In the glittering annals of Hollywood, the director’s chair has long been considered the throne from which cinematic visions are willed into existence. These auteurs, the architects of storytelling, often preside over their sets like gods, their names synonymous with the distinct aesthetic and narrative soul of a film. Yet, behind the carefully curated glamour and the polished final cuts, lie tales of intense struggle, clashes of titanic egos, and the stark reality that even the most visionary directors can find themselves abruptly removed from their own creations.

This phenomenon, while seemingly a modern by-product of tentpole franchises and brand management, is as old as Hollywood itself. From the very inception of what would become cinematic masterpieces, creative differences, personality conflicts, and a fundamental misunderstanding of a project’s soul have led to abrupt dismissals. These unsavory moments, often shrouded in studio secrecy, were not mere footnotes; they were seismic shifts that irrevocably altered the course of film history, forcing films onto new trajectories and, in some cases, giving birth to legendary works through unexpected hands.

Today, as hundreds of millions of dollars ride on the success of globally branded films, the stakes are higher than ever, making studio executives “more willing to take chances and more willing to make big changes if needed.” We embark on an in-depth journey through the captivating and often tumultuous history of directors who were fired, exploring how these pivotal decisions, often made under immense pressure, reshaped iconic productions and cemented new paradigms for power and artistic control within the industry. Join us as we uncover the fascinating narratives behind these dramatic exits and their lasting legacies on the silver screen.

1. **Richard Thorpe and “The Wizard of Oz” (1939)**Imagine Dorothy from “The Wizard of Oz” with blonde hair and gaudy “baby-doll” makeup. This jarring image, far removed from the beloved cinematic icon we know, was the startling vision of director Richard Thorpe, the initial helmer of the 1939 classic. Thorpe, brought on after Norman Taurog oversaw early tests, quickly found himself at odds with producers who felt he wasn’t imbuing the film with the necessary “air of fantasy.”

His misguided approach extended beyond costume and makeup; he simply “didn’t understand how to film a fairy tale,” as studio heads reportedly concluded. Just two weeks into filming, with the production veering dramatically off course, the studio took swift action. Thorpe was summarily fired, his radical interpretation deemed a fundamental misstep for what was intended to be a heartwarming, fantastical journey.

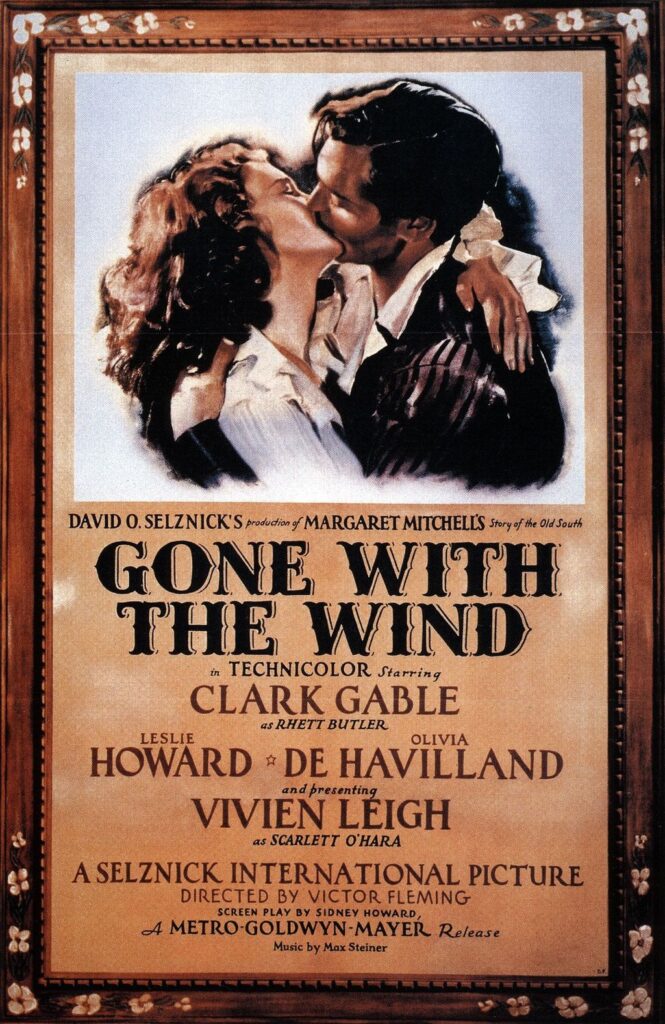

The fallout from Thorpe’s brief tenure was immediate and required extensive damage control. Legendary director George Cukor, already deep in pre-production for “Gone With the Wind,” was brought in temporarily to help redefine the creative direction. Cukor promptly “nixed Dorothy’s original look right away,” steering the film back towards its iconic aesthetic. Though Cukor’s time was short, his intervention was crucial, setting the stage for Victor Fleming to take the reins and guide the film to its eventual, timeless glory.

