Ever wonder what really happens behind the glitz and glamour when celebrities take their disputes to court? We’ve all seen the headlines, the dramatic accusations, and the promise of a legal showdown. But oftentimes, these high-profile battles end not with a bang, but with a dismissal, leaving fans and followers scratching their heads.

It turns out, the legal arena is a whole different ballgame than the court of public opinion. While social media might be buzzing with theories, judges operate strictly on facts, legal precedents, and whether claims meet very specific definitions. This means that even the most sensational allegations can get thrown out if they don’t tick all the right legal boxes.

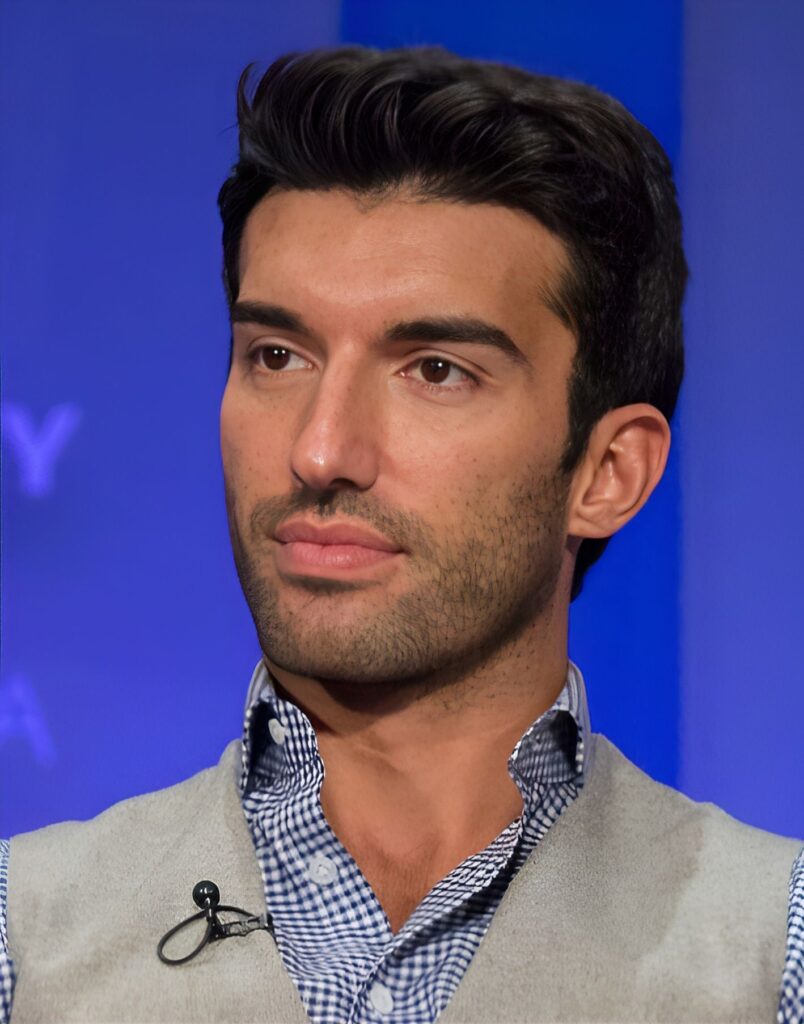

Take the recent legal saga involving actor and director Justin Baldoni and his ‘It Ends With Us’ costar Blake Lively. What started with Lively’s claims of ual harassment and retaliation escalated into a massive $400 million countersuit from Baldoni against Lively, Ryan Reynolds, and The New York Times, alleging defamation and extortion. But guess what? A judge just threw out Baldoni’s entire countersuit! So, what went down? Let’s dive into the legal nitty-gritty and uncover the core reasons why celebrity lawsuits like this one often get dismissed.

