The deep-sea world, an expanse of crushing pressure and perpetual darkness, remains one of Earth’s last great frontiers. For a select few, the allure of exploring its abyssal depths, particularly the famed wreckage of the RMS Titanic, proved irresistible. It was this ambition that drew five individuals aboard the submersible Titan, operated by OceanGate Expeditions, for a journey to the ocean floor that would tragically end in a “catastrophic implosion,” claiming all lives on board. The grim discovery of debris, including the tail cone of the vessel, approximately 1,600 feet from the bow of the Titanic, marked the somber conclusion of a frantic multinational search. This incident has cast a stark light on the frontiers of extreme tourism, prompting a close examination of the submersible’s design, operational philosophy, and the inherent risks of venturing into one of the planet’s most unforgiving environments. The Titan, a vessel that proudly defied conventional design, became a focal point of global attention, revealing a story woven with elements of groundbreaking engineering, unconventional choices, and the ever-present specter of the deep ocean’s immense power. Its unique characteristics, from a control system resembling a video game controller to a minimalist interior, underscore a narrative that has resonated far beyond the confines of deep-sea exploration, touching on questions of safety, innovation, and human endeavor.

The final descent of the Titan submersible began early on a Sunday, a venture intended to culminate in an awe-inspiring view of the Titanic’s resting place, nearly 13,000 feet beneath the North Atlantic waves. Less than two hours into its journey, specifically at 11:47 a.m. Sunday, contact with its mothership, the Polar Prince, was inexplicably lost. This critical silence triggered an extensive search-and-rescue operation that captured worldwide attention, with state, federal, and international resources mobilized in a desperate race against the submersible’s estimated 96-hour life support capacity. The vessel, designed for expeditions lasting approximately 10 to 11 hours, vanished into the vast, cold expanse of the ocean.

Among those aboard were Stockton Rush, the CEO and founder of OceanGate Expeditions, British businessman Hamish Harding, French diver Paul-Henri Nargeolet, and the Pakistani father-son duo, Shahzada Dawood and Suleman Dawood. Their aspirations to witness the historic shipwreck firsthand were cut short by the unforeseen disaster. The discovery of the debris field by a remotely operated vehicle on Thursday confirmed the most feared outcome, drawing a definitive and tragic close to the search for the Titan and its occupants. The very ocean they sought to explore ultimately became their final, silent resting place, a stark reminder of the immense forces at play in the deep.

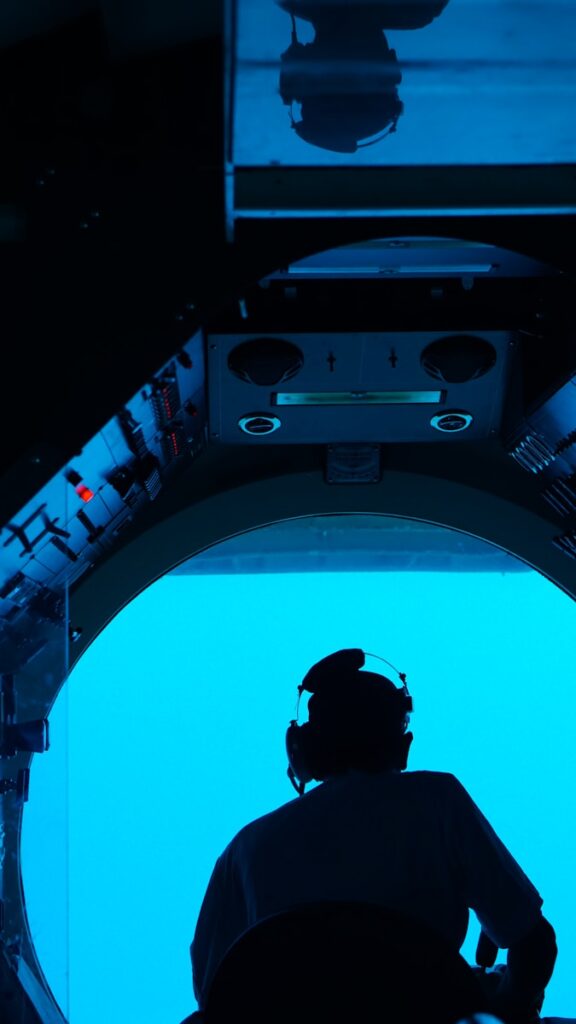

Inside the Titan, the environment was as unconventional as its external design philosophy. Described as being roughly the size of a minivan, the vessel offered limited space for its five occupants. Passengers were required to sit cross-legged on the floor, as there were no traditional seats within its cramped confines. The sole means of external viewing was a single porthole, offering a focused, albeit restricted, glimpse into the abyssal surroundings. This minimalist approach extended to other amenities, or the distinct lack thereof. For instance, the submersible was equipped with only one toilet, an essential facility reduced to a simple water bottle for convenience during multi-hour dives.

Such Spartan conditions were part of a deliberate design choice by OceanGate, aiming to streamline operations and prioritize functionality over traditional comforts often associated with exploratory vessels. David Pogue, a CBS correspondent who had previously taken a trip on the Titan, noted its sparse interior and the custom of crew members to remove their shoes inside. This interior design, while perhaps jarring to an outsider, was integral to the operational ethos of the Titan, reflecting a vision for deep-sea exploration that diverged significantly from established norms. It encapsulated a philosophy where every element was seemingly pared down to its most fundamental purpose.

Perhaps the most striking and widely discussed aspect of the Titan’s operational interface was its navigation system. The submersible was piloted not by a complex array of levers and buttons, but by what was essentially a video game controller, specifically a modified Logitech gamepad. This choice, intended to simplify the operational experience, was central to OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush’s vision. Rush, during a 2022 interview with David Pogue, famously asserted, “This is not your grandfather’s submersible. We only have one button – that’s it. It should be like an elevator; it shouldn’t take a lot of skill.” This philosophy underscored a commitment to accessibility and ease of use, even in the highly specialized field of deep-sea exploration.