2. **George Cukor and “Gone With the Wind” (1939)**Even a director of George Cukor’s stature, a filmmaker steeped in the dramatic arts and a master of character development, was not immune to Hollywood’s unforgiving power dynamics. Cukor had painstakingly “shepherded ‘Gone With the Wind’ for producer David O. Selznick for two years of preproduction,” building an understanding that led Selznick to consider him a mentor. Yet, as the film moved into principal photography, Cukor’s burgeoning confidence as a director was perceived as a threat by Selznick.

Adding to the simmering tensions was the formidable star, Clark Gable. Gable, upon discovering Cukor was gay, “suddenly didn’t like Cukor” and reportedly “feared the director might reveal outlandish stories from the actor’s past.” This toxic mix of professional jealousy and personal prejudice created an untenable atmosphere on set, ultimately sealing Cukor’s fate.

Three weeks into filming, with the production already a high-profile spectacle, Cukor “got the boot.” His departure sent shockwaves through the industry, but Selznick quickly replaced him with Victor Fleming – coincidentally, the same director who would also take over “The Wizard of Oz” from Cukor. Despite the drama, “Gone With the Wind” went on to cinematic immortality, a testament to its enduring power, even amidst its turbulent genesis.

Read more about: Marilyn Knowlden Dies at 99: An In-Depth Look at Her Illustrious Child Acting Career

3. **Anthony Mann and “Spartacus” (1960)**Kirk Douglas, a formidable producer-actor, was a man of unyielding vision, especially after missing out on the lead role in “Ben-Hur.” Determined to bring another epic tale of antiquity to the screen, he optioned the novel “Spartacus” and set out to star in and produce it himself. His initial choice for director was Anthony Mann, known for his gritty Westerns like “The Naked Spur,” a genre that had initially “excited Douglas.”

However, Mann’s experience with grand-scale epics proved insufficient. After just “a week on set,” Douglas grew “unsatisfied with his work.” He reportedly mused in his autobiography that Mann “seemed scared of the scope of the picture,” indicating a profound mismatch between the director’s style and the monumental scale of the production. This creative misalignment led to Mann’s swift dismissal.

The brief footage Mann captured for the opening sequence, however, unwittingly “set the style for the rest of the film.” Douglas, having worked with him on “Paths of Glory,” then turned to a young, ascendant talent: Stanley Kubrick. Kubrick’s intervention, a bold move that further cemented his genius, ensured “Spartacus” not only survived its early directorial upheaval but ascended to become “a classic of cinema,” forever etched in Hollywood history.

4. **Steven Soderbergh and “Moneyball” (2011)**The journey of “Moneyball” to the big screen was a testament to perseverance, especially for lead actor Brad Pitt, who championed the project for years alongside director Steven Soderbergh. Soderbergh, an Oscar-winning filmmaker known for his unconventional approach, had a truly “unique vision for the film,” intending a “documentary-like approach” that would even “include interviews with actual MLB players.” This indie sensibility, however, collided head-on with studio anxieties.

Sony Pictures Entertainment, already wary of the film’s “$60 million budget,” grew increasingly uncomfortable with Soderbergh’s “last-minute script rewrites” and his avant-garde documentary style. The studio felt his approach wouldn’t “fly” with such a significant investment. Consequently, on the very day filming was scheduled to commence, Sony “pulled the plug,” halting production and effectively firing Soderbergh.

The film’s fate hung precariously in the balance, but Pitt, unwilling to abandon the project, tirelessly worked to revive it. He collaborated with Sony co-chairman Amy Pascal, enlisting Aaron Sorkin to revise the script and bringing in Bennett Miller, director of “Capote,” to helm the project. Despite the dramatic early setback, “Moneyball” ultimately triumphed, earning “6 Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture,” proving that even a last-minute directorial change can lead to resounding success.

