.jpg)

The 1970s, often perceived through a haze of disco lights and economic uncertainty, was in fact a decade of unprecedented global transformation, acting as a crucial “pivot of change” in world history. Far from a mere transition period, the ’70s engineered a fundamental reshaping of international relations, economic paradigms, and societal structures. It was an era where the aftershocks of postwar economic booms gave way to new challenges, setting the stage for the modern world we recognize today.

This decade, spanning from January 1, 1970, to December 31, 1979, was characterized by an incredible dynamism across all sectors. From the shifting sands of global power to the intricate dance of technological innovation, and from deeply felt social progress to devastating natural and non-natural calamities, the ’70s delivered a relentless series of high-impact events. It was a period that demanded adaptation and redefined the very concept of global interdependence, showcasing how deeply intertwined economies and political fates had become.

As we embark on this journey through the ’70s, we aim to dissect the raw power and intricate mechanics behind 14 of the decade’s most significant events. Much like evaluating a high-performance engine, we will examine the components, the forces, and the enduring legacy of these pivotal moments. This deep dive will offer a robust understanding of the ’70s, moving beyond nostalgic headlines to reveal the true historical ‘muscle’ that propelled us into the new century.

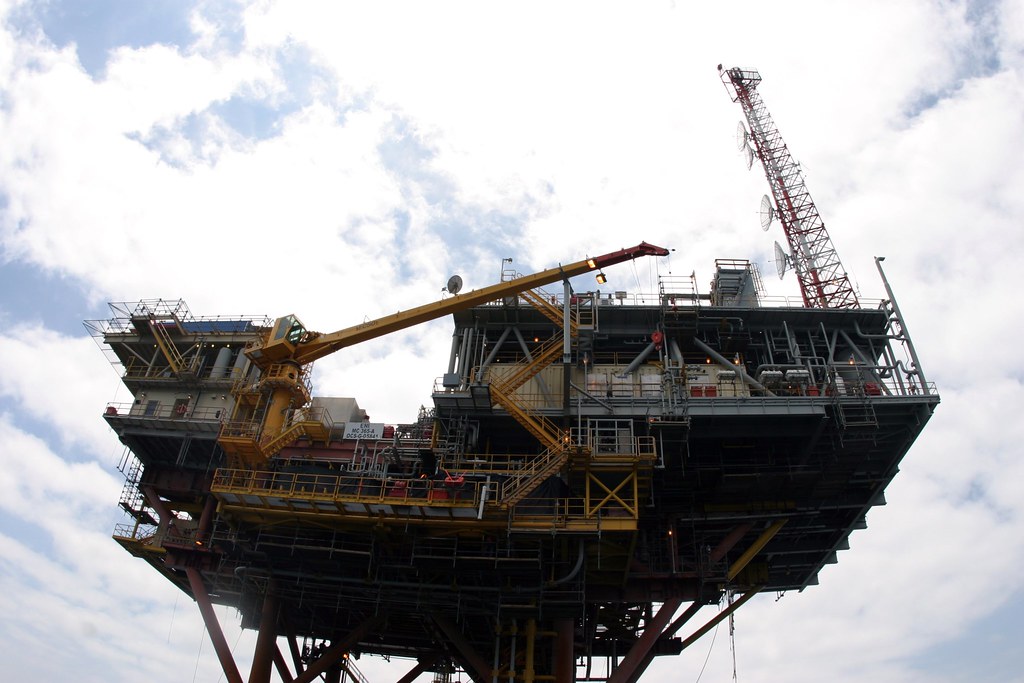

1. **The Economic Earthquake: Oil Crises and the Rise of Stagflation (1973, 1979)**

The 1970s witnessed a monumental shift in the global economic landscape, largely triggered by the seismic events of the 1973 and 1979 oil crises. These were not mere price fluctuations; they were a fundamental re-engineering of the world’s energy and financial systems. The Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) initiated oil embargoes that sent shockwaves through industrialized nations, sparking a financial crisis that reverberated globally. This sudden constriction of supply underscored the fragility of economies heavily reliant on imported oil and exposed deep-seated vulnerabilities.

The aftermath of the oil crisis introduced a new and perplexing economic phenomenon: stagflation. This counterintuitive blend of high inflation, slow economic growth, and rising unemployment defied conventional Keynesian economic theory, which had dominated policy-making for decades. Governments found themselves in an unprecedented bind, as traditional tools for combating inflation often exacerbated unemployment, and vice-versa. The crisis revealed a severe limitation in existing economic models and necessitated a radical re-evaluation of policy.

The intellectual and practical response to stagflation heralded a profound political and economic trend: the gradual replacement of Keynesian economic theory with neoliberal economic theory. This paradigm shift advocated for reduced government spending, deregulation, and free-market principles. The first tangible manifestation of this transition in governance came with the 1973 Chilean coup d’état, which brought to power a neoliberal government. This event signaled a new era where market forces would increasingly dictate national and international economic strategies, fundamentally altering the trajectory of global capitalism.

