Alright, gearheads, history buffs, and anyone who’s ever looked at a grainy photo from the 1970s and thought, “What *was* going on?” Welcome to the ultimate deep dive into a decade that often gets a bad rap, but was, in fact, a seismic shift in global history. We’re talking about the 1970s – a ten-year stretch that kicked off on January 1, 1970, and slammed on the brakes on December 31, 1979. Historians today are increasingly calling it a “pivot of change,” and boy, do they have a point. It was a time when the world’s established order felt like it was riding a bumpy, unpaved road, with foundational elements seemingly disappearing from the rearview mirror at an alarming rate.

Now, you might be wondering, “Trucks? What do trucks have to do with this?” And that’s fair. We’re not talking about literal F-150s or Peterbilts vanishing into thin air (though, let’s be honest, wouldn’t that be a wild article?). No, here at Jalopnik, we see the ’70s through a different lens. We’re looking at the *institutional* and *geopolitical* heavy haulers, the societal mainstays, the very *infrastructure* of global power and North American life that, by the end of the decade, had either broken down, been scrapped, or simply rolled off into a forgotten junkyard. These were the twelve monumental ‘trucks’ – the policies, regimes, and social norms – that once defined the landscape, but by 1979, were conspicuously absent from the North American and global roads we traversed.

So, buckle up. We’re about to navigate the twisted, fuel-crisis-addled highways of the ’70s, piecing together the puzzle of these lost giants. From the shifting sands of war to the crumbling foundations of political power, the decade served up a masterclass in how quickly the seemingly unmovable can become nothing but a faint memory. Let’s start with the first half-dozen of these colossal ‘trucks’ that simply vanished, leaving behind a profoundly altered world for us to inherit.

1. **The US Military Footprint in Vietnam: A Retreat from Southeast Asia**Imagine a political and military commitment that spanned decades, defining an entire generation and tearing at the fabric of a nation. That was the American involvement in the Vietnam War, a conflict that became a festering wound for the United States. As the 1970s dawned, America was still deeply embroiled, but the writing was on the wall. Intense political pressure mounted back home, fueled by leaks like those from *The New York Times* regarding the nation’s involvement. It wasn’t just a distant conflict anymore; it was a daily struggle playing out in living rooms across North America.

The turning point, or perhaps more accurately, the exit ramp, came in 1973 with America’s official withdrawal from the war. This wasn’t a triumphant parade; it was a complex, often painful, extrication. But the saga wasn’t over. The final, undeniable end of this massive ‘truck’ – the long-term US military presence and its proxy in Southeast Asia – arrived with the dramatic Fall of Saigon in 1975. This pivotal event on April 30, 1975, saw the unconditional surrender of South Vietnam, and by the following year, Vietnam was officially reunified under communist rule.

The vanishing act of the US military from Vietnam wasn’t just a geographic shift; it was a psychological one for North America. It marked the end of an era of perceived invincibility, a moment of profound introspection and division. The costly conflict, both in human lives and national treasure, had run its course, leaving behind a complex legacy that continues to be debated. This ‘truck’ had simply driven off the map, leaving a void where a massive military apparatus once stood, forcing America to re-evaluate its role on the global stage. It was a brutal lesson in the limits of power, and one that fundamentally reshaped the nation’s foreign policy outlook for decades to come.

