Humanity’s journey is a tapestry woven with threads of ingenuity, foresight, and relentless ambition. Across centuries, inventors, engineers, and visionary thinkers have consistently pushed the boundaries of what’s possible, ushering in eras of unprecedented advancement. From the intricate gears of early mechanisms to the foundational theories of modern computing, these individuals have laid the groundwork for the seamless, technologically rich society we inhabit today.

Yet, the narrative of innovation isn’t always one of immediate triumph and recognition. For some of the most profound minds, the fruits of their labor ripened long after they had departed the world stage. Their dreams, sometimes sketched in rough notebooks, sometimes halted by a lack of resources or public understanding, or tragically cut short by untimely demise, often required the passage of years, even decades, to fully materialize and integrate into the public sphere. It is a testament to the power of a truly revolutionary idea that it can outlive its originator, eventually reshaping industries and daily lives in ways its creator could only have imagined.

In this deeply insightful exploration, we delve into the stories of ten such remarkable tech pioneers. These are the individuals whose groundbreaking inventions and bold visions didn’t just survive their creators’ absence but flourished, ultimately becoming cornerstones of progress. Their legacies serve as powerful reminders that true innovation often plays out over the longest timelines, a slow burn that eventually ignites a brighter future for generations to come. Join us as we uncover the fascinating tales of those who sowed the seeds of tomorrow, never knowing the magnitude of the harvests they enabled.

1. **Henry Mill’s Typewriter**In the early 18th century, amidst the burgeoning industrial revolution, an English engineer named Henry Mill, who worked for the New River Company, conceived of an invention that would fundamentally alter the act of writing. In 1714, he secured a patent for what he vaguely described as “an artificial machine or method for the impressing or transcribing of letters singly or progressively one after another.” While the specifics of his design remain elusive, historians widely recognize this as the earliest known conceptualization of what we now understand to be the typewriter.

Mill’s vision, however, far outpaced the technological capabilities and perhaps even the perceived needs of his era. Despite his patent and the revolutionary nature of his proposal, he never managed to mass-produce the machine, nor did he even construct a working prototype. He passed away in 1770, leaving his groundbreaking idea as a mere blueprint, a tantalizing glimpse into a future he would never personally witness.

Decades later, Mill’s underlying concept found a new purpose and renewed interest. The challenge of aiding blind individuals in communication sparked a search for mechanical writing aids, and his foundational idea began to spread beyond its initial conceptual confines. This trajectory highlights how an initial spark, even if not fully realized, can ignite a chain of innovation across different societal needs.

Leaping forward to 1843, Charles Thurber built a machine with a similar purpose, yet he too failed to call it a typewriter and did not live to see it widely adopted. It wasn’t until 1873, more than a century after Mill’s death, that two Americans, Christopher Sholes and Carlos Glidden, finally succeeded in producing what we recognize as the modern typewriter. Their design drew upon these earlier, foundational concepts, ultimately bringing Mill’s distant dream into tangible reality, revolutionizing written communication, and setting the stage for every keystroke we make today.

2. **Robert Fulton’s Steam Warship**Robert Fulton, already a respected innovator in engineering circles, embarked on what was intended to be his crowning achievement in 1814: the design of an extraordinary warship named the USS Demologos. This vessel represented a monumental leap in American naval technology, marking the advent of the first steam-powered warship in the U.S. Navy. It was a concept born of strategic necessity and visionary engineering, poised to redefine naval warfare.

Fulton’s design for the Demologos was nothing short of revolutionary. He envisioned a heavily armed and fortified vessel, encased in thick armor, a seemingly impenetrable floating fortress. Its unique structure featured two hulls with a massive paddlewheel strategically positioned between them. One hull housed a powerful steam engine, while the other contained its equally massive boilers, creating a balanced yet formidable war machine stretching over 48 meters (157 feet) in length and displacing an impressive 2,475 tons. This configuration was explicitly designed for the robust defense of American waters against contemporary artillery threats.

Tragically, fate intervened before Fulton could see his masterpiece completed. In 1815, in a heroic act of selflessness, he plunged into the icy waters of New York’s Hudson River to rescue a friend. The subsequent exposure led to pneumonia, and Fulton succumbed to the illness shortly thereafter, his grand vision still underway. It’s a poignant reminder of the personal cost sometimes borne by those who dare to innovate.

