The human mind is an intricate labyrinth, a universe of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that has fascinated thinkers for millennia. Our innate curiosity about “why we do what we do,” “how we think,” and “what drives our feelings” has spurred an enduring quest for understanding. This profound inquiry forms the bedrock of psychology, a scientific discipline dedicated to unraveling the mysteries of consciousness, the nuances of behavior, and the myriad mental processes that define our existence.

Psychology, in its expansive scope, seamlessly bridges the natural and social sciences, offering a unique lens to examine both the biological underpinnings of our brains and the intricate dynamics of individual and group interactions. From the subtle shifts in our attention to the profound depths of our motivations, this field provides a framework for comprehending the rich tapestry of human experience. It’s a journey not just into the abstract, but into the practical realities that shape our daily lives and our collective societal interactions.

To truly appreciate the insights psychology offers, from complex decision-making to simplest preferences, it’s essential to first grasp its foundational principles and historical trajectory. This article explores psychology’s origins, its evolution from philosophical discourse to rigorous empirical science, and the groundbreaking minds who charted its course. Understanding this history illuminates psychology’s capacity to reveal the core drivers of human behavior.

1. **Defining Psychology: Its Scientific Scope and Subject Matter**

At its heart, psychology is fundamentally “the scientific study of behavior and mind.” This definition encompasses an immense scope, covering observable actions and intricate internal conscious and unconscious processes in humans and nonhumans. As an academic discipline, it uniquely “crossing the boundaries between the natural and social sciences,” integrating biological insights with the dynamics of individuals and groups.

The subject matter is wonderfully diverse, including “the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both conscious and unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feelings, and motives.” Psychologists “understand the role of mental functions in individual and social behavior” or “explore the physiological and neurobiological processes that underlie cognitive functions and behaviors,” highlighting the field’s comprehensive nature.

Psychologists research specialized areas like “perception, cognition, attention, emotion, intelligence, subjective experiences, motivation, brain functioning, and personality.” Their interests also extend to “interpersonal relationships, psychological resilience, family resilience, and other areas within social psychology,” including “the unconscious mind.” While applied to mental health, psychology’s broader aim is “to benefit society” through deeper understanding of human activity.

Read more about: Unlocking Influence: How a Deep Understanding of Psychology’s Foundations Can Empower Your Salary Negotiations

2. **The Etymological Roots and Evolving Definitions of Psychology**

The word “psychology” illuminates its foundational concerns, tracing to ancient Greek “psyche” for “spirit or soul,” and “-λογία -logia,” meaning “study or research.” This etymology reveals a long-standing fascination with the internal world. The formal term emerged in the Renaissance, with Marko Marulić’s “psychiologia” (1510–1520), and first appeared in English in Steven Blankaart’s “The Physical Dictionary” (1694), defining it as treating “of the Soul.”

This early distinction between body and soul highlighted a key conceptual division. The Greek letter Ψ (psi), the first letter of “psyche,” became the widely recognized symbol for the field, signifying its deep historical roots and focus on the inner life.

Definitions evolved significantly. William James’s 1890 definition: “the science of mental life, both of its phenomena and their conditions,” emphasized subjective experience. However, John B. Watson “contested” this in 1913, advocating a “purely objective experimental branch of natural science” focused on “the prediction and control of behavior.” This shifted the field towards rigorous scientific experimentation and measurable actions.

Read more about: Mastering the Mechanics of Belief: 14 Enduring Models of ‘Cults’ Worth Understanding for Tomorrow’s World

