The White House, a symbol of American democracy, has long been a place where history is made, policies are debated, and the fate of the nation is shaped. Yet, behind the scenes of monumental decisions and diplomatic gatherings, the kitchens of the Executive Mansion have always hummed with activity. These culinary spaces reflect the personal tastes, cultural backgrounds, and even the political strategies of its distinguished residents. From simple comfort foods cherished during times of hardship to elegant dishes prepared for foreign dignitaries, the culinary preferences of America’s presidents and first ladies offer a fascinating, often surprising, window into their lives and times.

Food has a unique power to tell a story, connecting us to the past and revealing the human side of even the most formidable figures. In this extensive culinary journey, we’re diving deep into some of the most famous and intriguing recipes and food preferences that have graced the tables of the White House. These are not just recipes; they are historical artifacts, each bite a taste of the past. They offer insights into personalities, regional influences, and the evolution of American dining. Get ready to explore a rich tapestry of flavors, techniques, and traditions that have nourished and delighted our nation’s first families.

Join us as we uncover 14 iconic dishes, meticulously crafted or passionately consumed by presidents and first ladies, inviting you to step into their kitchens and perhaps even recreate a piece of American culinary heritage in your own home. Our first seven selections delve into some of the earliest and most intricate recipes, offering a glimpse into the sophisticated and sometimes elaborate cooking prevalent in the nascent stages of the republic and beyond. Each recipe tells a tale, blending historical context with practical culinary artistry, proving that flavor and heritage are deeply intertwined in the heart of the White House.

1. **Martha Washington’s Recipe for Black Great Cake**Imagine the grandeur of Martha Washington’s Mount Vernon kitchen, where lavish preparations for entertaining were commonplace. Among the most impressive was her legendary Black Great Cake, a dessert that truly lived up to its name, signifying both its size and the richness of its ingredients. This wasn’t merely a cake; it was a statement piece, a testament to the abundance and hospitality of the Washington household. It reflected the nascent nation’s desire to project an image of prosperity and sophistication.

The recipe itself is a delightful glimpse into 18th-century baking, calling for an astounding 40 eggs, carefully separated into whites and yolks, each beaten to a froth. This task would have required considerable effort and time from the kitchen staff. This intricate preparation highlights the dedication to culinary excellence that defined the First Lady’s approach to managing her household. Such a grand undertaking suggests the cake was reserved for significant occasions, perhaps state dinners or important celebrations, symbolizing the celebratory spirit of the era.

Beyond the eggs, the recipe dictates working “4 pounds of butter to a cream,” followed by an equal amount of “sugar finely powdered,” gradually incorporating the egg whites and then the yolks. This meticulous creaming method was essential for achieving a light yet rich texture, a hallmark of fine baking even today. The inclusion of “5 pounds of flour and 5 pounds of fruit” speaks to the cake’s substantial nature. It promised a dense, flavorful crumb packed with dried fruits that would have been a luxury and a testament to the household’s resources.

To further elevate its profile, the cake was seasoned with “half an ounce of mace and nutmeg,” warm spices that added depth and aromatic complexity. A generous “half a pint of wine and some fresh brandy” were also added. These additions were not just for flavor but likely for preservation, given the cake’s size and the lack of modern refrigeration. These ingredients would have contributed to a truly decadent and multi-layered taste profile, fitting for a presidential table.

The original baking time noted, “2 hours will bake it,” followed by a striking correction, “Five and a half hours will bake it.” This indicates the careful attention to detail and perhaps the challenges of early oven technology required to achieve perfection for such a monumental confection. This significant adjustment underscores the artisanal nature of baking in that era, where success often hinged on keen observation and experience. Martha Washington’s Black Great Cake remains a powerful symbol of early American culinary ambition, a grand dessert for a grand new nation.

2. **Nelly Custis Lewis’ Recipe for Hoecakes**While Martha Washington’s Black Great Cake might represent the grandeur of the early republic, Nelly Custis Lewis, Martha Washington’s youngest granddaughter, offers us a recipe for a far more rustic yet equally beloved dish: hoecakes. These simple cornmeal pancakes were a staple of early American cuisine, especially in the South. They reflected the practical and resourceful nature of colonial kitchens. Nelly’s letter provides a charming, personal insight into their preparation.

