The English language, a vibrant and dynamic force, stands today as an undeniable global phenomenon, weaving its intricate threads through economies, cultures, and communication networks across every continent. Far more than just a means of expression, it serves as a common ground for billions, facilitating dialogue and discovery in an increasingly interconnected world. Its omnipresence might suggest a simple, straightforward lineage, yet the story of English is anything but—it’s a rich tapestry woven from centuries of migrations, conquests, and profound cultural exchanges.

This language, now spoken by an astonishing 1.457 billion people worldwide as of 2021, according to Ethnologue, has undergone a remarkable metamorphosis. From its humble beginnings as a collection of dialects spoken by Germanic settlers on the British Isles, English has absorbed, adapted, and innovated, transforming itself repeatedly to become the most geographically widespread language on Earth. Its journey is a testament to the power of linguistic evolution, mirroring the historical forces that shaped the societies in which it thrived.

Join us on an immersive exploration into the captivating past of the English language. We will delve into its ancient classifications, journey through pivotal historical periods, and uncover the crucial influences that forged its unique character. This deep dive will reveal how the language of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes blossomed into the multifaceted global lingua franca we recognize today, setting the stage for its eventual world dominance.

1. **English: A West Germanic Root within the Indo-European Family**

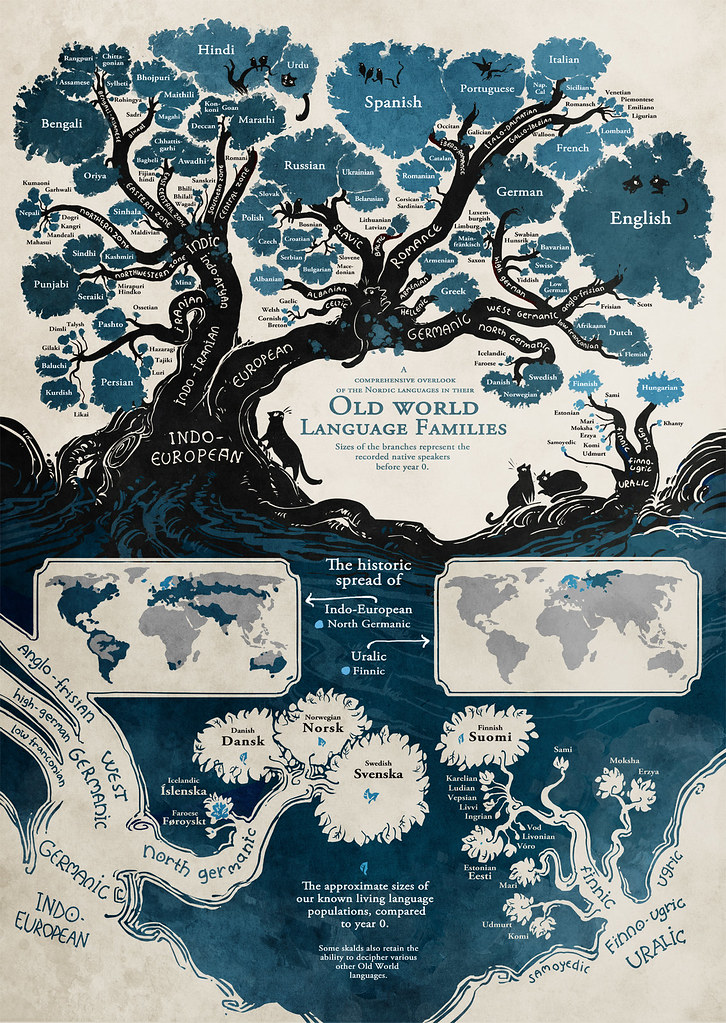

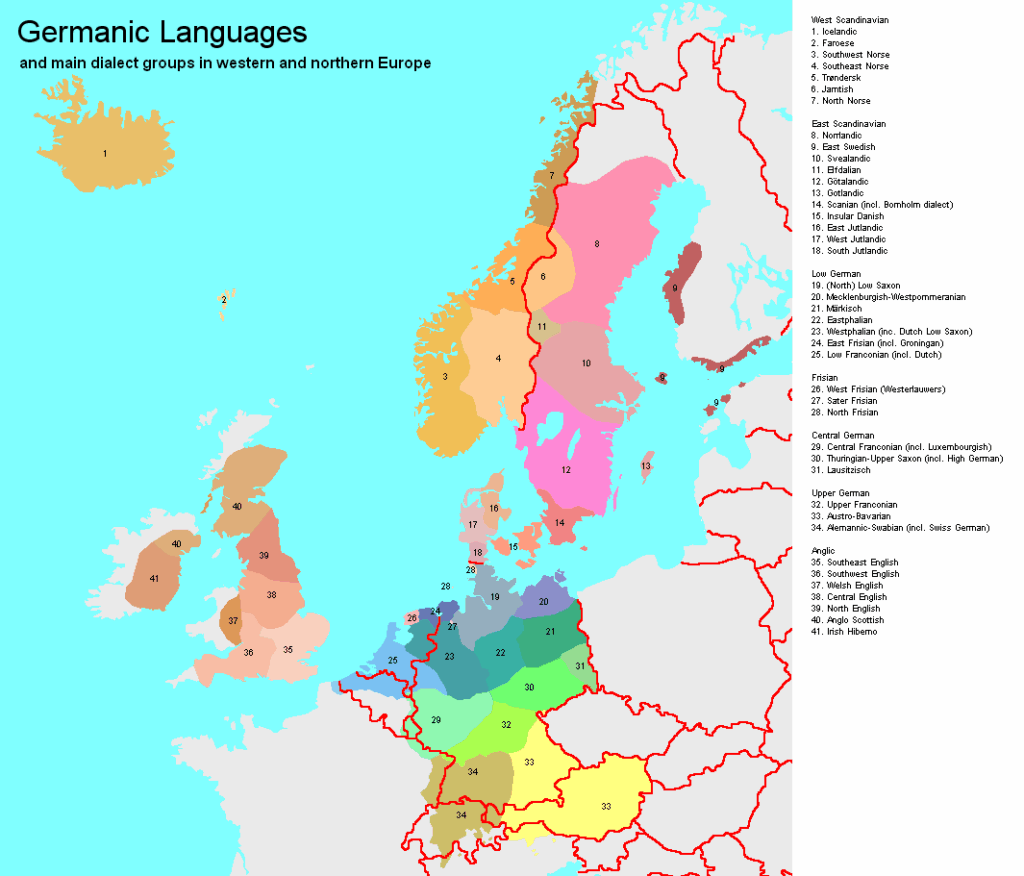

