Sydney, the expansive capital city of New South Wales, stands as a testament to evolution, resilience, and global influence. For those seeking to comprehend the intricate tapestry of a truly dynamic metropolis, exploring Sydney offers a compelling case study. It is a city that seamlessly blends ancient Indigenous heritage with a vibrant, modern-day global presence, continuously shaping its identity on the global stage.

At its heart, Sydney is not merely a city; it is a living, breathing entity that encompasses a vast geographic expanse. Situated on Australia’s eastern coastline, this metropolis famously encircles Sydney Harbour, extending an impressive 80 kilometers (50 miles) from the Pacific Ocean in the east to the rugged Blue Mountains in the west. Its scope extends equally far, from Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park and the Hawkesbury River in the north and northwest, down to the Royal National Park and Macarthur in the south and southwest. This vast area, encompassing 658 suburbs spread across 33 local government areas, is home to a population colloquially known as “Sydneysiders”.

Understanding Sydney commences with its impressive scale and demographic composition. As of June 2024, the estimated population surged to 5,557,233, accounting for approximately 66% of New South Wales’ total population. This concentration of people highlights the city’s undeniable magnetic appeal. Affectionately known by nicknames such as the “Emerald City” and the “Harbour City”, Sydney’s allure is multifaceted, drawing residents and visitors alike into its unique sphere.

The historical foundations of Sydney delve deep into Australia’s ancient past, long before European arrival. Archaeological evidence indicates that Aboriginal Australians inhabited the Greater Sydney region at least 30,000 years ago, leaving behind a rich legacy of engravings and cultural sites that remain prevalent today. The traditional custodians of the land where modern Sydney now stands are the distinguished clans of the Darug, Dharawal, and Eora peoples. Their intricate connection to the land, based on a belief system centered on ancestral, totemic, and supernatural beings, fostered rich ceremonial lives, trade, marriages, and clan alliances.

The earliest British settlers documented the term ‘Eora’ as an Aboriginal term denoting either ‘people’ or ‘from this place’, underscoring the deeply ingrained identity associated with the land. The Gadigal (Cadigal) clan, for example, occupied territory along the southern shore of Port Jackson, naming their land Gadi (Cadi). The diversity of Aboriginal clans in the Sydney region, which numbered 28 known groups, each with unique equipment, weapons, body decorations, hairstyles, songs, and dances, vividly illustrates the vibrant Indigenous cultures that flourished there.

The trajectory of Sydney’s history underwent a dramatic transformation with the arrival of Europeans. In 1770, Lieutenant James Cook, during his first Pacific voyage, mapped Australia’s eastern coast, making his initial landfall at Botany Bay, which was known as Kamay to the Gweagal clan he encountered. This initial encounter, characterized by resistance and a Gweagal man being shot and wounded, foreshadowed the profound changes that were to come. Cook’s unsuccessful attempts to forge relations highlighted the cultural divide that would define the ensuing colonial era.

The formal European settlement commenced in 1788 when the First Fleet of convicts, led by Arthur Phillip, arrived. Britain, having lost its American colonies, sought a new penal colony and found Botany Bay suitable, but ultimately selected Port Jackson for its superior harbor. On January 26, 1788, a settlement was established at Sydney Cove, named after Home Secretary Thomas Townshend, 1st Viscount Sydney. Governor Phillip depicted the harbor with remarkable foresight, stating that it was “the finest Harbour in the World… Here a Thousand Sail of the Line may ride in the most perfect Security.”

The nascent colony of New South Wales, which was formally proclaimed on February 7, 1788, faced immediate challenges. Intended to be a self-sufficient penal colony reliant on subsistence agriculture, the poor soil around the settlement resulted in initial crop failures, which precipitated years of hunger and strict rationing. Relief arrived only with the advent of the Second Fleet in mid-1790 and the Third Fleet in 1791. Former convicts were granted land, and farming expanded to more fertile areas, with the colony achieving food self-sufficiency by 1804.

However, the arrival of Europeans also brought about devastating consequences for the Indigenous population. A smallpox epidemic in April 1789 tragically wiped out approximately half of the region’s Indigenous population. Despite this, Aboriginal Australians maintained a continuous presence in the settled area of Sydney, notably when Bennelong led a group of survivors from the Sydney clans into the settlement in November 1790.