Read more about: Brad Pitt’s Enduring Legacy: A GQ Look at His Most Iconic Roles and Career Milestones

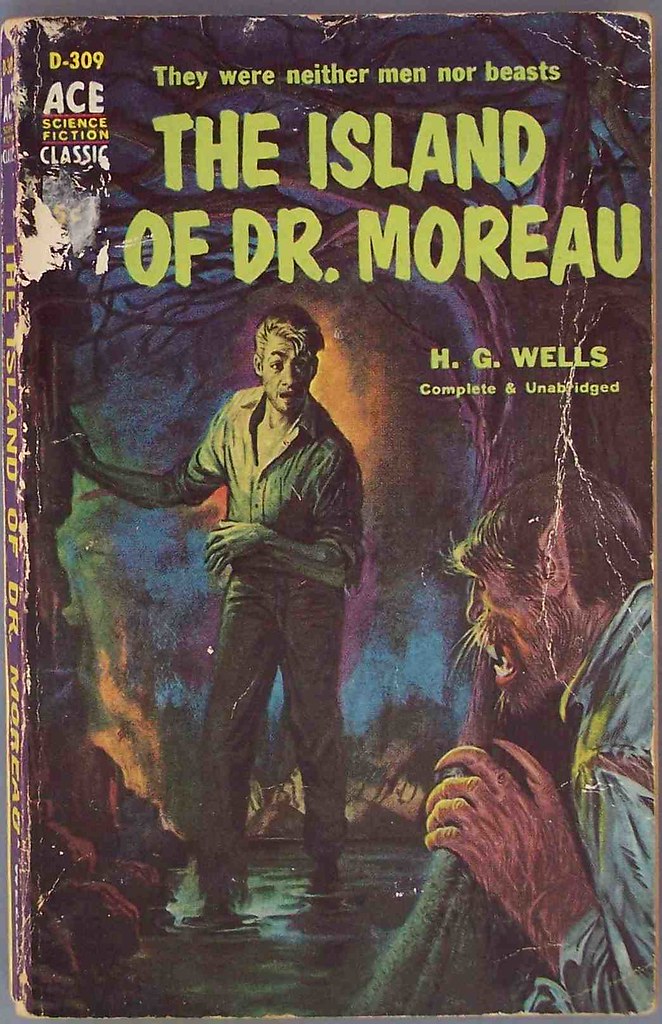

5. **Richard Stanley and “The Island of Dr. Moreau” (1996)**For Richard Stanley, H.G. Wells’s “The Island of Dr. Moreau” was a childhood obsession, a dream project he finally got to realize as his “first major Hollywood production.” He arrived on set with a clear, singular “vision.” Yet, Hollywood’s often brutal reality quickly dismantled his dream. Within “only a week,” Stanley found himself “banned from the set,” a casualty of studio dissatisfaction and an infamously difficult star.

Producers were reportedly unhappy with Stanley’s excessive “focus on the beast creatures,” believing it detracted from the core narrative. More critically, he struggled to manage actor Val Kilmer, who was “notoriously difficult to work with at the time.” These insurmountable challenges led to his abrupt dismissal “via fax,” a particularly callous end to his lifelong ambition.

The saga, however, did not end there. Instead of leaving Australia, where the movie was filmed, Stanley defiantly “hid in the surrounding rainforest and snuck back on set dressed as an extra,” a ghostly presence in the production he was no longer permitted to lead. John Frankenheimer took over, but even his veteran hand couldn’t save the film from becoming “a box office and critical dud,” with Stanley’s nightmare inspiring a 2004 documentary, “Lost Soul.”