The 1979 energy crisis further cemented these shifts, reinforcing the lesson that resource control could exert immense geopolitical leverage. The economic shocks of the ’70s were more than just a blip; they were the catalysts for a complete recalibration of economic thought and practice, the effects of which would extend far beyond the decade. They highlighted the interdependence of economies since World War II and exposed the vulnerabilities inherent in a globalized system, paving the way for new economic orthodoxies.

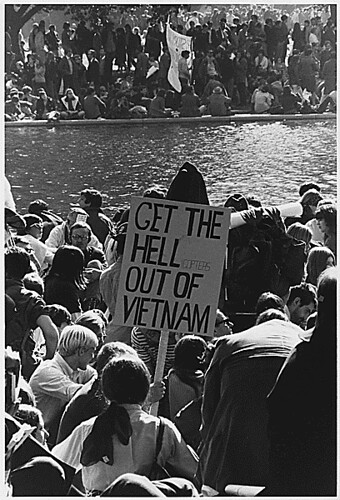

2. **The Long Goodbye: America’s Withdrawal from Vietnam (1973-1975)**

The protracted conflict in Vietnam, a defining feature of the previous decade, finally reached its agonizing conclusion in the 1970s, leaving an indelible mark on American and global consciousness. The United States had been embroiled in the Vietnam War since the mid-1950s, but the early 1970s saw escalating political pressure to disengage. Public opinion, fueled by leaked information from The New York Times regarding the nation’s involvement, became a powerful engine driving the demand for withdrawal. This internal pressure eventually compelled America’s government to act decisively.

In 1973, the United States officially withdrew its military forces from the Vietnam War, marking a symbolic end to direct American combat involvement. However, the conflict itself continued. The ultimate resolution came two years later, with the dramatic Fall of Saigon in April 1975. This pivotal event, characterized by frantic evacuations of South Vietnamese, signaled the unconditional surrender of South Vietnam and the effective end of the war. It was a moment laden with geopolitical significance, demonstrating the limits of superpower military might.

The following year, Vietnam was officially declared reunited, closing a chapter of intense division and conflict that had spanned decades. The resolution of the Vietnam War profoundly impacted international relations, particularly for the United States, leading to a period of introspection regarding its foreign policy and military interventions. It also played a role in the broader cooling of superpower tensions, contributing to the policy of détente, as the US found itself in a weakened position post-Vietnam.

The legacy of the Vietnam War’s conclusion in the ’70s extended beyond geopolitics, influencing cultural and social narratives for generations. It brought into sharp focus the human cost of conflict and the complexities of international engagement. For many, it represented a watershed moment in the exercise of global power, demonstrating that military strength alone could not always dictate political outcomes. The withdrawal and subsequent reunification of Vietnam were powerful indicators of a changing global order.

3. **Decolonization’s Aftermath: New Nations and Persistent Conflict in Africa**

The 1970s represented a crucial, albeit often tumultuous, phase in Africa’s ongoing journey of decolonization, as new nations emerged from the shadows of European empires. A significant turning point came in 1975 when Angola and Mozambique gained their independence from the Portuguese Empire. This was a direct consequence of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, which overthrew the fascist regime and initiated a rapid dismantling of its colonial holdings. These newfound freedoms, however, frequently led to power vacuums and internal strife.

Further reshaping the continent’s map, Spain formally withdrew its claim over Spanish Sahara in 1976, marking the official end of the Spanish Empire. While celebrated as milestones in self-determination, the paths of these newly independent states were seldom smooth. The context makes clear that Africa during this decade was “plagued by endemic military coups, with the long-reigning Emperor of Ethiopia Haile Selassie being removed, civil wars and famine.” This period was less about tranquil nation-building and more about a continent grappling with the profound complexities of post-colonial governance.

The internal dynamics of these emerging nations were often volatile, as various factions vied for control. The Angolan Civil War, for instance, which began in 1975, drew in international players like Cuba and South Africa, transforming it into a proxy battleground for Cold War ideologies. Similarly, conflicts such as the Ogaden War (1977-1978) between Somalia and Ethiopia, or the Ugandan–Tanzanian War (1978-1979) which overthrew Idi Amin, underscored the fragility of peace and the prevalence of armed conflict throughout the region.

Despite the economic progress some developing economies made through the Green Revolution in the early 1970s, the oil crisis slowed their growth, and political instability became a recurring theme. The decade highlighted that independence was not an endpoint but a complex beginning, often marked by internal struggles, external interference, and profound human suffering. Africa’s experience in the ’70s was a powerful testament to the challenges inherent in forging national identity and stability after centuries of colonial rule.