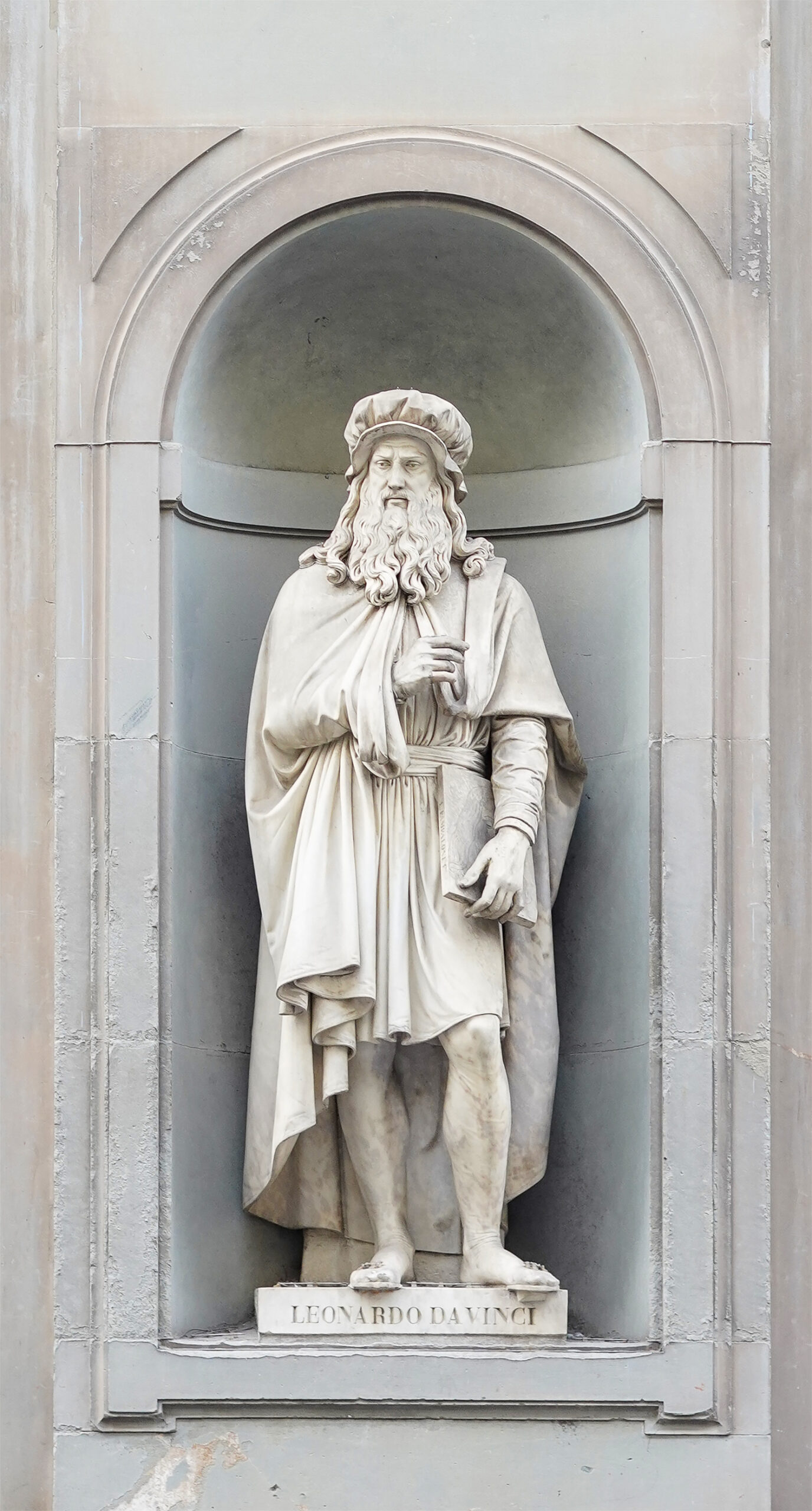

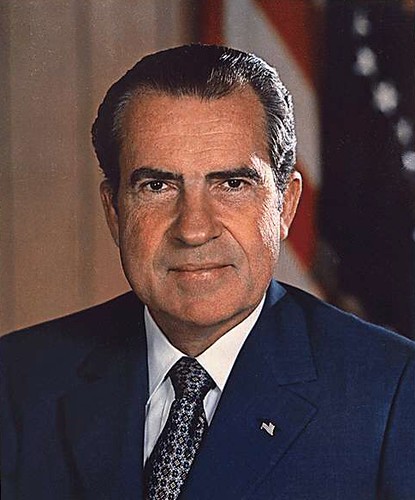

2. **Presidential Stability in the US: The Nixonian Implosion**If the Vietnam War was a slow-motion unraveling, the disappearance of a seemingly invincible American presidency was a sudden, earth-shattering implosion. In the United States, the early 1970s were dominated by President Richard Nixon, a political titan who had achieved significant diplomatic breakthroughs, including restoring relations with China. Yet, beneath the surface, a scandal was brewing that would eventually prove too powerful for even his formidable political machine to withstand: Watergate. This wasn’t just about a break-in; it was about a profound breach of public trust, an executive branch seemingly operating above the law.

The pressure mounted relentlessly, day after day, week after week. Charges for impeachment loomed large, casting a dark shadow over the White House. The institutional ‘truck’ of unchallenged presidential authority, a perceived stability that had largely defined American politics, began to wobble precariously. The media, the public, and finally, Congress, all turned their gaze toward the Oval Office, demanding accountability. This was not merely a political scuffle; it was a constitutional crisis, shaking the very foundations of American governance.

And then, on August 9, 1974, it happened: President Richard Nixon resigned from office. This was an unprecedented event in US history, a sitting president stepping down under duress. The symbolic ‘truck’ of uninterrupted presidential authority and a certain level of governmental decorum disappeared overnight, replaced by a deep sense of cynicism and a profound challenge to established power. It left a lasting mark on the American psyche, reshaping how citizens viewed their leaders and setting a precedent for increased scrutiny and accountability. The Nixonian implosion was a stark reminder that even the most powerful political vehicles can be driven off the road.

3. **The Reign of Keynesian Economics: A Paradigm Shift**For decades, particularly in the post-World War II boom, the economic ‘truck’ driving much of the industrialized world, including North America, was largely designed by John Maynard Keynes. This theory advocated for government intervention to stabilize economies, boost employment, and manage demand. It was the prevailing wisdom, a seemingly robust engine powering prosperity. Then came the 1970s, and with it, a series of shocks that exposed cracks in the Keynesian chassis, proving that even the most established economic models can suddenly run out of gas.