Despite his passing, work on the Demologos pressed on. The ship was eventually completed and, in a fitting tribute, renamed the USS Fulton. However, destiny had another twist: it never saw combat, having been launched just after the conclusion of the War of 1812, the very conflict it was designed to defend against. Its remarkable, albeit brief, existence ended tragically in 1829, when a gunpowder explosion destroyed the vessel. Nevertheless, its pioneering design irrevocably altered the trajectory of naval engineering, solidifying Fulton’s legacy as a true visionary.

3. **Alan Turing’s Automatic Computing Engine**The immediate aftermath of World War II saw the dawn of the computing age, a period marked by both immense promise and significant practical hurdles. Early computers were monumental in size, astronomically expensive, and strictly limited to performing highly specific tasks. It was within this challenging landscape that the brilliant British mathematician, Alan Turing, stepped forward with a concept that would redefine the very architecture of computation.

In 1945, Turing proposed the radical design of an electronic stored-program general-purpose digital computer, a vision far ahead of its time. The following year, he formally presented his detailed report to the UK’s National Physical Laboratory (NPL). The NPL recognized the profound potential of his concept and, inspired by his insights, enthusiastically launched the project the year after that, in 1947.

The computer Turing designed, known as the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE), was groundbreaking in its logical principles. These principles diverged significantly from the transistor-based machines that would dominate later decades, showcasing Turing’s unique approach to problem-solving. He dedicated several intense months to the project, laying down its foundational architecture, before moving on. His departure left subsequent NPL technicians grappling with the intricate complexities of his design, puzzled by the advanced methodologies required to proceed.

By 1950, engineers successfully completed a pilot model of the ACE. It proved remarkably fast for its era, though it didn’t fully embody the expansive scope of Turing’s original vision. Tragically, Alan Turing died in 1954, never witnessing the complete realization of his monumental project. The first full-scale ACE, a pivotal milestone in the history of computing, was finally finished in 1957, three years after his passing, a testament to an intellect that reshaped the digital world before its true dawn.

