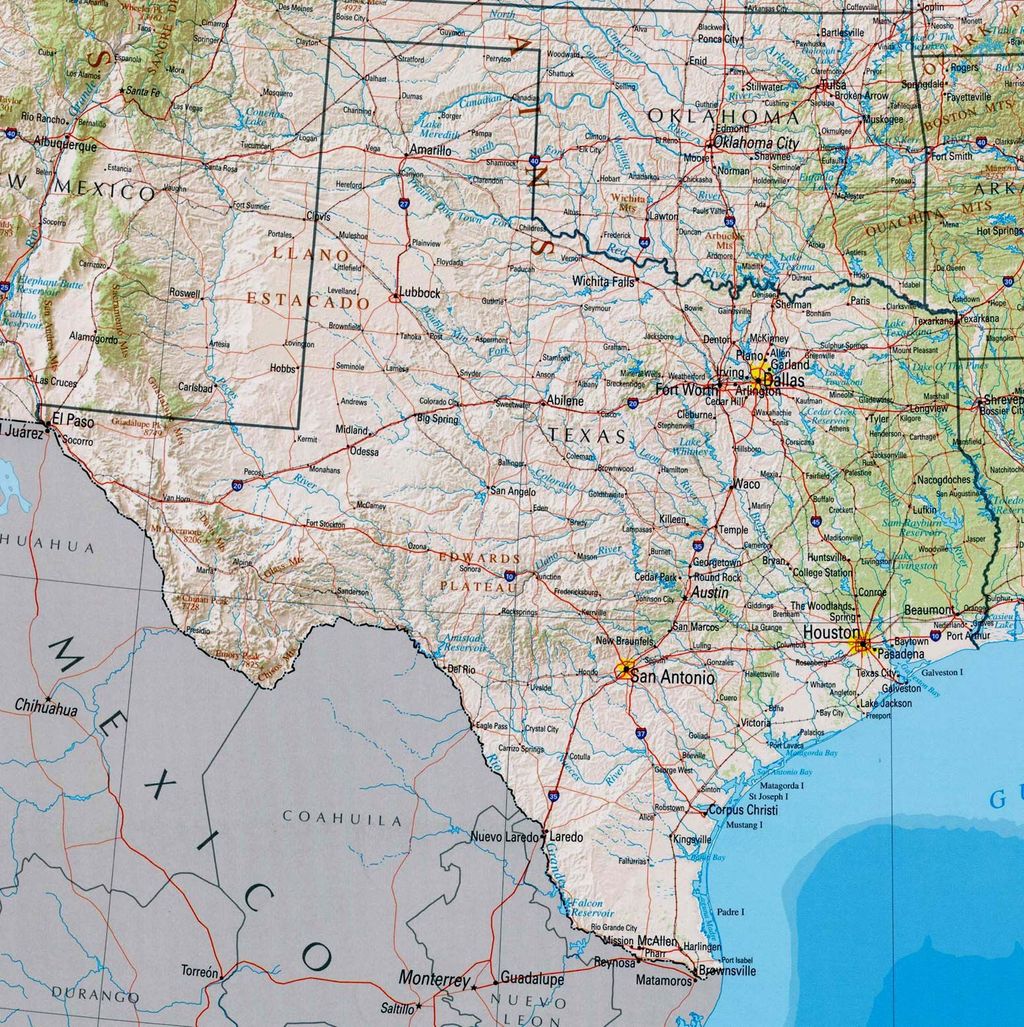

Texas, a name derived from the Caddo word táy:shaʼ, meaning ‘friend,’ stands as a colossal and ever-evolving entity within the United States. Covering an expansive 268,596 square miles (695,660 km2) and boasting over 31 million residents as of 2024, it holds the distinction of being the second-largest state by both area and population. This immense scale, coupled with a history steeped in diverse influences and transformative shifts, contributes to a political landscape as dynamic and multifaceted as its terrain.

From the coastal swamps and piney woods of the east to the rolling plains, rugged hills, desert, and mountains of the Big Bend in the west, Texas encompasses an extraordinary range of environments. Such geographical diversity, encompassing ten climatic regions, fourteen soil regions, and eleven distinct ecological regions, makes any simple categorization of the state into a single U.S. region a challenging endeavor. It can simultaneously be perceived as an extension of the Deep South in its eastern reaches and unequivocally part of the interior Southwest in its far western territories.