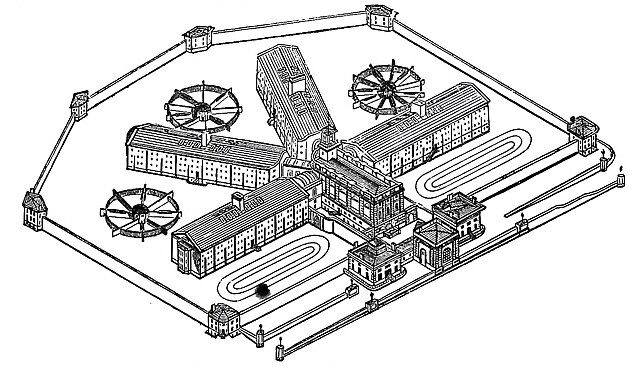

Early urban development in Sydney was largely unplanned. Governor Phillip’s initial plan for Sydney Cove, submitted in July 1788, envisioned a wide central avenue and public buildings but notably lacked provisions for commercial structures. He quickly abandoned his own blueprint, leading to the characteristic unplanned topography of early Sydney. After Governor Phillip, military officers commenced acquiring land and importing goods, while former convicts established businesses, further contributing to the ad hoc development. This lack of centralized control even led to conflicts, culminating in the Rum Rebellion of 1808, when Governor William Bligh was deposed after he attempted to regulate commerce and demolish unauthorized buildings.

The leadership of Governor Lachlan Macquarie (1810 – 1821) marked a pivotal period of development. He played a crucial role in establishing essential institutions such as a bank, a currency, and a hospital. Macquarie commissioned a planner to design Sydney’s street layout and initiated the construction of vital infrastructure, including roads, wharves, churches, and public buildings. The opening of Parramatta Road in 1811 and a road across the Blue Mountains in 1815 were of particular significance, paving the way for large-scale farming and grazing to the west of the Great Dividing Range.

Following Macquarie’s departure, the official policy shifted to encourage free British settlers, which led to a substantial increase in immigration, from 900 free settlers in the period of 1826 – 1830 to 29,000 in the period of 1836 – 1840, many of whom made Sydney their home. By the 1840s, Sydney exhibited a distinct geographic division: working – class residents typically lived to the west of the Tank Stream in areas such as The Rocks, while the more affluent resided to its east. As free settlers, free – born residents, and former convicts constituted the vast majority, public agitation for responsible government and an end to transportation mounted, and transportation to New South Wales was successfully halted in 1840.

The colonial expansion was not devoid of severe conflict. The Castle Hill convict rebellion in 1804 witnessed Irish convicts attempting to march on Sydney, but they were quickly routed, resulting in at least 39 deaths. As the colony expanded into the fertile lands around the Hawkesbury River, conflict with the Darug people intensified from 1794 to 1810. Leaders such as Pemulwuy and his son Tedbury led acts of resistance, burning crops and raiding settler stores. Similarly, in the Nepean region, conflict erupted with the Dharawal people, culminating in the Appin massacre of 1816, in which at least 14 Aboriginal people were killed by military detachments.

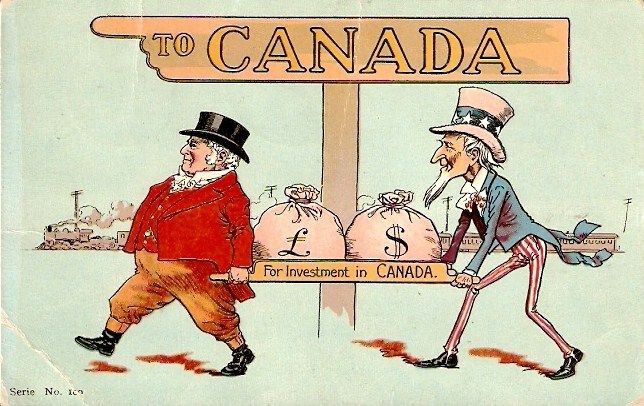

Sydney officially became a city in 1842, the same year when the New South Wales Legislative Council transitioned into a semi – elected body. The discovery of gold in New South Wales and Victoria in 1851 initially caused economic disruption as men flocked to the goldfields. During this period, Melbourne temporarily surpassed Sydney as Australia’s largest city, fostering an enduring rivalry. However, the increased immigration and wealth generated by gold exports fueled the demand for housing, consumer goods, and urban services in Sydney. The New South Wales government further stimulated growth by making heavy investments in railways, trams, roads, ports, telegraph, schools, and urban services.