At its very core, English is classified as a West Germanic language, firmly rooted within the vast Indo-European language family. This lineage places it alongside siblings like German, Dutch, and Swedish, sharing a common ancestor known as Proto-Germanic. The tell-tale signs of this shared ancestry are evident in innovations such as the division of verbs into strong and weak classes, the distinctive use of modal verbs, and the pervasive sound changes affecting Proto-Indo-European consonants, famously encapsulated by Grimm’s and Verner’s laws.

More specifically, English is also categorized as an Anglo-Frisian language, a distinction earned from shared features with Frisian, particularly the palatalisation of consonants that were velar in Proto-Germanic. This close kinship is a fascinating glimpse into the early linguistic landscape along the North Sea coast. While once considered more intimately related than they are to other West Germanic tongues, modern scholarship suggests a shared common ancestor for the three Ingvaeonic languages—English, Frisian, and Low German—forming a dialect continuum that later diversified during the Migration Period around the 5th century.

2. **The Genesis: Old English and the Anglo-Saxons**

The earliest discernible form of the English language, Old English—often referred to as Anglo-Saxon—flourished from approximately 450 to 1150 AD. This foundational period saw the language develop from a collection of West Germanic dialects, typically grouped as Anglo-Frisian or North Sea Germanic. These dialects were originally spoken by the Germanic peoples historically known as the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, who hailed from the coasts of Frisia, Lower Saxony, and southern Jutland.

From the 5th century onwards, these Anglo-Saxons began to settle in Britain, coinciding with the collapse of Roman administration and economy there. By the 7th century, Old English had firmly established its dominance throughout Britain, effectively displacing the previously spoken Common Brittonic and British Latin, which ultimately left only minimal influence on the developing English language. It is from the Angles that both England and English derive their names, originally known as Ænglaland and Ænglisc, respectively.