This vastness is further accentuated by its intricate natural borders, including the Rio Grande to the south with Mexican states, the Red River to the north with Oklahoma and Arkansas, and the Sabine River to the east with Louisiana. The state’s geography also features 3,700 named streams and fifteen major rivers, notably the Rio Grande, Pecos, Brazos, Colorado, and Red River. While natural lakes are scarce, Texans have ingeniously constructed over a hundred artificial reservoirs, demonstrating an enduring capacity to shape their environment.

Texas’s deep historical roots precede European arrival, positioned between the major cultural spheres of Pre-Columbian North America: the Southwestern and Plains areas. Archaeologists have identified three dominant Indigenous cultures—the Ancestral Puebloans, the Mississippian culture, and the civilizations of Mesoamerica—that reached their peak development here. A diverse array of languages, including Caddoan, Atakapan, Athabaskan, Coahuiltecan, and Uto-Aztecan, were spoken by the native peoples who inhabited the region, shaping the earliest human interactions with this land.

European engagement began with Spanish claims, followed by a brief French colonial presence. The first historical document related to Texas was a map of the Gulf Coast created in 1519 by Spanish explorer Alonso Álvarez de Pineda, and shipwrecked explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca became one of the first Europeans in what is now Texas in 1528. Spanish authorities, concerned by French competitive threats, established missions among the Caddo, but sustained European settlement was challenged by hostile native tribes and distance from existing colonies.

Mexico gained control of the territory in 1821 following its War of Independence, incorporating it into the Mexican Empire. Due to its sparse population, the land became part of larger Mexican states and territories, notably Coahuila y Tejas. To mitigate persistent Comanche raids and boost population, Mexican Texas liberalized its immigration policies, attracting a significant influx of settlers, primarily from the United States.

This period witnessed rapid demographic change; in 1825, Texas counted approximately 3,500 residents, predominantly of Mexican descent, but by 1834, the population surged to about 37,800, with only 7,800 being Mexican-descended. This rapid influx, coupled with open disregard for Mexican laws, particularly the prohibition against slavery, and American attempts to purchase Texas, ignited tensions. Mexican authorities responded in 1830 by prohibiting further immigration from the United States, yet illegal immigration persisted, fueling the growing unrest.

The Anahuac Disturbances in 1832 marked the first open revolt against Mexican rule, reflecting a broader rebellion within Mexico itself. Texians aligned with federalists, successfully driving Mexican soldiers out of East Texas and seizing the opportunity to press for greater political autonomy. This culminated in conventions in 1832 and 1833, where Texians articulated their demands, including independent statehood.

The Texas Revolution erupted in late 1835 with the Battle of Gonzales, leading to the formation of a provisional government that soon dissolved amidst internal strife. Despite early defeats, including the Goliad massacre and the legendary Battle of the Alamo, Texian delegates quickly signed a declaration of independence on March 2, 1836, establishing the Republic of Texas. The pivotal victory at the Battle of San Jacinto, where General Sam Houston’s forces defeated and captured Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna, secured Texas’s independence.

The newly formed Republic of Texas enshrined in its constitution a prohibition against government restriction or freeing of slaves, and mandated the departure of free people of African descent. Fierce political battles ensued between a nationalist faction, led by Mirabeau B. Lamar, advocating for continued independence and expansion to the Pacific, and the faction led by Sam Houston, who favored annexation by the United States and peaceful coexistence with Native Americans.

Despite wide popular support, Texas’s initial application for annexation to the United States in 1836 was rebuffed due to its status as a slaveholding country and Mexican diplomatic pressure. Mexico launched two expeditions into Texas in 1842, briefly capturing San Antonio, but failed to establish an occupying force, ensuring the Republic’s survival. The cotton price crash of the 1840s, however, depressed the young country’s economy.

Texas finally achieved statehood on December 29, 1845, when it was admitted to the U.S. following the election of expansionist James K. Polk. This annexation immediately strained diplomatic relations with Mexico, leading to the Mexican-American War in 1846, sparked by boundary disputes over the Rio Grande and Nueces River. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 concluded the war, solidifying Texas’s borders at the Rio Grande and leading to the Mexican Cession.