The instructions begin the night before, taking “one quart of flour, five table spoonfuls of yeast & as much lukewarm water as will make it the consistency of pancake batter.” This initial mixture, referred to as a “sponge,” was to be “mix it in a large stone pot & set it near a warm hearth (or a moderate fire).” This allowed it to ferment overnight. This method, common for leavened breads, created a deep, rich flavor and a tender texture, a testament to traditional baking wisdom.

The next morning, the process continues with the gradual addition of “the remaining quart & a half” of flour, carefully mixed in with a spoon. After a short rest of “15 or 20 minutes,” the dough is ready to be transformed. The recipe then describes beating “up a white & half of the yilk of an egg” with “as much lukewarm water as will make it like pancake batter.” This mixture is then dropped “a spoonful at a time on a hoe or griddle (as we say in the south).”

The term “hoecake” itself evokes images of early American outdoor cooking. These flatbreads were traditionally cooked on a hot hoe blade over an open fire. Nelly’s mention of a “griddle (as we say in the south)” suggests a transition to more conventional kitchen equipment, though the spirit of simplicity remained. When done on one side, they are to be turned. This ensures even cooking and a golden-brown finish.

The final instruction highlights the importance of seasoning the cooking surface for a perfect, non-stick result and adding a subtle richness to the finished hoecakes. The “griddle must be rubbed in the first instance with a piece of beef suet or the fat of cold corned beef.” These simple, hearty cakes were a cornerstone of George Washington’s own diet, often served at Mount Vernon with honey or molasses, embodying the down-to-earth nature of early American cuisine.

3. **Martha Jefferson Randolph’s Macaroni**Thomas Jefferson’s daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, presided over a household that, like her father’s, was deeply influenced by European culinary trends, particularly those from France and Italy. Her recipe for Macaroni showcases an early American interpretation of a dish that would later become an enduring comfort food classic. This recipe is a fascinating example of how foreign dishes were adapted and integrated into the American culinary landscape, bringing new flavors to the presidential table.

The directions are wonderfully straightforward, beginning with “Boil as much macaroni as will fill your dish, in milk and water, till quite tender.” The choice to boil pasta in a mixture of milk and water, rather than just water, is particularly interesting. It suggests an attempt to imbue the pasta with a creamy richness from the very start. This method would have resulted in a softer, more luxurious noodle, subtly infused with dairy notes, a precursor to modern gourmet pasta preparations.

Once tender, the macaroni is drained “on a sieve” and sprinkled with “a little salt,” a crucial step for seasoning and enhancing the pasta’s inherent flavor. The next phase introduces layers: “put a layer in your dish then cheese and butter as in the polenta, and bike it in the same manner.” The reference to polenta implies a layering technique familiar to those conversant with Italian cooking. Cheese and butter are generously interspersed with the main ingredient. This approach transforms simple boiled pasta into a rich, baked casserole, much like a gratin.

This early American macaroni dish, a precursor to the beloved macaroni and cheese, illustrates a nascent culinary sophistication in the Jeffersonian era. It speaks to a desire for varied and flavorful meals, even if the ingredients and techniques were still evolving on American soil. The inclusion of such a dish demonstrates an adventurous palate and a willingness to embrace international flavors, a reflection of Thomas Jefferson’s own global outlook.

Martha Jefferson Randolph’s kitchen was clearly a place of culinary experimentation and adaptation, bringing a taste of the Old World to the New, transforming humble ingredients into something special. She also shared recipes for other intriguing dishes like “Chicken Pudding, a Favorite Virginia Dish,” which further highlights the diversity and regional influences in her culinary repertoire. Her contributions offer valuable insights into the dining habits of the early American elite.

