The concept of a ‘cult’ is as old as human society itself, yet its definition has been a shapeshifter, morphing with the intentions of whoever uses it. What once denoted conventional religious devotion has, over centuries, become a term loaded with pejorative connotations, sparking alarm and controversy. From secretive ancient rites integrated into civic life to modern groups accused of brainwashing and violence, the narrative around ‘cults’ is a complex tapestry of faith, fear, and evolving societal understanding.

In our journey through this intricate landscape, we will uncover how these groups are perceived, categorized, and often misunderstood. We’ll delve into the academic attempts to define them, the historical shifts in their status, and the dramatic narratives that have cemented certain images in the public consciousness. Prepare to explore the fascinating evolution of what we call a ‘cult,’ a term that tells us as much about our own anxieties and values as it does about the groups it describes.

This exploration isn’t just about identifying what might be deemed ‘deviant’; it’s about understanding the sociological currents, political pressures, and deeply personal experiences that shape these movements. It’s a look back at ‘The Great Vanishing’ – not of clear-cut definitions, but of certainty in belief, and often, tragically, of individuals caught in the crosscurrents of intense devotion and societal apprehension.

1. **The Etymological Odyssey of ‘Cult’: From Sacred Rites to Scorned Groups**The word ‘cult’ embarks on a fascinating journey from its Latin root ‘cultus,’ meaning worship, to its modern, often derogatory, usage. In its older, non-pejorative sense, a cult simply referred to a set of religious devotional practices conventional within a given culture, frequently associated with a particular figure or place, and often involving collective participation in rites of religion. The imperial cult of ancient Rome, for example, was deeply integrated into the dominant political system, dedicated to the worship of deceased emperors and their deified family members.

This historical understanding stands in stark contrast to the common perception today. A derived sense of ‘excessive devotion’ emerged in the 19th century, gradually transforming the term into a pejorative label. Today, ‘cult’ is generally applied to groups exhibiting unusual, often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or to those showing intense, often perceived as unhealthy, devotion to a particular person, object, or goal.

Sociologist Susannah Crockford aptly describes the word as a ‘shapeshifter,’ its meaning fluid and dependent on the user’s intentions. As an analytical term, it resists rigorous definition, yet it carries ‘considerable cultural legitimacy’ in popular discourse. This semantic morphing highlights a central tension: between scholarly efforts to neutrally classify new religious movements and the widespread use of ‘cult’ to cast aspersion on a group’s validity or legitimacy. The term’s evolution reflects shifting societal norms and anxieties, underscoring the need for careful consideration when employing a word so heavily laden with historical and emotional baggage.

2. **Charting the Religious Landscape: Weber, Troeltsch, and Becker’s Groundbreaking Typologies**The academic study of religious groups, including those often labeled as ‘cults,’ gained significant traction in the 1930s, largely building upon the foundational work of pioneering sociologists. Max Weber, a pivotal theorist, laid groundwork with his concepts of charismatic authority and his crucial distinction between churches and sects. His insights provided early frameworks for understanding how religious movements organize and exert influence over their adherents, creating a more objective lens for study.

Building on Weber’s initial ideas, German theologian Ernst Troeltsch further elaborated on the church-sect division. Troeltsch introduced an additional ‘mystical’ categorization, acknowledging more personal or individual religious experiences that didn’t neatly fit into the larger, institutionalized ‘church’ or the smaller, breakaway ‘sect.’ This expanded typology began to capture the diverse organizational and experiential forms that religious life could take, highlighting its complexity.

American sociologist Howard P. Becker then refined Troeltsch’s model, bisecting the categories into ‘ecclesia’ and ‘denomination’ (from ‘church’), and ‘sect’ and ‘cult’ (from ‘sect’). In Becker’s formulation, a ‘cult’ referred to small religious groups characterized by a lack of formal organization and a strong emphasis on the private nature of personal beliefs. This definition highlighted their emergent, often spontaneous, nature, distinguishing them from more structured sects that typically arose from schisms within larger religions. These early typologies were instrumental in moving the discussion of religious groups beyond purely theological or judgmental terms, attempting to create a more objective, sociological understanding.

3. **Beyond Brainwashing: The Rise and Fall of a Controversial Theory**The 1970s marked a peak for the anti-cult movement, fueled by a compelling, yet ultimately flawed, theory: ‘brainwashing.’ This concept posited that individuals who joined cults were not making autonomous choices but were, in fact, victims whose free will had been systematically stripped away through manipulative ‘mind control’ techniques. This narrative resonated deeply with public anxieties, particularly as new and unconventional religious groups gained traction, triggering widespread alarm among families and communities.

