In an age brimming with information, where every swipe and click promises insight, a fundamental question echoes louder than ever before: What is truth? It’s a question that, as the context reminds us, can spark fascinating conversations and, in some circles, even evoke laughter, scorn, or derision. Yet, the concept of truth, far from being an outdated relic, remains the bedrock of a thriving society and a fulfilling life. We are living through a period where the very idea of truth has fallen on hard times, and the consequences of this societal shift are profoundly impacting human interactions, trust, and our collective well-being. But just as we seek to nourish our bodies with wholesome, unprocessed foods for sustained health, so too must we nourish our minds with genuine understanding, cultivating an appetite for truth that empowers us to navigate the complexities of our world.

The human need for truth is not a mere intellectual curiosity; it is a primal necessity. Imagine trying to plan your day, build a home, or even cross a street without accurate information about the world around you. Believing what is not true is apt to spoil people’s plans and may even cost them their lives. Conversely, telling what is not true can result in severe legal and social penalties. Our very ability to thrive, to build, and to connect depends on a shared understanding of what is real, what is factual, and what stands as truly valid. The dedicated pursuit of truth characterizes the good scientist, the good historian, and the good detective—each striving to align their understanding with what genuinely “is.” This profound gravity and central place in people’s lives compel us to ask: what exactly *is* truth?

Our journey into the essence of truth begins with a classic suggestion, one that resonates deeply with common sense. From the venerable wisdom of Aristotle (384–322 BCE) comes a definition that has anchored philosophical thought for millennia: “To say of what is that it is, or of what is not that it is not, is true.” This seemingly straightforward statement forms the germ of what philosophers call the correspondence theory of truth. In essence, it proposes that truth is a property of statements, beliefs, or propositions that “agree with the facts” or “state what is the case.” The world provides “what is” or “what is not,” and a true saying or thought simply mirrors this external reality.

This intuitive notion finds echoes across centuries and cultures. The Persian polymath Avicenna viewed truth as “what corresponds in the mind to what is outside it,” while Thomas Aquinas spoke of truth as the “adequation of things and the intellect” (adæquatio rei et intellectus). For centuries, philosophers largely agreed that thought or language is true if it corresponds to an independent reality. This perspective offers a comforting sense of objectivity: truth exists outside of us, and our task is merely to align our internal representations with it. It suggests a clear, discoverable reality that our minds can accurately perceive and articulate.

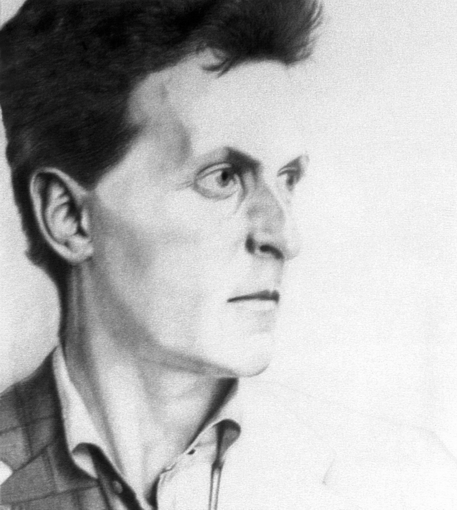

However, as appealing as this simplicity is, the correspondence theory, in its bare form, can be “little more than a platitude and far less than a theory.” It essentially rephrases “that’s true” into “that corresponds with the facts,” without truly explaining what “facts” are or how “correspondence” works. This is where the philosophical waters begin to deepen. Many thinkers have questioned whether an acceptable explanation of facts and correspondence can truly be given. The Austrian-born philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, for instance, pointed out the peculiar nature of facts: unlike physical structures, facts do not have spatial locations. You can move the Eiffel Tower, but the fact that the Eiffel Tower is in Paris cannot be moved.