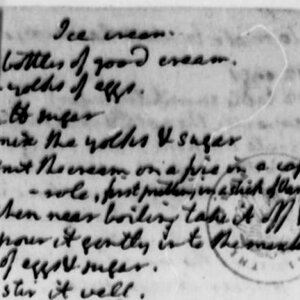

4. **Thomas Jefferson’s Ice Cream Recipe**Few figures in American history are as closely associated with a single food item as Thomas Jefferson is with ice cream. Having developed a profound appreciation for French cuisine during his time as minister to France, Jefferson brought a love for exotic foods and culinary innovation back to America. His handwritten ice cream recipe, preserved in the Library of Congress, is not just a historical document but a testament to his absolute obsession with this frozen delicacy, which he served regularly at presidential dinners.

The recipe begins with the luxurious base of “2 bottles of good cream” combined with “6 yolks of eggs” and “1/2 lb. sugar.” This rich custard mixture is carefully prepared. The yolks and sugar are mixed, while the cream is heated in a casserole with a “stick of Vanilla” until “near boiling.” The hot cream is then “gently” poured into the egg and sugar mixture, stirring “well” to temper the eggs and prevent curdling, a fundamental technique in custard making.

The mixture is then returned to “the fire again stirring it thoroughly with a spoon to prevent it’s sticking to the casserole,” until “near boiling” once more, after which it is strained “thro’ a towel.” This straining ensures a perfectly smooth custard, free of any small lumps or impurities. The real magic, however, happens next, as the custard is placed “in the Sabottiere*,” which is Jefferson’s term for a cylindrical metal container used for freezing.

The Sabotiere is then set “in ice an hour before it is to be served,” with “a handful of salt” added to the ice, and “salt on the coverlid of the Sabotiere & cover the whole with ice.” The salt dramatically lowers the freezing point of the ice, allowing the cream to freeze more efficiently and effectively. The process involves periods of stillness and then turning “the Sabottiere in the ice 10 minutes.” The Sabotiere is then opened “to loosen with a spatula the ice from the inner sides of the Sabotiere,” and stirred “well with the Spatula” when “well taken (prise).”

This detailed method showcases a sophisticated understanding of ice cream production, remarkable for its time, culminating in placing the ice cream “in moulds, justling it well down on the knee” and then back into the ice until serving. To serve, the mold is immersed in warm water “turning it well till it will come out & turn it into a plate.” Jefferson’s dedication to this treat cemented his legacy as America’s unofficial ice cream founding father, and his recipe remains a fascinating piece of culinary history.

Thomas Jefferson’s Ice Cream Recipe

Ingredients

Equipment

Method

- Split the vanilla stick lengthwise and scrape out the seeds. In a saucepan, combine the cream, vanilla seeds, and the scraped pod.

- Heat the cream mixture over medium heat until it simmers gently around the edges, then remove from heat.

- In a separate mixing bowl, whisk together the egg yolks and sugar until the mixture is pale and creamy.

- Slowly ladle about one cup of the hot cream mixture into the egg yolk mixture, whisking continuously to temper the yolks and prevent scrambling.

- Pour the tempered egg mixture back into the saucepan with the remaining cream. Return the saucepan to low heat.

- Cook, stirring constantly with a whisk or wooden spoon, until the custard thickens enough to coat the back of a spoon (reaching approximately 170-175°F or 77-79°C). Do not boil.

- Remove the custard from heat, stir in a pinch of salt, and strain it through a fine-mesh sieve into a clean bowl to ensure a silky-smooth texture, discarding the vanilla pod.

- Place the bowl over an ice bath or cover tightly and refrigerate until the custard is thoroughly chilled, at least 4 hours or preferably overnight.

- Once completely chilled, churn the mixture in an ice cream maker according to the manufacturer’s instructions until it reaches a soft-serve consistency.

- Transfer the ice cream to an airtight container and freeze for at least 2-4 hours to allow it to firm up before serving.

Notes

5. **Lucy Web Hayes’ Oysters Stew**Moving forward in time to the Hayes Administration (1877-1881), we encounter new culinary delights, one of which is Lucy Web Hayes’ appealing Oysters Stew. This recipe speaks volumes about a popular American fondness for shellfish, a taste avidly shared by President Hayes himself, who was celebrated as an “avid oyster-lover.” It’s a dish that artfully combines the briny freshness of the sea with the comforting richness of cream. It was perfectly suited for a light yet satisfying meal that was a staple of the era.