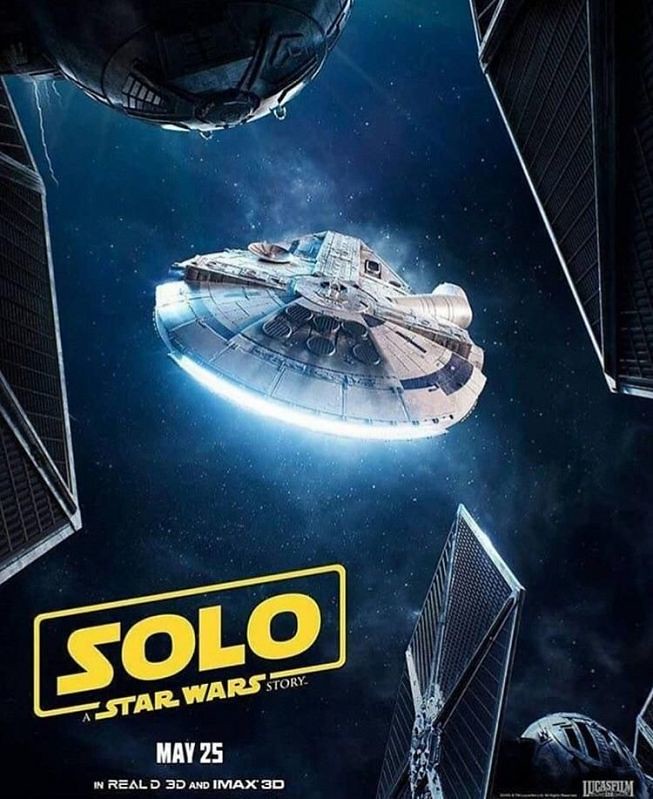

6. **Phil Lord & Christopher Miller and “Solo: A Star Wars Story” (2018)**The promise of a Han Solo origin story from the inventive minds behind “The Lego Movie,” Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, initially sparked excitement across the galaxy. Their unique blend of humor and heartfelt storytelling seemed a perfect fit for the charismatic rogue. However, months into production, “Lucasfilm took issue with the duo’s emphasis on comedy” and their “willingness to let the cast improv,” clashing with co-screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan’s vision.

An anonymous source to Vulture revealed, “‘Phil and Chris are good directors, but they weren’t prepared for Star Wars. After the 25th take, the actors are looking at each other like, ‘This is getting weird.’'” Their directing style was deemed inefficient, especially for a franchise of “Star Wars'” magnitude, leading to their unprecedented firing deep into filming.

Ron Howard, a veteran filmmaker and “George Lucas protégé,” was swiftly “handed the Falcon’s keys,” tasked with “reshotting nearly 70%” of the film. While “Solo” didn’t receive scathing reviews, it was widely perceived as “remarkably average” and marked “the franchise’s first financial letdown.” The episode highlighted the growing studio preference for “brand managers” over auteurist visions, especially within the confines of established intellectual property, a lesson that resonated profoundly throughout Hollywood.

7. **Richard Donner and “Superman II” (1980)**Richard Donner, the visionary behind the groundbreaking “Superman” (1978), embarked on an ambitious endeavor to film both “Superman” and “Superman II” back-to-back. With 75% of the sequel already completed, and having delivered a cinematic triumph with the first film, it seemed natural that Donner would return to finish his work. Yet, the escalating costs and intense behind-the-scenes “tensions on set” with producers Alexander and Ilya Salkind created an irreparable rift.

Despite his substantial contributions and the critical success of his initial “Superman” film, Donner was controversially “replaced with Richard Lester.” Due to stringent Directors Guild of America rules, Lester was compelled to reshoot a significant portion of the sequel to secure full directing credit. While some of Donner’s original scenes remained in the final cut due to budgetary and scheduling constraints, the film that reached theaters was largely Lester’s vision.

Years later, in 2006, fans were finally given the opportunity to witness Donner’s original intent with the release of his re-edited director’s cut, “Richard Donner’s version of Superman II.” This revelation unveiled “an entirely different version of the film,” underscoring the profound impact a change in directorial hands can have, even when much of the foundational work has already been laid. It served as a potent example of how studio politics can overshadow artistic continuity.

The narratives of directorial dismissal, far from being confined to Hollywood’s golden age, have evolved into a complex interplay of artistic vision, formidable celebrity influence, and the ever-tightening grip of studio control, especially within the contemporary landscape of blockbuster franchises and high-stakes prestige dramas. As cinematic endeavors became global brands, the director’s autonomy has frequently found itself on a collision course with corporate strategy, forging a new set of rules for the industry’s most powerful creatives.

This modern era of filmmaking, characterized by astronomical budgets and the immense financial pressure on globally branded properties, sees executives often act less as creative patrons and more as brand managers. The stakes are higher than ever, and the willingness to make radical changes, even if it means dismissing a director mid-production, underscores a fundamental shift in how artistic control is navigated. These subsequent cases reveal the multifaceted reasons behind such dramatic exits and their profound impact on the films that ultimately reached the silver screen.