The most significant of these shocks was the 1973 oil crisis. Caused by oil embargoes imposed by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), this event sent ripple effects through developed economies, leading to widespread financial crisis. Fuel prices soared, industries struggled, and consumers faced unprecedented uncertainty. This wasn’t just a hiccup; it was a full-blown economic emergency that highlighted the interdependence of global economies and the fragility of energy supplies, especially for import-reliant nations in North America and Europe.

What made this crisis particularly perplexing was the emergence of “stagflation” – a toxic combination of economic stagnation, high unemployment, and inflation. Keynesian models struggled to explain, let alone resolve, this new phenomenon. Consequently, the crisis initiated a profound political and economic trend: the replacement of Keynesian economic theory with neoliberal economic theory. This signaled a fundamental shift in how governments approached economic management, advocating for reduced government spending, deregulation, and free markets. The old Keynesian ‘truck’ had definitively broken down on the side of the road, giving way to a new, leaner vehicle that would drive economic policy for decades to come, first coming to power with the 1973 Chilean coup d’état.

4. **The Shah’s Pro-Western Iran: A Geopolitical Powerhouse’s Fall**In the complex chess game of Cold War geopolitics, Iran under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was a significant, pro-Western piece. For years, this alliance provided stability and a crucial bulwark against Soviet influence in the Middle East, with the Shah’s regime enjoying strong support from the United States and other Western powers. Iran was, in essence, a well-oiled geopolitical ‘truck’ reliably navigating the treacherous terrain of international relations, ensuring Western access to vital oil resources and providing strategic intelligence. Its internal political structure, while autocratic, was seen as a necessary partner in the larger global struggle.

