors to speak out, fostering the creation of rape crisis centers, and contributing to the passage of vital marital rape laws.

Indeed, Ms. Brownmiller asked her readers to rethink everything they thought they knew — about Western civilization, their own attitudes, the law, and social science. Her contributions were, by design, controversial, emerging from a tradition of radical political movements that shaped her unique insights and unyielding commitment to social justice. As Alix Kates Shulman, a fellow writer and feminist, observed, “We were women’s liberation comrades,” underscoring the deep bonds and shared purpose that defined this transformative era.

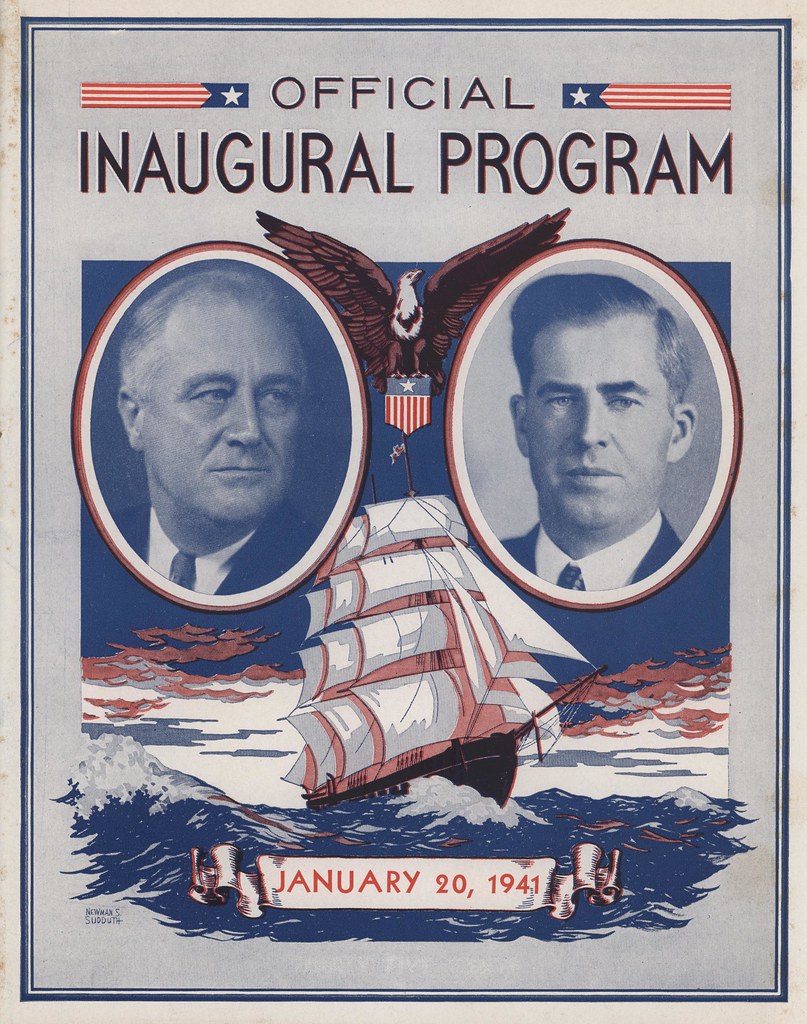

1. **Early Life, Jewish Heritage, and Unfulfilled Acting Aspirations**Born Susan Warhaftig in Brooklyn, New York City, on February 15, 1935, Susan Brownmiller was the only child of Mae and Samuel Warhaftig, a lower-middle-class Jewish couple. Her father, an immigrant from a Polish shtetl, worked as a salesman in the Garment Center and later at Macy’s department store, while her mother served as a secretary in the Empire State Building. This background instilled in her an early intensity for current events and politics, as both her parents were devoted followers of Franklin Roosevelt and highly knowledgeable about contemporary affairs.

