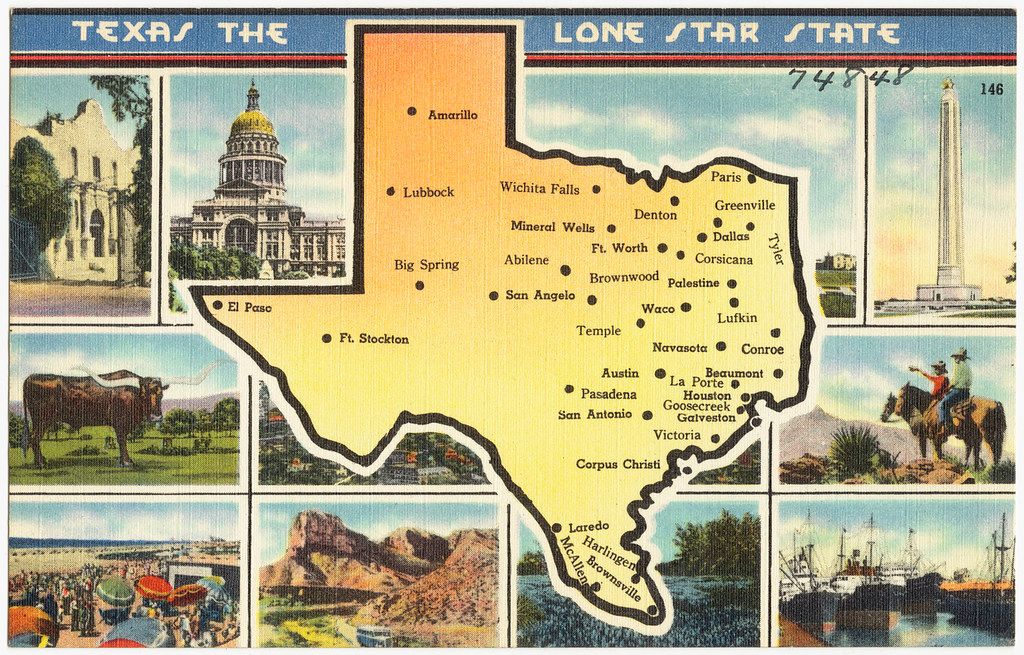

Texas, affectionately known as the Lone Star State for its former status as an independent country, the Republic of Texas, stands as a formidable entity within the United States. As the most populous state in the South Central region and the second-largest by both area and population, encompassing 268,596 square miles (695,660 km2) and home to over 31 million residents as of 2024, Texas presents a tapestry woven with deep historical roots, profound cultural influences, and remarkable economic dynamism. Its distinctive identity, shaped by centuries of geopolitical shifts and the resilience of its diverse inhabitants, continues to define its prominence on the national and international stage.

From the outset, Texas’s unique position was clear, bordered by Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, and New Mexico to the west, while sharing an international border with the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas to the south and southwest, and boasting a coastline on the Gulf of Mexico. This geographical confluence has intrinsically linked its destiny with a complex interplay of European powers and indigenous civilizations, setting the stage for a dramatic historical narrative.

