The 1970s stand as a monumental decade in film history, a ten-year period that remains astonishing for the sheer quality and artistic bravery of the work emerging from America. It was an era fondly remembered as the “director’s era,” a pivotal moment when filmmakers ascended to unprecedented levels of power, wielding creative control to craft the movies they truly envisioned. This newfound freedom allowed them to explore subjects previously considered taboo, pushing the boundaries of storytelling and cinematic expression in ways that reshaped the industry forever.

Freed from the restrictive constraints of what was deemed acceptable for movie screens, with language now embracing an “anything goes” approach and depictions of nudity and uality becoming remarkably frank, directors seized the opportunity to delve into the raw, unfiltered realities of the human condition. They held their cameras up to society, capturing life with an unflinching gaze, and in doing so, created art that resonated deeply and profoundly. This period saw a convergence of innovative visionaries who, bursting with knowledge of film history and enthralled by the medium, were ready to make their indelible mark.

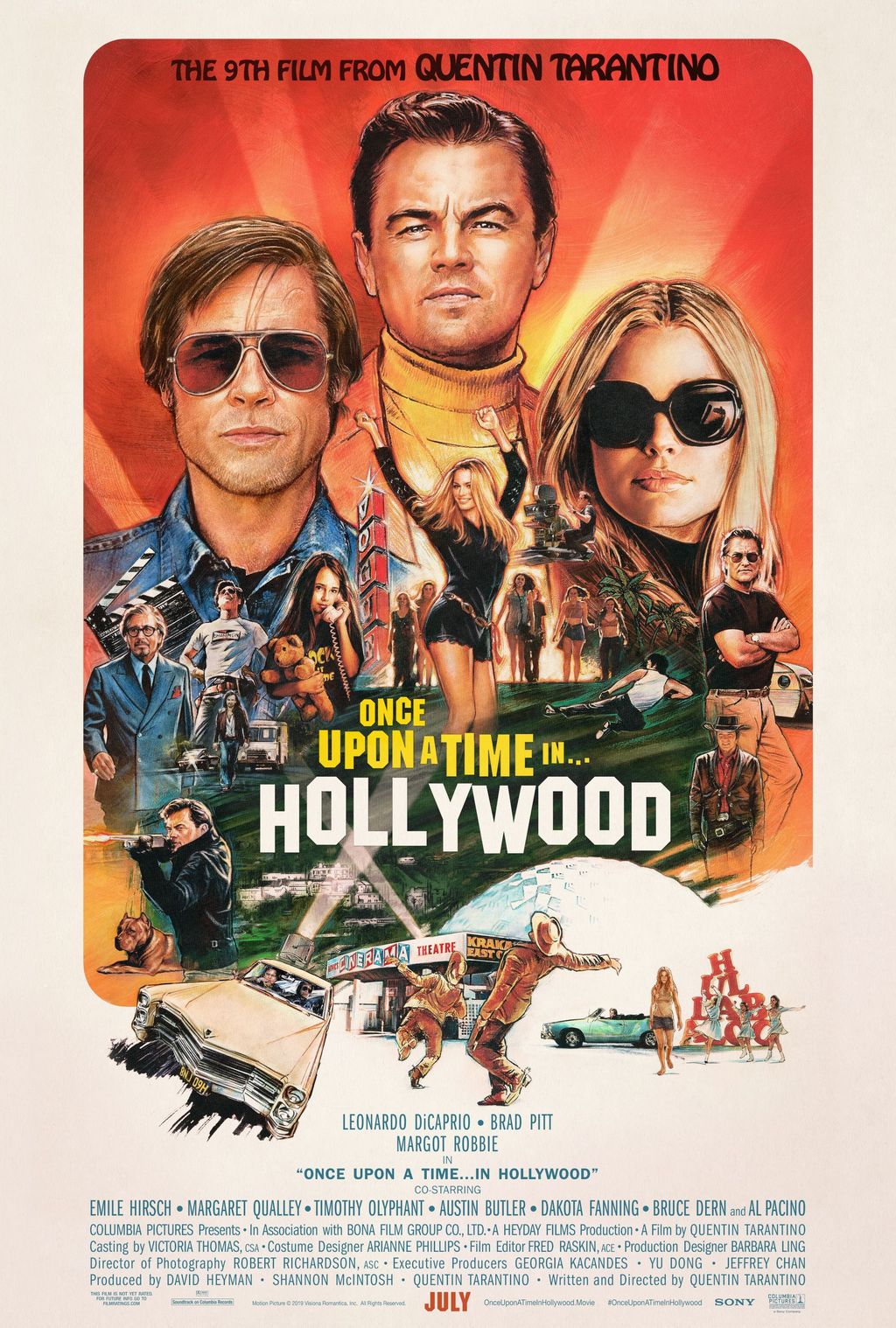

From film school graduates brimming with fresh ideas to seasoned veterans honed in the fast-paced world of television, these directors took Hollywood by storm, dominating the decade and collectively forming a generation of gifted artists often referred to as “the movie brats.” They were a group, the likes of which had rarely been seen before and are unlikely to be seen again, whose passion for cinema was palpable and infectious. In this first part of our exploration, we will turn our gaze to four of these titans: Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Stanley Kubrick, whose unparalleled storytelling prowess defined an unforgettable epoch.

1. Francis Ford Coppola

Francis Ford Coppola’s name is synonymous with the very essence of 1970s cinema, a decade he dominated like no other director in film history. He not only helmed four iconic films during this period, three of which topped critical lists, but also produced ‘American Graffiti’ (1973), which launched George Lucas’s career and sparked a cultural renaissance in 1970s music and clothing. Coppola’s visionary ambition even led him to create his own studio, aspiring to empower young directors to craft their films free from the perceived tyranny of established studios, truly embodying the spirit of the era. His groundbreaking decision to tackle Vietnam as a subject for his next film further underscored his bold, trailblazing approach.