The preparation begins with placing “a quart of oysters on the fire in their own liquor.” Cooking oysters in their natural juices is a key technique, essential for preserving their delicate flavor and ensuring they don’t become tough or rubbery. The precise instruction to “skim them out” the moment they “begin to boil” highlights a crucial step to prevent overcooking, ensuring the oysters remain plump and tender. This is a mark of a skilled hand in the kitchen and an appreciation for seafood’s subtle nuances.

The reserved liquor forms the foundational broth for the stew, to which “a half-pint of hot cream, salt, and cayenne pepper to taste” are added. The careful balance of creamy richness with a subtle kick of spice promises a harmonious flavor profile, designed to complement rather than overpower the inherent briny essence of the oysters. Skimming the mixture “well” ensures a clean, smooth broth, indicative of the care put into both presentation and the overall texture of the stew, creating a truly inviting dish.

Finally, the stew is taken “off the fire,” and “an ounce and a half of butter broken into small pieces” is added directly to the oysters. This finishing touch of butter, incorporated right before serving, provides a luscious sheen and extra depth of flavor, melting into the warm shellfish. It elevates the dish from simple fare to something more indulgent, showcasing a common culinary practice of the late 19th century.

The directive to “Serve immediately” emphasizes the importance of enjoying the stew at its absolute peak, ensuring the best possible texture and flavor. This fresh and comforting dish perfectly encapsulates a taste of late 19th-century American dining, loved by a president and his family. Beyond the oysters, Lucy Web Hayes also had a recipe for Corn Bread, further demonstrating her practical versatility in the White House kitchen and her ability to cater to a range of tastes, from elegant seafood to rustic staples.

6. **Henrietta Nesbitt’s Gumbo Z’Herbes (Cheapest Soup)**During the Franklin Roosevelt Administration (1933-1945), the White House kitchen was overseen by Henrietta Nesbitt, whose recipes often reflected a practical approach, sometimes shaped by the economic realities of the Great Depression. Her Gumbo Z’Herbes, also known as “Cheapest Soup,” is a remarkable example of resourceful cooking. It transforms humble greens into a flavorful and hearty dish. This recipe speaks to a time when making the most of available ingredients was not just economical but a culinary art form.

The ingredient list itself is a vibrant tapestry of greens: “1 bunch each of spinach, mustard greens, green cabbage, beet tops, watercress, radishes, chopped onion, parsley, thyme, bay leaf, green onion top, salt, pepper, red pepper pod or drop of Tabasco.” This medley of vegetables, often readily available or grown in home gardens, forms the nutritional core of the soup. The addition of “Bacon strip, veal or port brisket, or hambone” provides a foundational savory depth. It illustrates how even a small amount of meat could flavor a large pot.

The preparation starts with washing the greens and meat thoroughly, followed by boiling them in hot water. Crucially, the water is “Drain off… and save it,” recognizing its value as a flavorful stock. The meat is then fried “in one tablespoon lard,” and “chopping up the while with the greens with the onion and seasoning” before removing the meat. This step builds layers of flavor, caramelizing the meat and vegetables to develop a rich base.

The greens are then fried until “well fried,” followed by the addition of “all the flour, stir” to create a roux, a classic thickening agent for gumbo. This roux provides both body and a nutty flavor, essential for the authentic taste and texture of a traditional gumbo. After seasoning “well,” the meat is returned, and “the treasured water of the boiled greens” is added.

The mixture is left to “simmer for an hour or so,” allowing all the flavors to meld and deepen into a rich, complex gumbo. This dish is a true testament to making something extraordinary from simple means during challenging times. Nesbitt’s emphasis on utilizing readily available ingredients, as seen in her recipes for Croquettes and Lismore Stew, highlights her thrifty and practical approach to White House menus.

7. **Dwight Eisenhower’s Recipe for Green Turtle Soup**While President Eisenhower was famously known for his hearty beef stew, his recipe for Green Turtle Soup showcases a surprisingly exotic and elaborate side of his culinary repertoire. This dish is a stark contrast to the simplicity of some other presidential favorites. It demands a meticulous and somewhat challenging preparation, indicative of a taste for sophisticated and perhaps adventurous dining experiences during his administration.