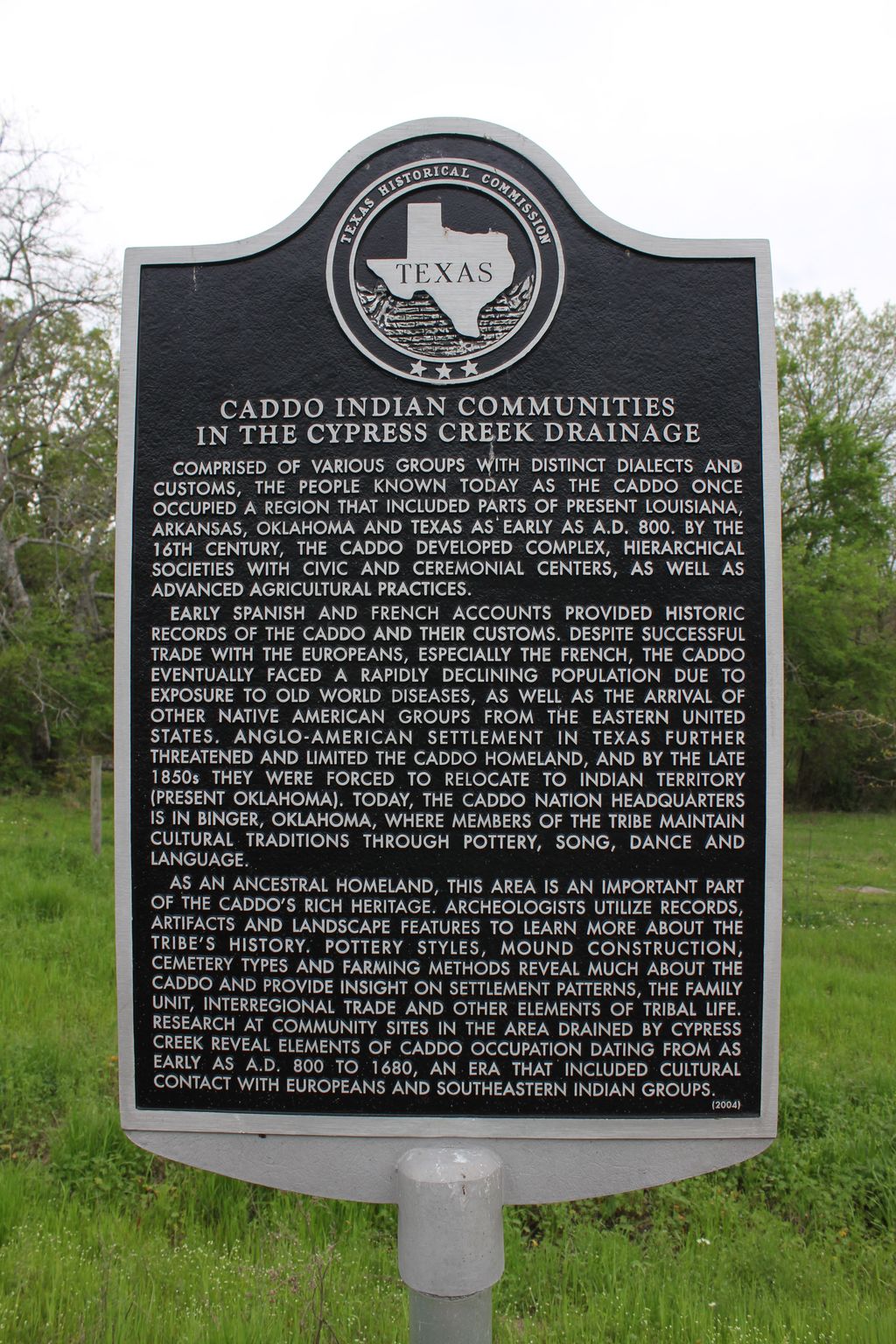

The earliest historical records reveal a land deeply inhabited by indigenous cultures long before European contact. Archaeologists have identified three major Indigenous cultures that reached their developmental peak in this territory: the Ancestral Puebloans from the upper Rio Grande region, the Mississippian culture (also known as Mound Builders) along the Mississippi River Valley, and the civilizations of Mesoamerica. These vibrant societies laid the foundation for the diverse linguistic and cultural landscape encountered by early explorers.

When Europeans arrived, the state was home to Caddoan, Atakapan, Athabaskan, Coahuiltecan, and Uto-Aztecan languages, alongside several language isolates like Tonkawa. Tribes such as the Uto-Aztecan Puebloan and Jumano peoples lived near the Rio Grande, while Athabaskan-speaking Apache tribes roamed the interior. The agricultural, mound-building Caddo controlled much of the northeastern part of the state, along the Red, Sabine, and Neches River basins, and Atakapan peoples like the Akokisa and Bidai, along with the Karankawa, populated the Gulf Coast.

Spain was the first European power to claim and control Texas, a legacy that began in 1519 with Alonso Álvarez de Pineda’s map of the Gulf Coast. Nine years later, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his cohort became the first Europeans in what is now Texas, reporting in 1528 that “half the natives died from a disease of the bowels and blamed us.” His observations provided early insights into the life of the Ignaces Natives of Texas.