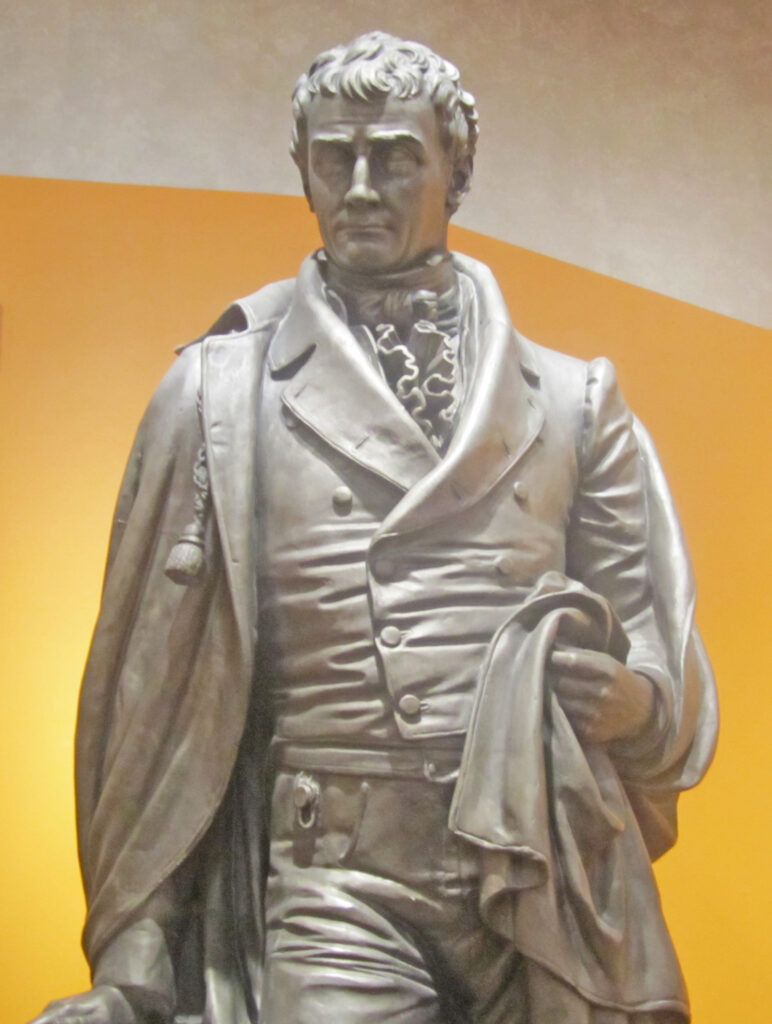

4. **Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Clifton Suspension Bridge**Isambard Kingdom Brunel stands as a colossus of 19th-century Britain, revered as nothing less than the father of civil engineering. His career was characterized by audacious projects and an unwavering commitment to innovation. At the remarkably young age of 24, in 1830, Brunel was appointed the project engineer for a monumental task: to construct a bridge spanning the River Avon in Bristol. From its inception, this endeavor was fraught with challenges, including repeated rejections of his designs and the immense breadth of the river, which severely tested the limits of contemporary technology.

Brunel’s chosen design for the Clifton Suspension Bridge was revolutionary, destined to feature the longest span of any bridge in the world at the time of its conception. This bold vision, however, faced relentless obstacles. The project was plagued by protracted delays, stemming from both engineering complexities and persistent financial difficulties, often a perilous combination for ambitious infrastructure endeavors. These setbacks underscored the immense scale of his ambition and the nascent state of the technologies he sought to employ.

Sadly, Brunel, a heavy smoker throughout his life, succumbed to a stroke in 1859, passing away before he could witness the grand completion of his most iconic bridge. It was a poignant end for a man whose vision had literally spanned distances. Yet, his pioneering plans were so robust and forward-thinking that they remained foundational. The construction continued, driven by the indelible blueprint he had created.

The bridge was finally completed in 1864, serving as a magnificent, tangible tribute to his unparalleled brilliance. Today, it endures as an engineering marvel, measuring an impressive 702 feet (214 meters) in length, with its two distinctive 85-foot (26-meter) towers rising majestically 249 feet (76 meters) above the river below. Its remarkable stability continues to inspire and impress modern engineers, a silent, enduring monument to Brunel’s genius, even though he never lived to see its triumphant success and lasting impact.

5. **Galileo Galilei’s Pendulum Clock**Galileo Galilei, the famed Italian astronomer and mathematician, dedicated his life to unraveling the mysteries of the natural world. Among his numerous groundbreaking discoveries was a particularly remarkable observation concerning the motion of pendulums: he found that the swinging period of a pendulum remains constant, irrespective of the arc it travels. This insight was counter-intuitive to the prevailing understanding of the time, yet it became a foundational principle in physics, particularly crucial for comprehending harmonic oscillation and cyclical motion.

As Galileo approached the twilight of his life, nearly blind and 77 years old, his mind remained fertile with innovation. It was during this period that he meticulously outlined how a pendulum could be effectively utilized to regulate the mechanism of a clock, proposing a revolutionary advancement in timekeeping. His son, Vincenzo, attempted to translate his father’s detailed schematics into a working device, but despite his efforts, he was unsuccessful. Galileo died in 1642, his brilliant concept for a pendulum clock still an unfulfilled dream, a theoretical masterpiece yet to be brought into mechanical existence.

Fourteen years later, in 1656, the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens, deeply inspired by Galileo’s comprehensive notes and theoretical insights, successfully constructed the world’s very first working pendulum clock. Huygens’ achievement was a direct realization of Galileo’s genius, a testament to the clarity and accuracy of the Italian polymath’s original observations and principles. It demonstrated how profound theoretical understanding can lay the groundwork for practical, transformative inventions, even across different minds and generations.

This invention heralded a new era in timekeeping, revolutionizing accuracy and precision in measurement, and simultaneously advanced the scientific study of motion in an unprecedented way. While Galileo never lived to witness the physical completion and widespread impact of the pendulum clock, his singular insight into the consistent rhythm of the pendulum provided the essential beat that has, quite literally, kept the world ticking ever since, a silent architect of precision across the ages.