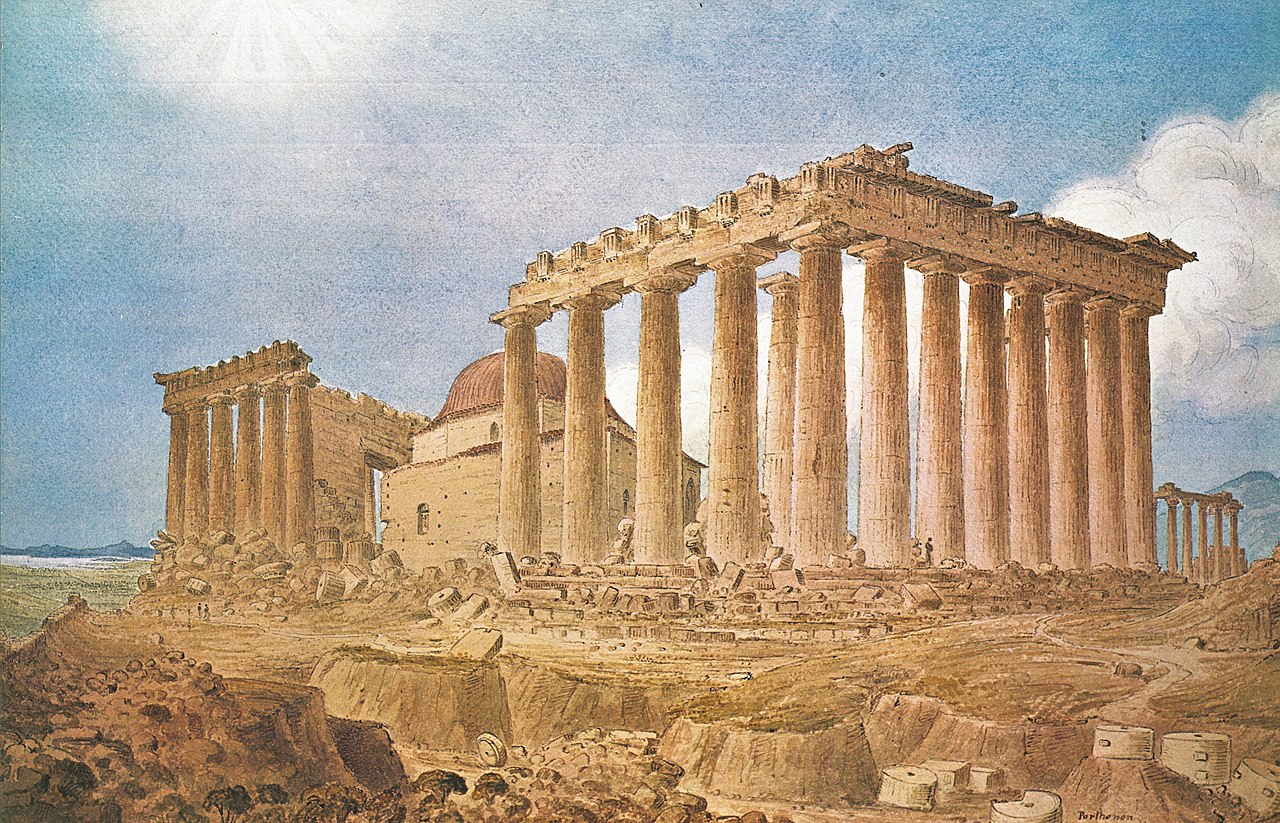

3. **Ancient Philosophical Foundations: Psychology Across Civilizations**

Long before psychology became a distinct science, ancient civilizations like Egypt, Greece, China, India, and Persia profoundly engaged with questions of mind and behavior. Their philosophical inquiries laid crucial groundwork by articulating initial theories about consciousness, emotion, and human nature, reflecting a universal drive to understand the inner self.

In Ancient Egypt, the “Ebers Papyrus” mentioned “depression and thought disorders.” Greek philosophers such as “Thales, Plato, and Aristotle” “addressed the workings of the mind.” Hippocrates, in the 4th century BC, theorized that “mental disorders had physical rather than supernatural causes.” Plato suggested the brain as the seat of mental processes (387 BCE), while Aristotle proposed the heart (335 BCE).

Further east, Chinese philosophy, influenced by “Laozi and Confucius, as well as the teachings of Buddhism,” drew insights from “introspection, observation, and techniques for focused thinking and behavior.” “The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine” identified “the brain as the nexus of wisdom and sensation.” Indian philosophy, influenced by Hinduism, explored “distinctions in types of awareness,” with Vedic texts highlighting the separation between the “transient mundane self and their eternal, unchanging soul.”