Despite early explorations by figures like Francisco Vázquez de Coronado in 1541 and Hernando de Soto’s expedition from the east, European powers largely ignored the area until 1685. A crucial miscalculation by René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle led to the accidental establishment of Fort Saint Louis at Matagorda Bay instead of along the Mississippi River. This French colony, unfortunately, lasted only four years, succumbing to harsh conditions and hostile natives.

Spanish authorities, concerned by the French presence, responded by constructing several missions among the Caddo in East Texas in 1690. Though Caddo resistance initially led Spanish missionaries to return to Mexico, France’s subsequent settlement of Louisiana prompted Spain to establish a new series of missions in East Texas in 1716, culminating in the creation of San Antonio as the first Spanish civilian settlement two years later. This marked a significant step in the European establishment within the region.

Under Spanish colonial rule in the 18th century, the area was known as Nuevas Filipinas or Nuevo Reino de Filipinas, and later provincia de los Tejas or provincia de Texas. Hostile native tribes and the considerable distance from other Spanish colonies deterred significant settlement, making it one of New Spain’s least populated provinces. The Spanish peace treaty with the Lipan Apache in 1749, however, inadvertently angered other tribes like the Comanche, Tonkawa, and Hasinai, leading to new conflicts and alliances.

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase by the United States ignited further territorial disputes, with American authorities insisting the agreement also included Texas. The boundary was eventually set at the Sabine River in 1819, the modern border with Louisiana. However, many U.S. settlers, eager for new land, refused to recognize this agreement, leading to filibustering expeditions and continued migration into the contested area.

Texas became part of Mexico following the Mexican War of Independence in 1821, and due to its low population, its core territory was assigned to the state of Coahuila y Tejas. Hoping to mitigate constant Comanche raids, Mexican Texas liberalized its immigration policies, attracting settlers from outside Mexico and Spain, primarily the U.S. Stephen F. Austin was the first American empresario granted permission to operate a colony, leading to the settlement of the Old Three Hundred along the Brazos River in 1822.

The population of Texas experienced rapid growth, from about 3,500 people in 1825 (mostly of Mexican descent) to approximately 37,800 by 1834, with only 7,800 being of Mexican descent. This influx, coupled with immigrants openly flouting Mexican law, particularly the prohibition against slavery, prompted Mexican authorities in 1830 to prohibit further immigration from the United States. Yet, illegal immigration persisted, exacerbating tensions that eventually escalated into open revolt.

The Anahuac Disturbances in 1832 marked the first open uprising against Mexican rule, coinciding with a wider revolt in Mexico. Texians sided with the federalists, driving Mexican soldiers out of East Texas and capitalizing on the lack of oversight to agitate for greater political freedom. This led to the Conventions of 1832 and 1833, where Texians discussed and reiterated their demands for independent statehood and other issues.

The Texas Revolution erupted in late 1835 with the Battle of Gonzales, as tensions between federalists and centralists within Mexico continued to simmer. The provisional government formed by Texian delegates soon collapsed from infighting, leaving Texas without clear governance for the first two months of 1836. Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna personally led an army to quell the revolt, achieving significant victories like the defeat of Texian resistance along the coast, culminating in the Goliad massacre, and the overwhelming of Texian defenders after a thirteen-day siege at the Battle of the Alamo.