Ms. Brownmiller attended Hebrew school for two afternoons a week, a formative experience that, despite its fragmented recollection, left a singular thread: “a helluva lot of people over the centuries seemed to want to harm Jewish people.” She would later connect this early learning to her life’s mission, stating, “I can argue that my chosen path — to fight against physical harm, specifically the terror of violence against women — had its origins in what I had learned in Hebrew School about the pogroms and The Holocaust.” After attending Cornell University on scholarship for two years, she harbored a “very mistaken ambition” to become a Broadway star, working as a file clerk and waitress while hoping for roles that never materialized. It was during this period, in the mid-1950s, that she adopted the stage name Brownmiller, legally changing it in 1961, a name that would become synonymous with a radical new discourse on gender.

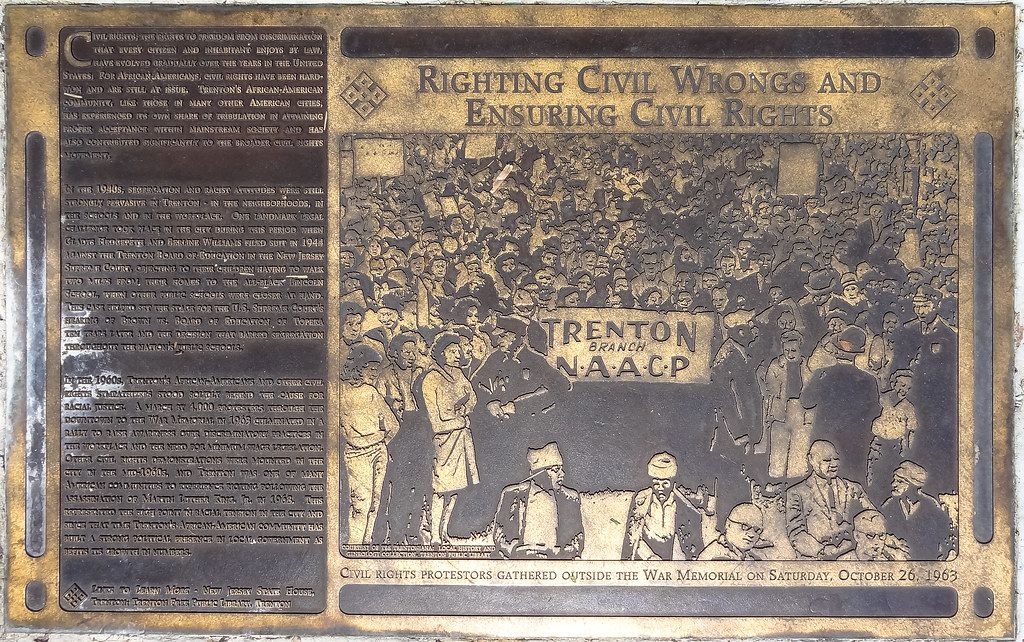

2. **Forged in the Fires of Civil Rights Activism**Before her deep dive into second-wave feminism, Susan Brownmiller was a fervent participant in the burgeoning civil rights movement of the 1960s. Her radicalization began early, as she joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1960 and later became involved with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the sit-in movement. Her commitment to social justice was profoundly demonstrated in 1964, when she volunteered for “Freedom Summer,” traveling to Meridian, Mississippi, to help register Black people to vote. This experience, recounted by Brownmiller, involved confronting racial prejudice even within the movement itself, as a field secretary expressed frustration at being sent “white women” instead of other volunteers.

Her experiences in the Civil Rights Movement were pivotal, serving as a crucible for her activist spirit. She was among many women of her generation who found their voices and radicalized their perspectives through direct engagement with the era’s most pressing social and political struggles. The movement’s emphasis on direct action and systemic change provided a foundational framework for her later feminist activism, demonstrating how entrenched social structures could be challenged and transformed. This period laid the groundwork for her understanding of power dynamics and oppression, which would profoundly inform her most famous work.

Read more about: Let’s Talk Madonna: Why The Queen of Pop’s Iconic Reign Continues to Challenge Every Expectation, Age Included

3. **A Career Rooted in Incisive Journalism**Susan Brownmiller’s path to becoming a groundbreaking author was paved through a diverse and robust career in journalism. Her initial foray into writing began with an editorial position at a “confession magazine,” a practical start that quickly led to more substantive roles. From 1959 to 1960, she served as an assistant to the managing editor at Coronet, and from 1961 to 1962, she edited the Albany Report, a weekly review of the New York State legislature. These early experiences honed her skills in research, analysis, and concise communication, which would become hallmarks of her later work.