His magnum opus, ‘The Godfather’ (1972), wasn’t just a gangster film; it was, as Coppola himself discovered upon poring over the novel, “a dark metaphor for the American Dream.” It meticulously explored how immigrants, seeking a better life and wealth in America, sometimes found it through the shadowy world of crime. The Corleones, led by the aging but formidable Vito (Marlon Brando), presided over a criminal empire with a chilling fairness, resorting to murder only when his family or interests were gravely threatened. The film masterfully pulls idealistic war hero Michael (Al Pacino), his youngest son, into the family business, transforming him into a figure far more ruthless than his father.

The performances in ‘The Godfather’ are nothing short of legendary. Marlon Brando’s portrayal of Don Vito Corleone, achieved when he was just forty-five, became instantly iconic, a testament to his profound artistry. Al Pacino, as Michael, delivers a remarkable arc of transformation, evolving from a reluctant outsider to a cold, calculating chieftain. The superb supporting cast, including James Caan, Robert Duvall, and Diane Keaton, along with Gordon Willis’s darkly lit cinematography, plunges audiences into the clandestine world where the family’s business, which happens to be crime, unfolds with unsettling intimacy and stark realism.

Then came ‘The Godfather Part II’ (1974), a film that somehow managed to surpass the original, achieving an epic sweep and exploring the overwhelming power and global reach of the Mafia with even greater depth and complexity. Coppola masterfully interweaves narratives from the past and present, showing Vito Corleone’s journey as an immigrant, growing into a man and a powerful crime lord (portrayed brilliantly by Robert De Niro), while simultaneously depicting Michael at the zenith of his power. This dual narrative structure, facilitated by impeccable editing, brilliantly illuminates how absolute power corrupts, allowing us to witness Michael’s gradual loss of his soul, becoming morally dead.

Coppola’s 1970s concluded with the audacious ‘Apocalypse Now’ (1979), a visceral and surreal portrayal of the Vietnam War. From its opening frames, where the serene jungle erupts into an inferno set to Jim Morrison’s mournful crooning of ‘The End’, the audience is plunged directly into the war’s “absolute madness but sensual quality.” Loosely based on Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’, the film follows Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) on a mission to execute the rogue Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), whose descent into madness mirrors the brutal, corrupting essence of the conflict itself. Robert Duvall’s scene-stealing performance as the surfing-obsessed Colonel Kilgore, with his infamous line, “I love the smell of napalm in the morning,” remains a legendary moment in cinema, cementing Coppola’s status as a true visionary who could capture the war with chilling authenticity.

