Remember the roar of the crowd, the flickering lights, and the magic unfolding on the silver screen? From the 1930s through the 1940s, Hollywood wasn’t just a place; it was a kingdom, meticulously built and fiercely governed by a select few. This was the era of the studio system, a period when motion-picture production transformed profoundly, and executives held sway over much of the creative process, shaping not just films, but American popular culture itself. It was a time of intense competition, financial peril, and dazzling innovation, all orchestrated by some truly unforgettable personalities.

At its heart, the studio system was a masterclass in private enterprise, driven by companies locked in vigorous competition during the Depression-ridden 1930s and war-torn 1940s. It consisted of the “Big Five”—Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Paramount, Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO), Warner Bros., and Twentieth Century-Fox—and the “Little Three” smaller organizations: Universal, Columbia, and United Artists. These titans of industry employed a strategy known as “vertical integration,” which essentially meant they controlled everything from the film’s initial production all the way to its exhibition in theaters. By the late 1930s, these eight studios were responsible for a staggering 95 percent of U.S. film rentals, giving their executives unprecedented power.

While some might view this extension of executive authority as an intrusion into the sacred creative process, for management, it was a necessary means to reduce costs and ramp up production. These were challenging times, marked by the Great Depression, which saw unemployment rates soar and movie attendance plummet, coupled with the rising specter of home entertainment like radio and later, television. Yet, amidst this maelstrom, certain studio bosses emerged as absolute masters, their names becoming synonymous with power, resilience, and the very fabric of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Let’s peel back the curtain and meet some of these remarkable figures who dominated the industry and whose influence echoed well into the 1950s.

1. **Louis B. Mayer (MGM)**When we talk about the ultimate Hollywood mogul, Louis B. Mayer’s name almost immediately springs to mind. As the paternalistic, flamboyant studio boss of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Mayer steered his studio through the treacherous waters of the Great Depression with surprisingly little difficulty. While the context explicitly states he was “certainly no model of efficient management,” his leadership coincided with MGM’s remarkable resilience during an era when other studios were floundering, grappling with immense debts incurred during the prosperous 1920s.

Mayer’s personal style and vision undoubtedly influenced MGM’s identity. The studio became synonymous with elegance and glamour, offering audiences a much-needed escape from the grim realities of the Depression. This strategy of lavish productions, even when other studios were cutting budgets, helped MGM maintain its allure and profitability. It was a gamble that paid off, ensuring that moviegoers continued to flock to theaters for a taste of fantasy.

Beyond the glitz, Mayer’s autocratic nature ensured a centralized control over operations, which was typical of the studio system. Despite his questionable efficiency, MGM’s consistent success, particularly through the difficult 1930s, highlights his ability to command and maintain a leading position for the studio, making it number one eleven years running from 1931–41. This sustained dominance speaks volumes about the power he wielded.

However, even a master of the system like Mayer eventually faced the shifting sands of Hollywood. While his reign was long and impactful, he was famously “sacked in 1951 from MGM,” a clear sign that the golden age of absolute studio boss power was drawing to a close, even if his legacy in shaping the grand MGM style remained indelible.

Read more about: Greta Garbo: Unveiling the Enigma – The Luminous Life and Profound Legacy of Hollywood’s Most Mysterious Star