Old English itself was not a monolithic entity; it was divided into four main dialects: the two Anglian dialects (Mercian and Northumbrian) and the two Saxon dialects (Kentish and West Saxon). Through the considerable influence wielded by the kingdom of Wessex and the educational reforms championed by King Alfred in the 9th century, the West Saxon dialect rose to prominence as the standard written variety. Illustrious works like the epic poem Beowulf are preserved in West Saxon, while the earliest English poem, Cædmon’s Hymn, offers a glimpse into Northumbrian. Intriguingly, while Modern English largely evolved from Mercian, the Scots language branched off from Northumbrian, highlighting the rich regional diversity of early English.

3. **Norse Influence: Shaping Early English**

Between the 8th and 11th centuries, a powerful external force significantly reshaped the English spoken in certain regions: contact with Old Norse, a North Germanic language. This transformative interaction was a direct consequence of several waves of Norsemen colonizing the northern British Isles in the 8th and 9th centuries, leading to sustained contact between Old English speakers and their Norse counterparts. The impact of Norse influence was particularly pronounced in the north-eastern varieties of Old English, especially those spoken within the Danelaw, the region surrounding York. These linguistic traces remain notably present in Scots and Northern English dialects even today.

Lindsey, located in the Midlands, emerged as a central hub of this Norse influence. Even after its incorporation into the Anglo-Saxon polity in 920, the linguistic features absorbed during this period continued to spread extensively throughout the region. A particularly pervasive element of Norse influence that persists across all varieties of English to this day is the third-person pronoun group beginning with ‘th-‘—namely ‘they,’ ‘them,’ and ‘their.’ These Norse pronouns effectively replaced their Anglo-Saxon equivalents, which began with ‘h-‘ (hie, him, hera), illustrating a fundamental shift in grammar.

Beyond pronouns, Old Norse gifted English a wealth of everyday vocabulary, often displacing native Anglo-Saxon equivalents. Words such as ‘give,’ ‘get,’ ‘sky,’ ‘skirt,’ ‘egg,’ and ‘cake’ are all testament to this rich linguistic exchange. During this era, it’s believed that Old Norse maintained a considerable degree of mutual intelligibility with certain dialects of Old English, especially the northern ones. This fascinating linguistic fluidity suggests a time when commoners from parts of northern England and Scandinavia could converse with relative ease, fostering a unique cultural and linguistic blend.

4. **The Norman Conquest: Birth of Middle English and French Lexical Impact**

The year 1066 marked a cataclysmic turning point in English history, both politically and linguistically, with the Norman Conquest of England. This seminal event is widely regarded as the beginning of the Middle English period, fundamentally redirecting the language’s developmental trajectory over the ensuing centuries. The new Norman rulers introduced their native tongue, a form of Old French known as Old Norman, which quickly began to intertwine with the existing Old English.

Over the decades following the conquest, a remarkable linguistic phenomenon unfolded: members of the middle and upper classes, whether of native English or Norman descent, progressively became bilingual. By 1150 at the latest, bilingual speakers constituted the majority of the English aristocracy, and monolingual French speakers had become a rare sight. The French spoken by this Norman elite in England gradually evolved into what is now known as the Anglo-Norman language, a distinct linguistic entity born of this historical fusion.

Crucially, the vast majority of the population—the lower classes—remained monolingual English speakers. Consequently, the primary influence of Norman French manifested as a lexical superstratum, injecting an immense array of loanwords into English. These new words predominantly pertained to prestigious social domains such as politics, law, and governance. For instance, the French word ‘trône’ made its debut, from which the English word ‘throne’ is directly derived, signifying a shift in power and vocabulary. Moreover, Middle English underwent a significant simplification of its inflectional system, a process likely spurred by the need to reconcile the distinct inflectional patterns of Old Norse and Old English, both of which were morphologically similar but grammatically divergent. The distinction between nominative and accusative cases largely vanished, save for personal pronouns; the instrumental case was dropped entirely, and the use of the genitive case was largely confined to indicating possession. This simplification extended to the regularisation of many irregular inflectional forms and a gradual streamlining of the agreement system, leading to a less flexible word order than in Old English. By the 12th century, Middle English was fully developed, a rich amalgamation of Norse and French features, and continued to be spoken until the transition to Early Modern English around 1500. Literary masterpieces such as Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’ and Thomas Malory’s ‘Le Morte d’Arthur’ exemplify the vibrant literary landscape of this period, where regional dialects also proliferated in writing and were even cleverly employed for stylistic effect by authors like Chaucer.