The recipe begins with a very specific and dramatic instruction: “Cut off the head from a live green turtle and drain the blood.” This immediately signals the traditional, from-scratch nature of the dish, emphasizing a culinary practice that is largely obsolete today. Following this, the “four flappers” are removed, and the “back and the belly” are divided into four parts. The entire ensemble, “without the intestines,” is then blanched in boiling water “for about three minutes” to prepare it for skinning.

After blanching, the skin is removed “with a coarse cloth” while the pieces are still warm. The pieces are then to be “wash the pieces well and lay them in clean water with a sufficient amount of mixed vegetables, bay leaves, thyme, a little garlic, lemon skin, parsley, and season with salt and pepper.” This initial simmering, lasting “from two and a half to three hours,” extracts the foundational flavors of the turtle and aromatics, forming a rich broth.

The broth is then strained, and the turtle meat is cut “into small cube-sized pieces and place in a pot, covered with sherry,” adding a layer of flavor and tenderization. The strained broth undergoes a clarifying process, combined with “chopped beef, fresh mixed vegetables, whites of eggs, bay leaves, garlic, cloves, parsley; season with salt and pepper and cook this again for three hours.” The egg whites, along with the chopped beef, form a raft that clarifies the broth, ensuring a perfectly clear and refined soup, a hallmark of haute cuisine.

Finally, the broth is strained again “with a cheesecloth,” and kept hot. To achieve “a more delicate and more spicy flavor,” sherry wine infused with various herbs and peppers is prepared, heated, strained, and then added to the soup before serving, allowing for a personalized touch. This complex recipe reveals a deep dive into historical culinary practices and a refined palate at the Eisenhower White House, reflecting a truly dedicated approach to gourmet cooking.

As we continue our delectable journey through the White House kitchens, we move from foundational recipes to the personal comfort foods and defining tastes that shaped later presidencies. This section illuminates how American culinary preferences evolved, reflecting a blend of regional traditions, personal quirks, and an increasing appreciation for both sophisticated and universally beloved dishes. From sweet treats that offered solace during trying times to elegant European-inspired desserts and hearty American staples, these selections offer yet another fascinating glimpse into the lives of our nation’s leaders and their families, proving that every dish tells a story.

Get ready to explore these iconic flavors and the moments they created, as we uncover the recipes and food preferences that truly defined their eras. These are the dishes that brought comfort, fostered diplomacy, and reflected the very essence of the individuals who called the White House home. Prepare to be inspired by the culinary tapestry woven through the fabric of American history, from humble ingredients transformed into heartwarming meals to gourmet delights served to royalty.

8. **Abraham Lincoln’s Gingerbread Men**President Abraham Lincoln, the sixteenth president, was known for his towering presence and profound leadership, but he also harbored a delightful secret: a notorious sweet tooth. This particular fondness was happily indulged by his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, who often baked batches of gingerbread men, a simple yet comforting treat that provided a moment of sweetness amidst the immense pressures of leading a nation during the Civil War. Imagine the White House kitchen, filled with the warm, spicy aroma of freshly baked gingerbread, a comforting antidote to the somber political climate.

These gingerbread men were more than just a dessert; they were a source of personal solace for Lincoln. He would often reach for them during stressful Cabinet meetings, finding a brief respite in their familiar taste and playful shape. The story goes that he would playfully bite off their heads first, a quirky habit that offered a momentary, lighthearted escape from the heavy burdens he carried. Such a simple act underscores how food can provide profound comfort and a touch of humanity during America’s darkest hours, a testament to its power beyond mere sustenance.

While a precise historical recipe for Mary Todd Lincoln’s gingerbread men isn’t fully detailed, the essence lies in their warm, aromatic spices—ginger, cinnamon, and cloves—combined with molasses for a distinctive, deep flavor. The magic of gingerbread is in its ability to evoke nostalgia and warmth, making it the perfect treat to offer a moment of peace. Recreating these cookies today means embracing that same spirit of homely comfort, ensuring a tender, chewy texture with just the right snap, making them as beloved now as they were in Lincoln’s day.