A high-profile case that significantly bolstered this belief was the trial of Patty Hearst. Kidnapped by leftist radicals in 1974, Hearst subsequently participated in crimes, which her defense argued was a result of brainwashing. This case, extensively covered by the media, solidified the idea that individuals could be coerced into adopting beliefs and actions against their will, lending a veneer of legitimacy to the brainwashing theory in the popular imagination.

This theory provided a justification for a controversial practice known as ‘forcible deprogramming.’ This often involved the kidnapping and holding of cult members, sometimes against their will, until a deprogrammer judged that they were no longer ‘in the thrall of the cult.’ The goal was to ‘break’ the alleged brainwashing and return individuals to their former selves, as perceived by their families and deprogrammers, leading to a number of legal challenges.

However, the legal and academic scrutiny that followed began to dismantle the brainwashing theory. Many deprogrammed individuals sued both the cults they had left and, crucially, their deprogrammers, claiming kidnapping and abusive coercion. Extensive research by medical professionals and organizations like the American Psychological Association in the 1980s and ’90s concluded that accusations of brainwashing and coercive persuasion lacked factual basis, often finding methodological flaws or insufficient data in supporting studies. The practice of forcible deprogramming largely ceased after a former cult member won a lawsuit against his deprogrammer in 1995, marking a significant turning point in the understanding of how individuals join and leave these groups.

4. **From Cult to NRM: Academia’s Quest for a Neutral Term**As the ‘brainwashing’ theory began to unravel and scholarly research provided a more nuanced understanding of new religious groups, academics found themselves grappling with the problematic nature of the term ‘cult.’ The word had accumulated such a strong negative connotation that it was increasingly used as a pejorative, casting aspersion on the validity of any group it described, irrespective of their actual practices or impact. This inherent bias made it difficult to conduct objective sociological study.

By the end of the 1970s, many scholars began to abandon the term ‘cult’ in favor of more neutral language. The most popular and widely adopted alternative became ‘new religious movement’ (NRM). Other proposed terms included ’emergent religion,’ ‘alternative religious movement,’ or ‘marginal religious movement,’ all aimed at creating a lexicon that dissociated these groups from the damaging implications of the word ‘cult’ and fostered greater academic rigor.

The shift to NRM was a deliberate attempt to remove the pejorative baggage and allow for a more objective, academic study of these phenomena. Scholars recognized that the term ‘cult’ often served to dehumanize individuals within these groups, and its use, particularly by media and governments, had sometimes been a significant factor in escalating conflicts, such as the Waco siege. It was seen as an effort to bring scholarly rigor to a field often dominated by sensationalism and moral panic.

Despite academia’s efforts, the secular anti-cult movement largely viewed ‘new religious movement’ as a euphemism, arguing that it diluted the implied harms associated with ‘cults.’ This ongoing contention highlights the deep-seated cultural legitimacy and emotional resonance that the term ‘cult’ retains in popular discourse. Yet, for researchers, the move to NRM represented a critical step toward a more balanced and respectful approach to understanding the diverse landscape of religious and spiritual expression, allowing for a more accurate and less biased analysis.