This era of growth transformed Sydney, with its population and suburbs expanding from 95,600 in 1861 to 386,900 in 1891. The city began to develop its iconic features, with a growing population leading to the construction of rows of terrace houses on narrow streets. New public buildings crafted from sandstone were abundant, including the University of Sydney (1854 – 1861), the Australian Museum (1858 – 1866), the Town Hall (1868 – 1888), and the General Post Office (1866 – 1892). Elaborate coffee palaces and hotels also emerged, contributing to the city’s burgeoning social landscape. Despite these advances, strict social norms prevailed, with daylight bathing at Sydney’s beaches being banned, although segregated ocean baths remained popular.

The late 19th century brought about economic challenges, with drought, a winding – down of public works, and a financial crisis leading to a depression throughout most of the 1890s. Despite this, Sydney – based Premier George Reid played a crucial role in the process of Australian federation.

On January 1, 1901, as the six Australian colonies federated, Sydney officially became the capital of the State of New South Wales. The early 20th century witnessed significant public health and infrastructure reforms; an outbreak of bubonic plague in 1900 prompted the state government to modernize wharves and clear inner – city slums. The First World War (1914 – 1918) absorbed a vast number of Sydney males into the armed forces, effectively reducing unemployment. After the war, returning soldiers were promised “homes fit for heroes” in new suburbs such as Daceyville and Matraville, and “garden suburbs” developed along new rail and tram corridors.

Sydney’s population reached one million in 1926, reclaiming its status as Australia’s most populous city. The government actively created jobs through massive public projects, notably the electrification of the Sydney rail network and the monumental construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Opened in March 1932, the bridge became an enduring symbol of the city’s ambition and engineering prowess. However, this period was also characterized by the Great Depression of the 1930s, which affected Sydney more severely than regional New South Wales or Melbourne. Unemployment soared to 28% among male workers by 1933, exceeding 40% in working – class areas, leading to widespread evictions and the growth of shantytowns like “Happy Valley” at La Perouse.

Political tensions were also high, as exemplified by the dramatic incident at the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932, where Francis de Groot of the far – right New Guard famously upstaged populist Labor Premier Jack Lang by slashing the ribbon. By January 1938, Sydney hosted the Empire Games and celebrated the sesquicentenary of European settlement, which was lauded by journalists for its “Golden beaches. Sun – tanned men and maidens…Red – roofed villas terraced above the blue waters of the harbour.” Yet, this celebration was in stark contrast to the stance of Aboriginal Australians who declared January 26 “A Day of Mourning” for “the whiteman’s seizure of our country.”

Read more about: The Remarkable Journey of Childhood: How Our Understanding of ‘Kids’ Has Made a Brilliant Comeback

World War II spurred significant industrial development in Sydney, virtually eliminating unemployment and enabling women to take on jobs previously dominated by males. The city underwent direct attacks from Japanese submarines in May and June 1942, resulting in 21 fatalities and prompting residents to build air – raid shelters and conduct drills. Military fortifications, including the Garden Island Tunnel System and the Bradleys Head and Middle Head Fortifications, were incorporated into a comprehensive defense system for Sydney Harbour.

The post – war era ushered in a period of rapid population growth, which was fueled by both a baby boom and mass immigration, particularly from Britain and continental Europe. Immigrants and their descendants accounted for over three – quarters of Sydney’s population increase between 1947 and 1971. This growth led to the expansion of low – density housing across the Cumberland Plain, transforming older centers such as Parramatta, Bankstown, and Liverpool into metropolitan suburbs. While manufacturing initially held sway, protected by high tariffs, the long post – war economic boom witnessed retail and other service industries becoming the primary source of new jobs.

In 1954, an estimated one million onlookers, representing most of the city’s population, witnessed Queen Elizabeth II land at Farm Cove, the very spot where Captain Phillip had raised the Union Jack 165 years earlier. This historic event marked the first time a reigning monarch had set foot on Australian soil, highlighting Sydney’s growing prominence.