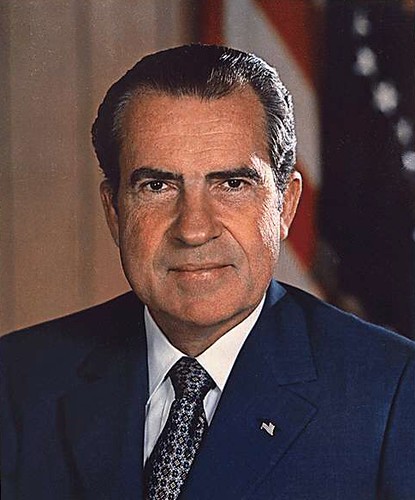

4. **China’s Grand Opening: From Isolation to Global Player (1971-1979)**

The 1970s marked an extraordinary pivot for the People’s Republic of China, transitioning from a state of relative international isolation to re-engagement with the global community, fundamentally altering the Cold War’s geopolitical chessboard. A pivotal moment occurred in 1971 when its representatives replaced those of the Republic of China (Taiwan) at the United Nations, signaling a worldwide recognition of Beijing’s legitimacy. This diplomatic breakthrough paved the way for more direct interactions with Western powers.

The most dramatic step towards rapprochement came with US President Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972, following preparatory visits by Henry Kissinger in 1971. This act, unthinkable just a few years prior, restored relations between the two countries, even though formal diplomatic ties were not established until 1979. This strategic move by the United States was partially intended as a counterweight against Soviet expansionism, demonstrating how the ’70s were characterized by subtle superpower maneuvering.

Internally, 1976 proved to be a watershed year for China with the deaths of both Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. These events effectively brought an end to the Cultural Revolution, ushering in a new era of leadership and policy. After a brief period under Mao’s chosen successor, Hua Guofeng, Deng Xiaoping emerged as China’s paramount leader. Deng quickly began to steer the country away from ideologically driven policies and towards market economics, initiating reforms that would transform China into an economic powerhouse.

The decade concluded with Deng Xiaoping’s visit to the US in 1979, cementing the re-established ties and signaling China’s firm commitment to its new path of economic liberalization and international engagement. This transformation was not merely an internal affair; it profoundly impacted global dynamics, demonstrating the “interdependence of economies since World War II” and adding a complex new player to the already polarized world between the United States and the Soviet Union. China’s ’70s journey was a masterclass in strategic geopolitical and economic repositioning.

5. **Middle East Crucible: Wars, Peace, and Revolution (1973-1979)**

The Middle East in the 1970s was a region of intense volatility, experiencing both devastating conflicts and groundbreaking peace initiatives, ultimately concluding with a revolutionary upheaval that reshaped its political landscape. The decade began with an initial increase in violence as Egypt and Syria declared war on Israel in October 1973, launching the Yom Kippur War. The surprise attack inflicted heavy losses on the Israelis before they managed to rally, repel the Egyptians, and counter a simultaneous Syrian attack in the Golan Heights, even crossing the Suez Canal into Egypt proper.

Despite the bloody conflict, the late 1970s brought an unexpected and fundamental alteration to the situation. In 1978, Egypt, under President Anwar Sadat, signed a peace treaty with Israel at Camp David in the United States. These Camp David Accords led directly to the 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty, effectively ending outstanding disputes between the two nations and earning Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin the 1978 Nobel Peace Prize. This historic agreement showcased a rare instance of diplomatic success in a highly contested region, though Sadat’s actions would tragically lead to his assassination in 1981.

However, as peace cautiously emerged in one part of the Middle East, political tensions in Iran exploded with the Iranian Revolution in 1979. This momentous event overthrew the autocratic pro-Western monarchy of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, transforming Iran into a theocratic Islamist government under the leadership of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The revolution was a seismic shift, introducing a new “wrinkle” in global geopolitics with the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, and a state declared hostile to both Western democracy and “godless communism.”

The Iranian Revolution quickly led to the Iran hostage crisis on November 4, 1979, where 66 diplomats, primarily from the United States, were held captive for an astonishing 444 days. This event not only captured global attention but also significantly impacted international attitudes toward the Muslim faith and demonstrated the burgeoning distrust between revolutionaries and Western powers. The Middle East of the ’70s was a true crucible, forging new political realities through both war and revolutionary change.

6. **The Iron Ladies and Beyond: Women in Global Leadership (1970s)**

The 1970s marked a quiet yet profound revolution in global politics, characterized by the visible presence and rise of a significant number of women as heads of state and heads of government across various countries. This era saw many women becoming the first to hold such influential positions, challenging long-standing patriarchal structures and reflecting the growing social progressive values that had begun in the 1960s, particularly the increasing political awareness and economic liberty of women.

Among these trailblazers was Soong Ching-ling, who continued as the first Chairwoman of the People’s Republic of China until 1972. In Argentina, Isabel Perón made history as the first woman President in 1974, though her tenure was cut short when she was deposed in 1976. The Central African Republic saw Elisabeth Domitien become its first woman Prime Minister. India continued to be led by Indira Gandhi until 1977, demonstrating sustained female leadership in a major global power.