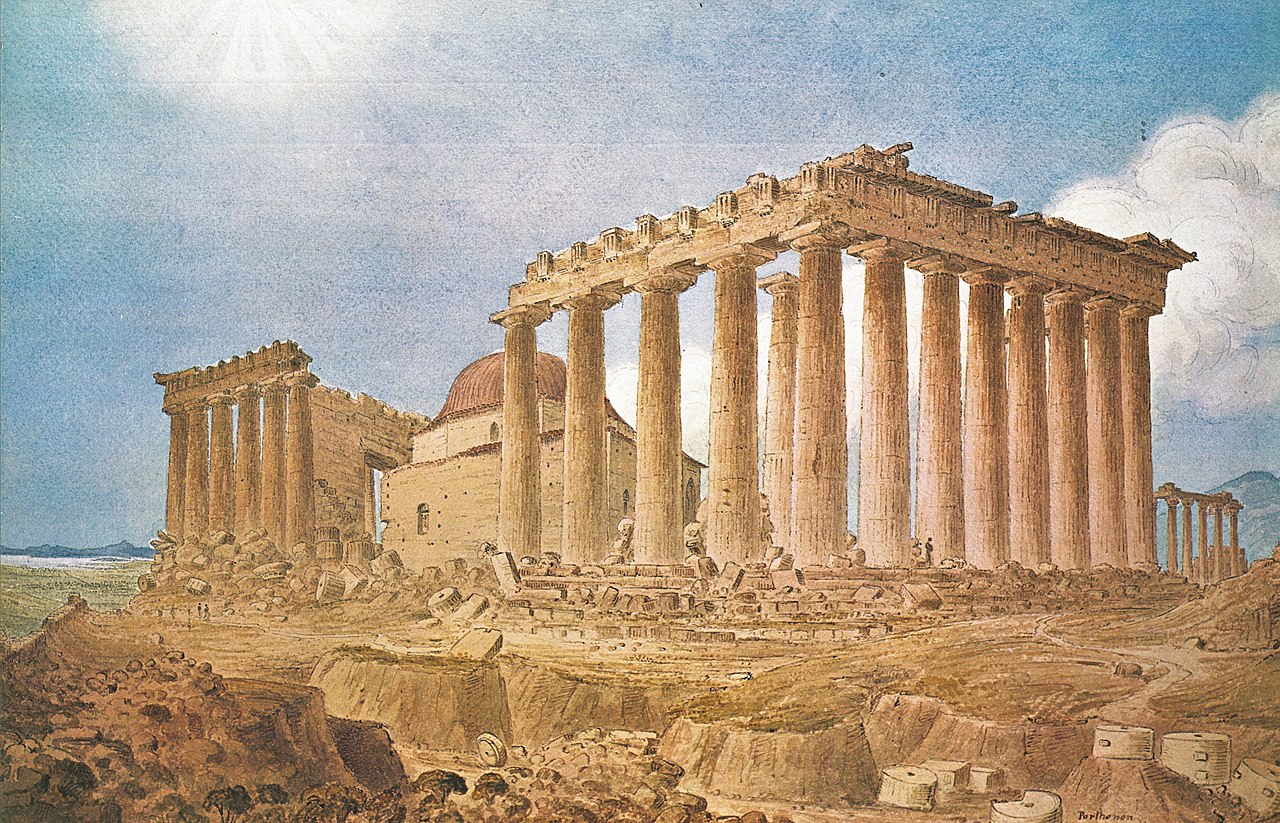

5. **Ancient Reverence: The Integrated Cults of Isis and the Roman Emperors**While the modern understanding of ‘cult’ often evokes images of isolated, manipulative groups, ancient history presents a dramatically different picture. In the classical Mediterranean world, ‘mystery cults’ were common, representing small groups whose elite members underwent initiation into secret rituals for a particular deity. Far from existing in tension with the broader society, many of these Roman cults were deeply integrated into the civic and social order of their time.

A vivid example is the cult of Isis. This Egyptian deity’s worship expanded significantly beyond Egypt, reaching both Greek and Roman territories, and finding a prominent place even in cities like Pompeii. There, one of the most lavishly decorated temples was dedicated to the cult of Isis, underscoring its acceptance and prestige. An inscription at the site records that the individual who funded the temple’s refurbishment was rewarded with a position as a town councilor, a clear indicator of the strong interconnection between this mystery cult and the city’s established civic authority.

Even more pervasive was the imperial cult, a prominent Roman practice dedicated to the worship of deceased and deified Roman emperors and their deified family members. This form of devotion actively reinforced the power of the dominant political system. Most, if not all, of pre-Christian Roman society had some degree of membership in this cult, highlighting how religious devotion could be seamlessly woven into the fabric of political and social life, serving to bolster state authority rather than challenge it. These ancient examples demonstrate that the term ‘cult,’ in its original historical sense, carried no negative connotations. Instead, it described forms of intense devotion that were often conventional, publicly accepted, and even integral to maintaining social cohesion and political stability. Understanding this historical context is crucial for appreciating the vast semantic shift the word has undergone and the differing roles such groups have played throughout history.

6. **The People’s Temple: A Socialist Experiment’s Tragic End in Jonestown**The People’s Temple, founded in 1955 by American Christian pastor Jim Jones, stands as a chilling paradigm of what the anti-cult movement would later label a ‘destructive cult.’ Initially known as the ‘People’s Temple Christian (Apostolic) Church,’ its trajectory took a dark and ultimately catastrophic turn, culminating in the collective suicide of over 900 members in the Guyanese tropical jungle in November 1978. This event etched the group into public memory as the epitome of an extremist cult.