This distinction highlights the elusive nature of what we consider a “fact” and challenges the idea of facts as simple, tangible structures in the world. Furthermore, critics argue that the very idea of “what the facts are” in a given situation is inseparable from our sincere beliefs about that situation—beliefs that we already take to be true. This perspective suggests that we don’t first form a belief and then “step outside” of it to see if it corresponds with independent facts. Instead, our processes of checking and verifying beliefs involve bringing up *further* beliefs and perceptions, and assessing the original belief in light of these. In practical investigations, what guides our beliefs isn’t a raw, uninterpreted world, but rather how we interpret the world, how we select and conceptualize “the facts.”

Our minds, these critics propose, don’t perceive reality as it is, but “only as it can, filtering, distorting, and interpreting it.” This crucial observation leads to profound questions about whether we can ever truly access an “independent reality” untainted by our interpretive frameworks. Modern thought, exemplified by Michel Foucault, even speaks of “regimes of truth,” suggesting that truth is not a singular, objective entity, but constructed by social and cultural processes, influenced by individual desires and dispositions, and potentially reflecting categories like race, sexuality, or mental disorder that may not reflect biological or metaphysical realities. This challenges the straightforward, mirror-like correspondence that Aristotle first envisioned.

The critiques of the correspondence theory, particularly those emerging from the mid-19th century, spurred philosophers to explore alternative understandings of truth. Rather than focusing on individual sentences or assertions, some began to concentrate on larger theories and systems of belief. This shift led to the development of the coherence theory of truth. On this view, truth is seen as a feature of an “overall body of belief considered as a system of logically interrelated components”—often referred to as the “web of belief.” An individual belief within such a system is considered true if it “sufficiently coheres with, or makes rational sense within, enough other beliefs.” Alternatively, an entire belief system is deemed true if it exhibits sufficient internal coherence.

This approach was championed by British idealists like F.H. Bradley and H.H. Joachim, who, consistent with their idealistic philosophy, rejected the notion of mind-independent facts against which beliefs could be judged. For them, truth wasn’t about matching an external reality, but about internal consistency and logical harmony within one’s own conceptual framework. It offers a powerful model for how scientific theories function, for instance—a theory earns its validity by making consistent predictions, enabling control over phenomena, or simplifying and unifying previously disconnected observations. It’s about how well all the pieces of our knowledge fit together into a seamless whole.

However, the coherence theory faces its own significant challenges. Bertrand Russell, the English philosopher and logician, famously pointed out a critical flaw: nothing inherent in the coherence theory prevents the existence of “many equally coherent but incompatible belief systems.” Yet, logically, “at best only one of them can be true.” If internal consistency is the sole criterion, then a perfectly constructed fictional world could be considered “true” within its own confines, even if it bore no relation to reality. This suggests that coherentism might trap human beings “in the sealed compartment of their own beliefs, unable to know anything of the world beyond.” While a coherent system might *suggest* something is true, it doesn’t definitively tell us “what truth actually is.” It could still be “a giant fiction, entirely detached from reality.

Recognizing these limitations, some theorists introduced a pragmatic or utilitarian lens to evaluate belief systems. This led to the pragmatic theory of truth, which posits that even if multiple systems are internally coherent, some will inevitably be “much more useful than others.” This idea draws an analogy to Darwinian natural selection: the more useful systems are expected to “survive,” while less effective ones gradually “go extinct.” The replacement of Newtonian mechanics by relativity theory is often cited as a powerful example of this process—relativity wasn’t just more coherent; it was demonstrably more useful in making accurate predictions and understanding the universe.

The 19th-century American pragmatist philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce encapsulated this view beautifully, stating: “The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate, is what we mean by the truth, and the object represented in this opinion is the real.” Peirce’s perspective places paramount importance on scientific inquiry, experimentation, and continuous theorizing, identifying truth as the “imagined ideal limit of their ongoing progress.” This “hard-headed” approach appeals to our desire for practical outcomes and tangible results. William James echoed this, suggesting that “the truth is ‘only the expedient in the way of our thinking, just as the right is only the expedient in the way of our behaving.’” If something works, it may well be true; if it doesn’t, it most probably isn’t.