4. **Enlightenment Thinkers and the Emergence of Psychology as a Science**

The Enlightenment in Europe marked a pivotal period where philosophical inquiry began laying more specific foundations for psychology. Driven by reason and systematic observation, thinkers started conceptualizing the mind in ways that moved it closer to scientific investigation.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) applied calculus principles to the mind, arguing that “mental activity took place on an indivisible continuum” and that conscious and unconscious awareness differed only “as a matter of degree.” Christian Wolff formally recognized psychology as its own science, publishing “Psychologia Empirica” (1732) and “Psychologia Rationalis” (1734), carving out a distinct academic space.

Despite this, Immanuel Kant “explicitly rejected the idea of an experimental psychology,” arguing that “the manifold of inner observation can be separated only by mere division in thought.” Yet, Ferdinand Ueberwasser designated himself “Professor of Empirical Psychology and Logic” in 1783, and the Prussian state made psychology a mandatory discipline in 1825, signaling its growing academic importance.

Read more about: Unlocking Influence: How a Deep Understanding of Psychology’s Foundations Can Empower Your Salary Negotiations

5. **The Birth of Experimental Psychology: Paving the Way for Empirical Study**

The mid-19th century witnessed a transformative shift: the birth of experimental psychology. This crucial period saw a growing belief that the human mind could be subjected to rigorous scientific investigation, marking a profound departure from philosophical speculation towards empirical observation and measurement, fundamentally changing psychology’s trajectory.

Philosopher John Stuart Mill believed “the human mind was open to scientific investigation,” proposing a “mental chemistry” for complex ideas. Gustav Fechner in Leipzig pioneered “psychophysics research in the 1830s,” articulating the Weber–Fechner law, demonstrating “human perception of a stimulus varies logarithmically according to its intensity.” His “Elements of Psychophysics” (1860) proved “mental processes could not only be given numerical magnitudes, but also that these could be measured by experimental methods.”