5. **The Great Vowel Shift: Remaking English Pronunciation**

The period of Early Modern English, spanning roughly from 1500 to 1700, was profoundly characterized by a monumental linguistic transformation known as the Great Vowel Shift. This sweeping phonetic change fundamentally reshaped the pronunciation of English long vowels, leaving an indelible mark on the language we speak today. It was a classic example of a “chain shift,” where each individual vowel sound’s movement triggered a subsequent shift in another vowel within the system, creating a cascading effect across the entire vowel inventory.

During this shift, mid and open vowels were gradually raised in the mouth, while close vowels underwent a process of “breaking,” transforming into diphthongs. To grasp the magnitude of this change, consider specific examples: the word ‘bite,’ for instance, was originally pronounced much like the word ‘beet’ is spoken today. Similarly, the second vowel in ‘about’ was articulated closer to how the word ‘boot’ is pronounced in contemporary English. These dramatic alterations illustrate how deeply the soundscape of English was reformed during this pivotal era.

One of the most significant legacies of the Great Vowel Shift is the persistent irregularities found in English spelling. Many words retain their spellings from Middle English, even though their pronunciations shifted dramatically. This explains why English vowel letters often have pronunciations vastly different from the same letters in other languages, serving as a constant reminder of this historical phonetic upheaval. Even after the shift, some characteristics still differed from Modern English; for example, consonant clusters like /kn/, /ɡn/, and /sw/ in words such as ‘knight,’ ‘gnat,’ and ‘sword’ were still fully pronounced, highlighting the distinct phonetic flavor of Early Modern English.

6. **The Printing Press and Standardization in Early Modern English**

The Early Modern English period witnessed a significant ascent in the prestige of English, particularly in relation to Norman French, which had long held sway in official and aristocratic circles. This rise was notably evident during the reign of Henry V, a period when England began to assert itself more prominently. A crucial development in this linguistic shift occurred around 1430, when the Court of Chancery in Westminster, a central administrative body, began to adopt English for its official documents.

This move heralded the emergence of a new standard form of Middle English, which became known as Chancery Standard. This particular dialect developed primarily from the speech patterns of London and the East Midlands, regions that were growing in economic and political importance. The adoption of this standard by such a prestigious institution provided a powerful impetus for its spread and acceptance across the realm, laying the groundwork for greater linguistic uniformity.

However, the true catalyst for widespread linguistic standardization arrived in 1476 with William Caxton. He introduced the printing press to England, a revolutionary technology that transformed the dissemination of written material. By publishing the first printed books in London, Caxton exponentially expanded the influence and reach of the Chancery Standard. The printed word provided a consistent visual representation of the language, gradually solidifying spelling, grammar, and vocabulary norms across diverse regions. This standardization, fueled by the printing press, played a critical role in unifying the language and setting the stage for the global spread of Modern English. The literary giants of this era, such as William Shakespeare, whose works continue to define the language, and the monumental 1611 King James Version (KJV) of the Bible, are prime examples of Early Modern English, showcasing its distinct grammatical features and evolving lexicon.

7. **Classification and Unique Divergence from Continental Germanic Languages**

English’s classification as a Germanic language is unequivocal, solidified by a suite of shared innovations with its continental cousins like Dutch, German, and Swedish. These innovations are compelling evidence that all these languages ultimately descended from a single common ancestor: Proto-Germanic. Key features that bind them include the characteristic division of verbs into strong and weak classes, the distinctive use of modal verbs (such as ‘can,’ ‘may,’ ‘must’), and a series of predictable sound changes affecting Proto-Indo-European consonants, famously codified by Grimm’s and Verner’s laws. These shared linguistic fingerprints confirm English’s deep Germanic heritage.

Furthermore, English is also specifically classified as an Anglo-Frisian language, a sub-grouping that highlights its particularly close historical ties to Frisian. This closer relationship is evidenced by shared phonetic shifts, such as the palatalisation of consonants that were originally velar in Proto-Germanic. This shared evolution paints a picture of a dialect continuum along the North Sea coast in the 5th century, from which English, Frisian, and Low German ultimately diverged into distinct languages during the Migration Period.

However, a fascinating aspect of English’s linguistic journey is its profound divergence from the continental Germanic languages. Much like Icelandic and Faroese, the development of English on the British Isles geographically isolated it from the continuous influences and linguistic shifts occurring on the European mainland. This isolation allowed English to evolve along its own unique trajectory, leading to significant differences in vocabulary, syntax, and phonology. Consequently, English is no longer mutually intelligible with any continental Germanic language, despite sharing a common ancestor. While some languages, such as Dutch and Frisian, still exhibit strong affinities with English, particularly with its earlier stages, the centuries of independent evolution have undeniably created distinct linguistic landscapes.