Jones, who expressed fervent admiration for figures like Mao Zedong and Lenin, and was described by survivors as primarily a socialist and an atheist, sought to establish a socialist ideal society. In 1977, he led nearly a thousand members to Guyana, where they established ‘Jonestown,’ an agricultural commune. This supposed utopia, however, quickly devolved into a communist autocracy, characterized by brutal control and isolation, as members’ passports and property were confiscated, armed guards patrolled day and night, and contact with the outside world was strictly forbidden.

Jones employed ‘Maoist techniques’ for indoctrination, utilizing high-volume loudspeakers to broadcast messages accusing external ‘fascist’ forces in the US of trying to destroy their socialist experiment. Members were subjected to 12-hour workdays, followed by ‘criticism and self-criticism’ sessions, a practice explicitly learned from Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party. Those who failed tasks or expressed doubt faced severe punishments, including public humiliation like head-shaving or wearing yellow hats, beatings, abuse, and even execution, echoing practices of China’s Cultural Revolution.

The tragic climax arrived after Jones orchestrated multiple ‘collective suicide drills’ to test loyalty. Following his order to murder visiting US Congressman Leo Ryan, Jones gathered all commune members for a final ‘revolutionary suicide.’ As people died, they were heard murmuring, “Let us die for the revolution. Use our death, expose this racist and fascist society. In this great revolutionary suicide, how beautiful it is to die!” The Jonestown massacre remains a stark and haunting warning about the dangers of unchecked charismatic leadership, ideological extremism, and the profound vulnerability of isolated communities, forever impacting the public’s perception of such groups.

7. **Doomsday Visions: When Prophecy Fails and What We Learn From It**The phenomenon of ‘doomsday cults’ offers a unique lens into the psychology of belief, particularly concerning apocalyptic and millenarian visions. These groups are defined by their conviction in an impending catastrophe, sometimes predicting it, and in more extreme cases, attempting to actively bring it about. The study of such groups provides invaluable insights into human responses to existential anxieties and the dynamics of collective conviction, illuminating how prophecy shapes belief.

One of the most pivotal studies in this area was conducted in the 1950s by social psychologist Leon Festinger and his colleagues. They meticulously observed members of a small UFO religion known as the Seekers, documenting their conversations both before and after a key event: a failed prophecy from their charismatic leader. The Seekers believed that extraterrestrials would rescue them from a cataclysmic flood that was prophesied to destroy the world on a specific date.

When the predicted doomsday failed to materialize, a critical moment of cognitive dissonance arose. Instead of abandoning their beliefs, many members of the Seekers, as documented in Festinger’s influential book ‘When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World,’ intensified their conviction and proselytizing efforts. They reinterpreted the event, believing their faith had averted the disaster, thereby reinforcing, rather than disproving, their core beliefs in the face of contradictory evidence.

This study illuminated a crucial psychological mechanism: when deeply held beliefs are challenged by contradictory evidence, individuals may rationalize or even strengthen those beliefs rather than abandon them. It demonstrated that for those who have invested significantly in a worldview, especially after repeatedly failing to find meaning in mainstream movements, a cataclysmic vision can become deeply entrenched. The lessons from ‘When Prophecy Fails’ continue to inform our understanding of group psychology, the resilience of belief, and the complex ways in which individuals navigate the disconfirmation of their most profound expectations, providing enduring insights into the human condition.

Navigating the history of ‘cults’ reveals a curious truth: definition shifts with perception and political winds. In the modern era, lines between legitimate faith and ‘deviant’ blur, often dictated by power. This section delves into contemporary cult phenomena, examining political influence, global suppression, and enduring questions of faith and control. From ancient transformations to modern controversies, prepare for another deep dive into the fascinating world of cults.

8. **The Cross and the Crown: How Christianity Transformed from Persecuted Cult to Empire’s Religion**

Imagine being branded an enemy, your faith a dangerous ‘cult,’ your members thrown to the lions. This was reality for early Christians in Rome. Their growing numbers and refusal to worship imperial deities made them a perceived threat, leading to brutal suppression under emperors like Nero, who labeled Christianity a ‘cult.’ For three centuries, followers endured criminalization and persecution.

History offers few turnarounds so dramatic. The 4th century brought a seismic shift with Emperor Constantine’s conversion. What was once a despised ‘cult’ gained legal recognition, moving from shadows into imperial favor. This profound embrace catapulted Christianity to unprecedented prominence, reshaping Rome’s religious landscape.