In the mid-1960s, Ms. Brownmiller continued to build her journalistic portfolio, working as a national affairs researcher at Newsweek, a staff writer for The Village Voice, and a network news writer for ABC-TV in New York City. She also freelanced for various magazines, demonstrating her versatility and an expanding command of different journalistic forms. This period of intense engagement with media and news reporting provided her with an insider’s view of how information was shaped and disseminated, and equipped her with the tools to meticulously research and articulate complex social issues, preparing her for the monumental task of writing “Against Our Will.”

4. **The Birth of a Second-Wave Feminist Voice**Susan Brownmiller’s full immersion into the Women’s Liberation Movement began in New York City in 1968. She became an active participant in a consciousness-raising group within the newly formed New York Radical Women organization, a pivotal experience where women shared their personal stories and collectively theorized about systemic oppression. It was in this intimate setting that she openly discussed her three illegal abortions, illustrating the raw and personal nature of the discussions that fueled the movement.

Her activism quickly escalated beyond consciousness-raising. Brownmiller became an informal leader within the West Village-1 brigade of the New York Radical Feminists, an organization formed in late 1969. In March 1970, she played a key role in coordinating an infamous sit-in against Ladies’ Home Journal, protesting the magazine’s traditional focus on beauty and housework and the significant underrepresentation of women on its editorial staff. This bold act of defiance underscored her combative and assertive style, establishing her as a formidable voice within the rapidly evolving feminist landscape. Such public demonstrations and internal organizing showcased her ability to galvanize women and challenge powerful institutions directly.

5. **”Against Our Will”: Genesis of a Landmark Work**The conceptualization of “Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape” emerged directly from the ferment of the feminist movement. In 1970, after attending a consciousness-raising session, Ms. Brownmiller helped organize a rape “speak-out” and a subsequent rape conference in 1971. It was at this moment that she recognized the profound, yet largely unaddressed, nature of sexual assault as a central feminist issue, immediately knowing that this would be her subject. This realization sparked a four-year odyssey of meticulous research and writing, primarily conducted within the extensive archives of the New York Public Library.

Her timing coincided with a global awakening to the atrocity of wartime rape. Just as Brownmiller was beginning her research in 1971, Pakistani invaders in Bangladesh were perpetrating mass rapes on an unprecedented scale, affecting between 200,000 and 400,000 women and leading to widespread trauma, ostracization, and thousands of abortions, infanticides, and suicides. Ms. Brownmiller noted that while such patterns of wartime sexual violence had occurred throughout history, this was the first time the world had acknowledged the atrocity in real time. This stark contemporary context underscored the urgency and profound relevance of her project, providing a crucial backdrop for her comprehensive historical and sociological analysis of rape.

6. **Redefining Rape: The Core Arguments**“Against Our Will” shattered prevailing myths and irrevocably altered the discourse surrounding sexual assault by fundamentally redefining rape. Susan Brownmiller argued strenuously against the entrenched societal view that rape was primarily an act of lust or passion, instead reframing it as a deliberate act of power and violence. Her central thesis, meticulously researched and forcefully articulated, asserted that rape served as a conscious process of intimidation by which all men, whether actively perpetrating or implicitly benefiting from the threat, maintained all women in a state of fear. This bold assertion, italicized in her book, became its most famous and, simultaneously, most disputed claim.

Brownmiller documented the historical roots, pervasive prevalence, and intricate politics of rape, spanning from ancient Babylon through its use as a military tactic in wartime, against children, and within marital relationships. She explicitly denounced the glorification of rape in popular culture, contending that it was never about desire but always about dominance. Her anatomical argument, “Man’s structural capacity to rape and woman’s corresponding structural vulnerability are as basic to the physiology of both our sexes as the primal act of sex itself,” presented a stark and unromanticized view of the power imbalance inherent in male-female relations. The book tirelessly worked to debunk male-generated myths, asserting unequivocally that women do not secretly wish to be sexually assaulted and that, yes, it is indeed physically possible to be raped against one’s will, thus empowering victims and challenging centuries of victim-blaming.