Towards the end of the decade, more pivotal figures emerged. Lidia Gueiler Tejada became the interim President of Bolivia, serving from 1979 to 1980. Portugal saw Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo rise to become its first woman Prime Minister in 1979. Perhaps one of the most enduring symbols of this shift was Margaret Thatcher, who, following the 1979 election in the United Kingdom, became the first female British Prime Minister, initiating a neoliberal economic policy that would redefine the UK’s economic and social landscape.

This collective ascent of women into the highest echelons of power was a clear manifestation of an evolving global ethos in the 1970s. It reflected “increasingly flexible and varied gender roles for women in industrialized societies” and the socioeconomic effect of an ever-increasing number of women entering the non-agrarian economic workforce. While the gender role of men largely remained that of a breadwinner, the ’70s undeniably demonstrated a powerful and irreversible stride towards greater political inclusion and visibility for women on the world stage.

7. **Cold War’s Shifting Tides: Détente, Stagnation, and the Soviet-Afghan War (1970s-1979)**

The Cold War, the defining geopolitical struggle of the post-WWII era, experienced a complex evolution throughout the 1970s, characterized by periods of eased tensions, internal stagnation within the Soviet Union, and a dramatic resurgence of conflict at the decade’s close. Superpower tensions, which had brought the world dangerously close to nuclear war in previous decades, had cooled. This led to the policy of détente, which promoted the idea that global problems could be resolved at the negotiating table, with both the US and Soviet Union endorsing nuclear nonproliferation.

Under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet Union, possessing the largest armed forces and nuclear arsenal, actively pursued this agenda to lessen tensions with its rival superpower, the United States, for much of the seventies. This era, while known as a “period of stagnation” in Soviet historiography, is paradoxically largely considered a “golden age of the USSR in terms of stability and relative well-being.” However, beneath this veneer, hidden inflation continued to increase, and production consistently fell short of demand in critical sectors like agriculture and consumer goods manufacturing. By the end of the ’70s, “signs of social and economic stagnation were becoming very pronounced.”

Despite the efforts at détente, the US–Soviet geopolitical rivalry persisted, albeit in a more indirect faction. Both superpowers relentlessly jockeyed for control of smaller countries, with intelligence agencies providing funding, training, and material support to various groups across the globe, each seeking a geopolitical advantage. This indirect competition fueled numerous coups, civil wars, and terrorist activities across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Europe, where Soviet-backed Marxist terrorist groups were active. Over half the world’s population in the 1970s lived under a repressive dictatorship, highlighting the global reach of this ideological struggle.

The fragile policy of détente abruptly and decisively ended with a monumental event at the close of the decade: the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan on December 27, 1979. Although the Soviet–Afghan War would predominantly unfold throughout the 1980s, its genesis in the ’70s represented a dramatic escalation of Cold War hostilities. This invasion not only ended the illusion of sustained peace but also solidified the global polarization between the United States and the Soviet Union, setting the stage for a renewed period of intense geopolitical confrontation.

The 1970s was a decade that ceaselessly challenged the established order, presenting a cascade of events that forever altered the global landscape. While Section 1 explored the initial economic, geopolitical, and social reconfigurations, our journey through this transformative era continues with an examination of the decade’s more internal conflicts, the chilling rise of global terrorism, astounding technological breakthroughs, and the devastating impact of both natural and human-made disasters that truly tested humanity’s resilience. These remaining seven pivotal moments collectively paint a comprehensive picture of the ’70s’ intricate tapestry of events, revealing the hidden forces that shaped our modern world.

8. **The Cambodian Genocide: A Shadow of Ideology and Annihilation (1975-1979)**

As the Vietnam War drew to a close, a new and horrifying chapter unfolded in neighboring Cambodia, illustrating the brutal consequences of radical ideological fervor. In April 1975, the communist Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, successfully overthrew the American-backed government of Lon Nol, capturing the capital, Phnom Penh. This victory ushered in a dark period of national restructuring aimed at creating a radical, Marxist agrarian society, a vision that demanded an unimaginable human cost.

The regime’s policies were characterized by extreme authoritarianism and a profound disregard for human life. Pol Pot’s forces immediately initiated forced evacuations of cities, compelling the urban population to clear jungles and engage in grueling agricultural labor. The Khmer Rouge systematically targeted and persecuted anyone deemed an intellectual, a threat, or an undesirable element: Buddhist priests and monks, individuals who spoke foreign languages, those with any form of education, or even people wearing glasses, were subjected to torture and execution.

This horrifying campaign of state-sponsored violence and starvation, known as the Cambodian genocide, is estimated to have resulted in the deaths of as many as 3 million people. The scale of the atrocity was staggering, showcasing a deliberate attempt to erase perceived societal impurities and establish an unadulterated communist utopia through mass murder and cultural destruction. It stands as one of the most tragic internal conflicts of the 20th century.

The Cambodian genocide continued until the start of 1979 when Vietnam invaded the country, subsequently overthrowing the Khmer Rouge and installing a satellite government. This intervention, however, was not without its own international repercussions, provoking a brief but furious border war with China in February of that year, further demonstrating the complex web of regional and global interactions during the 1970s.