Read more about: Flying High: These 14 Superman Movies Are So Good, They’re Practically Perfect!

8. **Bryan Singer and “Bohemian Rhapsody” (2018)**In the realm of biographical dramas, the journey to a compelling screen portrayal often carries its own unique set of challenges, and for ‘Bohemian Rhapsody,’ the path was notably turbulent. While the opening credits unequivocally name Bryan Singer as the director, the reality behind the camera was a far more fragmented story, a testament to the internal struggles that can plague even highly anticipated productions.

Reports from the set indicated significant friction between Singer and the film’s star, Rami Malek, whose dedication to embodying Freddie Mercury was unwavering. These clashes, coupled with Singer’s alleged habitual lateness to set, began to fray the production’s fabric. The situation reached a critical point in late 2017 when Singer simply failed to appear for work, citing a sick mother, leaving the studio with a significant portion of the film still unshot.

With over two weeks of principal photography remaining, the studio made the decisive move to fire Singer, an action that sent ripples through the industry. Dexter Fletcher was swiftly brought in to complete the film, navigating the complex task of finishing a project under immense pressure. Despite Singer’s controversial departure and subsequent legal troubles, he maintained sole directing credit due to stringent DGA rules. The film went on to achieve immense commercial success, capturing multiple Academy Awards, though notably, Singer’s name was conspicuously absent from any of the acceptance speeches, a silent acknowledgement of the film’s complicated genesis.

9. **Edgar Wright and “Ant-Man” (2015)**For years, the prospect of an ‘Ant-Man’ film directed by Edgar Wright, the visionary behind ‘Scott Pilgrim vs. the World,’ had film enthusiasts buzzing with anticipation. Wright’s distinctive blend of humor, dynamic action, and idiosyncratic storytelling seemed an ideal match for the quirky superhero, and he had been attached to the project for over a decade, meticulously developing its narrative and visual style.

However, as the film progressed towards production, a chasm began to form between Wright’s singular artistic vision and Marvel Studios’ increasingly stringent brand management. This became a classic case of clashing creative philosophies within the confines of a major cinematic universe. As Wright himself succinctly articulated in a *Variety* interview, “I wanted to make a Marvel movie but I don’t think they really wanted to make an Edgar Wright movie,” highlighting the growing tension between auteurist expression and franchise conformity.

Ultimately, just weeks before filming was set to commence, Wright departed the project, a decision that deeply disappointed fans and industry observers alike. Peyton Reed was swiftly installed as the new director, tasked with steering the film to completion while adhering to the established Marvel template. Despite receiving screenplay and story credits, Wright has openly admitted that he has never been able to bring himself to watch the final film, a poignant reflection on the compromises often demanded when individual artistry confronts the colossal machinery of intellectual property, yet he reportedly holds no hard feelings towards the studio.

10. **Zack Snyder and “Justice League” (2017)**The journey of ‘Justice League’ to the screen is perhaps one of the most publicly scrutinized and dramatically altered productions in recent memory, epitomizing the complex intersection of personal tragedy, studio intervention, and fan advocacy. While initial rumors suggested Zack Snyder had been fired, his departure from the film was, in fact, due to the devastating loss of his daughter, a deeply personal tragedy that prompted him to step away from the demanding production.

In Snyder’s absence, Joss Whedon was brought in to oversee post-production and extensive reshoots. However, Whedon’s known for his ‘quippy style’ and lighter tone, proved to be a stark contrast to the darker, more mythic aesthetic that Snyder had painstakingly established for the DC Extended Universe. This stylistic divergence, combined with Whedon’s alleged on-set behavior, alienated many of the cast and crew, contributing to a final theatrical cut that was widely criticized as disjointed and, ultimately, a certified box office bomb.

The film’s critical and commercial failure fueled an unprecedented fan movement, passionately advocating for the release of Snyder’s original vision, the so-called “Snyder Cut.” This fervent campaign, leveraging social media and direct appeals, ultimately succeeded years later, leading Warner Bros. to greenlight Snyder’s return to complete his four-hour epic, ‘Zack Snyder’s Justice League.’ This monumental effort, widely considered by fans to be the definitive version, underscored the profound impact a director’s cohesive vision can have and the enduring power of audience demand in shaping a film’s legacy.