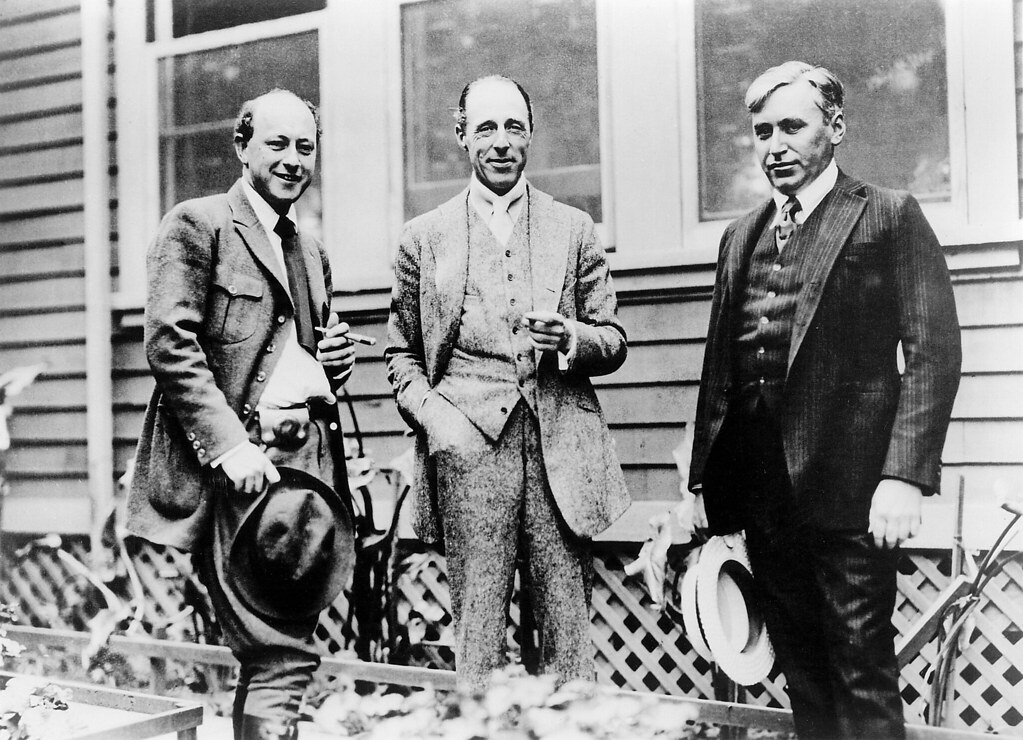

2. **Irving Thalberg (MGM)**Often seen as the creative counterpoint to Mayer’s more business-centric approach, Irving Thalberg was the “executive producer” whose “brief but brilliant tenure” at MGM cemented the studio’s reputation for quality and spectacle. Despite a “sickly physique,” Thalberg possessed a “dynamo of energy,” pouring himself into every aspect of film production, a dedication that tragically drove him to an early death in 1936 at the age of 37. Yet, his impact was profound and lasting.

Thalberg’s authority extended across the entire filmmaking spectrum. He “supervised production, from the hiring of screenwriters to the final editing of the film,” essentially crafting the artistic vision for MGM’s output. His commitment to quality was unwavering, and he famously pushed the studio to maintain an expensive payroll even “at a time when other studios cut their budgets.” This focus on investing in talent and production values set MGM apart, ensuring a level of polish and grandeur rarely matched.

The results of Thalberg’s demanding standards were truly impressive. Under his guidance, MGM provided audiences with a powerful antidote to the “doldrums of the Depression” through popular, lavish productions. Films like the South Seas saga “Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)” and the Victorian romance “The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934)” bore his distinct “personal imprint.” These were not just movies; they were events, offering escapism and high entertainment.

His early departure left a void, but the studio’s foundation was so strong that “after Thalberg’s death in 1936, MGM continued to attract large audiences.” His strategic leadership in an era of executive oversight proved that a single vision could elevate an entire studio, establishing a benchmark for production quality that defined a significant portion of Hollywood’s Golden Age. He was a master of shaping the creative output that drove the system.

Read more about: Greta Garbo: Unveiling the Enigma – The Luminous Life and Profound Legacy of Hollywood’s Most Mysterious Star

3. **Jack Warner (Warner Bros.)**If Louis B. Mayer embodied opulence, Jack Warner of Warner Bros. was the epitome of shrewd, hard-nosed efficiency. Described as “a somewhat heavy-handed version of Irving Thalberg,” Warner took direct control of studio operations, intervening at various stages of production. However, unlike Thalberg’s primary concern for quality, Warner “pressed for quick, efficient production,” always with an eye on the bottom line.