7. **Widespread Acclaim and Societal Shift**The publication of “Against Our Will” in 1975 was met with immediate and widespread acclaim, catapulting it onto best-seller lists and securing its place as a monumental work of scholarship and social commentary. It was chosen as a main selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club, a testament to its broad appeal and perceived newsworthiness, leading to Ms. Brownmiller being interviewed on the TODAY show by Barbara Walters. Its influence quickly transcended national borders, being translated into a dozen languages, and was later ranked by The New York Public Library as one of the 100 most important books of the 20th century. In 1976, Time magazine recognized her profound impact by placing her picture on its cover, alongside Billie Jean King, Betty Ford, and nine others, as “Women of the Year.”

The book’s intellectual rigor and provocative insights led to high praise from critics; the lawyer Mary Ellen Gale described it as “Chilling and monumental” in The New York Times Book Review, while Time magazine hailed it as “The most rigorous and provocative piece of scholarship that has yet emerged from the feminist movement.” More importantly, “Against Our Will” inspired profound societal change. It empowered survivors to share their stories, spurred women to organize and establish numerous rape crisis centers, contributed significantly to the passage of marital rape laws, and led many jurisdictions to abolish the “corroborating witness rule” and implement rape shield laws, fundamentally transforming legal and social responses to sexual assault across the country. Her call to action, “Fighting back,” became an enduring rallying cry for women seeking to redress the imbalance of power and eradicate the ideology of rape.” , “_words_section1”: “1948

Read more about: The Engines of Legend: How Iconic Vehicles Drive Cinematic Narratives and Automotive Innovation

8. **The Storm of Controversy and Critiques**While “Against Our Will” garnered immense praise and reshaped public discourse, its bold assertions also ignited a fierce storm of controversy and outrage, a reaction Susan Brownmiller herself likely anticipated given the radical nature of her claims. Her central thesis – that rape “is nothing more or less than a conscious process of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear” – proved to be its most famous, and most disputed, statement. This generalization, equating all men with the threat of sexual violence, led to her being harassed on the lecture circuit for years, as even some admirers “squirmed” at the breadth of the assertion.

Critiques emerged from across the political spectrum, highlighting the complex divisions within and outside the burgeoning feminist movement. On the left, Black feminist intellectuals like Angela Davis and bell hooks sharply criticized Brownmiller’s attempts to weave the crime of lynching into her theory of gender and power, particularly her “clumsy and confounded” handling of the Emmett Till lynching. Davis argued that Brownmiller’s views were “pervaded with racist ideas,” misinterpreting historical cases involving Black men and white women by concluding, wrongly, that Black men were at fault and that her analysis “capitulates to racism.” Later, in 2017, New Yorker editor David Remnick called her writing about Till’s murder “morally oblivious,” a criticism Brownmiller dismissed in 2015, stating she stood by “every word.”

From the conservative right, Joseph Sobran, writing in National Review, openly mocked Brownmiller’s premise, declaring, “What she is engaged in, really, is not scholarship but henpecking — that conscious process of intimidation by which all women keep all men in terror.” Beyond these external critiques, some radical feminists, who had always been uncomfortable with Brownmiller’s high media profile, deplored her use of ideas developed in consciousness-raising sessions, even challenging her to remove her name from the book. These multifaceted reactions underscored the deeply provocative nature of her work and its challenge to established norms, ensuring its place as a text of persistent debate.

Read more about: D.C. Under Siege? Federal Law Enforcement Presence Sparks Outrage and Confrontation on Busy City Streets

9. **Later Contentious Stances on Victim Responsibility**Decades after the groundbreaking publication of “Against Our Will,” Susan Brownmiller’s views continued to spark controversy, particularly her later comments on victim responsibility in cases of sexual assault. In 2015, on the 40th anniversary of her book, Brownmiller, then 80, stood by her original work but voiced highly critical opinions about contemporary young women. She suggested that young women who drink heavily or dress provocatively might share some responsibility if they were sexually assaulted, implying they failed to heed “warning signs.”