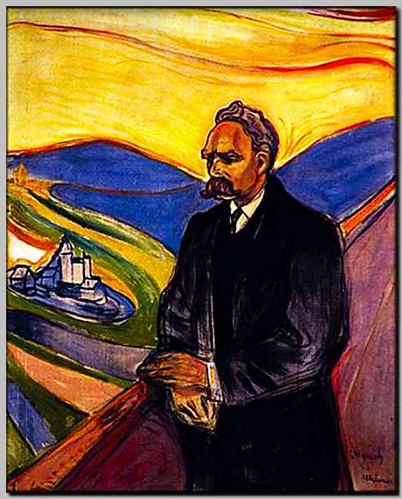

Yet, the pragmatic theory also invites questions. What if something “works for me but not for you”? Is it then “true for me but not for you”? This line of reasoning, when pushed to its extreme, can lead to problematic conclusions. Friedrich Nietzsche, for example, famously asserted that “the falseness of a judgment is not necessarily an objection to a judgment … The question is to what extent it is life-advancing, life-preserving, species-preserving, perhaps even species-breeding …” For Nietzsche, truth was essentially power, and power was truth, making him, as the context notes, “the natural ally of two-penny tyrants.” This raises crucial concerns about the ethical implications of a purely utilitarian view of truth—at what cost does “successful action” come, and for whom? Is short-term expediency always aligned with genuine truth? The late 20th-century philosopher Richard Rorty even advocated “retiring the notion of truth in favour of a more open-minded and open-ended process of indefinite adjustment of beliefs,” a process he felt would have its own utility even without a final, absolute endpoint. This pragmatic flexibility, while appealing in its openness, has opened the door to varying degrees of skepticism about the very notion of truth itself, contributing to the “hard times” that truth has fallen on.

While philosophical inquiry offers invaluable frameworks for understanding truth, its journey often circles back to a profound realization: for many, especially within a theological context, truth finds its ultimate source and definition in something far grander than human constructs or observations. Ask anyone today, “What is truth?” and you’re indeed sure to start an interesting conversation. But to truly grasp its essence, we must look beyond secular debates and delve into a perspective that has anchored billions throughout history.

One of the most profound and eternally significant questions in the Bible was posed by an unbeliever, Pontius Pilate, who turned to Jesus in His final hour and asked, “What is truth?” This was not a serious philosophical inquiry but a rhetorical, cynical response to Jesus’s declaration: “I have come into the world to testify to the truth.” Two millennia later, this very cynicism breathes throughout the world. Some dismiss truth as a “power play,” a “metanarrative constructed by the elite for the purpose of controlling the ignorant masses.” For others, truth is purely “subjective,” a realm of individual preference and opinion. Still others view it as a “collective judgment,” the “product of cultural consensus,” or even flatly “deny the concept of truth altogether.

Beyond direct revelation, Scripture also affirms that God reveals basic truths about Himself through nature. “The heavens declare His glory” (Psalm 19:1), and His “invisible attributes (such as His wisdom, power, and beauty) are on constant display in what He has created” (Romans 1:20). A foundational “knowledge of Him is inborn in the human heart” (Romans 1:19), and a “sense of the moral character and loftiness of His law is implicit in every human conscience” (Romans 2:15). These are presented as “universally self-evident truths.” According to Romans 1:20, any “denial of the spiritual truths we know innately always involves a deliberate and culpable unbelief.” Proof of these basic truths stamped on the human heart can be found throughout “the long history of human law and religion.” To suppress this truth is to dishonor God, displace His glory, and incur His wrath (vv. 19-20).