Beyond the gaming controller, other “off-the-shelf components” were integrated into the Titan’s construction. For instance, one of its interior lights was reportedly purchased from CamperWorld, a recreational vehicle company. While these choices led Pogue to describe the vessel as having a “MacGyver jerry-riggedness,” Rush vehemently disagreed, emphasizing that his team collaborated with reputable entities such as Boeing, NASA, and the University of Washington to ensure the vessel’s capability of withstanding extreme deep-sea pressures. Rush confidently stated that “Everything else can fail. Your thrusters can go, your lights can go, you’re still going to be safe.” This assertion highlighted his belief in the core structural integrity of the submersible, designed to protect its occupants even amidst system failures.

OceanGate’s website further elaborated on this engineering approach, noting that the Titan combined “groundbreaking engineering and off-the-shelf technology,” with the latter chosen to “streamline the construction” and enhance ease of operation. Aaron Newman, an investor in OceanGate and a past passenger on the Titan, confirmed the use of the game controller for wireless control, but also noted the existence of an internal hard-wire system for propeller control should the remote fail. This layered approach to control was seemingly designed to offer redundancy. The craft also operated under strict orders to maintain distance from the Titanic wreckage, a precautionary measure aimed at preventing entanglement or trapping in the debris, indicating a recognition of the hazards posed by the wreck itself.

The Titan, classified as a submersible rather than a submarine, possessed limited power reserves, necessitating the presence of a support ship like the Polar Prince on the surface for both launching and recovery. Unlike submarines that can remain submerged for months, the Titan’s typical operational window for a trip to the Titanic wreck was approximately 10 to 11 hours. Communication during dives relied solely on text messages exchanged with the mother ship, as conventional GPS, Wi-Fi, and radio links are non-functional in the deep ocean environment. According to OceanGate Expeditions’ archived website, the submersible was mandated to communicate every 15 minutes, a protocol designed to maintain a consistent link with the surface and monitor its progress.

Despite the stated safety features and design intentions, previous expeditions with the Titan had encountered a series of notable incidents and challenges that hinted at the inherent unpredictability of deep-sea ventures. Mike Reiss, who had completed four 10-hour dives with OceanGate, including one to the Titanic, recounted that his submersible lost contact with the host ship on “every dive,” suggesting that communication lapses were “baked into the system.” On one particular tour, a group diving in the Titan became disoriented, getting lost for two and a half hours and failing to locate the shipwreck. These incidents, while ultimately resolved, underscored the persistent navigational and communication difficulties faced in such extreme depths.

Furthermore, OceanGate’s expeditions were not immune to external factors. Several dives were canceled due to adverse weather conditions, and at least one dive was aborted because multiple floats detached from the Titan. Such occurrences indicated a sensitivity to environmental conditions and equipment integrity that could rapidly alter expedition plans. The contractual nature of these voyages also revealed an explicit acknowledgment of severe risks. Mike Reiss noted signing “a waiver that mentions death three times on the first page,” a detail that soberly underscored the potential grave outcomes. He candidly admitted, “It is always in the back of your head that this is dangerous, and any small problem will turn into a major catastrophe.”

The deep ocean environment presents a formidable array of challenges, rendering it a realm of extreme peril. As David Gallo, a senior adviser for Strategic Initiatives, RMS Titanic, aptly put it, “It’s like a visit to another planet, it’s not what people think it is. It is a sunless, forever cold environment – high pressure.” Temperatures in the abyssal depths hover just above freezing, necessitating internal heating systems within the submersible. Aaron Newman described the intense cold experienced at the bottom, recalling that passengers “had layered up. You had wool hats on and were doing everything to stay warm at the bottom.” Beyond temperature, the confined space within the Titan raised concerns about air quality. John “Danny” Olivas, a retired astronaut with experience in underwater habitats, highlighted the potential hazards of carbon dioxide generation by five people in a small, confined vessel, warning it could create “a poisonous environment for the crew members.”

Despite these daunting realities, those who embarked on these expeditions often did so with a deep understanding and acceptance of the inherent risks. Aaron Newman characterized the passengers not merely as “tourists” but as “people who lived on the edge and loved what they were doing.” He added that in the face of adversity, such individuals are “calm and thinking this through and doing what they can to stay alive.” The cost of these eight-day tours, around $250,000 per client, also suggested a clientele seeking not just an adventure, but a unique, high-stakes experience at the very edge of human exploration. The ability to “steer and navigate the sub for a while,” as Mike Reiss noted, might have also contributed to a sense of empowerment among the passengers, even as the ultimate control lay with the submersible’s design and its human operators.

The catastrophic implosion of the Titan submersible offers a profound, somber lesson in the ongoing quest to push the boundaries of human endeavor. It serves as a stark reminder that while innovation and a pioneering spirit can unlock new realms of experience, the inherent forces of nature, particularly in environments as extreme as the deep ocean, demand an uncompromising commitment to safety and engineering rigor. The unique blend of conventional and unconventional technologies within the Titan, from aerospace collaborations to commercial off-the-shelf components and a video game controller, represents a bold, yet ultimately tragic, experiment in deep-sea accessibility. As the world reflects on the lives lost and the circumstances that led to this disaster, the focus inevitably turns to how future explorations into the planet’s most remote reaches can balance audacious ambition with an unwavering respect for the perilous unknown. The legacy of the Titan, and the courageous individuals aboard will undoubtedly shape the future dialogue on the delicate interplay between human curiosity and the formidable power of the natural world.