Increased high – rise development and urban sprawl beyond the “green belt” envisioned by 1950s planners triggered community protests in the early 1970s. Trade unions and resident action groups imposed “green bans” on development projects in historic areas like The Rocks, leading federal, state, and local governments to introduce heritage and environmental legislation. The Sydney Opera House, completed in 1973 despite cost overruns and disputes, quickly became a major tourist attraction and an internationally recognized symbol of the city. From 1974, progressive tariff reductions began to transform Sydney from a manufacturing hub into a “world city.” By 2021, Sydney’s population exceeded 5.2 million, with 40% born overseas, and China and India had surpassed England as the largest source countries for overseas – born residents, highlighting its dynamic and multicultural evolution.

Read more about: Scoop Up Success: How Digital Loyalty Programs Are Revolutionizing Ice Cream Shops for Year-Round Profitability

Sydney’s distinctive geography is pivotal to understanding its unique character. It is situated on a submergent coastline, where rising ocean levels have inundated deep rias, thereby creating its iconic harbor. Bounded by the Tasman Sea to the east, the Blue Mountains to the west, the Hawkesbury River to the north, and the Woronora Plateau to the south, Sydney spans two primary geographic regions. The relatively flat Cumberland Plain lies to the south and west of the Harbour, while the Hornsby Plateau to the north is dramatically dissected by steep valleys. Historically, the flat southern areas were developed first; it was only with the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge that the northern reaches became heavily populated. Along its coastline, Sydney boasts seventy surf beaches, with Bondi Beach being the most renowned.

The city’s hydrological network is equally crucial. The Nepean River winds around the western edge of the city, transitioning into the Hawkesbury River before reaching Broken Bay. Many of Sydney’s water storages are located on the Nepean’s tributaries. The Parramatta River, which is largely industrial, drains a significant portion of Sydney’s western suburbs into Port Jackson. The southern parts of the city are drained by the Georges River and the Cooks River, both of which flow into Botany Bay. Defining Sydney’s boundaries can be complex; the Australian Statistical Geography Standard’s definition of Greater Sydney encompasses a vast area of 12,369 square kilometers (4,776 sq mi), stretching to the Central Coast in the north, Hawkesbury in the north – west, Blue Mountains in the west, Sutherland Shire in the south, and Wollondilly in the south – west. In contrast, the local government area of the City of Sydney covers a mere 26 square kilometers, extending from Garden Island in the east to Bicentennial Park in the west, and south to Alexandria and Rosebery.

Geologically, Sydney is predominantly composed of Triassic rock, interspersed with recent igneous dykes and volcanic necks, notably the Prospect dolerite intrusion west of the city. The Sydney Basin formed in the early Triassic period, with the sandstone that now constitutes much of the city having been laid down between 360 and 200 million years ago, featuring shale lenses and fossil riverbeds. The Australian continental shelf lies a mere 25.9 kilometers (16.1 mi) off Sydney’s coast, marking the edge of the Tasman Abyssal Plain. The Sydney Basin bioregion exhibits coastal features such as cliffs, beaches, and estuaries. Deep river valleys, or rias, carved into the Hawkesbury sandstone during the Triassic period, were subsequently inundated by rising sea levels between 18,000 and 6,000 years ago, creating estuaries and the renowned deep harbors, including Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour). Sydney’s soils generally fall into two main types: sandy soils derived from Hawkesbury sandstone and clay soils from shales and volcanic rocks, although mixtures are common. Overlying the Hawkesbury sandstone in western Sydney is the Wianamatta shale, a Middle Triassic geological feature comprising fine – grained sedimentary rocks such as shales, mudstones, ironstones, siltstones, and laminites, with less common sandstone units.

Sydney’s ecology is characterized by prevalent plant communities such as grassy woodlands (savannas) and pockets of dry sclerophyll forests, dominated by eucalyptus, casuarinas, melaleucas, corymbias, and angophoras, with an understory of shrubs like wattles, callistemons, grevilleas, and banksias, and semi – continuous grass. These plants typically have rough, spiky leaves, adapted to low soil fertility. Wetter, elevated areas in the north and northeast support wet sclerophyll forests, featuring straight, tall tree canopies and moist understories of soft – leaved shrubs, tree ferns, and herbs. Critically endangered vegetation communities such as the Cumberland Plain Woodland in Western Sydney, the Sydney Turpentine – Ironbark Forest in the Inner West and Northern Sydney, the Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub along the coastline, and the scarce Blue Gum High Forest in the North Shore underscore the ecological fragility. The city also includes the Sydney Sandstone Ridgetop Woodland in Ku – ring – gai Chase National Park.