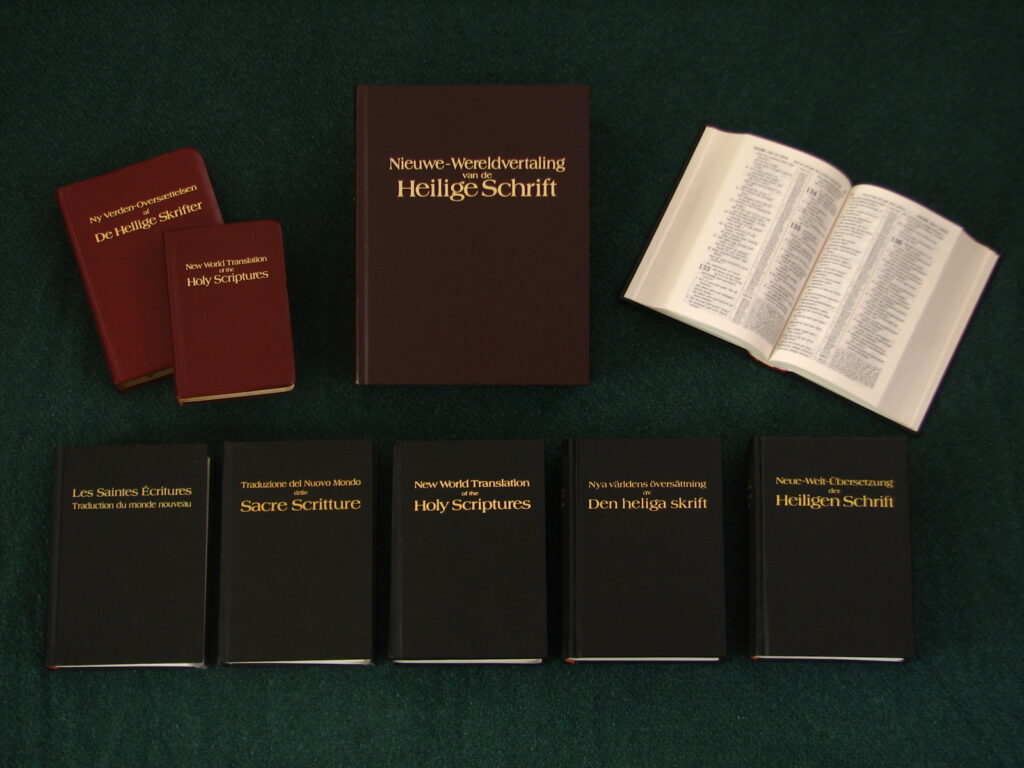

Yet, while nature and conscience reveal much, “the only infallible interpreter of what we see in nature or know innately in our own consciences is the explicit revelation of Scripture.” Since Scripture also uniquely provides “the way of salvation, entrance into the kingdom of God, and an infallible account of Christ,” the Bible stands as “the touchstone to which all truth claims should be brought and by which all other truth must finally be measured.” This establishes a hierarchy of truth, where divine revelation serves as the ultimate standard.

An obvious, yet profound, corollary of this theological understanding is that “truth means nothing apart from God.” It “cannot be adequately explained, recognized, understood, or defined without God as the source.” As the eternal, self-existent Creator, He is “the fountain of all truth.” The text challenges us: “If you don’t believe that, try defining truth without reference to God, and see how quickly all such definitions fail.” The moment one truly ponders the essence of truth, one is “brought face to face with the requirement of a universal absolute—the eternal reality of God.” Conversely, the “whole concept of truth instantly becomes nonsense (and every imagination of the human heart therefore turns to sheer foolishness) as soon as people attempt to remove the thought of God from their minds.

The apostle Paul, in Romans 1:21-22, vividly traces this “relentless decline of human ideas”: “Although they knew God, they did not glorify Him as God, nor were thankful, but became futile in their thoughts, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Professing to be wise, they became fools.” This paints a stark picture of the intellectual and moral consequences when truth is severed from its divine anchor. Furthermore, there are serious moral implications. Paul continued, “Even as they did not like to retain God in their knowledge, God gave them over to a debased mind, to do those things which are not fitting” (Romans 1:28). Abandoning a biblical definition of truth, the context warns, leads to “unrighteousness” as “the inescapable result.” The widespread acceptance of “homosexuality, rebellion, and all forms of iniquity that we see in our society today” is presented as “a verbatim fulfillment of what Romans 1 says always happens when a society denies and suppresses the essential connection between God and truth.

If we reflect on this with any degree of sobriety, it becomes clear that even “the most fundamental moral distinctions—good and evil, right and wrong, beauty and ugliness, or honor and dishonor—cannot possibly have any true or constant meaning apart from God.” This is because “truth and knowledge themselves simply have no coherent significance apart from a fixed source, namely, God.” God “embodies the very definition of truth,” making every truth claim apart from Him preposterous.”