Speaking to New York magazine that year, she stated, “My feeling about young women trapped in sex situations that they don’t want is: ‘Didn’t you see the warning signs? Who do you expect to do your fighting for you?’ It is a little late, after you are both undressed, to say ‘I don’t want this.’” She expanded on this perspective in an interview with Al Jazeera, asserting that women were “in denial” about what they could and could not do. She contended that women “don’t want to feel that special restrictions apply to them” and possess a “false sense of empowerment” because, in truth, “they can’t do everything men can do. Because there are predators out there.”

These later pronouncements stunned and angered many, particularly budding feminists, who saw them as a stark contradiction to her earlier anti-victim-blaming stance. Amanda Marcotte of Slate famously branded Brownmiller a “former feminist hero,” criticizing her for believing that rapists “are like the weather and it’s the victim’s fault for not bringing an umbrella.” Marcotte argued that Brownmiller should instead be addressing men and the pervasive culture of sexual violence, rather than shifting responsibility back to victims, a position that seemed to undermine the very foundations of “Against Our Will” and her legacy of empowerment.

Read more about: Red Flags Raised: Unraveling the Shocking Claims and Lingering Questions Around Hulk Hogan’s Cause of Death

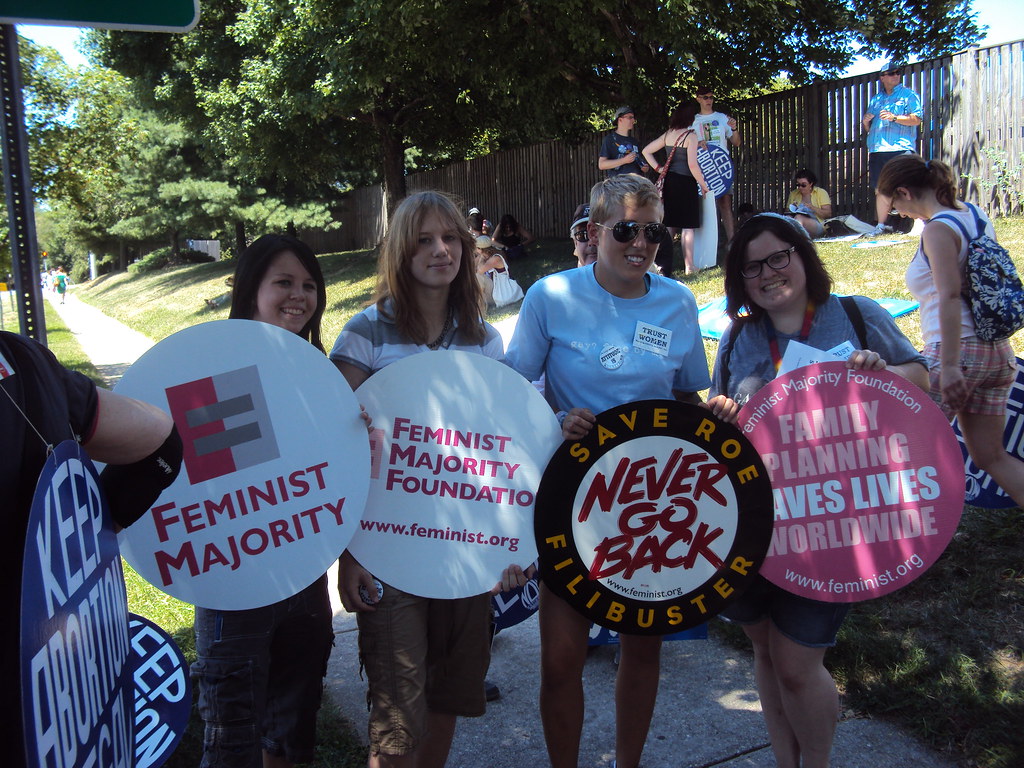

10. **Leading the Charge Against Pornography**Susan Brownmiller’s combative and assertive style, evident in her redefinition of rape, also fueled her vociferous opposition to the multi-billion-dollar pornography industry. She firmly believed that the dehumanization of women inherent in pornography was a significant contributor to sexual violence, asserting that it degraded and abused women. This conviction led her to become a pivotal figure in anti-pornography activism during the late 1970s and early 1980s, expanding her focus beyond sexual assault to the cultural artifacts she saw as enabling it.