Read more about: Beyond the Screen: 14 Shocking Moments When Hollywood Stars Faced Death Filming Stunts Without CGI

2. Martin Scorsese

Martin Scorsese is widely revered as one of cinematic history’s greatest directors, a master whose powerful storytelling delves deep into the human psyche. His films frequently explore profound themes of guilt, redemption, and moral ambiguity, crafting narratives that resonate with an intense, almost unsettling honesty. Whether he’s navigating the gritty underworld of ‘Goodfellas’ (1990) or the deeply personal and psychologically charged streets of ‘Taxi Driver’ (1976), Scorsese’s oeuvre is consistently defined by complex, often tormented characters and an exceptional understanding of the intricate tapestry of human nature.

‘Taxi Driver’ (1976) stands as a searing indictment of 1970s New York City, a metropolis depicted as a dangerous, crime-ridden hellscape where Times Square teemed with drugs, prostitution, and violence. From the moment we see steam roaring from a sewer grate, as if holding back infernal forces, Scorsese immediately plunges us into this oppressive urban nightmare. Travis Bickle, brilliantly portrayed by Robert De Niro, is a Vietnam veteran suffering from insomnia, taking a job as a night cab driver and witnessing the city’s depravity firsthand. His growing despair and obsession with “cleaning up” the city, fueled by the rejection of a woman and the encounter with a twelve-year-old hooker, Iris (Jodie Foster), propel him towards a violent, desperate resolution.

Scorsese’s genius as a master storyteller lies in his remarkable ability to seamlessly blend raw emotion with stark violence, capturing the agonizing complexities of his characters’ inner lives. In ‘Taxi Driver’, he employs a distinctive narrative style, using voiceovers to reveal Travis’s deteriorating mental state, alongside evocative music and deliberate pacing, to create an immersive and unforgettable experience. His camera becomes a voyeuristic eye, giving the viewer glimpses into Travis’s bizarre mind, making the violence brutal and swift, and the night-life dream-like yet dangerous.

His signature style, characterized by intense character studies, the innovative use of long takes, and a relentless exploration of moral conflict, is vividly showcased in ‘Taxi Driver’. He creates a powerful, almost suffocating atmosphere where the lines between hero and villain blur, and the consequences of moral choices are laid bare. Scorsese’s unique vision not only revolutionized how crime dramas were perceived but also left an indelible mark on cinematic storytelling, demonstrating how film could be a deeply personal and psychologically probing medium.

Read more about: Beyond the Screen: 14 Shocking Moments When Hollywood Stars Faced Death Filming Stunts Without CGI

3. Steven Spielberg

Steven Spielberg’s monumental impact on storytelling in cinema, particularly during the 1970s, cannot be overstated. Alongside George Lucas, he more or less ushered in the era of the modern blockbuster, transforming the industry and audience expectations. Spielberg’s work is characterized by a profound love for movies—both old classics and contemporary creations—and a palpable, lifelong dedication to the art of cinema. He emerged as one of “the movie brats,” a generation of extraordinarily gifted artists whose collective influence would define the decade.

His breakthrough film, ‘Jaws’ (1975), solidified Spielberg’s status as a household name and revolutionized the horror genre. The true genius of the film lies in its masterful restraint: we see astonishingly little of the massive great white shark that terrorizes the East Coast. Due to mechanical shark malfunctions on set, Spielberg famously improvised, showing the attacks primarily from the shark’s point of view, adhering to the adage that “less is more.” This approach intensified the suspense, focusing on the impending attack, its devastating impact, and the chilling aftermath rather than overt gore, creating genuine terror through implication.