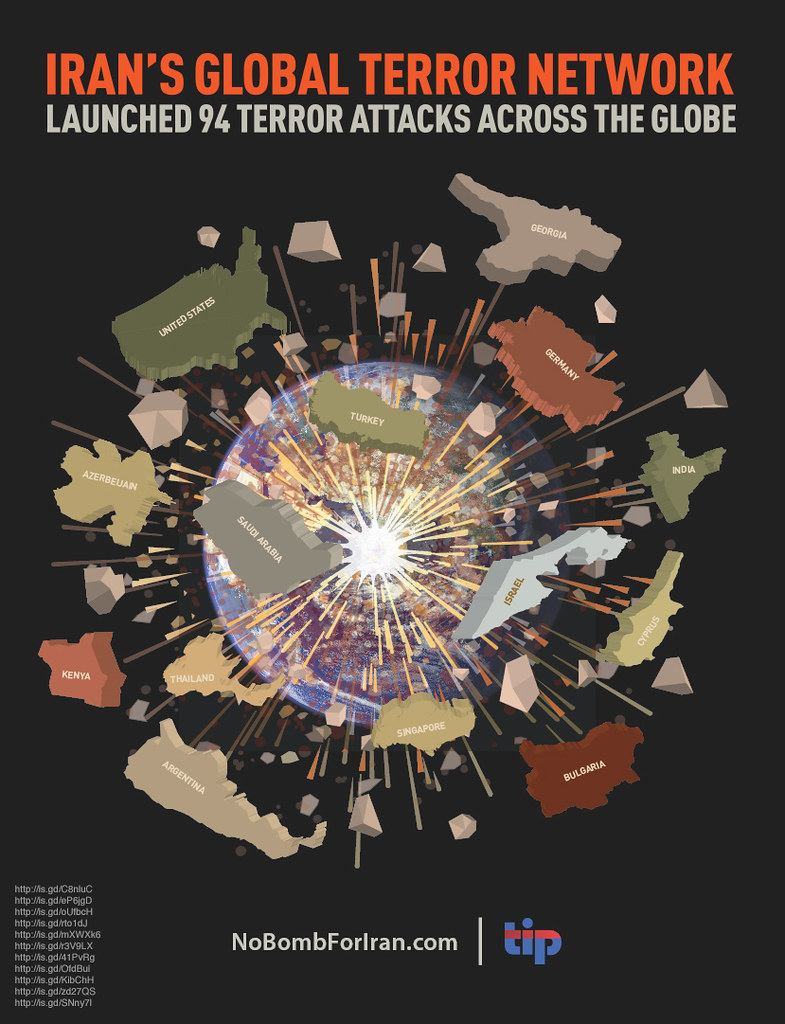

9. **The Shadow of Global Terrorism: Munich and Beyond (Early 1970s)**

The 1970s witnessed a disturbing escalation in the use of terrorism as a political tool, casting a long shadow over international relations and exposing new vulnerabilities in a seemingly interconnected world. The decade opened with a stark demonstration of this emerging threat on September 6, 1970, with what became known as Skyjack Sunday, when Palestinian terrorists hijacked four airliners, taking over 300 people hostage. While the hostages were eventually released, the planes were dramatically blown up, signaling a bold new era of rebellious fighting.

However, it was the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, Germany, that indelibly etched the horror of international terrorism into global consciousness. On September 5, 1972, the Palestinian terrorist group Black September kidnapped and subsequently murdered eleven Israeli athletes. This shocking attack, carried out on a global stage meant to symbolize peace and unity, transformed the perception of terrorism from a localized issue into a pervasive global menace, capable of striking anywhere, anytime.

Beyond these high-profile events, militant organizations across the world increasingly employed terror tactics, highlighting a growing trend of ideological extremism. Groups in Europe, such as the Red Brigades and the Baader-Meinhof Gang, were responsible for a spate of bombings, kidnappings, and murders, particularly targeting political figures and industrialists. Violence continued to plague Northern Ireland and the Middle East, fueled by longstanding ethnic and political grievances.

Even in America, radical groups like the Weather Underground and the Symbionese Liberation Army emerged, although they never achieved the same scale or strength as their European counterparts. The cumulative effect of these incidents underscored the pervasive nature of political violence and the profound challenge it posed to national security and international stability throughout the 1970s, marking a chilling chapter in the decade’s narrative.