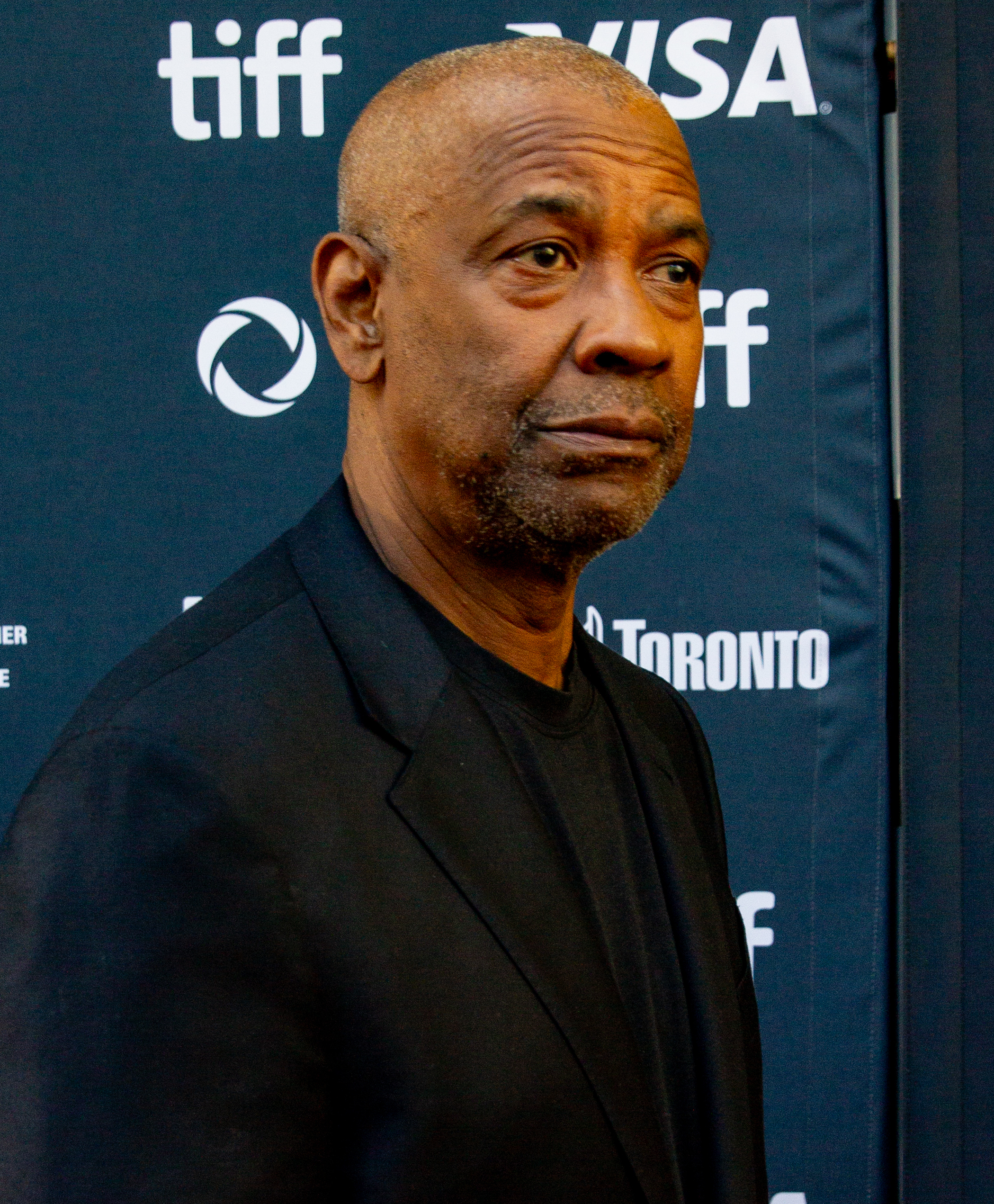

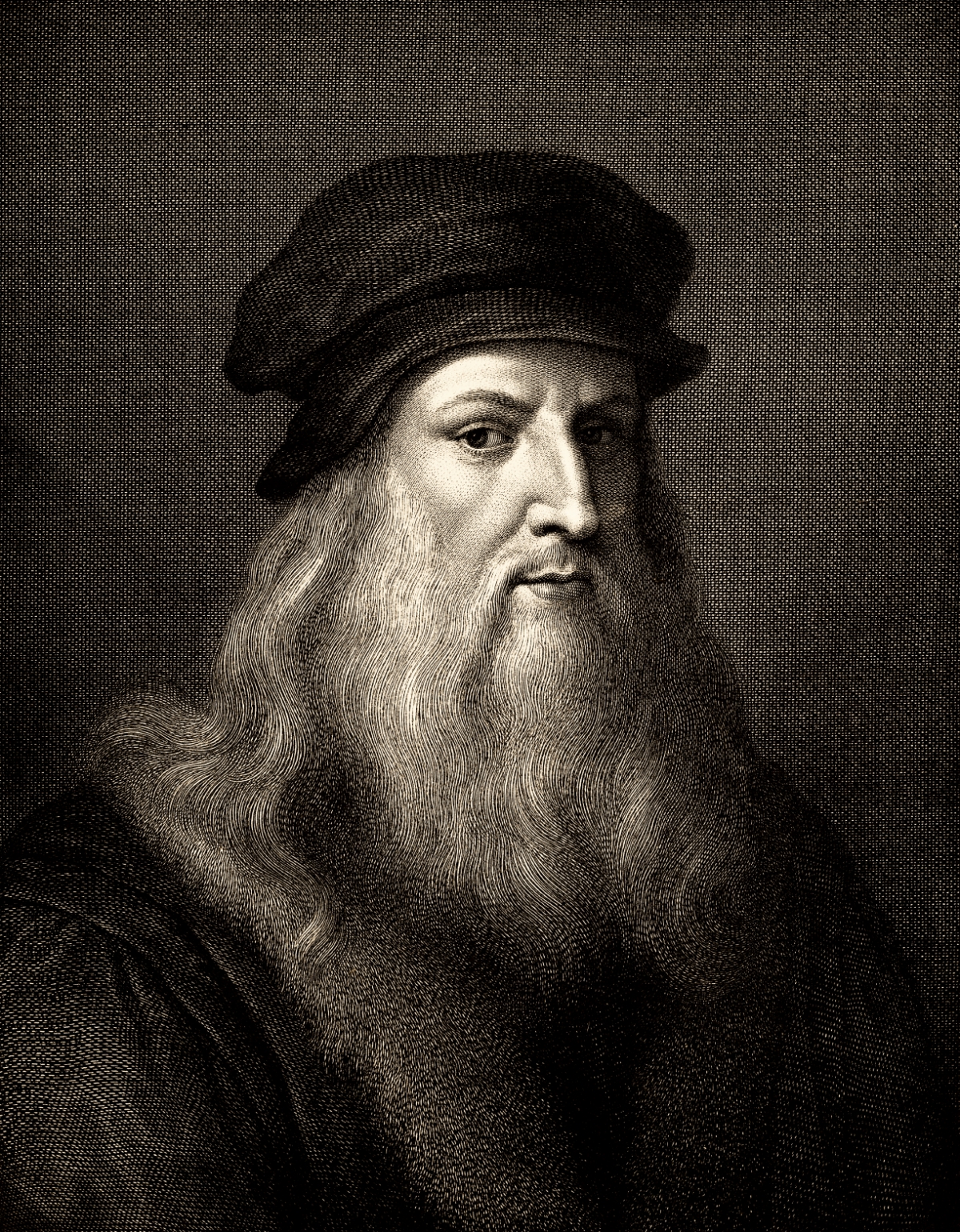

6. **Leonardo da Vinci’s Viola Organista**Leonardo da Vinci, a mind that famously “never rested,” transcended the conventional boundaries of art and science, delving into realms of engineering and invention with an insatiable curiosity. Around 1490, amidst his prolific output, he conceived a truly unique musical instrument: the viola organista. This design was more than a mere sketch; it was a theoretical masterpiece, combining the expressive qualities of a violin with the mechanical precision of a keyboard instrument.

Da Vinci’s concept fused the stringed essence of a violin with the mechanism of a piano, allowing it to be played via a keyboard rather than a bow. This groundbreaking idea aimed to produce sustained string tones akin to bowed instruments, but with the polyphonic capabilities and ease of a keyboard. However, as was often the case with many of his visionary designs, Leonardo’s boundless curiosity led him to other projects before he could bring the viola organista into physical existence. It remained a set of intricate drawings, a silent testament to his musical imagination.

Centuries passed before inventors rediscovered these captivating drawings, which, despite their incompleteness, held enough inspiration to spark new creations. One notable successor was the German musician Hans Haiden, who, in 1575, built the Geigenwerk, an instrument similar in concept to Leonardo’s vision. This demonstrates the enduring power of a foundational idea, capable of influencing future innovators even when left unfinished by its originator.