The film’s impact was amplified by John Williams’ superb, simplistic yet instantly iconic score, which launched the career of arguably the greatest film composer in history. The performances, particularly Robert Shaw’s as the tough, shark-obsessed Quint, are terrific, lending gravitas to the high-stakes narrative. Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss are equally compelling, yet it is Spielberg’s directorial vision that truly shines, guiding the audience through a gripping tale of man versus nature that remains genuinely terrifying and endlessly rewatchable.

Fresh off the success of ‘Jaws’, Spielberg delivered ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’ (1977), a film that burst with light and wonder, delving into humanity’s first purported contact with benevolent alien beings. The film intricately weaves a narrative where hundreds of ordinary people, including Richard Dreyfuss’s superb “every-man” character, have an unshakable image burned into their minds, drawing them inexorably to Devil’s Tower in Wyoming. The final forty-five minutes of the film are nothing short of breathtaking, unfolding like a divine encounter, filled with awe and majesty. Spielberg fills the screen with a wonder previously unexperienced, culminating in a stunning, peaceful sequence of contact brimming with love and an almost spiritual joy, demonstrating his unparalleled ability to blend spectacle with heartfelt human emotion.

Read more about: 13 Action Films That Crumbled at the Finish Line: When Great Stories Get Betrayed by Their Endings

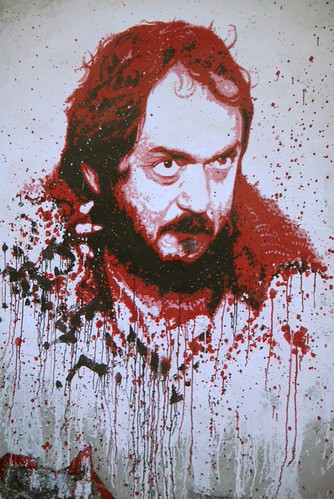

4. Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick was a director who consistently pushed the very boundaries of cinematic storytelling, distinguishing himself through his meticulous attention to detail and his profound exploration of complex psychological and philosophical themes. His films remain some of the most studied and revered in film history, each a testament to his singular vision and unyielding artistic control. From the sprawling cosmic odyssey of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (1968) to the chilling dystopian satire of ‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971), Kubrick fearlessly delved into subjects ranging from the future of humanity to the fundamental nature of violence, establishing himself as an uncompromising auteur.

‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971) stands as arguably the finest film of Kubrick’s career, based on Anthony Burgess’s prophetic novel about a dystopian society in the near future. Even today, decades later, its themes and imagery feel unsettlingly futuristic and disturbingly plausible. The film immediately captivates with the baleful stare of Alex (Malcolm McDowell) in its opening frame, pulling the viewer into his bizarre, violent world. Alex, the charismatic leader of the “droogs,” spends his nights committing acts of violence, pillaging, and rape with a chillingly gleeful smile, embodying a perverse form of freedom.

When Alex is eventually caught and convicted of murder, he undergoes the infamous Ludovico program in prison, a unique aversion therapy designed to cure him of his violent urges by making him physically ill at the thought or sight of harm. Kubrick directs with masterful precision, giving McDowell a jaunty, upbeat demeanor even amidst horrific violence, making Alex one of cinema’s most unsettlingly happy villains. The fight sequences are staged with an almost balletic grace, yet remain shocking and frightening, while the infamous rape sequence, underscored by Alex crooning “Singin’ in the Rain,” is profoundly perverse and unforgettable, forcing viewers to confront uncomfortable truths.

Kubrick’s genius as a master storyteller is rooted in his visual precision and thematic depth, often using the camera itself as a primary storytelling device, allowing images to convey as much, if not more, than dialogue. The always-moving, in-your-face camera work in ‘A Clockwork Orange’ provides an unnerving glimpse into Alex’s bizarre mind, creating a narrative that is both blackly comic and downright scary. His signature style—precision, visual storytelling, and an unwavering exploration of existential themes—is brilliantly showcased here, cementing his legacy as a filmmaker who challenged audiences and redefined the capabilities of the medium.