Warner’s notorious “cost-control methods seemed to work,” even if they made him “the subject of surreptitious humor among writers, directors, and actors.” Imagine a studio boss so dedicated to frugality that he would “personally switch off lights in studio bathrooms”! This relentless drive to hold down costs allowed Warner Bros. to cling to a “respectable prosperity in the 1930s,” despite not attempting to match MGM’s grandeur.

Warner Bros. distinguished itself by taking a huge risk on sound films in the 1920s, a gamble that “vaulted to the forefront in the 1930s.” Under Jack Warner’s leadership, the studio became known for its fast-paced, low-cost productions and films of “social and political relevance.” This approach cultivated a distinctive brand that resonated with audiences of the time, often reflecting the grittier realities of American life.

The studio’s filmography under Warner is a testament to this strategic direction. Mervyn LeRoy “responded by pioneering the gangster film” with classics like “Little Caesar (1931)” and the powerful social commentary of “I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932).” William Wellman directed James Cagney to stardom in “The Public Enemy (1931).” Later, the studio produced wartime propaganda and romance with “Casablanca (1942),” exemplifying how director Michael Curtiz made “the most of inexpensive sets” and screenwriters completed “the sharp, literate script while the film was being shot.” Jack Warner was a master of making every dollar count.

4. **William Fox (Twentieth Century-Fox)**William Fox, the head of Twentieth Century-Fox, made a bold, yet ultimately disastrous, gamble that epitomized the risks inherent in the rapidly evolving film industry of the late 1920s. His studio heavily invested “on new sound equipment and a large theater chain” just before the onset of the Great Depression, a timing that proved catastrophically unfortunate for his leadership.

This aggressive expansion, fueled by heavy borrowing, left Twentieth Century-Fox incredibly vulnerable when the economic shocks hit. The financial burden was compounded by legal battles over the rights to the Fox sound system, which became “entangled in a legal battle.” Consequently, the “payments on the studio’s immense debt overwhelmed its income,” pushing the company to the brink.

The immense pressure led to a corporate restructuring that ultimately “removed Fox” from his position as studio head. It was a harsh lesson in the realities of power and finance within the studio system – even founders could be ousted when the bottom line suffered. His ambitious, albeit ill-timed, decisions serve as a cautionary tale of the period’s volatile business landscape.

Remarkably, the studio “survived on a narrow margin” after Fox’s departure, a testament to the underlying infrastructure and the resilience of the system itself. Though William Fox’s personal leadership ended in financial disarray and removal, the entity he founded managed to navigate the crisis, eventually finding its commercial mainstay in the infectious charm of child star Shirley Temple, ensuring its continuation as a major player, albeit under new guidance.

5. **Carl Laemmle (Universal)**Did you know that one of Hollywood’s original moguls, Carl Laemmle, was once an industry leader who had to sell his empire? As the founder and patriarch of Universal, Laemmle guided his studio through the roaring twenties, building a reputation that placed it among the industry’s vanguard. However, even the most established leaders weren’t immune to the seismic shifts of the Great Depression, which forced difficult decisions upon even the most powerful.

In 1929, Laemmle made a bold move, turning over Universal’s reins to his twenty-one-year-old son, Carl Jr. This youthful leadership sparked a period of audacious creativity. Under the younger Laemmle’s supervision, Universal produced the provocative anti-war film *All Quiet on the Western Front* (1930) and then, quite innovatively, broke new ground in the horror genre with iconic films like Bela Lugosi’s *Dracula* (1931) and Boris Karloff’s *Frankenstein* (1931). These films weren’t just hits; they defined monster movies for generations.

However, even groundbreaking artistic endeavors can fall victim to bad timing. The Laemmles’ creative thrusts unfortunately coincided with the leanest years of the Depression, when audience numbers dwindled. Universal soon faced a severe fiscal crisis, unable to sustain the momentum. By 1936, the financial pressures became insurmountable, and Carl Laemmle was forced to sell his interests in the studio he had founded, a poignant end to a foundational era for the family.