The most faithful realization of Leonardo’s original design would not arrive until much later. In 2013, Polish organ builder Slawomir Zubrzycki undertook the monumental task of constructing a playable viola organista, meticulously basing his work on the centuries-old sketches. Nearly 500 years after Leonardo’s death, his musical dream finally took tangible form, producing sounds described as “hauntingly beautiful.” It stands as a profound example of how a genius’s foresight can transcend epochs, eventually finding its voice in a world ready to receive it.

7. **Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine**The early 19th century presented a significant challenge in the world of mathematics: the laborious and error-prone process of calculating extensive tables by hand. It was against this backdrop that the visionary mathematician Charles Babbage conceived a revolutionary solution, dreaming of an automatic, flawlessly accurate mechanical calculator. He christened this ambitious endeavor the Difference Engine, setting the stage for what would become a foundational concept in the history of computing.

Babbage’s design was a marvel of mechanical ingenuity, far removed from the electronic computers of today. Instead of circuits and currents, his machine was to be powered by an intricate network of “interlocking toothed wheels,” each representing digits from 0 to 9. These gears were engineered to perform complex calculations, carrying over numbers and even printing the final results onto soft metal. It was an astonishingly forward-thinking concept, embodying principles that would much later underpin modern digital computation, showcasing a profound grasp of automation.

Bolstered by the British government’s financial backing, Babbage commenced work in 1823, collaborating with the skilled engineer Joseph Clement. However, the project was destined to face a barrage of difficulties. Intricate engineering hurdles combined with persistent funding disputes ultimately led Clement to withdraw his participation. Consequently, the crucial government support, which had already amounted to over £17,000, eventually dissipated, leaving Babbage’s grand vision in limbo. Heartbroken, he passed away in 1871, convinced that his magnificent machine would forever remain unrealized.

Yet, the narrative of the Difference Engine did not conclude with Babbage’s death. His meticulous designs and groundbreaking principles were too potent to be forgotten. In a remarkable tribute to his genius, London’s Science Museum embarked on a project in 1991 to construct a fully working Difference Engine. Crucially, they utilized only the technologies and materials that would have been available during Babbage’s own era. The result was breathtaking: a monumental machine comprising 4,000 precisely crafted parts and weighing over three tons, which operated flawlessly, exactly as Babbage had intended. This posthumous vindication underscored the sheer brilliance of his original design, proving that his vision was not merely fanciful but entirely feasible, redefining the very concept of mechanical computation.

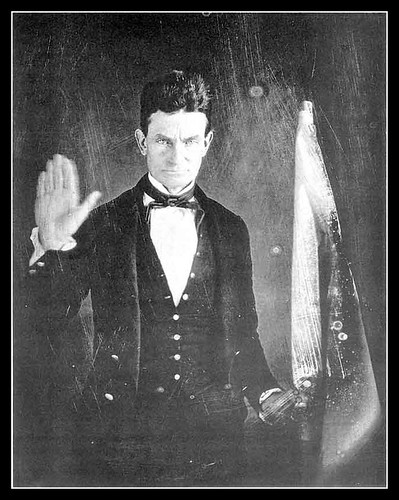

8. **John Browning’s High-Power Pistol**In the early 1920s, the French military articulated a pressing need for a new sidearm: a compact handgun capable of holding a minimum of ten rounds, designed for easy field disassembly, and crucially, affordable to mass-produce. This challenging specification attracted the attention of one of history’s most renowned firearm designers, John Browning. In 1923, he submitted a patent for a pistol featuring several groundbreaking innovations for its time, including a thumb safety and an external hammer, elements that would become standard in future handgun designs.

Tragically, Browning’s immense contributions to firearm technology were cut short. He died of heart failure in 1926, before he could bring his advanced pistol design to full fruition. However, his seminal work did not die with him. His dedicated colleague, Dieudonné Saive, took up the mantle, meticulously refining Browning’s initial concepts. This continuation of effort, building upon a visionary foundation, proved critical in translating a brilliant idea into a functional, market-ready product.

By 1935, Saive’s refinements culminated in the debut of the finished weapon, aptly named the Browning Hi-Power. Although the French military ultimately chose not to adopt it, the pistol rapidly achieved global success, earning widespread acclaim for its potent combination of power, reliability, and innovative design. Its influence quickly spread far beyond national borders, becoming a benchmark for handgun development worldwide.