Indeed, thousands of years of human philosophy, with its “elaborate epistemologies,” have been “proposed and methodically debunked one after another.” The “very best of human philosophers (Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Locke, Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Marx, James, and others) have all utterly failed to account for truth and the origin of human knowledge apart from God.” The most valuable lesson humanity ought to have learned from this vast philosophical endeavor is precisely “that it is impossible to make sense of truth without acknowledging God as the necessary starting point.

Ultimately, the article asserts, “Truth is not subjective, it is not a consensual cultural construct, and it is not an invalid, outdated, irrelevant concept.” Instead, “Truth is the self-expression of God.” As such, truth is not merely an intellectual concept; it is “theological,” it is “the reality God has created and defined, and over which He rules.” Consequently, truth is profoundly “a moral issue for every human being.” How each person chooses to respond to the truth God has revealed carries “eternal significance.” To reject and rebel against this divine truth is portrayed as leading to “darkness, folly, sin, judgment, and the never-ending wrath of God.” Conversely, “to accept and submit to the truth of God is to see clearly, to know with certainty, and to find life everlasting.” This foundational exploration provides the mental nourishment needed to cultivate a genuine understanding of truth, preparing us for the practical challenges of discernment in our modern world.

After delving into the foundational pillars of truth, from ancient philosophical constructs to its profound theological moorings, we now confront the undeniable reality of our contemporary landscape: a world where truth, once considered a fixed star, often feels like a flickering candle in a storm of competing narratives. Indeed, the very question, “What is truth?” — once a philosophical inquiry, as we’ve noted, or even a cynical rhetorical flourish by figures like Pontius Pilate — now resonates with an unsettling urgency in our daily lives. We live in an age where information, disinformation, and outright falsehoods intertwine, creating a veritable labyrinth of deception that challenges our ability to discern authentic reality. Yet, armed with the wisdom gleaned from both rigorous inquiry and divine revelation, we are not left without a compass; rather, we are called to cultivate a discerning spirit, much like someone carefully curating their diet for optimal health.

This skepticism about truth that Pilate embodied two millennia ago has, regrettably, become a pervasive cynicism in our modern world. Today, the notion of truth is often dismissed as a “power play,” nothing more than a “metanarrative constructed by the elite for the purpose of controlling the ignorant masses.” Others reduce it to something purely “subjective,” a mere realm of individual preference and opinion, or a “collective judgment,” born from cultural consensus. Alarmingly, some even flatly “deny the concept of truth altogether.” This erosion of a shared objective reality has tangible, corrosive effects on societal trust and individual well-being, leaving many feeling adrift in a sea of uncertainty.

This contemporary challenge is perhaps most vividly illustrated by the phenomena of “fake news,” outright lies, and what has been aptly termed “bullsh*t.” We’ve witnessed prominent figures, like Rudy Giuliani, claiming that “‘truth isn’t truth’,” and Kellyanne Conway presenting the public with “alternative facts.” Across the Atlantic, during the Brexit referendum, Michael Gove famously declared that people “have had enough of experts.” While the term “fake news” has been co-opted and broadened in recent times, its essence – intentionally false information designed to deceive – is far from new. The historical anecdote of Mark Antony, who fatally stabbed himself based on Cleopatra’s self-serving rumor, is a stark reminder that calculated falsehoods have always been a weapon in the human arsenal, with devastating consequences.

However, the internet age has supercharged the spread of such deception, transforming it into a global pandemic that “has spread like a disease.” We see its effects in swinging elections, fomenting social unrest, undermining institutions, and diverting political capital away from critical areas like health and education. The proliferation of “slop-posting,” characterized by “absurd or mildly offensive” AI-generated memes and videos, further muddies the waters of reality. When such content is shared by figures of authority, like a sitting president posting a falsified video of a former president, it transcends mere “lame trolling.” It actively “mudd[ies] the waters on what is real, encouraging his supporters to believe everything and nothing.” In such an environment, the line between fact and fiction blurs to the point where, for some, the answer to “Did a woman in a bikini really catch a snake? Is Obama really going to be arrested?” may not even matter.