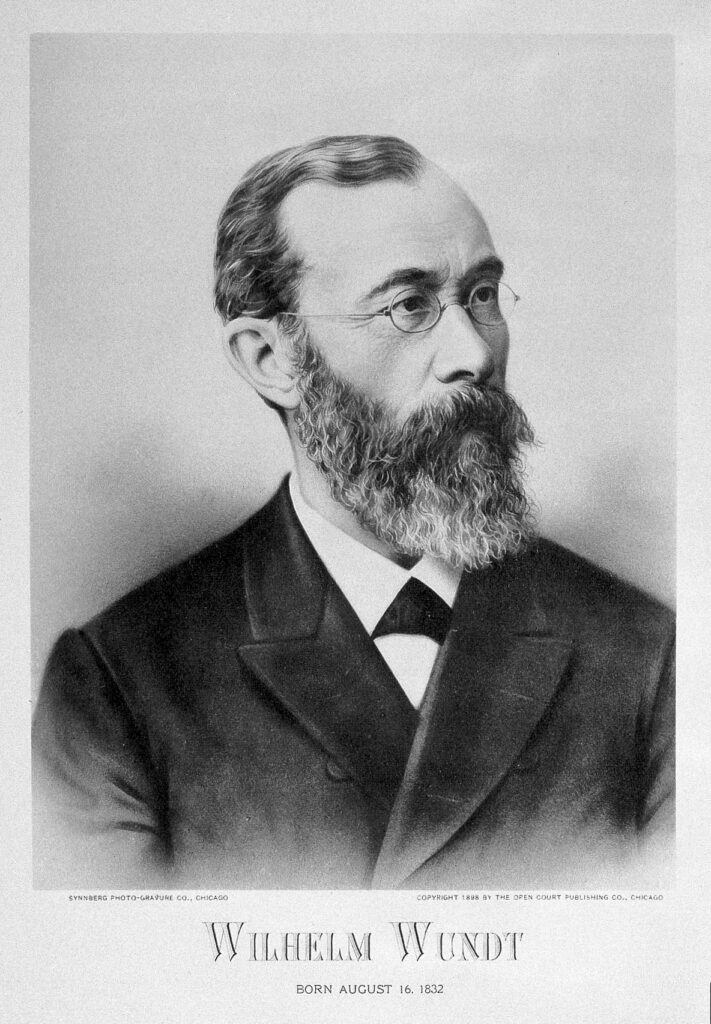

This path led to formal psychological laboratories. Hermann von Helmholtz trained Wilhelm Wundt, who, at Leipzig University, “established the psychological laboratory that brought experimental psychology to the world.” Wundt focused on “breaking down mental processes into the most basic components,” inspired by “advances in chemistry.” This systematic, analytical approach became a hallmark, with Paul Flechsig and Emil Kraepelin also establishing influential labs focused on experimental psychiatry.

Read more about: Unlocking Influence: How a Deep Understanding of Psychology’s Foundations Can Empower Your Salary Negotiations

6. **Pioneering Figures and the Establishment of Early Laboratories**

Following Wilhelm Wundt’s foundational work, psychological laboratories rapidly proliferated across Europe and the United States, marking the institutionalization of experimental psychology. These labs became crucial hubs for research, training, and knowledge dissemination, attracting brilliant minds and cementing psychology’s legitimacy.

G. Stanley Hall, an American student of Wundt, established an internationally influential psychology laboratory at Johns Hopkins University. He trained Yujiro Motora, who then “brought experimental psychology, emphasizing psychophysics, to the Imperial University of Tokyo.” Similarly, Wundt’s assistant, Hugo Münsterberg, taught at Harvard, influencing Narendra Nath Sen Gupta, who founded a psychology department and laboratory at the University of Calcutta in 1905.

Wundt’s students applied psychological principles to practical domains. Walter Dill Scott, Lightner Witmer, and James McKeen Cattell dedicated efforts to “developing tests of mental ability.” Cattell became “the first professor of psychology in the United States” and co-founder of “Psychological Review,” later founding the Psychological Corporation. Witmer specialized in “the mental testing of children,” while Scott focused on “employee selection,” showcasing the early diversification into applied psychology.

Read more about: Antarctica’s Icy Archives: Unearthing Mysterious Human Remains and Historic Discoveries That Still Challenge Our Understanding

7. **Divergent Schools of Thought: Structuralism, Functionalism, and Gestalt Psychology**

As experimental psychology gained traction, different theoretical frameworks, or “schools of thought,” emerged, each offering a distinct approach to understanding the mind. These early schools represent psychology’s dynamic effort to define its subject matter and methodology, sparking vibrant intellectual debates that profoundly shaped the discipline’s future trajectory.

One influential school was “structuralist” psychology, advanced by Wundt’s student Edward Titchener at Cornell University. Structuralism aimed to “analyze and classify different aspects of the mind, primarily through the method of introspection.” Its goal was to break down conscious experience into fundamental sensations, feelings, and images, identifying the mind’s basic structure. This atomistic approach, while systematic, faced critiques for its reliance on subjective introspection.

In contrast, “functionalism” emerged as a prominent American school, championed by William James, John Dewey, and Harvey Carr. Functionalism represented “an expansive approach to psychology that underlined the Darwinian idea of a behavior’s usefulness to the individual.” Rather than dissecting the mind’s static structure, functionalists focused on the *purpose* or *function* of mental processes in adapting to the environment. James’s “The Principles of Psychology” (1890) famously described the “stream of consciousness,” while Dewey integrated psychology with societal concerns.

Another significant school was “Gestalt psychology,” co-founded by Wolfgang Kohler, Max Wertheimer, and Kurt Koffka. This approach was revolutionary in asserting “that individuals experience things as unified wholes,” rather than as sums of their parts. Gestaltists maintained that “the whole of experience is important, ‘and is something else than the sum of its parts, because summing is a meaningless procedure, whereas the whole-part relationship is meaningful.'” This holistic perspective emphasized that perception is organized and meaningful, with context playing a crucial role.