The 1970s, a period already cemented in cinematic lore, didn’t just give us a handful of visionary directors; it unleashed an entire cohort who redefined storytelling on the big screen. Beyond the monumental works of Coppola, Scorsese, Spielberg, and Kubrick, other maestros were crafting narratives that resonated with profound depth and cultural significance, pushing artistic boundaries in their own unique ways. These filmmakers further solidified the decade’s reputation as a golden age, demonstrating an audacious commitment to storytelling that explored the human condition with unparalleled insight. As we continue our journey through this astonishing era, we turn our gaze to three more directors whose distinct visions left an indelible mark: Milos Forman, Bob Fosse, and Alan J. Pakula, each contributing groundbreaking works that stand as towering achievements in the history of film.

Read more about: Unveiling the Titans: 13 Legendary Directors Who Redefined the Art of Cinema

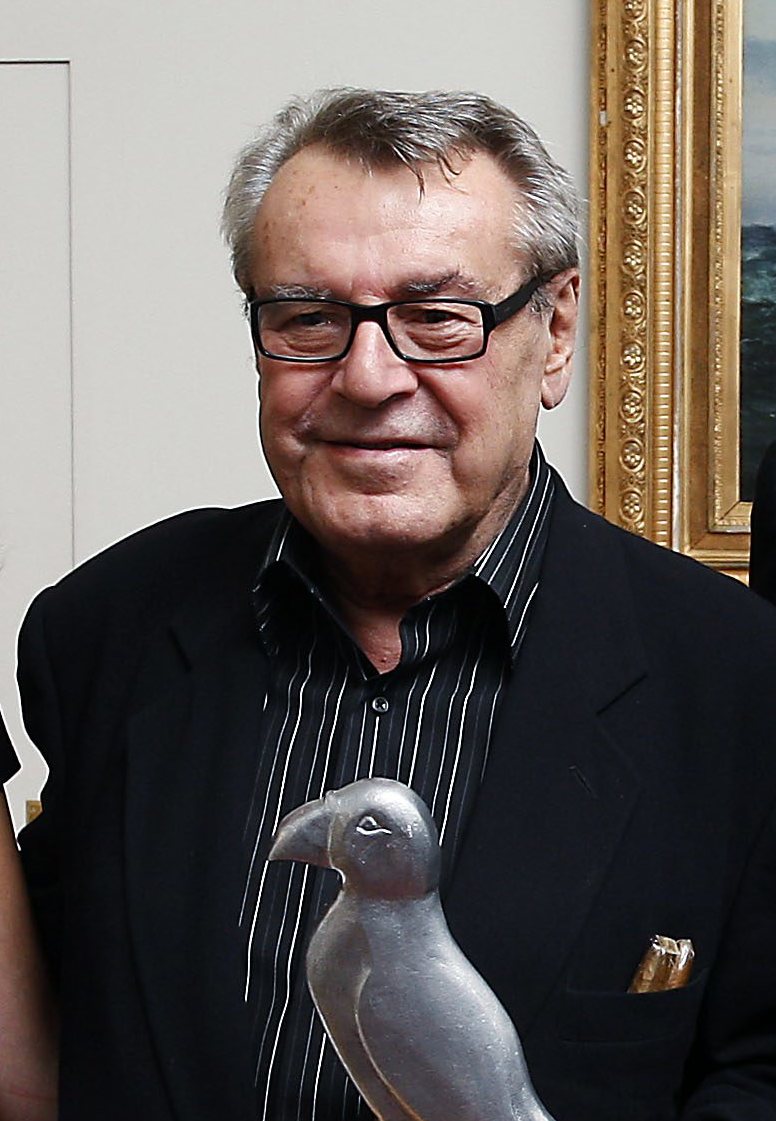

5. Milos Forman

Milos Forman, a Czech filmmaker of extraordinary talent, brought a distinctive, documentary-like European sensibility to American cinema, a quality producer Michael Douglas astutely recognized as essential for the adaptation of Ken Kesey’s powerful novel, ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ (1975). Douglas understood that the right director could elevate the material from merely good to an undeniable masterpiece. Forman’s approach was revolutionary, immersing his cast and crew in a real mental hospital, allowing actual patients to serve as background characters, and even casting the hospital’s head doctor in the film. This daring commitment to authenticity blurred the lines between fiction and reality, imbuing the film with an unsettling realism that few other productions could ever hope to achieve.