It also highlighted a significant evolution in Hollywood’s power dynamics: while studios hold immense sway over branded intellectual property, the collective voice of a dedicated fanbase can, under extraordinary circumstances, challenge and even overturn executive decisions. Snyder’s experience became a powerful narrative of redemption for an artist whose personal circumstances intersected with creative disputes, ultimately allowing his original artistic intent to be fully realized, albeit years later.

11. **Tony Kaye and “American History X” (1998)**’American History X,’ a searing drama that remains a powerful cultural touchstone, is another potent example of the fraught relationship between a director’s artistic autonomy and studio prerogatives. For Tony Kaye, it marked his feature film debut, and he delivered his initial cut of the movie within the stipulated timeline and budget, confident in his artistic choices.

However, New Line Cinema, the studio behind the film, found Kaye’s first version to be unsatisfactory. Kaye then submitted a shorter cut, but this too failed to meet the studio’s expectations, leading to an intractable dispute over the final shape of the film. Frustrated with Kaye’s perceived inflexibility, the studio eventually took the drastic step of dropping him and creating their own edit of the movie, fundamentally altering his original vision.

A disgruntled Kaye publicly disowned the studio’s cut and attempted, fiercely but unsuccessfully, to have his name removed from the project, a testament to his profound disagreement with the final product. Despite his strenuous objections and the deeply personal nature of his work, DGA rules dictated that he would still receive directorial credit. The saga surrounding ‘American History X’ remains a stark illustration of the often-unbridgeable gap between a director’s uncompromised artistic vision and a studio’s commercial and narrative demands.

12. **Alex Cox and “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” (1998)**The adaptation of Hunter S. Thompson’s iconic, drug-fueled odyssey, ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,’ was always destined to be a challenging cinematic undertaking, attracting its own share of behind-the-scenes drama. Alex Cox was initially slated to direct, having even adapted the screenplay from Thompson’s 1971 novel. However, his tenure proved to be brief and notably contentious, highlighting how profoundly personal dynamics can derail a high-profile project.

Cox’s creative differences extended beyond the script to a rather infamous and ‘unsavory meeting’ with Thompson himself in 1997. The legendary author reportedly took issue not only with Cox’s script alterations but was also personally insulted by Cox’s refusal to watch football – a beloved Thompson pastime – and his vegetarianism, which led him to decline Thompson’s homemade sausage. This clash of personalities and visions created an untenable situation, quickly compounded by disagreements with star Johnny Depp and producer Laila Nabulsi.

The cumulative effect of these disputes led to Cox’s swift replacement by the idiosyncratic visionary Terry Gilliam, who, along with Tony Grisoni, rewrote the script. Despite the overhaul, Cox and Tod Davies retained co-writing credits for their initial contributions. The story of Cox’s departure from ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ underscores the unique challenges of adapting cult classics and working with larger-than-life personalities, where creative clashes can extend far beyond the screenplay pages.