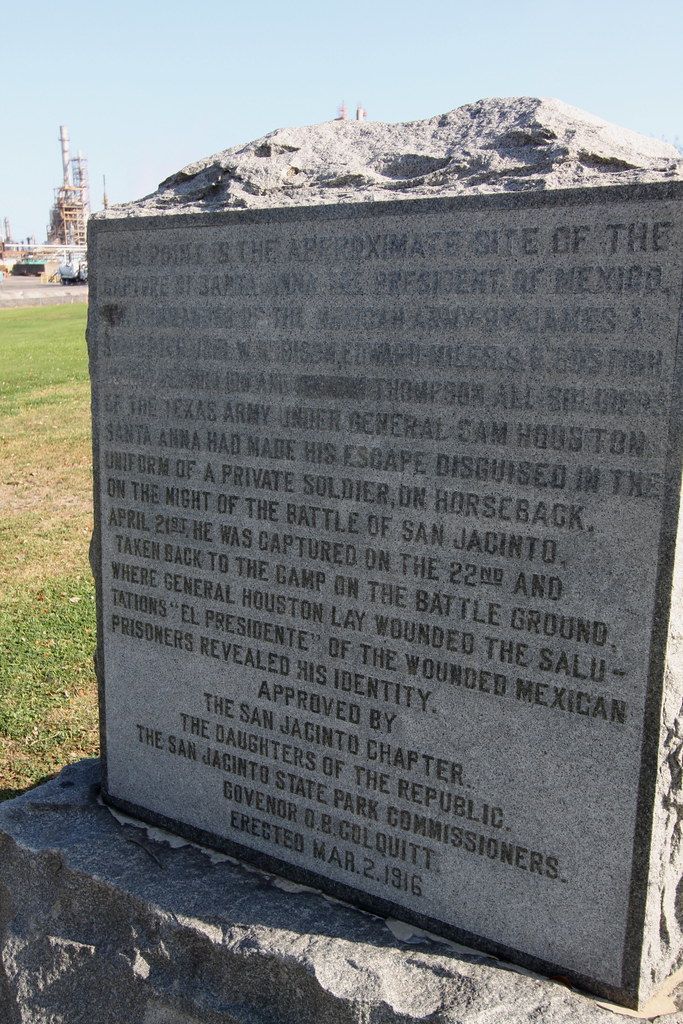

Despite these defeats, the newly elected Texian delegates to the Convention of 1836 swiftly signed a declaration of independence on March 2, forming the Republic of Texas. The new government, alongside settlers, joined the Runaway Scrape, fleeing the advancing Mexican army. However, the tide turned dramatically at the Battle of San Jacinto, where the Texian Army, commanded by Sam Houston, attacked and decisively defeated López de Santa Anna’s forces.

López de Santa Anna’s capture forced him to sign the Treaties of Velasco, effectively ending the war and securing Texas’s independence. The Constitution of the Republic of Texas, however, reflected the contentious issue of the time, prohibiting the government from restricting or freeing slaves and requiring free people of African descent to leave the country. The young republic then faced internal political battles, with Mirabeau B. Lamar leading a nationalist faction advocating continued independence and expansion to the Pacific, while Sam Houston championed annexation to the United States and peaceful coexistence with Native Americans, illustrating the fledgling nation’s complex aspirations.