Her commitment to this cause manifested in concrete actions, including co-founding the New York chapter of “Women Against Pornography” in 1979, alongside other influential feminists like Gloria Steinem and Adrienne Rich. As part of this organization, Brownmiller took on the role of a tour guide, leading educational excursions through the then-seedy Times Square, pointing out the myriad porn shops and neon signs to highlight what she saw as the blatant objectification of women. A 1979 report in The Times noted her professional delivery, which even drew in unsuspecting tourists.

Brownmiller also penned an influential essay, “Let’s Put Pornography Back in the Closet,” in which she forcefully disputed arguments that pornography was protected by the First Amendment. This stance, however, created a significant ideological split within the women’s movement, dividing anti-pornography feminists from “sex-positive” feminists and others who viewed a ban as prudish and a violation of free speech. Despite this internal conflict, Brownmiller held firm, opposing the legislative push by anti-porn leader Catherine MacKinnon, believing instead that pornography was best confronted through education and public protests. Although the anti-pornography crusade eventually waned and was largely considered a “lost cause” in feminist history, Brownmiller’s fierce advocacy underscored her unyielding commitment to challenging all forms of female subjugation.

Read more about: Andrew Cuomo: Charting a Divisive Political Trajectory from Queens to New York’s Pinnacle

11. **A Diverse Literary Output Beyond Rape**While “Against Our Will” remains her most celebrated and defining work, Susan Brownmiller’s literary career was far more diverse, encompassing a range of non-fiction and even a venture into fiction. Her prolific writing began early, with an editorial position at a “confession magazine” and later as a researcher and writer for various news outlets. Her earliest known book, published in 1970, was a children’s book about Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress, showcasing an early interest in celebrating pioneering women.

In 1984, she published “Femininity,” a comprehensive deconstruction of the meaning and societal expectations associated with the word. This was followed by her 1989 novel, “Waverly Place,” a fictionalized account inspired by the sensational 1987 domestic violence case of lawyer Joel Steinberg, who brutally abused his partner, Hedda Nussbaum, and killed their adopted daughter. In a foreshadowing of her later contentious views on victim responsibility, Brownmiller argued within the context of the novel that Nussbaum was not merely a passive victim but should have been held partly accountable for the child’s death, a stance that garnered mixed reception.

Her later non-fiction works included “Seeing Vietnam: Encounters of the Road and Heart” in 1994, a travelogue reflecting her experiences in Vietnam, and “In Our Time: Memoir of a Revolution” (1999), an insider’s account offering her personal reflections on the women’s movement. While these books demonstrated her versatility and continued engagement with social issues and personal history, none achieved the widespread recognition or monumental impact of “Against Our Will.” Yet, they collectively paint a picture of a writer deeply committed to exploring complex societal constructs and personal narratives throughout her long career.

Read more about: California’s Grand Narrative: Unpacking the Golden State’s Complex Landscape, Rich History, and Enduring Challenges

12. **A Life Beyond the Page: Personal Connections and Generosity**Beyond her public persona as a combative feminist author and activist, Susan Brownmiller was remembered by her friends as a fundamentally generous, good person with a terrific sense of humor, deeply invested in her personal relationships. She lived for decades in her Greenwich Village apartment, a place that hosted “remarkable gatherings,” including regular poker nights, reflecting a vibrant social life that balanced her intense political engagement.

Her loyalty and generosity toward her friends were legendary, with long-time companions like Emily Jane Goodman, the executor of her will, and fellow feminist writer Alix Kates Shulman, who cherished their “women’s liberation comradeship.” Brownmiller frequently used her influence to support other women, as evidenced by her archived correspondence, which is full of instances where she connected women with agents and editors, encouraged their writing endeavors, and boosted their self-confidence. A notable anecdote recounts how, during her ABC news-writing days in the 1960s, she inspired a female assistant to quit her job and pursue her own journalism career by asking, “Why aren’t you in charge?” This woman became a lifelong friend.