Having journeyed through the intricate historical tapestry of the English language, from its ancient Germanic roots to the profound shifts brought by Norse and French influences, and the critical standardization fostered by the printing press, we now turn our gaze to its contemporary landscape. Modern English, a vibrant and ever-evolving entity, extends its reach across the globe, touching every facet of human endeavor. Its remarkable journey has transformed it into an unparalleled international lingua franca, shaping communication, culture, and commerce on a truly global scale.

This section will illuminate the expansive geographical distribution of Modern English, explore the various ‘circles’ of its speakers, and delve into its indispensable role as the primary language of diplomacy, science, and the digital world. Furthermore, we will uncover some of the unique phonological characteristics that define contemporary English, distinguishing it from its ancestral forms and sister languages. The story of English in the modern era is one of unprecedented global presence, a testament to its adaptability and the historical forces that propelled it to its current standing.

8. **The Global Reach of Modern English: A Worldwide Phenomenon**

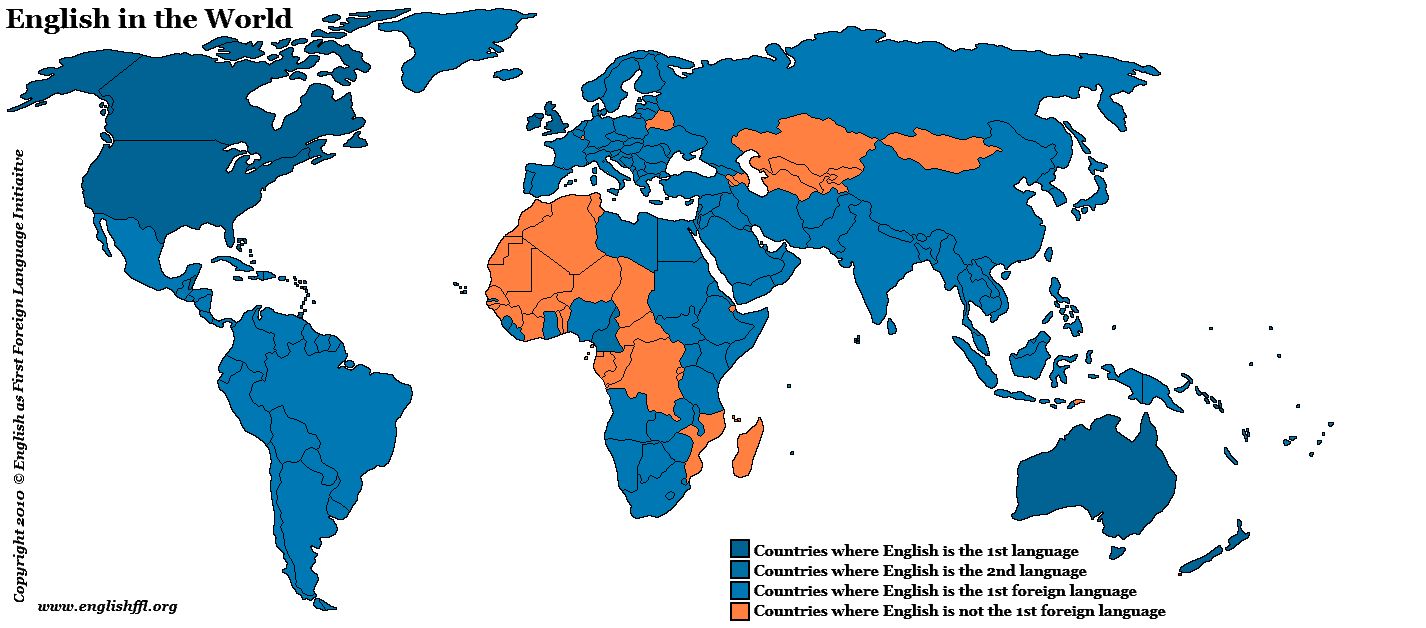

In the 21st century, English stands as a language of unparalleled global reach, spoken and written more widely than any language in human history. Its ascent to this pre-eminent position is largely attributable to the enduring global influences of the former British Empire, succeeded by the Commonwealth of Nations, and the significant economic and cultural sway of the United States. This linguistic dominance has not been a swift, sudden phenomenon, but rather a gradual expansion cultivated over centuries of trade, exploration, and cultural exchange.