However, beneath the veneer of stability, deep currents of discontent were swirling. The Shah’s modernization efforts, coupled with perceived corruption, political repression, and his close ties to the West, fueled growing opposition from various segments of Iranian society, including religious leaders and a burgeoning revolutionary movement. This internal pressure began to chip away at the regime’s foundation, creating instability that the Pahlavi dynasty, despite its powerful external backing, ultimately couldn’t withstand.

The year 1979 saw these simmering tensions explode into the Iranian Revolution, a transformative event that completely dismantled this geopolitical ‘truck.’ The revolution ousted Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, replacing his autocratic pro-Western monarchy with a theocratic Islamic government under the leadership of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. This wasn’t just a change in leadership; it was a fundamental reorientation of Iran’s identity and international alignment. The “distrust between the revolutionaries and Western powers” immediately manifested, most dramatically in the Iran hostage crisis on November 4, 1979, where 66 diplomats, mainly from the United States, were held captive. The disappearance of the Shah’s Iran from the Western orbit left a gaping hole in regional power dynamics and profoundly reshaped the relationship between the Islamic world and the West.

5. **European Colonial Dominance: The Last Gasps of Empire**For centuries, a powerful ‘truck’ of European colonial dominance had reshaped continents, drawing borders and dictating destinies, particularly in Africa. While the post-World War II era had seen a wave of decolonization, the 1970s marked the final, dramatic acts in this long-running historical drama. It was a time when the last vestiges of these sprawling empires finally gave way, fundamentally altering the global political map and signaling the end of an era that had defined international relations for centuries.

A major catalyst for this final push was the Carnation Revolution in Portugal in 1974. This military coup, organized by officers who opposed the Portuguese fascist regime, quickly garnered popular civil support. Its success directly led to the decolonization of all Portugal’s colonies. Suddenly, in 1975, Angola and Mozambique gained their independence, after years of struggle. This wasn’t just a regional event; it was a global reverberation, demonstrating that the old imperial models were finally unsustainable, even for some of Europe’s longest-standing colonial powers.

Adding to this definitive end, Spain officially withdrew its claim over Spanish Sahara in 1976, formally bringing the Spanish Empire to a close. These events represent the dramatic “disappearance” of a historical ‘truck’ that had transported resources, cultures, and governance across vast oceans. Its breakdown in the 1970s created new, independent nations but also, as the context notes, left “power vacuums that led to civil war in newly independent Lusophone African nations,” highlighting the complex and often turbulent aftermath of empire. The reverberations of these shifts were felt worldwide, including in North America, as global power dynamics continued to evolve.

6. **Authoritarian Rule in Spain: Franco’s End and Democracy’s Dawn**In the heart of Western Europe, a very different kind of ‘truck’ had been stubbornly rumbling along since the Spanish Civil War: the authoritarian dictatorship of Francisco Franco. For nearly four decades, Franco’s iron grip had maintained a rigid, conservative order, effectively isolating Spain from many of the liberalizing trends sweeping the rest of Europe. This regime represented a static, almost anachronistic political structure, a powerful, slow-moving vehicle resistant to change, contrasting sharply with the progressive values gaining traction in other industrialized countries during the 1960s and early 1970s.

However, even the most entrenched systems have a lifespan. On November 20, 1975, after 39 years in power, Francisco Franco died. His death was not merely the passing of an individual; it was the final, decisive shutdown of the entire dictatorial ‘truck.’ Almost immediately, a remarkable transformation began. Juan Carlos I, crowned king of Spain, called for the reintroduction of democracy, a bold move that set the country on a dramatically new course. The first general elections since the Second Republic were held in 1977, ushering in Adolfo Suárez as Prime Minister.