Indeed, Christianity, once the victim of the ‘cult’ label, ultimately became the official state religion. With this dominance, the tables turned. Other religious practices were branded ‘heresies’ or ‘pagan cults’ by Christian authorities. Theodosius II’s 435 CE decree banned pagan rituals, mandating temple conversions. This arc vividly demonstrates how a group’s definition and acceptance are linked to political power.

9. **The Unofficial ‘Cult’ of Saints: Devotion Within Mainstream Faiths**When ‘cult’ pops up, our minds often jump to fringe groups, but intense devotion can thrive within mainstream faiths. The older, non-pejorative meaning of ‘cult’ simply referred to fervent devotion to a figure or idea. It reminds us spiritual ardor isn’t always something to fear or marginalize.

Consider the Roman Catholic Church. Within its venerable structure, ‘cults’ of devotion to the Virgin Mary and numerous saints have flourished for centuries. Far from rebellious, these movements gained immense influence, shaping theology and inspiring countless artistic masterpieces. They became integral to Christian culture, showcasing the power of focused reverence.

Even today, individuals intensely worshipping specific saints are sometimes identified, academically, as members of that saint’s ‘cult.’ This usage carries no nefarious implication or deviation from orthodoxy. It underscores a powerful, personal connection to a revered figure. It highlights the human need for spiritual exemplars, showing how ‘cult’ in its truest etymological form describes deep devotional practices within established faiths.

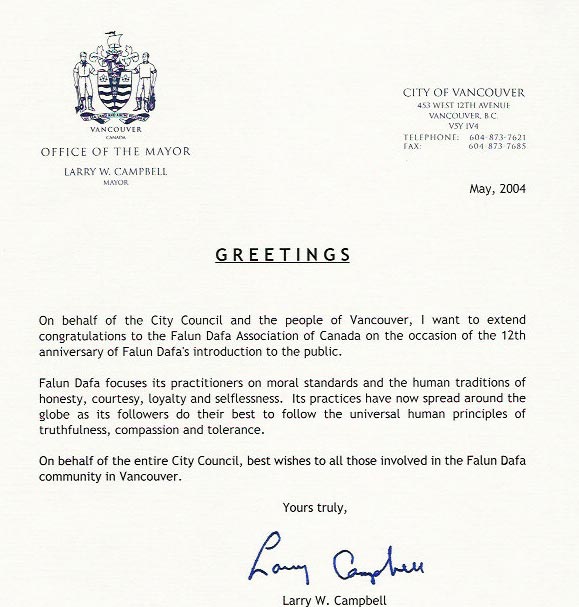

10. **Falun Gong in the Crosshairs: A Qigong Movement’s Global Struggle for Recognition**In the late 20th century, Falun Gong, a qigong practice, experienced explosive growth across mainland China and over 70 countries. The Chinese government estimated 70 to over 100 million practitioners by the late 1990s. Initially overseen by the State Sports Commission, Falun Gong emphasized moral elevation and physical health, capturing the CCP’s attention.

However, this popularity led to a shift under Jiang Zemin, culminating in a nationwide crackdown in July 1999. International bodies, including the U.S. House and Taiwan’s Congress, cited extensive CCP disinformation campaigns and questioned state-orchestrated events like the ‘Tiananmen self-immolation incident.’ Amnesty International documented ongoing threats, torture, and censorship against practitioners, highlighting severe human rights abuses.

Despite suppression, debate emerged over Falun Gong’s classification. Scholars like David Ownby and journalist Ian Johnson argue it doesn’t fit common cult definitions, suggesting the CCP used Western anti-cult legitimacy. While a 1999 Supreme People’s Court notice mentioned Falun Gong, subsequent Public Security Ministry lists notably excluded it. This legal ambiguity, coupled with active suppression, underscores politically driven ‘cult’ designations in China.

11. **Quannengshen’s Dark Shadow: The McDonald’s Murder and a Controversial Group**Emerging from the ‘Shouters’ movement in 1989, Quannengshen, or All-Powerful Spirit, was founded by Zhao Weishan. This offshoot of the Protestant Local Church movement, despite claiming a ‘female Christ,’ is reportedly controlled by Zhao. Quannengshen established a significant international presence, with branches spanning major global cities, demonstrating its controversial nature.

The group gained widespread and tragically notorious public attention in 2014 due to the gruesome ‘5.28 Zhaoyuan McDonald’s Murder Case’ in Shandong. A woman was beaten to death inside a fast-food restaurant for refusing to provide her phone number. This horrific incident shocked the nation, cementing the group’s image as violent and dangerous.