The Hi-Power’s impact was profound and enduring. It saw extensive use across countless 20th-century conflicts, establishing itself as one of history’s most iconic and recognizable handguns. Remarkably, its design remains so robust and effective that it is still produced by several manufacturers today, almost a century after Browning first conceived its fundamental principles. This sustained legacy is a powerful testament to John Browning’s unparalleled genius and foresight in an industry where innovation is constantly driven by performance and reliability.

9. **Enrico Forlanini’s Omnia Dir Blimp**In the wake of World War I, the burgeoning field of aviation was ripe with ambitious dreams for safer, more maneuverable airships. Italian inventor Enrico Forlanini emerged as a leading pioneer in this quest, designing one of the era’s most advanced lighter-than-air craft: the Omnia Dir, an abbreviation for Omnia Dirigibile. Introduced in 1930, this impressive blimp measured a substantial 56 meters (184 feet) in length and boasted a considerable capacity of 4,000 cubic meters of gas, marking it as a significant contender in airship development.

The true genius of Forlanini’s Omnia Dir lay in its innovative propulsion system. Unlike conventional propeller-driven designs, this airship utilized “compressed-air jets” positioned at both its front and back. This novel system provided an unprecedented degree of control and thrust for its time, promising enhanced maneuverability and operational efficiency. Sadly, Forlanini passed away later in that very same year, 1930, and with his demise, the vital momentum behind the project began to dissipate.

Despite its promising design and initial test flights, the Omnia Dir never advanced to mass production. It became another compelling “what if” in aviation history, a testament to brilliant engineering that could not overcome the loss of its visionary creator. Nevertheless, Forlanini’s groundbreaking work, particularly his exploration of auxiliary-thrust systems, had a lasting influence. His concepts contributed significantly to the evolution of modern aircraft design, inspiring advancements that subsequently improved both the speed and maneuverability of future aerial vehicles. Though the Omnia Dir itself never took off commercially, its conceptual impact on aviation endures, proving that even unrealized projects can sow the seeds of future success.

10. **Bill Lear’s Lear Fan 2100**In the late 1970s, Bill Lear, the celebrated aviation innovator and founder of Lear Jet Corporation, envisioned a radically new kind of airplane. His concept, the Lear Fan 2100, was designed to leverage the revolutionary properties of “carbon-graphite composite,” a material renowned for its exceptional strength-to-weight ratio. This innovative choice of material was intended to make the aircraft substantially lighter than traditional aluminum designs, promising a new era of efficiency in personal and business aviation.

The Lear Fan 2100’s unique propulsion system was equally ingenious. It was conceived with “two turboprop engines driving a single rear-mounted propeller,” an arrangement intended to allow the aircraft to achieve speeds comparable to jets while weighing roughly half as much as its aluminum counterparts. When Lear presented this ambitious concept to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), officials raised legitimate concerns regarding the gearbox and the overall aerodynamics of such a novel design. Unfortunately, before these engineering challenges could be fully addressed and the design proven, Lear succumbed to leukemia in 1978, leaving his groundbreaking project unfinished.

Undeterred by her husband’s passing, Moya Lear, driven by an unwavering determination to see his dream realized, stepped forward to champion the project. She successfully secured vital support from the British government, enabling the completion of the prototype aircraft. The Lear Fan’s maiden flight in 1981 was a profound triumph, not just of engineering, but of persistence in the face of adversity, a testament to the enduring power of a visionary idea.

While the Lear Fan 2100 ultimately never entered mass production, its existence served as a powerful proof of concept for composite aircraft design and integrated propulsion systems. Today, three of these pioneering planes still exist, proudly displayed at significant aviation institutions: the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington; the Frontiers of Flight Museum in Dallas, Texas; and the FAA facility in Oklahoma City. Each aircraft stands as a poignant tribute to Bill Lear’s extraordinary inventive spirit and the visionary dream he cultivated, even though he never lived to witness his revolutionary aircraft truly take flight into widespread commercial success. His legacy, however, continues to inspire.

These ten extraordinary narratives underscore a profound truth about innovation: genius often operates on a timeline far grander than a single human life. From the intricate gears of a mechanical calculator conceived in the 19th century to the composite airframe of a futuristic plane born in the late 20th, these pioneers laid intellectual groundwork that reshaped industries and everyday existence. Their stories remind us that true visionaries don’t just invent; they ignite sparks that, even if unseen in their own time, eventually flare into the technologies that define our future. Their posthumous successes are not merely footnotes in history but vibrant chapters demonstrating the enduring power of an idea whose time, eventually, always comes.