The disappearance of Franco’s dictatorship paved the way for a rapid and largely peaceful transition to democracy. Socialist and Communist parties, once banned, were legalized. The current Spanish Constitution was signed in 1978, codifying the nation’s new democratic principles. This dramatic shift was a testament to the resilience of democratic aspirations and the willingness of a nation to shed its authoritarian past. This European ‘truck’ of dictatorship had finally been decommissioned, opening up Spain’s roads to a vibrant, pluralistic future, and serving as a powerful example of political evolution in a decade of upheaval. The end of this long-standing authoritarian regime marked a significant moment for the continent, aligning Spain with the democratic values increasingly cherished by North American and Western European nations.

Alright, folks, if you thought the first half of the ’70s was a wild ride, buckle up, because the back end of the decade didn’t exactly hit cruise control. The geopolitical landscape continued to shift at warp speed, and some truly colossal ‘trucks’ that once seemed permanent fixtures on the global highway simply evaporated. We’re diving deeper into this fascinating, often turbulent, era to uncover the next six monumental disappearances that left an indelible mark on North America and the world. From the sudden chill in superpower relations to the tragic implosion of grand social experiments and the downfall of entrenched regimes, the 1970s kept right on delivering seismic shifts right up to the finish line.

7. **The Policy of Détente: A Sudden U-Turn**For much of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the world’s two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, seemed to be applying the brakes to their bellicose confrontations. This era, known as détente, was essentially a policy promoting the idea that the world’s problems could be resolved at the negotiating table, a welcome shift from the hair-trigger tensions of earlier decades. It was seen as a way to avoid driving the world dangerously close to nuclear war, and let’s be honest, who wasn’t ready for a little less Cold War anxiety?

Part of this shift came from the US finding itself in a weakened position after the grueling failure of the Vietnam War. So, as a counterweight against Soviet expansionism, the US even restored ties with the People’s Republic of China. Both nations, in a rare moment of agreement, endorsed nuclear nonproliferation, trying to keep the deadliest weapons out of the wrong hands. This was the big, gleaming ‘truck’ of peaceful coexistence, designed to make the international road a bit smoother.

Yet, beneath this veneer of cooperation, the geopolitical rivalry between the US and the Soviet Union was still rumbling along. It just shifted gears, becoming more indirect but no less intense. Both American and Soviet intelligence agencies were relentlessly jockeying for control of smaller countries, pouring funding, training, and material support into insurgent groups, governments, and armies across the globe. It was a high-stakes game of international tug-of-war, even if the direct confrontations were less frequent.

But every road has an end, and for détente, it was a sudden, dramatic dead-end. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan at the close of 1979 abruptly ended this policy of lessened tensions. This wasn’t just a political misstep; it was a full-on collision, signaling a return to a more confrontational era of the Cold War. The ‘truck’ of détente, once a symbol of hope for a calmer world, was summarily pulled off the road, leaving behind a profound chill in superpower relations.

8. **The Cambodian Experiment: From Lon Nol to the Khmer Rouge’s Abyss**Before 1975, Cambodia was navigating a rough patch, with its American-backed government under Lon Nol grappling with internal conflicts. But when the ’70s rolled around, nobody could have predicted the sheer scale of the societal overhaul that was about to hit. It was a country teetering on the edge, and in 1975, it plummeted into an abyss orchestrated by a regime with a chilling vision.

On April 17, 1975, the communist forces of Pol Pot, known as the Khmer Rouge, swept into the capital, Phnom Penh. This wasn’t just a change of government; it was the start of a radical, terrifying social experiment. The Khmer Rouge immediately began emptying the cities, forcing millions into the countryside to clear jungles and establish a Marxist agrarian society. Imagine entire populations, regardless of their background, suddenly repurposed as forced laborers. It was a forced migration on an unimaginable scale, effectively dismantling Cambodia’s existing social fabric overnight.

The brutality that followed was horrific. The Khmer Rouge systematically targeted anyone perceived as a threat to their new order: Buddhist priests and monks, anyone who spoke foreign languages, those with an education, or even people who wore glasses. They were all considered enemies of the state, subjected to torture or summary execution. The death toll was staggering, with as many as 3 million people perishing under this regime. This ‘truck’ of radical ideology was driven with absolute, unfeeling ruthlessness.