Legal consequences for the perpetrators were swift and severe. On October 11, 2014, the Yantai Intermediate People’s Court delivered its first-instance verdict: Zhang Fan and Zhang Lidong received death sentences for intentional homicide. Lü Yingchun received a life sentence, and two others faced long prison terms. The judgment cited intentional homicide and ‘utilizing a cult organization to undermine law enforcement,’ showcasing state resolve.

12. **The Curious Case of China’s Family Churches: Labeled ‘Cult’ for Non-Compliance**In China, the Communist Party targets independent Christian ‘family churches’ operating outside state-sanctioned bodies like the Three-Self Patriotic Church. Some are labeled ‘cults,’ with local authorities even declaring non-affiliated churches as inherently ‘cultish.’ This policy effectively criminalizes independent religious practice, irrespective of its theological content.

These administrative labels lead to severe repercussions. Individuals face arrest and prosecution for activities considered standard elsewhere. For instance, Li Guangqiang and others were apprehended for transporting ‘Recovery Version Bibles.’ Initially charged with ‘utilizing a cult organization to undermine law enforcement,’ they were later sentenced for ‘illegal business operations,’ revealing systematic legal maneuvers.

Reports confirm the CCP’s view of family churches as political threats, aiming to abolish non-Three-Self congregations. Propaganda, like posters branding family churches as ‘cult organizations impersonating religious names,’ is widespread. China’s Anti-Cult Association’s list alarmingly includes 15 Christian-linked groups among 20. This trend raises concerns about criminalization under Article 300, underscoring deep political motivations.

13. **When the State Itself is Questioned: Is the CCP the ‘Biggest Cult’ of All?**Here’s a provocative question: Can a state, especially one aggressively suppressing ‘cults,’ exhibit cult-like characteristics itself? This unsettling perspective often arises from critics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Historian Zhang Lifan, for instance, described the ‘Communist Party regime as a sect,’ seeing religions as ideological rivals, with tightened control stemming from fear of losing social command.

The irony became palpable with a 2014 New York Times article by Murong Xuecun. It highlighted CCTV’s announcement of ‘six characteristics of cult organizations,’ including personal worship and restriction of freedom. Murong Xuecun noted these traits mirrored communist China. Public response was immediate: netizens ironically applied characteristics to the CCP, suggesting they ‘finally know which one is the biggest cult,’ reflecting widespread disillusionment.

Reinforcing this, CCP historian Sima Lu characterized the Party’s rule from its Yan’an period as ‘witch cult-like.’ He cited deification of leaders, absolute power over life/death, suppression of independent thought (‘members as tools’), and imposition of ‘original sin’ to achieve ‘mental enslavement.’ This analysis disturbingly parallels destructive cult mechanisms within a totalitarian political system.

14. **The American Anomaly: Religious Freedom’s Shield Against ‘Cult’ Labels**Governments globally vary wildly in their approach to new religious organizations, often disagreeing on what constitutes a ‘cult.’ Some, like France and Belgium, readily accept ‘brainwashing’ theories, while others, such as Sweden and Italy, maintain a more neutral stance. This international divergence highlights the challenge of defining acceptable religious practice, yet the United States offers a starkly different model.

The American anomaly is rooted in its First Amendment, which robustly protects religious freedom, setting a high bar for state intervention. Unlike many nations where unconventional beliefs trigger ‘cult’ labels and suppression, the US prioritizes individual rights to practice chosen religions. Criminalization targets groups demonstrably involved in activities that harm others, not just unorthodox beliefs.

Under this protective shield, practices like intense persuasion for donations, ‘brainwashing’ (a subjective term), or unconventional medical approaches are constitutionally protected, unless accompanied by concrete criminal actions. The US system demands proof of actual harm, rather than questioning a group’s ‘deviance’ or legitimacy. It’s a testament to individual liberty, fostering a unique sanctuary for diverse spiritual expressions.

The journey through the world of cults, from ancient reverence to modern controversies, reveals a landscape far more complex and nuanced than simple labels suggest. It’s a story of shifting definitions, political leverage, psychological vulnerabilities, and the enduring human quest for meaning and belonging. Whether integrated into civic life or on society’s fringes, these groups and our perceptions reflect societies’ anxieties, values, and power structures. Understanding them demands curiosity, critical thinking, and a willingness to look beyond sensationalism to profound forces at play.

.jpg)