At the heart of this profound narrative is Jack Nicholson’s indelible portrayal of Randle McMurphy, a rebellious inmate who feigns mental illness to escape a prison sentence, mistakenly believing a mental institution would offer a cushier existence. McMurphy’s bravado, however, quickly clashes with the oppressive, dehumanizing regimen enforced by Nurse Ratched, portrayed with chilling restraint by Louise Fletcher. He soon learns that his commitment is indefinite, and his fate rests in the hands of the very system he sought to exploit. Nicholson’s performance is nothing short of magnetic, a tour de force that commands every frame, making it impossible to avert one’s gaze from his fiery spirit.

The film masterfully unpacks the profound struggle between individuality and conformity, as McMurphy instigates a quiet rebellion against Nurse Ratched’s authoritarian rule. Her cold, calculated control has, as the narrative poignantly illustrates, metaphorically castrated the male patients, stripping them of their self-esteem and agency. McMurphy’s refusal to submit ignites a spark among his fellow inmates, offering them a glimpse of freedom and humanity they had long lost. While McMurphy’s defiance ultimately leads to his tragic downfall, his spirit, vibrant and unyielding, lives on, allowing each man in his own way to reclaim a part of themselves, to be free and whole once more.

‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ didn’t just captivate audiences; it swept the Academy Awards, clinching the coveted “Big Five” (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Screenplay), a rare feat that underscored its profound impact and critical acclaim. Louise Fletcher, in a role many major actresses shied away from, delivered an Oscar-winning performance, choosing to portray Nurse Ratched not as a caricature of evil, but as a chillingly human figure whose actions are monstrous nonetheless. Forman’s direction, coupled with these legendary performances, created a cinematic landmark that remains one of the greatest American films ever made, a searing exploration of power, control, and the enduring human spirit against institutional oppression.

Read more about: Unpacking the Method: The Extreme Techniques and Divisive Practices of Method Acting That Sparked On-Set Drama

6. Bob Fosse

Bob Fosse, a director whose distinct aesthetic and profound theatricality translated seamlessly to the screen, delivered ‘Cabaret’ (1972), arguably the most remarkable and powerful musical ever committed to film. This groundbreaking work transcended the conventional musical genre, earning eight Academy Awards, including a well-deserved win for Best Director, a testament to Fosse’s visionary leadership. Astonishingly, it remains the film with the most Oscar wins to ever lose Best Picture to ‘The Godfather,’ underscoring its unique critical standing. Fosse directed with an uncompromising blend of “sleaze and ,” yet never once trivialized the incredibly serious undercurrent of its subject matter: the insidious and terrifying rise of the Nazi party in 1930s Berlin as Hitler steadily consolidated his power.

At the heart of ‘Cabaret’ is Liza Minnelli’s electrifying, Oscar-winning, star-making performance as Sally Bowles, the manipulative and hedonistic English singer who navigates the bohemian nightlife of Berlin. Sally’s desperate search for someone to take care of her leads her through a series of relationships, all while the political landscape around her grows increasingly ominous. Minnelli’s portrayal is a tour de force, embodying the alluring decadence and underlying fragility of a society teetering on the brink of profound change. Her vibrant, yet vulnerable, performance anchors the film’s exploration of personal freedoms colliding with escalating political darkness.

Equally unforgettable is Joel Grey’s Oscar-winning turn as the enigmatic Emcee of the Kit Kat Klub. With his grotesque makeup and knowing smirk, the Emcee serves as a chilling allegorical figure, embodying the very essence of evil, sleaze, Nazism, corruption, and decadence that was quietly infiltrating German society. His performances on stage comment wryly and sinisterly on the unfolding political tragedy, often breaking the fourth wall to implicate the audience. Fosse’s masterful directorial choice to restrict nearly all musical numbers to the stage of the cabaret club ensures that these performances act as a direct, unsettling commentary on the deteriorating socio-political climate outside, intensifying the dramatic irony and foreboding atmosphere.