The city abounds with a diverse array of wildlife, encompassing dozens of bird species, such as the Australian raven, Australian magpie, crested pigeon, noisy miner, and pied currawong. Introduced species including the common myna, common starling, house sparrow, and spotted dove are also ubiquitously present. Reptiles, predominantly skinks, are abundant. Mammal species such as the grey – headed flying fox inhabit the region, while the infamous Sydney funnel – web spider, which is actually an arachnid rather than a mammal, also exists in the area. Furthermore, Sydney’s harbor and beaches are home to a vast diversity of marine species, underscoring its rich biodiversity.

Sydney’s climate, classified as a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) under the Köppen–Geiger classification system, is characterized by “warm, sometimes hot” summers and “generally mild” to “cool” winters. This climate is significantly influenced by large – scale atmospheric phenomena, such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, the Indian Ocean Dipole, and the Southern Annular Mode, which govern weather patterns ranging from drought and bushfire to storms and flooding. Proximity to the ocean moderates temperatures, with more extreme temperatures typically recorded in the inland western suburbs, as the Central Business District (CBD) is more strongly affected by oceanic climate drivers.

At Observatory Hill, Sydney’s principal weather station, extreme temperatures have varied significantly, ranging from a record high of 45.8 °C (114.4 °F) on January 18, 2013, to a record low of 2.1 °C (35.8 °F) on June 22, 1932. The CBD experiences an average of 14.9 days per year with temperatures at or above 30 °C (86 °F), while the broader metropolitan area witnesses between 35 and 65 such days, depending on the suburb. The absolute hottest day recorded in the metropolitan area occurred in Penrith on January 4, 2020, reaching a scorching 48.9 °C (120.0 °F). The average annual sea temperature fluctuates from 18.5 °C (65.3 °F) in September to 23.7 °C (74.7 °F) in February, contributing to its generally pleasant conditions. Sydney typically receives 7.2 hours of sunshine per day and has 109.5 clear days annually.

However, due to its inland location, Western Sydney experiences frost on a few occasions during winter mornings. Autumn and spring function as transitional seasons, with spring displaying greater temperature variation than autumn. Sydney also contends with an urban heat island effect, rendering certain areas, including coastal suburbs, more susceptible to extreme heat. Temperatures exceeding 35 °C (95 °F) are common in late spring and summer, often mitigated by a “southerly buster,” a powerful southerly wind that brings gale – force conditions and a rapid temperature drop. Being downwind of the Great Dividing Range, Sydney occasionally encounters dry, westerly foehn winds in winter and early spring, which contribute to warm maximum temperatures. These westerly winds can be particularly intense when the Roaring Forties shift towards southeastern Australia, potentially causing damage and disrupting flights.

Rainfall in Sydney has historically been relatively evenly distributed throughout the year, with moderate to low variability, although recent years have witnessed it becoming more summer – dominant and erratic. Precipitation is generally higher from summer through autumn and lower from late winter to early spring. East – coast lows in late autumn and winter can bring substantial rainfall, particularly to the Central Business District (CBD). In the warm season, “black nor’easters” are often the cause of heavy rain events, along with other low – pressure systems and remnants of ex – cyclones, which can deliver heavy downpours and afternoon thunderstorms. While snow is extremely rare (last reported in 1836, likely graupel), the city has experienced unusual weather events, such as a severe dust storm in 2009, highlighting its vulnerability to diverse climatic phenomena.

Sydney’s urban structure is meticulously planned into a “metropolis of three cities” and five “districts” by the Greater Sydney Commission, encompassing 33 local government areas. These include the Eastern Harbour City, Central River City, and Western Parkland City. The Australian Bureau of Statistics further incorporates the City of Central Coast as part of Greater Sydney for population counts, adding another 330,000 residents to its vast expanse.