In the post-war era, Texas experienced rapid growth, fueled by migrants pouring into its cotton lands, bringing or purchasing enslaved African Americans, whose numbers drastically increased from 58,000 in 1850 to 182,566 by 1860. This burgeoning enslaved population, comprising 30 percent of the state’s total, played a central role in the state’s decision to re-enter conflict following the election of 1860.

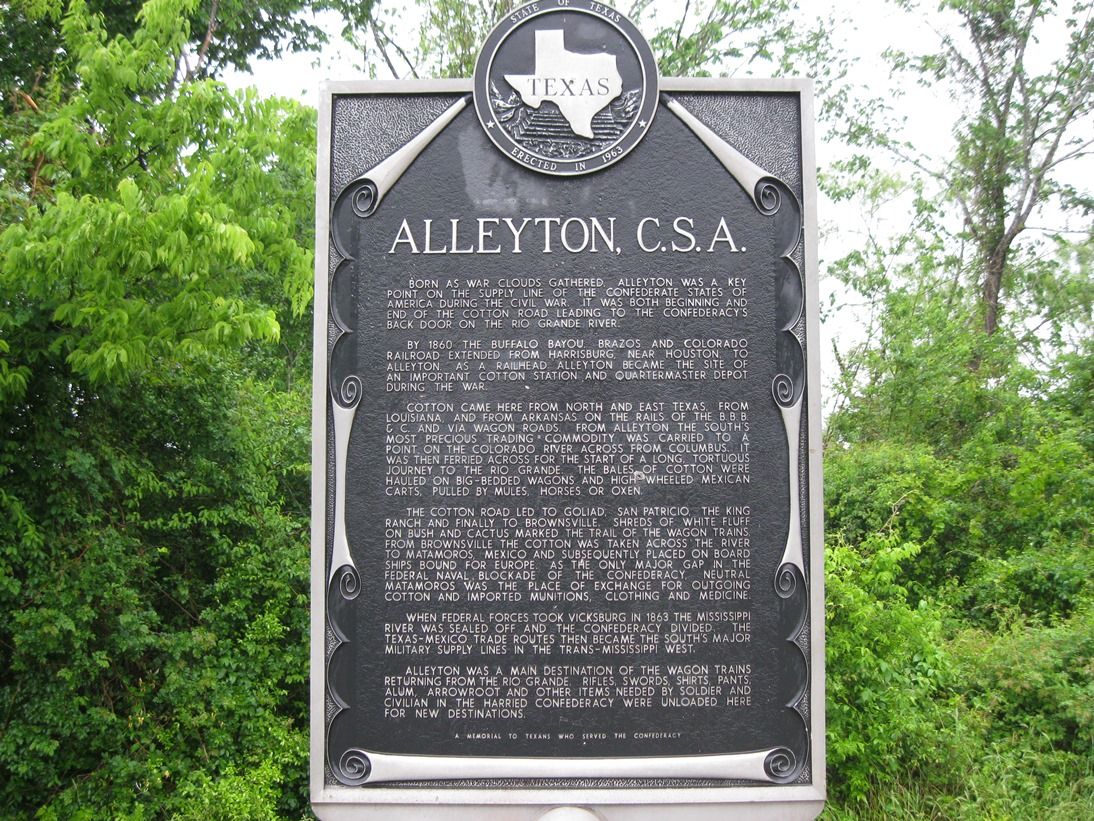

On February 1, 1861, by a vote of 166–8, a state convention in Austin adopted an Ordinance of Secession, which Texas voters approved on February 23. Texas subsequently joined the Confederate States of America on March 4, 1861. Not all Texans favored secession, notably Governor Sam Houston, who was deposed after refusing to swear allegiance to the Confederacy. Though far from the main battlefields, Texas contributed significantly in soldiers and equipment.

Texas served as the “backdoor of the Confederacy,” facilitating trade via its Mexican border, bypassing the Union blockade. Despite Confederate victories in battles like Palmito Ranch, the state’s role as a supply hub diminished after the Union captured the Mississippi River in mid-1863. The period following the Civil War, known as Reconstruction, was marked by anarchy and violence, with Juneteenth commemorating General Gordon Granger’s announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in Galveston nearly two and a half years after its original issuance.