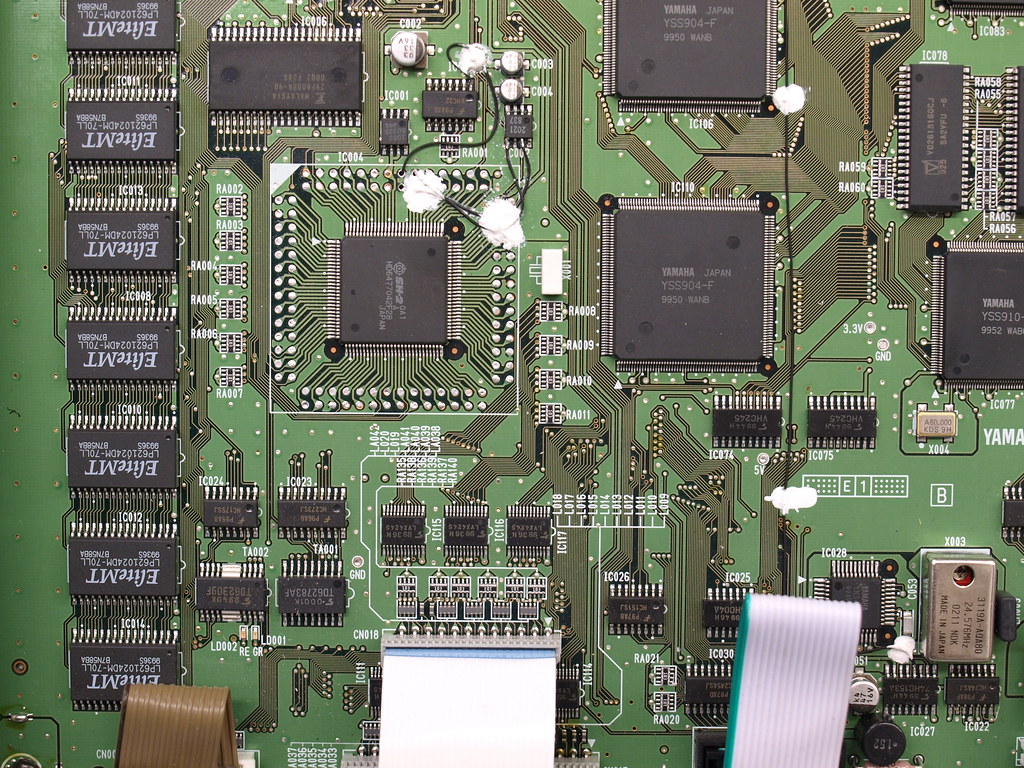

10. **The Digital Dawn: Microprocessors and Quantum Leaps (1970s)**

Amidst the geopolitical turmoil and social upheaval, the 1970s quietly heralded a revolution that would fundamentally transform modern life: the birth of the digital age. This era was characterized by groundbreaking technological and scientific advances, most notably the appearance of the first commercial microprocessor, the Intel 4004, in 1971. This tiny chip marked a profound transformation, initiating the shift of computing units from rudimentary, spacious machines into the realm of portability and home accessibility.

The microprocessor became the engine of innovation, laying the groundwork for personal computers, which would explode in popularity in subsequent decades. Its development wasn’t merely an incremental improvement; it was a paradigm shift that democratized access to computing power, moving it from specialized laboratories and government facilities into the hands of individuals and businesses, thereby fueling an unprecedented wave of digital innovation.

Parallel to these developments in computing, significant advances were made in the realm of theoretical physics. The decade saw the consolidation of quantum field theory, particularly towards its end, thanks to crucial experimental confirmations. These included the confirmation of the existence of quarks and the detection of the first gauge bosons beyond the photon, specifically the Z boson and the gluon. These discoveries were integral components of what was christened in 1975 as the Standard Model.

The Standard Model, representing a profound leap in humanity’s understanding of the fundamental particles and forces that govern the universe, remains the most successful theory describing matter. These scientific breakthroughs, though seemingly abstract, underscored a relentless pursuit of knowledge that ran concurrently with the decade’s more visible conflicts and crises, quietly shaping the future in ways that would only become fully apparent much later.