Thankfully, this tragic social experiment didn’t last the entire decade. In early 1979, Vietnam invaded Cambodia, decisively overthrowing the Khmer Rouge and installing a satellite government. While this brought an end to the genocide, it immediately sparked a brief but furious border war with China in February of that same year. The ‘truck’ of Pol Pot’s Democratic Kampuchea, a dark detour in human history, finally crashed and burned, but not without leaving an immense scar on the world.

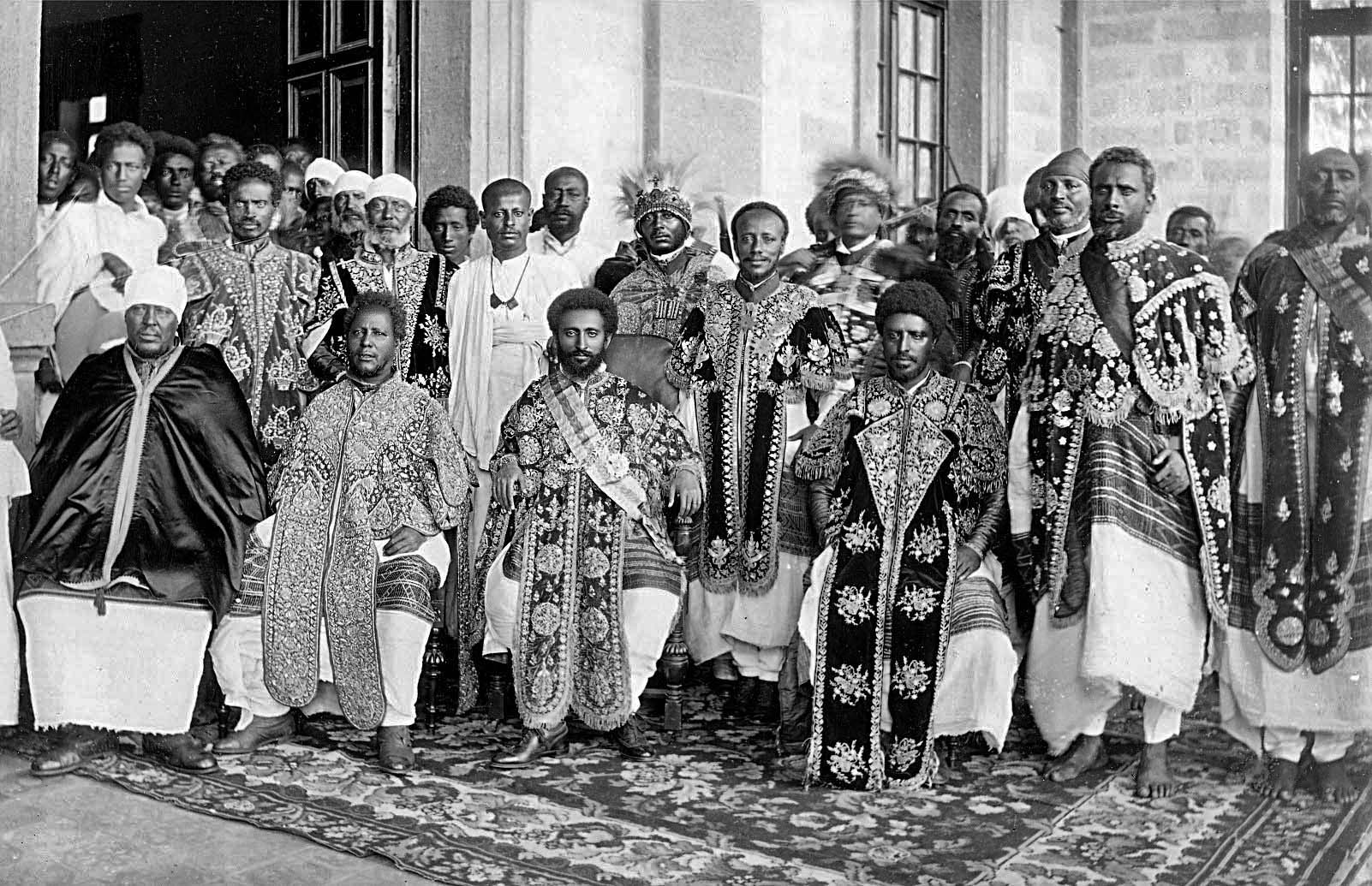

9. **Haile Selassie’s Ancient Monarchy: The End of an Era in Ethiopia**For centuries, Ethiopia had been defined by a deep and unwavering connection to its imperial past, embodied by Emperor Haile Selassie. His rule represented one of the longest-lasting monarchies in world history, a ‘truck’ that had traversed millennia, carrying the weight of tradition and a unique African heritage. In an era when most of Africa was grappling with the aftermath of colonial rule, Ethiopia stood as a proud, ancient empire.

But even the most venerable institutions are not immune to the winds of change, especially during the tumultuous 1970s. The continent was rife with military coups and political instability in the wake of decolonization, and Ethiopia was no exception. By 1974, internal discontent and external pressures reached a boiling point, leading to a military coup. It was a swift, decisive move orchestrated by a communist junta.

This wasn’t just another change of leadership; it was the absolute, definitive end of an imperial lineage stretching back to biblical times. Haile Selassie was overthrown, and with his removal, the ancient ‘truck’ of Ethiopian monarchy was permanently decommissioned. His replacement by the communist junta, led by figures like General Aman Andom and Mengistu Haile Mariam, dramatically altered the nation’s trajectory. It was a profound vanishing act, replacing a thousands-year-old tradition with a modern, ideological regime, completely reshaping Ethiopia’s identity on the global stage.