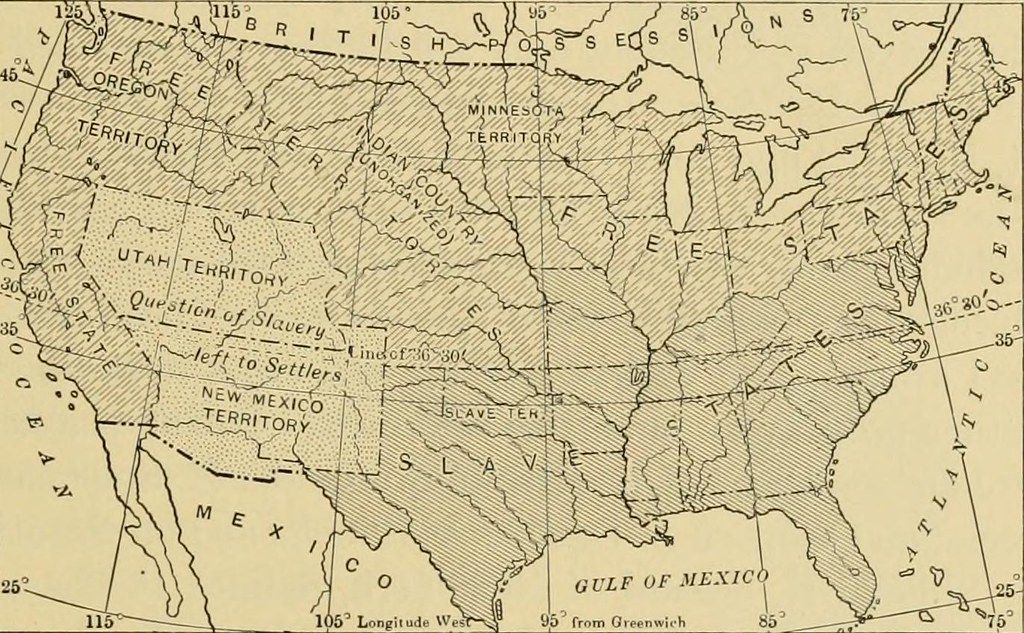

Texas first applied for annexation to the United States in 1836, but its status as a slaveholding country made its admission controversial and it was initially rebuffed. This status, combined with Mexican diplomacy, complicated Texas’s foreign alliances and trade relationships. The Comanche Indians posed significant opposition to the Republic, engaging in multiple raids on settlements, and Mexico launched two small expeditions into Texas in 1842, briefly capturing San Antonio twice, yet not maintaining an occupying force.

Statehood was finally achieved on December 29, 1845, when James K. Polk’s expansionist platform led to Texas’s admission as the 28th U.S. state. Mexico immediately broke diplomatic relations, as the United States claimed Texas’s border stretched to the Rio Grande, while Mexico maintained it was the Nueces River. President Polk’s order for General Zachary Taylor to move south to the Rio Grande on January 13, 1846, precipitated the Thornton Affair, igniting the Mexican–American War, with early battles fought on Texan soil including the Siege of Fort Texas, Battle of Palo Alto, and Battle of Resaca de la Palma.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the two-year conflict in 1848, with Mexico ceding undisputed control of Texas to the U.S. and establishing Texas’s borders at the Rio Grande in return for US$18,250,000 (equivalent to $663,247,000 in 2024). The Compromise of 1850 further defined Texas’s present boundaries, with the state ceding claims to land that would become parts of New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Wyoming, in exchange for the federal government assuming $10 million of the old republic’s debt.

Post-war Texas experienced rapid growth as migrants, including enslaved African Americans, poured into its cotton lands; the number of enslaved people tripled from 58,000 to 182,566 between 1850 and 1860. This economic structure profoundly shaped the state’s stance leading up to the Civil War, where Black people comprised 30 percent of the state’s population and were overwhelmingly enslaved.

Texas re-entered war following the election of 1860, with a state convention in Austin adopting an Ordinance of Secession by a vote of 166–8 on February 1, 1861, approved by voters on February 23. Texas formally joined the Confederate States of America on March 4, 1861. Not all Texans initially favored secession, notably Governor Sam Houston, who was deposed after refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy, despite President Lincoln’s offers of Union troops to keep him in office.

Though far from the major battlefields, Texas contributed significantly to the Confederate cause, acting as the “backdoor of the Confederacy” due to trade with Mexico that bypassed the Union blockade. Confederate forces successfully repelled Union attempts to close this route, but the state’s role as a supply hub diminished after the Union captured the Mississippi River in mid-1863. The final battle of the Civil War, a Confederate victory, was fought at Palmito Ranch, near Brownsville, Texas.

Following the Civil War and the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, Texas descended into anarchy for two months before Union General Gordon Granger assumed authority. Juneteenth, celebrated annually, commemorates Granger’s announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in Galveston, nearly two and a half years after its original issuance. Despite social volatility, agricultural depression, and labor issues marking the early years of Reconstruction, Texas’s civilian government was declared restored in 1866, and Congress resumed allowing elected representatives into the federal government by 1870.

Unlike many parts of the Deep South, Texas’s economy, less dependent on slaves, recovered more quickly from the devastation of the war. The late 19th century saw Texas as a frontier territory, notorious as a haven for those escaping debt or other problems, leading to the common expression “Gone to Texas.” However, it also attracted legitimate businessmen and settlers, fostering a renewed economic vibrancy. The cattle industry thrived, though its profitability eventually waned, while cotton and lumber grew into major industries, accompanied by a rapid expansion of railroad networks and the port at Galveston.

In 1900, Texas tragically suffered the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history during the Galveston hurricane. Just a year later, on January 10, 1901, the discovery of Spindletop, the first major oil well in Texas located south of Beaumont, initiated an unprecedented economic boom that transformed the state for much of the 20th century. Oil production reached an average of three million barrels per day at its peak in 1972, solidifying Texas’s identity as an energy powerhouse.