9. **Dwight Eisenhower’s Beef Stew**General-turned-President Dwight D. Eisenhower, renowned for his military strategy and calm demeanor, possessed another skill that endeared him to family and friends: his culinary prowess, particularly his hearty beef stew. While we explored his more elaborate Green Turtle Soup in the previous section, it was this rustic, comforting stew that truly showcased his practical, nurturing approach. Eisenhower took immense pride in his cooking, often preparing this signature dish personally, transforming the White House kitchen into his personal domain of flavorful creation.

This wasn’t just any beef stew; it was a testament to robust, satisfying American home cooking. Mamie Eisenhower, his devoted wife, actively encouraged her husband’s cooking hobby, understanding that it offered him a vital outlet for relaxation and creative expression away from the demanding responsibilities of the presidency. The act of meticulously browning meat, chopping vegetables, and simmering a pot slowly over hours was a meditative process for the leader, allowing him to unwind and connect with his loved ones through the universal language of food.

Eisenhower’s recipe was known for its generous amounts of wholesome vegetables—carrots, potatoes, and onions—combined with tender, slow-cooked beef, all bathed in a rich, savory broth. The simplicity of the ingredients belied the depth of flavor achieved through patient preparation. It reflected his down-to-earth Missouri roots and a belief in hearty, sustaining meals that nourished both body and soul. This beef stew wasn’t merely a meal; it was a symbol of strength, comfort, and the enduring values of American home life, a true presidential classic.

10. **John F. Kennedy’s Favorite Boston Clam Chowder**When John F. Kennedy, the youngest elected president, moved into the White House, he brought with him not just a youthful vigor but also a deep appreciation for his New England heritage, prominently displayed through his unwavering love for Boston Clam Chowder. This iconic dish became a staple on White House menus, reflecting his personal taste and connecting him to his Massachusetts roots, even as he hosted world leaders and dignitaries. Kennedy famously insisted on the authentic Boston version, creamy and rich, emphatically rejecting any suggestion of the tomato-based Manhattan style.

To prepare this classic, begin by thoroughly scrubbing two pounds of little neck clams under cold running water to remove any impurities. Place them in a large, deep saucepan with just enough water to cover, bringing them to a boil for about five minutes until their shells elegantly open. This crucial step ensures tender, perfectly cooked clams while yielding a flavorful broth. Strain this precious broth through a fine mesh sieve, reserving it, and then carefully remove the clams from their shells, chopping the succulent flesh into half-inch pieces, ready for their starring role.

In a separate large saucepan, melt a tablespoon of butter over medium heat, then add an ounce of cubed salt pork or bacon. Cook, stirring often, for two to three minutes until it becomes beautifully translucent, rendering out its rich flavor. Next, add a finely chopped onion, cooking and stirring occasionally for about ten minutes until it softens and becomes translucent, but not browned. This careful browning builds a foundational layer of aromatic flavor for the chowder.

Now, introduce two peeled and diced potatoes, approximately one pound, cooking them for just one minute before pouring in the reserved clam broth. Bring the mixture to a boil and let it simmer for about eight minutes, or until the potatoes are delightfully fork-tender. This ensures a creamy texture without overcooking the main components. Finally, add the chopped clams, half a teaspoon each of salt and pepper, and cook for just one minute more until the clams are heated through, preserving their delicate texture.

Remove the chowder from the heat immediately, then stir in one cup of warm milk and three-quarters cup of warm whipping cream. The warmth of the dairy is key to preventing curdling and achieving that signature velvety consistency that defines a perfect Boston Clam Chowder. Serve this magnificent, creamy soup immediately, allowing the rich flavors of the sea, the hearty potatoes, and the luscious cream to shine. A thoughtful tip from the White House kitchen: if you need to reheat, do so gently, never allowing it to boil, to maintain its exquisite texture and taste. This dish isn’t just food; it’s a taste of history, connecting you directly to the New England heritage that so deeply shaped a president.