Read more about: 12 ’70s Power Players & Pivots: The Dominant Forces That Shaped a Decade, Then Disappeared or Transformed!

10. **Idi Amin’s Uganda: The Brutal Reign and Collapse of a ‘Strongman’**In 1971, a new, menacing ‘truck’ rumbled onto the scene in Uganda: the military dictatorship of Idi Amin. Rising to power through a coup, Amin quickly established himself as a brutal and unpredictable leader, making his mark as one of the most infamous dictators of the 20th century. For nearly a decade, his regime persecuted opposition with ruthless efficiency, snuffing out any dissent and consolidating his iron grip on the nation.

Amin’s rule wasn’t just about political repression; it was also marred by a deeply disturbing racist agenda. He initiated a mass expulsion of Asians from Uganda, particularly those of Indian descent who had been an integral part of Ugandan society since British colonial rule. This xenophobic policy devastated the nation’s economy and society, creating widespread suffering and further isolating Uganda from the international community.

The wheels of Amin’s brutal ‘truck’ began to come off in 1978. Driven by an expansionist agenda, he initiated the Ugandan–Tanzanian War, making a bold but ultimately disastrous move to annex territory from neighboring Tanzania. This was a massive overreach, and it proved to be the beginning of the end for his dictatorial rule. The forces of Tanzania, with the support of Ugandan exiles, pushed back.

By 1979, Amin’s regime, once seemingly invincible, completely collapsed under the weight of its own aggression and the determined opposition. The Ugandan defeat in the war led directly to Amin’s overthrow and eventual exile. The ‘truck’ of his brutal dictatorship, which had inflicted so much pain and instability, finally careened off the road, leaving behind a shattered nation grappling with a legacy of violence and economic ruin.