Amidst economic changes, the early 20th century also brought significant political shifts. In 1901, the Democratic-dominated state legislature passed a poll tax and established white primaries, effectively disenfranchising most Black, poor White, and Latino voters, consolidating Democratic power. The Socialist Party briefly emerged as the second-largest party after 1912, coinciding with a national socialist upsurge, but its popularity waned following vilification for opposition to U.S. involvement in World War I.

The Great Depression and the Dust Bowl dealt a severe blow to the state’s economy, leading to a significant out-migration, particularly of Black people, who left Texas during the Great Migration to seek work in the Northern United States or California and escape segregation. By 1940, Texas’s population was 74% White, 14.4% Black, and 11.5% Hispanic. World War II, however, spurred a dramatic transformation, with federal money pouring in to build military bases, munitions factories, and hospitals, and 750,000 Texans serving in the military, fueling explosive growth in cities and new industries.

The mid-20th century marked Texas’s pivotal transformation from a predominantly rural and agricultural state to an urbanized and industrialized one. As part of the Sun Belt, Texas experienced robust economic growth, particularly from the 1970s through the early 1980s, driven by diversification that lessened its reliance on the petroleum industry. This period also saw significant population growth due to large levels of in-migration, with Hispanics and Latino Americans surpassing Blacks as the largest minority group by 1990.

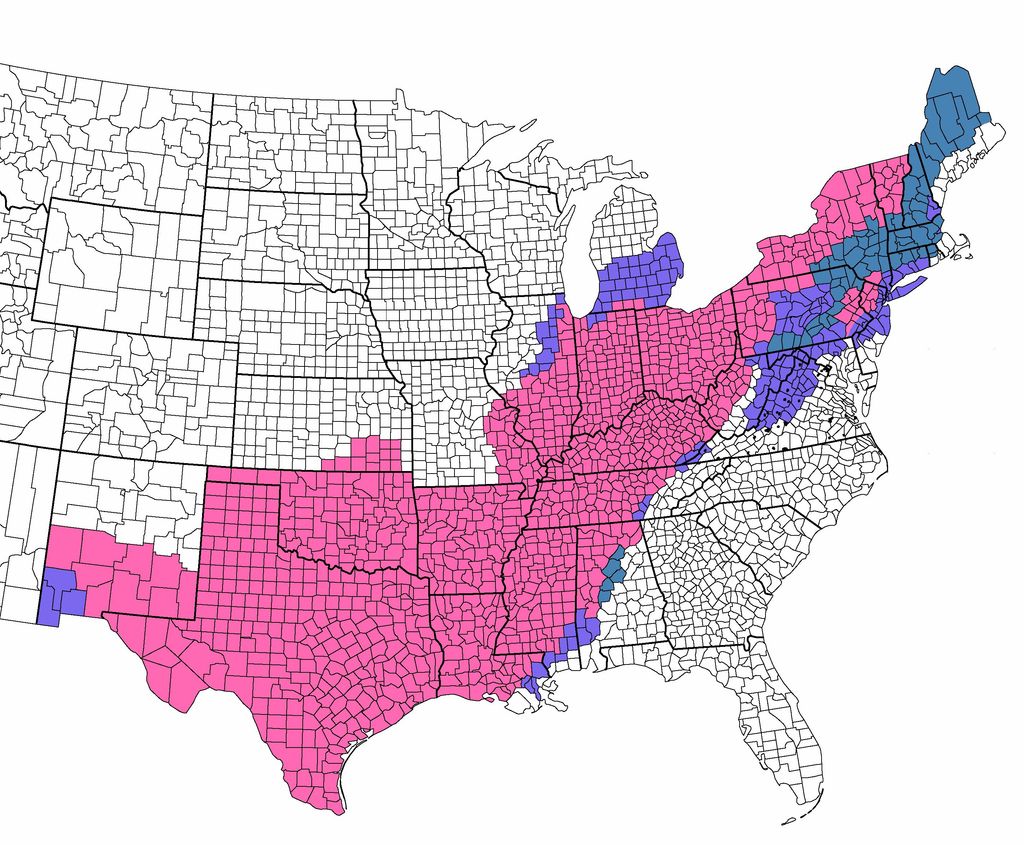

In the late 20th century, the Republican Party replaced the Democratic Party as the dominant political force in the state. However, beginning in the early 21st century, metropolitan areas like Dallas–Fort Worth and Greater Austin emerged as centers for the Texas Democratic Party in statewide and national elections, reflecting a growing acceptance of liberal policies in urban areas. This dynamic underscores the evolving political landscape within the state.