This casual disregard for factual accuracy represents a profound deviation from what we, as a society, have historically expected from leadership. A president, after all, “is supposed to be the ultimate consumer of facts, not a producer of falsehoods.” While leaders throughout history have undoubtedly misled or cited false evidence, there was usually a significant “price” to pay, sparking “huge scandal[s].” The shift towards a public sphere where AI-generated falsehoods are casually disseminated without serious repercussions signals a dangerous normalisation of deception, demanding a heightened sense of vigilance and discernment from every individual.

Amidst this digital deluge of fabricated narratives, there’s a compelling argument to be made for a deeper understanding of the nature of falsehood itself. The philosopher Harry Frankfurt offered a crucial distinction between a liar and a bullsh*tter. A liar, he explained, “must track the truth in order to conceal it.” They are “playing on opposite sides… in the same game” as truth-tellers, still acknowledging the authority of truth even as they defy it. In contrast, “The bullsh*tter ignores these demands altogether. He does not reject the authority of the truth, as the liar does, and oppose himself to it. He pays no attention to it at all.” Frankfurt concludes with a chilling observation: “By virtue of this, bullsh*t is a greater enemy of the truth than lies are.” This insight is vital for navigating our modern landscape; it suggests that the greatest threat isn’t always overt deception, but rather a pervasive indifference to truth altogether.

In a world seemingly dominated by noise and manufactured consent, the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard offers a provocative, yet ultimately encouraging, perspective: “Truth always rests with the minority, and the minority is always stronger than the majority, because the minority is generally formed by those who really have an opinion, while the strength of a majority is illusory, formed by the gangs who have no opinion—and who, therefore, in the next instant (when it is evident that the minority is the stronger) assume its opinion… while truth again reverts to a new minority.” This isn’t a call to embrace contrarianism for its own sake, but a powerful reminder that genuine conviction and a dedicated pursuit of truth, even when unpopular, possess an inherent strength that can ultimately shift the tide of public opinion. It emphasizes the active, intentional nature of seeking and holding onto truth.

This perspective naturally flows into a broader consideration of truth’s enduring value. Beyond its instrumental worth — that “truth tends to lead to successful action,” as exemplified by scientific advancements like sending a rocket to the moon — truth also possesses profound “intrinsic value.” The thought experiment of choosing between a life of limitless pleasure as a “brain in a vat” and a genuine human life, with all its inherent struggles, strongly suggests that most people would opt for the latter. This preference speaks to a deep human longing for authentic experience, for reality as it truly is, even when it is difficult. Truth is not just a means to an end; it is an end in itself, something intrinsically good and desirable, akin to the wholesome food we instinctively seek for our bodies.

The “long history of human law and religion” testifies to the “universally self-evident truths” that God has stamped on the human heart through nature and conscience. These innate understandings provide a starting point for discernment. However, the Bible asserts that “the only infallible interpreter of what we see in nature or know innately in our own consciences is the explicit revelation of Scripture.” It is “the touchstone to which all truth claims should be brought and by which all other truth must finally be measured.” This hierarchy of truth is not arbitrary; it’s a guide to what is truly real and reliable, much like a trusted recipe ensures a healthy and delicious meal.

To embrace this perspective is to move beyond the cynicism of our age and rediscover truth as a “moral issue for every human being.” It’s an invitation to align our thoughts and actions with the very fabric of reality as defined by its Creator. In a world awash with “alternative facts” and AI-generated fabrications, the path to authentic reality lies in a deliberate, conscious choice: to pursue truth not as a subjective preference or a mere social construct, but as the enduring, life-giving self-expression of God. This pursuit promises not only clarity and certainty in an uncertain world, but also the profound, liberating freedom that only genuine truth can provide. By anchoring ourselves in this ultimate source, we can confidently discern the real from the fabricated, ensuring that our minds, like our bodies, are nourished with what is truly wholesome and sustaining.