Yet, Universal, much like other studios struggling through the Depression, eventually found its footing again. It clawed its way back to solvency by focusing on B-pictures, serials, and harnessing the star power of teen sensation Deanna Durbin. By the 1940s, the studio had achieved a modest prosperity, proving that even after its visionary founder’s exit, the underlying structure of the studio system could endure and adapt, a true testament to the resilience of Hollywood.

6. **Cecil B. DeMille (Paramount)**Imagine a filmmaker whose name became synonymous with spectacle and who remained a commercial and critical powerhouse for decades. That was Cecil B. DeMille, a veteran producer-director whose influence extended far beyond the traditional studio executive role. While Paramount Pictures, his home studio, struggled financially through the 1930s, DeMille was one of those skillful directors who consistently delivered superior films that helped keep the studio afloat.

DeMille’s genius lay in his ability to craft grand historical dramas that captivated audiences and offered a powerful escape from the realities of the Depression. He possessed an almost unparalleled knack for blending epic storytelling with lavish productions. This consistent delivery of high-quality, commercially successful films made him a truly indispensable asset, a master craftsman whose vision directly translated into box-office gold for Paramount.

Consider the sheer scope and enduring appeal of his work during this challenging period. Films like *Cleopatra* (1934), starring the legendary Claudette Colbert, and *Union Pacific* (1939), an epic tale of railroad construction, showcased his distinctive flair. These weren’t just movies; they were events, meticulously planned and executed, demonstrating how a singular artistic vision could profoundly impact a studio’s fortunes, even when the broader financial picture was bleak. DeMille’s commercial success was a vital lifeline for Paramount during its most trying years.

7. **Howard Hughes (RKO)**And then there’s Howard Hughes, a name that conjures images of eccentric genius and disruptive power. His arrival at RKO Radio Pictures, long considered the financially shakiest of the “Big Five,” in May 1948, marked a pivotal moment, not just for the struggling studio but for the entire Hollywood system. At a time when the U.S. Supreme Court had just outlawed block booking through the landmark Paramount case, Hughes saw an opportunity to redefine the rules.

While the other Big Five studios dug in for a long legal battle against the court’s antitrust ruling, Hughes, recognizing that RKO controlled the fewest theaters, made a shocking move. He signaled his willingness to the federal government to agree to a consent decree, effectively obliging RKO to break up its movie business into two separate entities: RKO Pictures Corporation and RKO Theatres Corporation. This decision to proactively concede to “divorcement”—the complete separation of production/distribution from exhibition—was a true game-changer.

Hughes’s gambit, formally sealed with his agreement on November 8, 1948, became the “death knell for the Golden Age of Hollywood.” His willingness to break ranks terminally undermined the arguments of other studios who claimed such separations were unfeasible. Paramount soon followed suit, and the domino effect he initiated ultimately led to the demise of vertical integration, irrevocably altering the structure of the film industry forever.

However, while Hughes’s actions hastened the end of the studio system, his disruptive leadership did little to save RKO itself. Coupled with the rising tide of television drawing audiences away, the studio continued to falter. By 1957, RKO’s main facilities were sold to Desilu, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz’s production company, and by 1959, the once-mighty studio abandoned the movie business entirely. Hughes’s legacy remains a fascinating contradiction: a master of power who, in breaking the system, also inadvertently contributed to the downfall of the very studio he sought to control.

The stories of these eleven studio bosses and influential figures paint a vivid picture of Hollywood’s Golden Age—a period defined by both autocratic control and remarkable innovation. From the paternalistic might of Louis B. Mayer to the strategic defiance of Howard Hughes, these individuals were not just executives; they were architects, dream-weavers, and financial tightrope walkers, each leaving an indelible mark on an industry that, for all its power, notoriety, and contributions to American popular culture, ultimately underwent a profound transformation. Their reigns, often turbulent and always fascinating, remind us that even the most formidable empires are shaped, challenged, and ultimately redefined by the singular wills of those who stand at their helm. The golden age may have faded, but the echoes of their power continue to resonate in every flickering frame of cinema history.