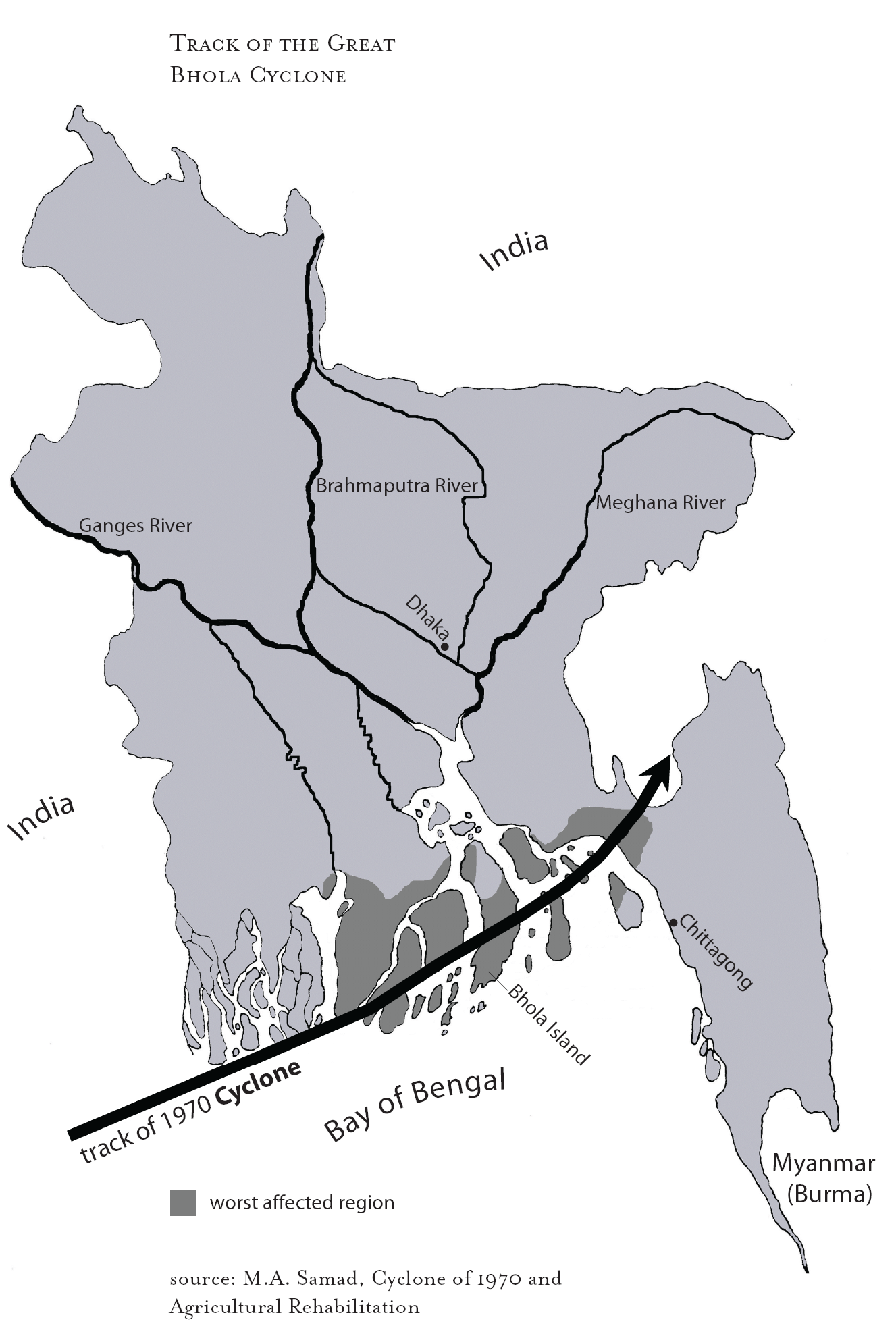

11. **Nature’s Fury: The Decade’s Deadliest Disasters (1970-1976)**

While human conflicts often dominate historical narratives, the 1970s also witnessed a series of natural disasters of staggering magnitude, serving as stark reminders of humanity’s vulnerability to the planet’s raw power. Among these, the 1970 Bhola cyclone stands out as the 20th century’s worst cyclone disaster. In November 1970, this 120 mph (193 km/h) tropical cyclone slammed into the densely populated Ganges Delta region of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), killing an estimated 500,000 people and remaining, to this day, the deadliest tropical cyclone in world history.

The earth itself unleashed immense destructive force during this period. On January 5, 1970, the 7.1 Tonghai earthquake shook Yunnan, China, resulting in between 10,000 and 14,621 fatalities. Just months later, on May 31, 1970, the Ancash earthquake in Peru caused a devastating landslide that buried the town of Yungay, claiming more than 47,000 lives. These seismic events underscored the precarious existence of communities in active geological zones.

Another catastrophic earthquake struck on July 28, 1976, flattening Tangshan, China, in what became one of the deadliest earthquakes of all time. This 7.5 magnitude tremor resulted in the deaths of 242,769 people and injured 164,851, leaving an unimaginable trail of destruction. Similarly, a major earthquake in Guatemala and Honduras on February 4, 1976, killed over 22,000.

These events, alongside the 1971 Odisha cyclone which killed 10,000, and the Bangladesh famine of 1974 which claimed hundreds of thousands, demonstrated the devastating consequences of natural forces compounded by population density and sometimes insufficient infrastructure. They highlighted the urgent need for disaster preparedness and international humanitarian aid, revealing the immense human suffering inflicted when nature unleashed its unbridled power.

12. **Man-Made Catastrophes: From Aviation Tragedies to Nuclear Near-Misses (1970s)**

Beyond natural phenomena, the 1970s were also marred by a disturbing series of human-made disasters and accidents, from unprecedented aviation tragedies to industrial malfunctions, highlighting the inherent risks of burgeoning technological advancement and complex human error. A particularly chilling event was the Jonestown massacre in November 1978, where the Rev. Jim Jones, leader of the People’s Temple, orchestrated a mass murder-suicide of over 900 followers in a remote Guyanese commune, after a visiting Congressional committee and journalists were attacked and Congressman Leo Ryan was killed.