The film’s portrayal of the Nazis’ rise to power is nothing short of haunting, crafted with superb choreography and relentless pacing that mirrors the inexorable march of history. Fosse creates a constant sense of movement and unease, drawing the viewer deeper into Berlin’s vibrant yet doomed nightlife. Perhaps no moment in any musical is more chilling than the scene in the beer garden, where a seemingly innocent, beautiful, blonde, blue-eyed boy begins to sing. As his clear voice swells, joined by an increasing number of impassioned voices, the horrifying realization dawns upon the audience: he is a Hitler Youth, and the song, ‘Tomorrow Belongs to Me,’ is a Nazi anthem. This searing sequence encapsulates the film’s power, cementing ‘Cabaret’ as an unforgettable and profoundly resonant cinematic experience, a stark warning against indifference in the face of burgeoning tyranny.

Read more about: Four Iconic Actresses Depart at 91, Marking the End of an Era

7. Alan J. Pakula

Alan J. Pakula, a director celebrated for his distinctive style within the political thriller genre, achieved a monumental feat with ‘All the President’s Men’ (1976). Based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, this film meticulously chronicled the investigation that ultimately led to the resignation of a recently re-elected President. Pakula’s genius lay in his decision to craft the narrative as a sophisticated detective thriller, a neo-noir infused with an intellectual rigor that brought the intricate world of investigative journalism to vivid, pulse-pounding life. It was a perfect decision that resonated with the era’s hunger for truth and accountability.

Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman deliver compelling, nuanced performances as the tenacious reporting duo, Woodward and Bernstein, respectively. Their on-screen chemistry and unwavering dedication draw the audience into their relentless pursuit of truth. What began as a seemingly isolated story about a simple break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters quickly unravels into a far-reaching conspiracy, revealing the profound depths of corruption within the highest echelons of government. Pakula expertly builds tension, showing the reporters painstakingly piecing together fragments of information, often at considerable personal peril, as they navigate a web of secrets and evasions that threatens to engulf them.

The film is further bolstered by an impeccable supporting cast. Jason Robards, in an Oscar and critics’ award-winning performance, embodies the gruff yet mentoring editor Ben Bradlee with a captivating authority. His terse directives and unwavering support provide a crucial anchor for the reporters. Hal Holbrook’s portrayal of the enigmatic Deep Throat, the anonymous insider who discreetly fed them vital information and kept their investigation on track, is quietly superb, adding layers of intrigue and gravitas. These performances ground the film in realism, making the monumental task of bringing down a sitting President, who had recently won an election by the most one-sided victory in American history, feel utterly believable.

Beyond its gripping narrative, ‘All the President’s Men’ stands as a remarkable historical document. The film’s designers undertook an astounding job of recreating the bustling offices of the Washington Post, transporting viewers back to a time before digital dominance, where the clatter of typewriters and stacks of paper symbolized the engine of news. Watching the film now, the absence of computers is a stark, almost alarming reminder of how quickly technology has evolved, yet the film’s core themes remain timeless. Pakula’s meticulous direction garnered him several critics’ awards for Best Director and the only Oscar nomination for Best Director of his illustrious career. This film is widely regarded as the finest film about journalism ever made, a remarkable and intelligent work that continues to inspire and inform, reflecting the 1970s’ profound commitment to stories of integrity and institutional critique.

Read more about: 14 Iconic Actors Who Publicly Revealed Their Deep Dislike For Their Own Films

The 1970s truly stand as a towering testament to the power of directorial vision and audacious storytelling. From Coppola’s operatic crime sagas to Scorsese’s gritty urban psychodramas, Spielberg’s blockbusters that redefine wonder, Kubrick’s cerebral explorations, Forman’s humane institutional critiques, Fosse’s searing social commentary, and Pakula’s incisive political thrillers, this decade provided a fertile ground for filmmakers to challenge, entertain, and enlighten. These masters, each in their own distinct voice, proved that cinema could be both profound art and powerful cultural mirror. Their indelible contributions continue to resonate, inspiring new generations of filmmakers and reminding us why the 1970s remain an unparalleled epoch in the grand tapestry of cinematic history.