11. **The Somoza Dynasty in Nicaragua: A Dynastic Downfall**For over four decades, Nicaragua had been steered by a single, powerful ‘truck’: the Somoza dynasty. This entrenched dictatorship, often with strong backing from the United States, represented a long-standing, seemingly unmovable pillar of Central American politics. It was a dynastic rule that weathered many storms, maintaining its grip through a combination of political maneuvering, military control, and international alliances.

However, the 1970s proved to be a decade where even the most deeply rooted ‘trucks’ could be uprooted. Beneath the surface of authoritarian control, a revolutionary fervor was building, challenging the very foundations of the Somoza regime. The Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) emerged as a formidable opposition, attracting widespread support from various segments of Nicaraguan society tired of the entrenched power and perceived corruption.

By 1979, the simmering discontent boiled over into a full-scale uprising. The Sandinistas, through sustained guerrilla warfare and popular mobilization, achieved the unthinkable: they ousted the Somoza dictatorship. This was a monumental political overthrow, a definitive ‘disappearance’ of a dynastic rule that had shaped Nicaragua for generations. The old ‘truck’ was gone, replaced by the hopes and uncertainties of a new, revolutionary government.

Yet, as with many such dramatic shifts, the road ahead remained fraught with peril. The overthrow of the Somoza dynasty by the Sandinistas in 1979, while celebrated by many, immediately sowed the seeds of future conflict. This pivotal event directly led to the infamous Contra War in the 1980s, proving that while one ‘truck’ may vanish, its absence often creates new, turbulent landscapes for others to navigate.

12. **Yugoslavia’s Centralized Unity: The Cracks in Tito’s Grand Design**Yugoslavia, under the firm but nuanced hand of communist ruler Joseph Broz Tito, was a fascinating and complex ‘truck’ on the European road. It was an ambitious social experiment, attempting to forge a unified, multi-ethnic state in a region historically prone to division. For decades, Tito’s centralized control kept the disparate republics of Yugoslavia together, a powerful engine driving a unique brand of non-aligned communism.

However, even this carefully constructed unity began to show significant cracks in the 1970s. The ‘truck’ started to rattle with growing internal tensions, most notably with the Croatian Spring movement in 1971. This wasn’t just a minor protest; it was a powerful demand for greater decentralization of power to the constituent republics. It was a clear signal that the centralized model, while effective for a time, was facing serious challenges.

Tito, a master politician, initially subdued the Croatian Spring movement, arresting its leaders. But he also understood the need for change. This led to a major constitutional reform in 1974, which fundamentally altered the ‘truck’s’ internal mechanics. The new constitution decentralized powers to the republics, even granting them the official right to separate from Yugoslavia. It also significantly weakened Serbia’s influence by empowering its autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. While it consolidated Tito’s personal power by proclaiming him president-for-life, this ‘truck’ of central control began to dismantle itself from within.

This 1974 Constitution, while a response to calls for autonomy, ultimately became deeply resented by Serbs and began a gradual escalation of ethnic tensions. It marked the slow but inexorable ‘disappearance’ of Yugoslavia’s former centralized unity, laying the groundwork for the tragic conflicts that would erupt decades later. The ‘truck’ of Tito’s grand design, intended to foster unity, instead developed systemic faults in the ’70s that would eventually lead to its catastrophic breakdown, demonstrating that even a strong vision can unravel under the weight of internal pressures.

And there you have it, folks – the remaining pieces of the ’70s puzzle, a decade where the world changed in ways few could have predicted. From global superpowers shifting gears in Afghanistan to radical social experiments imploding in Cambodia, and the long-standing political heavy haulers of Ethiopia, Uganda, and Nicaragua being driven off the map, the 1970s truly lived up to its billing as a “pivot of change.” These twelve ‘trucks,’ these monumental shifts, didn’t just disappear; they fundamentally reshaped the roads we travel today. It was a decade of monumental breakdowns and unexpected detours, leaving us with a world that was, in many ways, unrecognizable from the one that started it. What an era, right?