Though devastated by the war, Texas’s economy, less dependent on slavery than other Southern states, recovered more quickly. The late 19th century saw Texas retain many characteristics of a frontier territory, attracting individuals seeking to escape debt or other problems, captured by the common expression “Gone to Texas.” Simultaneously, legitimate businessmen and settlers arrived, contributing to its development.

The cattle industry, though gradually less profitable, continued to thrive, but cotton and lumber emerged as major industries, driving new economic booms. Railroad networks expanded rapidly, and the port at Galveston grew as commerce flourished. By the turn of the 20th century, lumber had become Texas’s largest industry, laying a foundation for future industrialization.

In 1900, Texas endured the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history with the Galveston hurricane. A year later, on January 10, 1901, the discovery of Spindletop, the first major oil well south of Beaumont, initiated a transformative “oil boom.” This monumental find, followed by discoveries in East and West Texas and under the Gulf of Mexico, profoundly reshaped the state’s economy, with oil production peaking at three million barrels per day in 1972.

The early 20th century also saw significant political shifts, as the Democratic-dominated state legislature in 1901 passed a poll tax bill and established white primaries, effectively disenfranchising most Black, poor White, and Latino voters. This dramatically reduced voter participation and cemented Democratic dominance, crushing competition from Republican and Populist parties.

Despite a brief surge in socialist popularity after 1912, their influence waned amidst vilification for their opposition to U.S. involvement in World War I. The Great Depression and the Dust Bowl delivered a double blow to the state’s economy, prompting significant out-migration, particularly of Black people seeking opportunities and escape from segregation in the Northern United States or California.

World War II profoundly impacted Texas, as federal funds poured in for military bases, munitions factories, and hospitals. Hundreds of thousands of Texans served, and cities boomed with new industries, attracting poor farmers from the fields into better-paying war jobs. Texas contributed 3.1 percent of total United States military armaments produced during the war, ranking eleventh among the 48 states.

The mid-20th century marked a pivotal transformation from a predominantly rural and agricultural state to an urban and industrialized powerhouse. Texas, as part of the Sun Belt, experienced robust economic growth, particularly in the 1970s and early 1980s, leading to a diversified economy less reliant on petroleum. By 1990, Hispanics and Latino Americans became the largest minority group, a demographic trend that continues to shape the state.

Texas now boasts the second-highest number of Fortune 500 companies headquartered in the United States, with 52 such entities. It leads in numerous industries, including tourism, agriculture, petrochemicals, energy, computers and electronics, aerospace, and biomedical sciences. Since 2002, Texas has consistently led the U.S. in state export revenue and holds the second-highest gross state product, underscoring its economic might.

The urban centers of the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex and Greater Houston areas rank as the nation’s fourth and fifth most populous urban regions, respectively, serving as vital economic and cultural hubs. The state’s appeal as a destination for migration has been substantial, with Texas named the most popular state to move to for three consecutive years, and a 2019 study indicating a growth rate of 1,000 people per day.

Politically, the late 20th century witnessed a significant shift, as the Republican Party supplanted the Democratic Party as the dominant force in Texas. However, the early 21st century has seen a counter-trend, with metropolitan areas like Dallas–Fort Worth and Greater Austin emerging as centers for the Texas Democratic Party in statewide and national elections, reflecting a growing acceptance of liberal policies within urban areas. This dynamic interplay between deeply rooted conservative traditions and emerging progressive urban centers continues to define Texas’s political identity.

As the state grapples with contemporary challenges, from the COVID-19 pandemic, where it was selected to test Pfizer’s vaccine distribution, to major weather emergencies like Winter Storm Uri in 2021, which exposed vulnerabilities in its power grid, Texas remains a crucible of evolving policy and public discourse. Its sheer scale, complex history, robust economy, and rapidly changing demographics create a unique and often intense environment for political action and public life. The Lone Star State, with its inherent contradictions and remarkable dynamism, stands as a testament to the enduring forces that shape American identity and governance.