Texas has become a major destination for migration, notably gaining an influx of business relocations and regional headquarters from California companies from the mid-2000s to 2019. It was named the most popular state to move for three consecutive years, with one 2019 study reporting a growth rate of 1,000 people per day, testament to its economic opportunities and appeal.

The state has also navigated significant challenges in recent years. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Texas saw its first confirmed case on March 4, 2020. Governor Greg Abbott initiated phase one of re-opening the economy on April 27, 2020, and famously refused further lockdowns despite a rise in cases in autumn 2020. Texas was also selected in November 2020 as one of four states to test Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine distribution, demonstrating its critical role in national health efforts.

In February 2021, Winter Storm Uri delivered a major weather emergency, causing historically high power usage that overwhelmed the state’s power grid. ERCOT, the main operator of the Texas Interconnection grid, declared an emergency and implemented rolling blackouts, resulting in over 3 million Texans without power and over 4 million under boil-water notices, highlighting the vulnerabilities of critical infrastructure during extreme weather events.

Geographically, Texas is a land of immense diversity. As the second-largest U.S. state by area and the largest within the contiguous United States, if it were an independent country, Texas would rank as the 39th-largest globally. Its intricate regional classification arises from 10 climatic regions, 14 soil regions, and 11 distinct ecological regions, encompassing differences in soils, topography, geology, rainfall, and plant and animal communities.

From east to west, the terrain transitions dramatically: from the thick piney woods of the Gulf Coastal Plains, wrapping around the Gulf of Mexico, to the gently rolling, forested Interior Lowlands, which include the Cross Timbers and Caprock Escarpment. Central Texas and its panhandle are dominated by the prairie and steppe of the Great Plains region, extending through the Llano Estacado to the hill country near Lago Vista and Austin. Far West Texas, or the “Trans-Pecos,” constitutes the Basin and Range Province, presenting the most varied landscapes with sand hills, the Stockton Plateau, desert valleys, wooded mountain slopes, and desert grasslands.

Texas is crisscrossed by 3,700 named streams and 15 major rivers, with the Rio Grande being the largest, alongside others like the Pecos, Brazos, Colorado, and Red River. While natural lakes are few, Texans have constructed over a hundred artificial reservoirs, a testament to human ingenuity in adapting to the natural environment. The state’s unique geological position, as the southernmost part of the Great Plains, transitions into the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico, with a stable Mesoproterozoic craton giving way to the oceanic crust of the Gulf of Mexico.

Ancient rocks dating back 1,600 million years form part of Texas’s geological foundation. The collision of Laurasia and Gondwana to form Pangea in the Pennsylvanian subperiod, followed by the breakup of Pangea in the Triassic, shaped the region. The subsequent seafloor spreading in the mid- and late Jurassic formed the Gulf of Mexico, leading to significant evaporite deposits and salt dome diapirs along the East Texas Gulf coast, which are crucial for oil reserves. Texas, far from an active plate tectonic boundary, experiences no volcanoes and few earthquakes.

Beyond its geology, Texas boasts an impressive array of wildlife, contributing significantly to its natural heritage. It is home to 65 species of mammals, 213 species of reptiles and amphibians, including the American green tree frog, and the greatest diversity of bird life in the United States, with 590 native species. At least 12 introduced species now reproduce freely in Texas, further adding to its ecological complexity. During the spring, Texas wildflowers, most notably the state flower, the bluebonnet, carpet highways throughout the state, presenting a breathtaking spectacle of natural beauty.

Texas, in its essence, embodies a narrative of continuous evolution, from its ancient indigenous civilizations and complex colonial past to its meteoric rise as an economic and demographic powerhouse in the modern era. Its landscapes, as vast and varied as its history, speak of resilience, transformation, and an enduring spirit that continues to beckon millions. This grand expanse, a testament to the diverse forces that shaped it, stands as a vibrant and indispensable pillar of the American story, ever growing and ever redefining its unique identity.