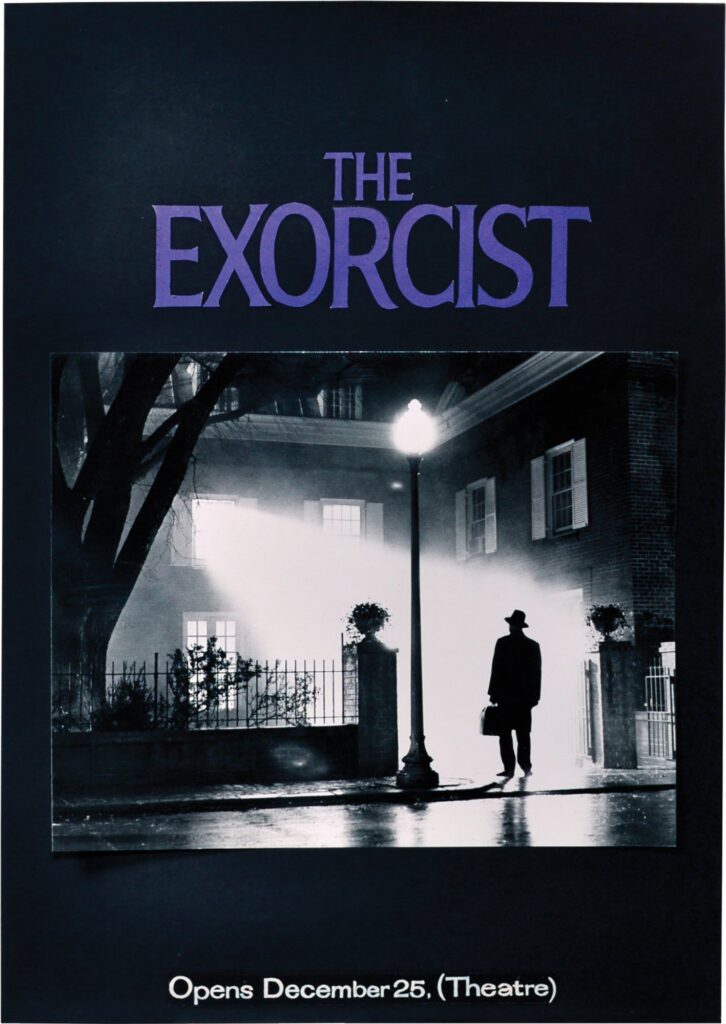

13. **Paul Schrader and “Exorcist: The Beginning” (2004)**The prequel to ‘The Exorcist’ faced an extraordinarily convoluted path to the screen, becoming a textbook example of studio second-guessing and the ultimate challenge to a director’s completed work. Paul Schrader, a director known for his profound and often dark psychological dramas, was originally entrusted with the project and went so far as to complete his version of the film. His artistic integrity and distinct vision guided the production through its entirety.

However, the studios behind the film, upon reviewing Schrader’s finished product, found it to be unsatisfactory. They deemed his take insufficiently terrifying or perhaps too cerebral for a mainstream horror prequel. In a rare and drastic move, they opted to scrap Schrader’s completed version entirely. They then brought in Renny Harlin, a director known for more commercially oriented action and horror films, to helm a new version, astonishingly utilizing the same cast and nearly the same script, aiming for a different tone and more conventional scares.

What became ‘Exorcist: The Beginning’ largely flopped at the box office, failing to resonate with critics or audiences. This commercial disappointment led to an unexpected turn of events: the studio, in a remarkable act of contrition, returned to Schrader, offering him the opportunity to complete his original cut. This version was eventually released as ‘Dominion: Prequel to the Exorcist.’

While Schrader’s ‘Dominion’ only performed slightly better, its very existence as a director’s cut released after the studio’s re-do highlights the precarious nature of artistic vision in Hollywood, where even a completed film can be dismantled and reassembled. It raises fundamental questions about studio confidence, the elusive nature of commercial appeal, and the challenging compromises inherent in bringing a horror legacy to new life.

14. **John Avildsen and “Saturday Night Fever” (1977)**Fresh off his triumphant, Oscar-winning success with ‘Rocky’ in 1976, director John Avildsen was seemingly poised for another hit when he was signed on to direct ‘Saturday Night Fever’ the following year. The disco-era drama, starring the burgeoning icon John Travolta, presented a prime opportunity for Avildsen to follow up his acclaimed work. Yet, despite his recent accolades, his tenure on the project proved to be unexpectedly short-lived.

Avildsen quickly found himself embroiled in numerous script disputes with producer Robert Stigwood. The core of the disagreement stemmed from Stigwood’s belief that Avildsen was trying too hard to mold the film’s lead, Tony Manero, in the image of Rocky Balboa. Travolta himself later alluded to this, suggesting that Avildsen envisioned Tony as a more ‘nice guy’ character, a stark departure from the raw, complex, and sometimes morally ambiguous persona required for the role.

This fundamental difference in character interpretation and overall tone proved to be an insurmountable obstacle. Consequently, just three weeks before filming was even scheduled to begin, Avildsen was abruptly fired from the project. His early dismissal from ‘Saturday Night Fever’ serves as a crucial reminder that creative differences, particularly concerning the very essence of a film’s protagonist, can lead to a director’s removal even before a single frame is shot, underscoring the delicate balance of creative control.

The ever-shifting sands of Hollywood’s power landscape continue to redefine the director’s role, particularly in an age where intellectual property reigns supreme and audiences wield unprecedented influence through digital platforms. From the legendary figures of early cinema grappling with studio moguls to modern auteurs navigating the complex demands of branded franchises, the tales of directorial exits are not mere industry gossip; they are vital chronicles of an art form perpetually caught between singular vision and collective enterprise. These narratives underscore a persistent truth: the path to cinematic glory is often paved with creative battles, profound compromises, and the unwavering conviction that, sometimes, rewriting history means changing the hands that guide the lens.