Brownmiller also cultivated a rich personal life, enjoying dogs, theater, movies, poker, and baseball, illustrating a well-rounded individual whose passions extended beyond activism. While she lived with three different men over the years, she never married and chose not to have children, having had three abortions. She once expressed her belief in “romance and partnership” and a desire to be “in close association with a man whose work I respect,” but emphasized she was “not willing to compromise.” In her later years, she continued her generosity, playing a similar mentorship role for numerous researchers, as biographer Claire Bond Potter warmly recalled in her own account of their initial meeting, highlighting Brownmiller’s readiness to connect her with other movement veterans, ushering in “the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

13. **Reflections on a Movement: Despair and Enduring Hope**As the intense fervor of the second-wave feminist movement began to wane in the 1980s, Susan Brownmiller, ever the keen observer, reflected with a degree of despair on its evolution. In her 1999 memoir, “In Our Time: Memoir of a Revolution,” she candidly noted her sadness over the “slow seepage, symbolic defeats and petty divisions” that she believed were both causes and symptoms of the movement’s decline. This introspection revealed the emotional toll of sustained activism and the challenges of maintaining solidarity within a broad-based social revolution.

Despite this period of disillusionment, Brownmiller’s core conviction in the power and necessity of feminist action remained unshaken. She continued to remember the early years of the movement as a “rare and precious chapter,” a time when “the vision is clear and the sisterhood is powerful, mountains are moved and the human landscape is changed forever.” This unwavering belief in feminism’s transformative potential highlighted her enduring optimism, even amidst perceived setbacks.

Brownmiller consistently took pride in the profound impact of her work, particularly “Against Our Will,” on the national conversation surrounding sexual assault. In a 2013 preface for a new edition of her landmark book, she applauded “some amazing developments in the effort to combat sexual assault that could not have been anticipated several decades ago.” She expressed deep satisfaction that the attention she and her book received played a crucial role “in the groundbreaking effort to reverse the traditional wisdom on assaultive acts against women and children,” affirming her legacy as a catalyst for systemic change.

14. **An Unmistakable Legacy of Transformation and Debate**Susan Brownmiller, a singular figure in American feminism, leaves behind an unmistakable legacy that fundamentally reshaped the national and international conversation about sexual assault. Her landmark work, “Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape,” did more than just document the roots and prevalence of sexual violence; it irrevocably redefined rape, moving it from the realm of lust to that of power and violence, a crime used “to generate fear” and maintain male dominance. This reframing empowered survivors, spurred the creation of rape crisis centers, and led to tangible legal reforms, including marital rape laws and rape shield protections, truly changing the “human landscape forever.”

Yet, her contributions were “controversial by design,” emerging from a tradition of radical political movements that embraced conflict and debate as pathways to transformation. From her assertion that “all men” maintain women in a state of fear, to her contentious views on victim responsibility, and her leadership in the anti-pornography movement, Brownmiller consistently provoked discussion and challenged deeply ingrained societal attitudes. These debates, often heated and divisive, underscore the enduring relevance of her ideas and her willingness to confront uncomfortable truths, ensuring her place as a figure whose work continues to be taught, discussed, and argued over for decades.

In her passing at 90, Susan Brownmiller leaves behind not just seven books and a prolific journalistic career, but a transformed public discourse about sex and gender. Her “Fighting back” rallying cry became a symbol for women seeking to redress imbalances of power and dismantle the “ideology of rape.” Her intellectual rigor, combative spirit, and unyielding commitment to social justice have left an indelible mark, ensuring that the critical dialogue around gender, violence, and empowerment she helped initiate will continue to evolve and inspire future generations to challenge, question, and ultimately, fight for a more just world.

Read more about: 12 Iconic Rides from Movies & TV That Drove Straight Into Our Hearts

Susan Brownmiller’s life exemplified the power of a single voice to ignite a revolution in thought and action. Through her unwavering dedication, she asked us to rethink everything we thought we knew, fundamentally altering our understanding of a pervasive societal ill and, in doing so, inspired a generation to confront and challenge the status quo. Her legacy is one of profound transformation, persistent debate, and a call to action that continues to resonate with undeniable force.