Read more about: Unveiling the Presidential Palate: 13 Intriguing Details About John F. Kennedy’s Favorite Foods

11. **Chef René Verdon’s Strawberries Romanoff**In a departure from hearty stews and traditional American fare, the Kennedy White House also embraced sophisticated European elegance, beautifully exemplified by Chef René Verdon’s Strawberries Romanoff. This exquisite dessert graced a luncheon with Princess Grace, perfectly showcasing the blend of American vitality and international refinement that characterized the Kennedy administration. It’s a delightful, airy concoction, where fresh strawberries meet a cloud of whipped cream and softened ice cream, all kissed with the vibrant notes of orange liqueur.

To begin this elegant creation, retrieve one cup of vanilla ice cream from the freezer and place it in the refrigerator for about 30 minutes. This allows it to soften just enough to be easily smoothed with the back of a spoon, achieving a supple, pliable texture essential for later mixing. Simultaneously, prepare four cups of small strawberries, halving them if they’re not already petite. Place these glistening berries into a large bowl, ready for their flavor infusion.

Next, pour two tablespoons each of curacao and Grand Marnier, or your preferred orange-flavored liqueur, over the waiting strawberries. Stir them gently to ensure each berry is coated in the fragrant spirits, then let them stand for 30 minutes. This marinating period allows the strawberries to absorb the liqueurs, deepening their flavor and adding a sophisticated warmth that elevates their natural sweetness. The anticipation builds as the berries transform.

Now, for the creamy heart of the dessert: in a large, well-chilled bowl, use an electric mixer to beat half a cup of whipping cream at low speed. Continue for about 45 seconds until it begins to slightly thicken. Then, add one tablespoon of confectioner’s sugar and half a teaspoon of pure vanilla extract, increasing the speed to medium-high. Beat for a full three minutes, or until the cream becomes luxuriously thick and holds soft peaks, a testament to perfect whipping technique.

Return to your softened ice cream and stir it with a wooden spoon in its large bowl until it’s beautifully smooth. With a rubber spatula, gently fold a dollop of the freshly whipped cream into the softened ice cream. This initial incorporation lightens the ice cream without deflating the cream. Add the remaining whipped cream and continue to fold gently until the two components are well combined, creating a delicate, ethereal mixture that is both rich and surprisingly light.

To serve this masterpiece, spoon enough of the liqueur-infused strawberries into the bottom of chilled glass dessert bowls to just cover the base. Top this vibrant layer with a generous dollop of the airy cream mixture. Then, divide the remaining berries and any delicious juices among the bowls, ensuring everyone gets a fair share of the fruit’s brightness. Finally, distribute the remaining cream equally, creating a visually stunning presentation. A final flourish: garnish each dish with delicate candied violets or fresh mint leaves, adding both beauty and an extra hint of flavor. Serve immediately to capture its peak freshness and chilled perfection. For larger strawberries, a quick cut into quarters ensures even distribution, and those exquisite candied violets can often be found at upscale grocers, making this a dessert fit for royalty and beloved by a nation.

12. **Lyndon Johnson’s Barbecue**When Lyndon B. Johnson took office, he didn’t just bring his political agenda to Washington; he brought the expansive, robust flavors of Texas barbecue. LBJ was famous for his Texas-sized appetites, and he often transformed the White House lawn into a casual, yet politically significant, cookout. His favorite was undoubtedly slow-smoked brisket, served with a tangy, distinctive sauce that spoke of the deep culinary traditions of his home state. This wasn’t just food; it was a cultural statement, a piece of Texas shared with the nation and the world.

Lady Bird Johnson, with her characteristic grace, wholeheartedly supported these casual gatherings. She understood that these barbecue events were more than just social occasions; they were a vital component of her husband’s “barbecue diplomacy.” Foreign leaders, often accustomed to formal state dinners, were treated to a uniquely American experience, savoring true comfort food while engaging in critical discussions. The scent of wood smoke and savory meats wafting across the White House grounds became synonymous with LBJ’s approachable yet formidable leadership style.