As of 2021, Ethnologue estimates that there are over 1.457 billion English speakers worldwide, solidifying its status as the most spoken language globally. This impressive figure includes approximately 380 million native (L1) speakers and a staggering 1.077 billion second-language (L2) speakers. This substantial number of second-language speakers, surpassing native speakers, highlights English’s unique role as the most widely learned second language in the world, underscoring its practical utility and perceived value across diverse communities.

9. **Official Status and Geographical Distribution**

English’s widespread adoption is further evidenced by its official or co-official status in 57 sovereign states and 30 dependent territories, making it the most geographically widespread language on Earth. In countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, English functions as the dominant language due to historical circumstances, even without being explicitly defined by law. This de facto dominance underscores its deep integration into the societal fabric of these nations.

Beyond national borders, English has transcended its origins to become a co-official language of pivotal international bodies. It holds this esteemed position within the United Nations, the European Union, and numerous other international and regional organizations. This pervasive official presence in global governance and cooperation highlights its function as a crucial facilitator of international communication and diplomacy, enabling dialogue and understanding across diverse linguistic backgrounds.

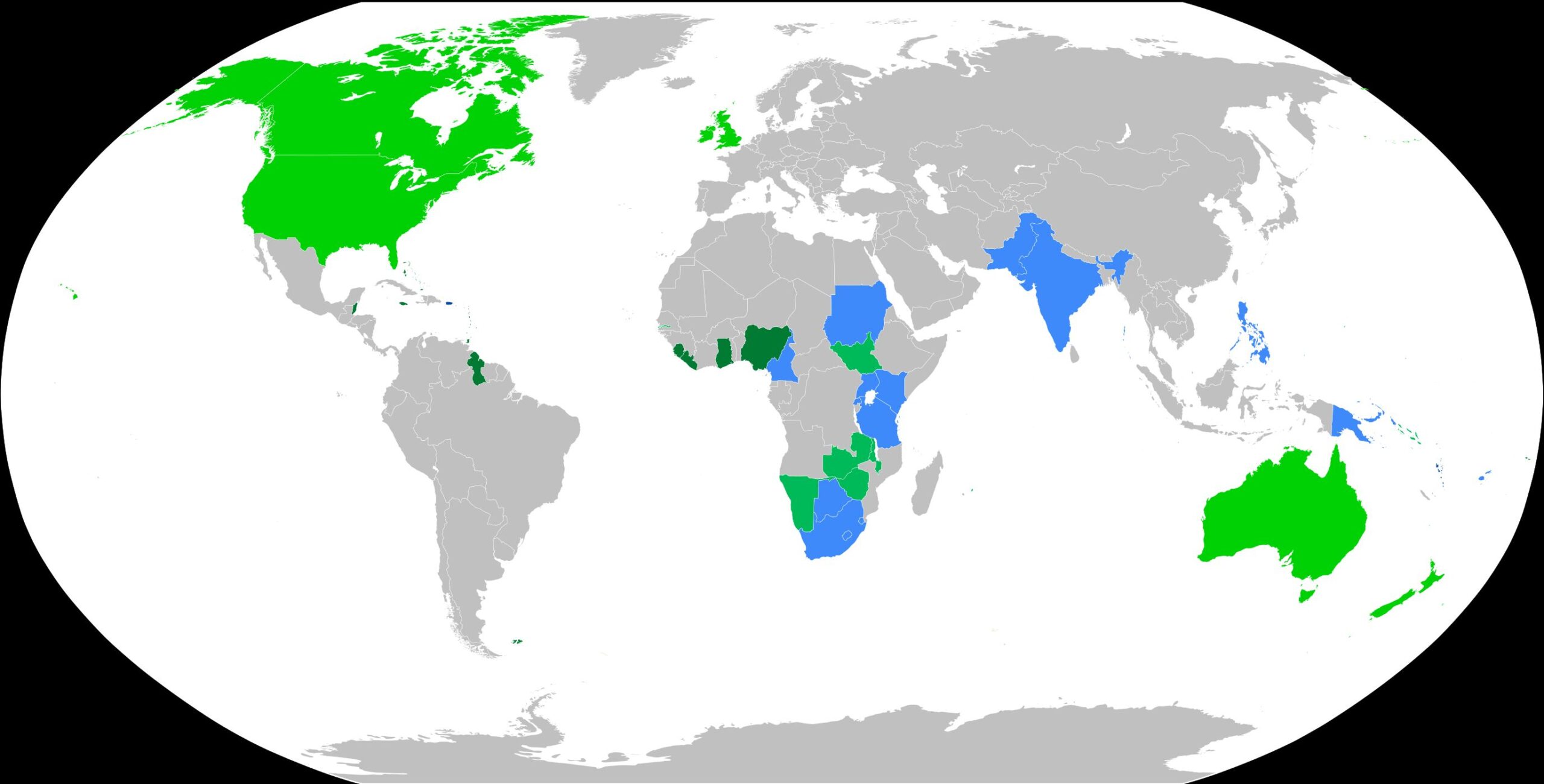

10. **Braj Kachru’s Three Circles Model: Mapping English Usage**

To better understand the multifaceted global presence of English, linguist Braj Kachru proposed a widely recognized ‘three circles model’ categorizing countries based on how English is used within them. This model provides a nuanced framework for appreciating the diverse roles English plays across the world. The ‘Inner-circle’ countries are those with substantial communities of native English speakers, forming the traditional base from which the language has radiated globally.

These Inner-circle nations include the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, Canada, Ireland, and New Zealand, where the majority of the population speaks English as a first language. South Africa also features in this circle, with a significant minority speaking English as their native tongue. The sheer numbers are compelling: the United States leads with at least 231 million native speakers, followed by the United Kingdom (60 million), Canada (19 million), Australia (at least 17 million), South Africa (4.8 million), Ireland (4.2 million), and New Zealand (3.7 million). In these societies, English is primarily acquired from parents, and local people or immigrants who speak other languages learn it for daily communication, reinforcing its centrality.

11. **The Outer and Expanding Circles: English as a Second and Foreign Language**

Moving beyond the Inner Circle, the ‘Outer-circle’ countries comprise nations with a smaller proportion of native English speakers but where English is widely used as a second language. These include countries such as the Philippines, Jamaica, India, Pakistan, Singapore, Malaysia, and Nigeria. In these regions, English serves crucial functions in education, government administration, and domestic business, often being the medium of instruction in schools and facilitating official interactions.