The inner suburbs represent the historical and cultural heart of Sydney. The Central Business District (CBD) extends approximately 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) southward from Sydney Cove, bordered by Farm Cove within the Royal Botanic Garden to the east and Darling Harbour to the west. Surrounding the CBD are iconic suburbs such as Woolloomooloo and Potts Point to the east, Surry Hills and Darlinghurst to the south, Pyrmont and Ultimo to the west, and Millers Point and The Rocks to the north. These inner areas, often less than 1 square kilometer in size, are characterized by narrow streets, a legacy of the city’s convict origins.

Key localities within these inner areas serve as vital hubs. Central and Circular Quay function as major transport interchanges for ferries, trains, and buses. Chinatown, Darling Harbour, and Kings Cross are renowned centers for culture, tourism, and recreation. Shopping enthusiasts are attracted to historical landmarks like The Strand Arcade, a Victorian – style arcade that opened in 1892, with shop fronts replicating the original facades, and Westfield Sydney, which is located beneath the Sydney Tower, the city’s largest shopping center in terms of area.

Since the late 20th century, Sydney’s inner suburbs have undergone significant gentrification. Pyrmont, once a hub for shipping and international trade, has been transformed into an area of high – density housing, tourist accommodation, and entertainment. Darlinghurst, historically known for its gaol, manufacturing, and later prostitution, has largely retained its terrace – style housing while experiencing substantial gentrification since the 1980s. Green Square in Waterloo is undergoing an $8 – billion urban renewal project, while the historic suburb and wharves of Millers Point are being redeveloped into the new Barangaroo precinct. Paddington is celebrated for its restored terrace houses, Victoria Barracks, and vibrant shopping, including the weekly Oxford Street markets.

The Inner West region, which comprises the Inner West Council, Municipality of Burwood, Municipality of Strathfield, and City of Canada Bay, extends approximately 11 kilometers west of the CBD. Historically, especially before the construction of the Harbour Bridge, outer Inner West suburbs like Strathfield were home to “country” estates for the colonial elite. In contrast, the inner suburbs of this region, being close to transport and industry, traditionally accommodated working – class industrial laborers. These areas have also experienced gentrification in recent decades, with many now being highly – valued residential suburbs. As of 2021, Strathfield remained one of the 20 most expensive postcodes in Australia in terms of median house price. This area is also an academic powerhouse, housing the prestigious University of Sydney and the University of Technology, Sydney.

Economically, Sydney stands as a global powerhouse. It is classified as an Alpha+ city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network, a designation that signifies its immense influence both regionally and globally. Ranked eleventh worldwide in terms of economic opportunity, Sydney boasts an advanced market economy, with particular strengths in education, finance, manufacturing, and tourism. The city’s educational institutions contribute significantly to its economic vitality; the University of Sydney and the University of New South Wales are globally recognized, ranking 18th and 19th in the world, respectively.

Beyond its economic prowess, Sydney is a cultural and sporting mecca. It has proudly hosted major international sporting events, including the 2000 Summer Olympics, the 2003 Rugby World Cup Final, and the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup Final, thereby cementing its reputation as a premier destination for global events. The city consistently ranks among the top fifteen most – visited cities, attracting millions of tourists annually who are drawn to its iconic landmarks. Sydney’s natural beauty is unparalleled, boasting over 1,000,000 hectares (2,500,000 acres) of nature reserves and parks, with notable features such as Sydney Harbour and the Royal National Park.

Man – made marvels are seamlessly integrated with its natural wonders, with the Sydney Harbour Bridge and the World Heritage – listed Sydney Opera House serving as major tourist attractions and unmistakable symbols of the city. The city’s transportation network is equally impressive, centered around Central Station, which is the hub of Sydney’s suburban train, metro, and light rail networks, as well as longer – distance services. The main passenger airport serving the city is Kingsford Smith Airport, one of the world’s oldest continually operating airports, which further cements Sydney’s connectivity to the global stage.

In essence, Sydney offers a profound case study in urban evolution. From its ancient Indigenous roots to its colonial past, through periods of conflict, gold rushes, and global wars, to its current status as a vibrant, multicultural Alpha+ city, Sydney consistently demonstrates an extraordinary capacity for transformation. It is a city that not only excels economically and culturally but also embraces its unique geographical and ecological footprint. For anyone seeking to understand the complexities and triumphs of a truly global city, Sydney presents a compelling narrative of resilience, innovation, and enduring charm.