While the full, intricate details of LBJ’s specific brisket recipe are likely guarded family secrets of pitmasters, the essence of it lies in the low-and-slow smoking process, which transforms tough cuts of beef into incredibly tender, flavorful masterpieces. The “tangy sauce” would have been a crucial element, balancing the richness of the meat with bright, zesty notes, often featuring vinegar, spices, and a touch of sweetness. Recreating this experience involves patience, a good smoker, and a commitment to flavor, allowing everyone to taste a piece of Texas history, deeply embedded in the legacy of a president who knew how to connect through cuisine.

13. **Pat Nixon’s Meat Loaf**Moving into the Nixon administration, we find another comforting, quintessentially American dish that held a special place at the presidential table: Pat Nixon’s Meat Loaf. This humble yet beloved meal was a firm favorite of President Richard Nixon, so much so that it made a regular appearance on the White House menu, served approximately once a month. It reflects a desire for familiarity and simple comforts, even amidst the complexities of national and international affairs, showcasing that presidents, too, yearn for the taste of home.

Pat Nixon’s version of this classic dish was noted for its specific components: ground beef, often a mix of lean and richer cuts for flavor, combined with white bread, serving as a binder to keep the loaf moist and tender. A touch of marjoram, an aromatic herb, was also included, adding a subtle, savory depth that elevated the flavor profile beyond the ordinary. This thoughtful selection of ingredients speaks to a practical yet discerning approach to everyday cooking, where seemingly small choices can make a significant difference in taste and texture.

The beauty of a well-made meat loaf, like Pat Nixon’s, lies in its ability to be both satisfyingly hearty and remarkably versatile. It’s a dish that embodies the warmth of family dinners and the comfort of tradition. Whether served with mashed potatoes, green beans, or a simple side salad, it creates a meal that is both nourishing and deeply nostalgic. Her recipe, simple in its construction but rich in flavor, reminds us that even presidents find solace in the familiar and comforting dishes prepared by those they love.

14. **Hillary Rodham Clinton’s Lamb**Bringing our culinary journey closer to the modern era, the Clinton administration introduced a blend of traditional American cuisine with a burgeoning appreciation for global flavors and healthy eating, a vision championed by First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton. It’s no surprise that when the Clintons’ White House chef was interviewed for the coveted position, he wisely prepared Hillary’s favorite meat: lamb. This strategic culinary choice not only sealed his job but also highlighted the First Lady’s personal palate and her forward-thinking approach to White House dining.

Hillary Clinton was known for her excitement regarding the culinary scene within the White House. She actively advocated for a diverse menu that harmoniously blended classic American dishes with international cuisine, reflecting a more globalized worldview. This commitment extended to promoting healthier eating habits, ensuring that elegance and flavor didn’t come at the expense of well-being. Her preference for lamb speaks to a refined taste, enjoying a protein that is both versatile and rich in flavor, adaptable to various preparations from traditional roasts to globally inspired presentations.

While a specific recipe for Hillary Clinton’s lamb isn’t detailed, the context suggests a sophisticated approach to its preparation, likely emphasizing fresh ingredients and perhaps lighter, more contemporary cooking methods. Whether it was a perfectly roasted rack of lamb, savory lamb chops with herbs, or a more adventurous lamb tagine, the presence of lamb on the White House menu under her influence symbolized a blend of personal preference, evolving culinary trends, and a dedication to a diverse and healthy dining experience for the nation’s first family and their guests. It marks a significant shift, showcasing how presidential palates continued to evolve, integrating global influences into the fabric of American culinary identity.

What an incredible journey we’ve embarked upon, tasting our way through centuries of White House history! From Martha Washington’s monumental Black Great Cake, a symbol of a nascent nation’s aspirations, to Hillary Clinton’s embrace of global lamb dishes, each recipe and culinary preference offers a unique window into the personal lives and broader cultural contexts of America’s most prominent figures. These are more than just ingredients and instructions; they are stories, traditions, and glimpses into the human side of leadership, proving that food truly is a universal language, capable of revealing character, comforting souls, and even shaping diplomacy. We hope you’ve savored every historical bite and perhaps found some inspiration to bring a piece of presidential culinary heritage into your own kitchen!