Within the Outer Circle, varieties of English can range widely, from English-based creole languages to more standard forms, reflecting the complex linguistic interactions within these diverse societies. Many speakers in these countries acquire English through day-to-day exposure, broadcast media, and formal schooling, demonstrating its organic integration into their daily lives. The ‘Expanding-circle’ encompasses countries where English is primarily taught as a foreign language, and while it may not have official or widely ingrained secondary status, a significant portion of the population learns it for various purposes.

For instance, in the Netherlands and several other European nations, a large majority of the population demonstrates proficiency in English, often utilizing it for communication with foreigners and in higher education. A 2012 Eurobarometer poll, conducted when the UK was still an EU member, revealed that 38 percent of EU respondents outside the official English-speaking countries could speak English well enough for a conversation, illustrating its pervasive influence even in regions where it is not a national language. These classifications, however, remain dynamic, with country memberships and the distinctions between English as a first, second, or foreign language often evolving over time.

12. **English as the Pre-eminent Global Lingua Franca**

Modern English is unequivocally described as the first global lingua franca, a language adopted by speakers of different native languages for common communication. Its dominance extends across numerous critical domains: newspaper and book publishing, international telecommunications, scientific research and publishing, international trade, logistics, tourism, aviation, entertainment, and the Internet. This pervasive role signifies its essential function as a bridge for global interaction and collaboration.

The language achieved parity with French as a diplomatic language by the negotiations of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. By the conclusion of World War II and the founding of the United Nations, English had ascended to preeminence, becoming one of the six official languages of the UN. Today, it stands as the main worldwide language of diplomacy and international relations. Furthermore, countless other global and regional international organizations, including the International Olympic Committee, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), specify English as a working or official language, even when most member states are not majority native English-speaking countries. English also forms the foundation for critical controlled natural languages like Seaspeak and Airspeak, which are indispensable for international seafaring and aviation.

13. **The Economic and Cultural Imperative for Learning English**

The global influence of English is not merely an academic or political phenomenon; it is deeply intertwined with economic and personal aspirations. English is the most frequently taught foreign language globally, and most individuals learn it for profoundly practical reasons, often linking proficiency to better employment opportunities and an increased quality of life. This pragmatic motivation fuels its continued spread and adoption across diverse communities.