The skies, too, became a stage for catastrophic events. The decade saw some of the worst aviation disasters on record. On March 27, 1977, two Boeing 747s collided on the runway in heavy fog at Los Rodeos Airport in Tenerife, Canary Islands, killing 583 people in the deadliest aviation disaster in history. This single event tragically underscored the critical importance of air traffic control protocols and crew communication, becoming a watershed moment for aviation safety.

Other notable air tragedies included the March 3, 1974, Turkish Airlines Flight 981 crash in France, killing all 346 aboard due to a cargo hatch blowout, and the May 25, 1979, American Airlines Flight 191 incident at Chicago’s O’Hare, where an engine loss during takeoff led to the deaths of all 271 on board and two on the ground, making it the deadliest single-plane crash on American soil. These incidents collectively pushed the aviation industry to re-evaluate and enhance safety standards.

Adding to this somber list was the partial meltdown of the Three Mile Island Unit 2 reactor in Pennsylvania, United States, on March 28, 1979. While ultimately contained, it remains the most significant accident in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant history. This event brought the dangers of nuclear power into sharp public focus, sparking widespread debate about energy policy and safety regulations, and illustrating the profound consequences when human engineering falters.

13. **Africa’s Internal Strife and Dictatorships: Beyond Decolonization (1970s)**

While the 1970s marked significant strides in Africa’s decolonization process, the continent simultaneously grappled with a deeply troubling rise of internal strife, military coups, and brutal dictatorships, often fueled by the power vacuums left by departing colonial powers and Cold War proxy battles. As the context makes clear, Africa was “plagued by endemic military coups, with the long-reigning Emperor of Ethiopia Haile Selassie being removed, civil wars and famine.”

Among the most infamous figures of this era was Idi Amin, who rose to power in Uganda through a 1971 military coup. His brutal dictatorship was characterized by the persecution of opposition and a racist agenda that led to the expulsion of Asians, particularly Indians, from Uganda. Amin’s expansionist ambitions further destabilized the region, culminating in the 1978 Ugandan–Tanzanian War, which ultimately led to his defeat and overthrow in 1979.

Elsewhere, figures like Francisco Macías Nguema ruled Equatorial Guinea as a brutal dictator from 1969 until his overthrow and execution in 1979. Jean-Bédel Bokassa, who had governed the Central African Republic since 1965, took his authoritarianism to an absurd extreme by proclaiming himself Emperor Bokassa I in 1977, renaming his impoverished nation the Central African Empire. He too was overthrown two years later, highlighting the fragility and volatility of post-colonial governance.

These dictatorships and civil wars, such as the Ogaden War (1977-1978) between Somalia and Ethiopia or the ongoing Angolan Civil War which drew in international players, underscored a period of intense instability. They demonstrated that political independence, while a celebrated milestone, often presented a new set of complex challenges in nation-building, governance, and the establishment of lasting peace in a continent still reeling from centuries of external control.

14. **The Iranian Hostage Crisis: A New Geopolitical ‘Wrinkle’ (1979)**

The close of the 1970s saw a dramatic and unsettling new development in global geopolitics, specifically in the Middle East, with the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution introducing a profound and unexpected challenge to the established international order. Following the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s pro-Western monarchy in 1979, Iran transformed into a theocratic Islamist government under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, fundamentally altering the region’s political landscape.

This revolutionary shift was swiftly followed by an event that captured global attention and demonstrated the burgeoning distrust between the new Iranian regime and Western powers: the Iran hostage crisis. On November 4, 1979, 66 diplomats, primarily from the United States, were taken captive and held for an astonishing 444 days. This act of state-sanctioned hostage-taking became a symbol of the revolution’s hostility towards the West and a direct challenge to diplomatic norms.

The crisis profoundly impacted international attitudes, particularly towards the Muslim faith, as global media extensively covered the unfolding drama. It presented the United States with a severe diplomatic and humanitarian challenge, exposing the limits of its traditional foreign policy tools in dealing with a fervent, ideologically driven state that declared itself “hostile to both Western democracy and ‘godless communism’.”

This “new wrinkle” in global geopolitics, as the context describes, marked the rise of Islamic fundamentalism as a potent force on the world stage. It not only solidified existing geopolitical polarizations but also introduced a new, complex player into the international arena, one that would continue to exert significant influence in the decades to come. The Iranian Hostage Crisis truly symbolized the dramatic and unpredictable conclusion to a decade of relentless transformation.

The 1970s, as this comprehensive exploration reveals, was a decade far more complex and impactful than often remembered. It was a crucible where economic shocks, political realignments, and social transformations converged to forge the foundations of the modern world. From the quiet hum of the first microprocessors to the thunderous echoes of distant wars and the profound shifts in global power, the ’70s was a true master of profound change, delivering a relentless series of high-impact events that continue to resonate, reminding us of the enduring legacy of this pivotal era.