Working knowledge of English has become an increasingly essential requirement in various professional fields, notably medicine and computing, where it serves as the primary language for innovation, research, and communication. Although it once shared prominence with French and German in scientific research, English now overwhelmingly dominates the field. Its importance in scientific publishing is stark: over 80 percent of scientific journal articles indexed by Chemical Abstracts in 1998 were in English, a figure that rose to 90 percent for all natural science publications by 1996, and 82 percent for humanities publications by 1995. This widespread adoption underscores its role as the de facto language of global scholarship.

As decolonization unfolded across the British Empire in the mid-20th century, many newly independent nations chose to retain English as an official language, not as a remnant of colonialism, but as a practical solution to linguistic diversity and a pathway to economic progress. India serves as a prime example, where English is one of the official languages, and the country has become the third-largest publisher of English-language books globally, after the US and UK. This pragmatic embrace has fostered vibrant English-speaking communities, such as the ‘Afro-Saxon’ community in Africa, which unites speakers from different countries. The future of English is widely seen as continuing its function as a koiné language, with a standard form that unifies speakers worldwide.

14. **The Unique Phonological Landscape of Modern English**

While English exhibits remarkable global consistency in its written form, its spoken phonology and phonetics vary considerably across different dialects, typically without hindering mutual communication. This phonological variation can affect the inventory of phonemes—the distinct speech sounds that differentiate meaning—while phonetic variation refers to differences in how those phonemes are pronounced. To illustrate, we often reference Received Pronunciation (RP) in the United Kingdom and General American (GA) in the United States as standard varieties for comparative analysis.

Most English dialects share a core set of 24 (or potentially 26, if marginal sounds are included) consonant phonemes. Within this consonant system, distinctions arise between fortis (strong) and lenis (weak) obstruents, which often appear in pairs like /p b/, /tʃ dʒ/, and /s z/. Fortis obstruents, such as /p/, /tʃ/, and /s/, are pronounced with greater muscular tension and breath force and are always voiceless. Conversely, lenis consonants, such as /b/, /dʒ/, and /z/, are pronounced with less force, are partly voiced at the beginning and end of utterances, and fully voiced between vowels. Fortis stops, like /p/, exhibit additional articulatory features in most dialects; they are aspirated, [pʰ], when alone at the start of a stressed syllable (e.g., ‘pin’), often unaspirated in other contexts (e.g., ‘spin’), and frequently unreleased, [p̚], or pre-glottalised, [ʔp], at the end of a syllable (e.g., ‘nip’). A vowel preceding a fortis stop in a single-syllable word is typically shortened, as seen in ‘nip’ versus ‘nib,’ which highlights a subtle but phonemically significant difference.

Further intricacies abound, such as the allophones (pronunciation variants) of the lateral approximant /l/. In RP, it has a clear or plain [l] sound, as in ‘light,’ while in other positions, such as at the end of a syllable, it becomes a dark or velarized [ɫ] sound, as in ‘full.’ General American, by contrast, tends to use the dark [ɫ] in most contexts. Additionally, all sonorants (liquids like /l, r/ and nasals like /m, n, ŋ/) undergo devoicing when they follow a voiceless obstruent, as heard in ‘clay’ [kl̥eɪ̯] or ‘snow’ [sn̥əʊ̯]. They also become syllabic when following a consonant at the end of a word, creating sounds like those in ‘paddle [ˈpad.l̩] or ‘button’ [ˈbʌt.n̩]. These phonetic nuances contribute to the rich and varied soundscape of Modern English, allowing for a dynamic interplay of regional accents while maintaining overall intelligibility across its vast global community.

As we conclude this comprehensive exploration, it becomes abundantly clear that the English language is not merely a linguistic artifact but a living, breathing testament to human history, migration, and interconnectedness. From its humble origins in the Germanic dialects of ancient settlers to its current status as the world’s most widespread language, English has continuously absorbed, adapted, and reinvented itself. Its journey is a compelling narrative of survival and triumph, of influences both violent and subtle, shaping its grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation. Today, as a global lingua franca, English facilitates unprecedented levels of communication, commerce, and cultural exchange, bridging divides and opening doors across every continent. It is a language that embodies dynamism, reflecting the ongoing evolution of human society itself, and promising an equally fascinating future as it continues to adapt to the ever-changing global landscape.