1. **When Allegations Are Protected: The “Privilege” Defense**

One of the biggest hurdles for defamation claims, especially in a legal battle that’s already public, is something called ‘privilege.’ This isn’t about being famous; it’s a legal shield for statements made in specific, protected contexts. In the case of Justin Baldoni’s defamation claim against Blake Lively, the court highlighted that allegations made in a lawsuit are often exempt from libel claims.

U.S. District Court Judge Lewis Liman explicitly ruled that Baldoni couldn’t sue Lively for defamation over claims she made in her legal complaint because such allegations are ‘exempt from libel claims.’ This is a critical legal concept. It means that what you say in an official court document, even if it’s disputed, generally can’t be used as the basis for a defamation lawsuit against you, because these statements are considered ‘privileged.’ The legal system encourages parties to fully and freely present their case within the confines of a lawsuit without immediate fear of a retaliatory defamation suit.

This ‘litigation privilege’ is quite robust. The court found that Lively’s statements, made in her civil rights complaint, were indeed privileged and, as such, ‘could not support a claim for defamation.’ It also didn’t matter if the complaint was shared with the press *before* it was officially filed, as long as there was a good faith intention to file it. In California, where some of these events transpired, a party doesn’t have to wait until a document is filed before providing it to the press, as long as they intend in good faith to file it.

Furthermore, the judge pointed out that even if Lively presented a version of events that was ‘deceptively favorable (or even untrue),’ it didn’t impact this litigation privilege. This underscores the power of this legal protection; it’s designed to protect the integrity of the legal process itself, ensuring parties can pursue their claims without being immediately entangled in a new, separate defamation battle over the initial allegations. It’s a way to keep the focus on the primary legal dispute.

Adding another layer of protection, since 2023, California specifically recognizes a privilege for statements made by a victim ‘regarding an incident of ual assault, harassment, or discrimination.’ This applies if the victim ‘has, or at any time had, a reasonable basis to file a complaint’ about such incidents. This means Lively’s initial complaint, alleging sexual harassment, was doubly protected under state law, making Baldoni’s defamation claim against her nearly impossible to sustain.

2. **Proving Malice: Why Public Figures Face a Higher Bar**

When a celebrity tries to sue someone for defamation, especially if they are a ‘public figure,’ they face a much higher legal standard. It’s not enough to simply say something false and damaging was said; you have to prove that the statement was made with ‘actual malice.’ This is a huge hurdle and a common reason why defamation claims, particularly in the glare of the public eye, often get dismissed.

What exactly is ‘actual malice’? The court defines it as either ‘actual knowledge of falsehood or reckless disregard for the truth.’ So, if you’re a public figure, you have to show that the person who made the statement either knew it was false when they said it, or they acted with a careless disregard for whether it was true or not. This isn’t about whether someone *should* have known; it’s about their state of mind when they made the statement. It’s a tough standard to meet, and it exists to protect open discourse, even when it involves public figures.

In Baldoni’s lawsuit, he also alleged defamation against Ryan Reynolds and publicist Leslie Sloane. However, the court found that Baldoni’s claims didn’t meet this ‘actual malice’ standard. The allegations, as presented, ‘showed Reynolds and Sloane repeated Lively’s version of events in her complaint and did not indicate any reason why they would have doubted Lively’s version of events.’ Essentially, if they believed Lively’s allegations to be true, they couldn’t be accused of ‘actual malice.’

The judge further elaborated on this, stating that the claims ‘did not support a defamation claim because there was no allegation of actual malice (i.e. knowledge of falsehood or reckless disregard of the truth).’ The court specifically noted that the ‘allegations showed Reynolds and Sloane made the statements believing they were true.’ For example, the court pointed to allegations that Reynolds reacted aggressively towards Baldoni on multiple occasions and sought to harm him ‘based on facts Reynolds genuinely believed were true.’ Similarly, Sloane was found to have ‘repeated what Lively alleged in her complaint, and available facts supported her statements.’ Without proving that Reynolds or Sloane knowingly lied or recklessly disregarded the truth, the defamation claim against them couldn’t stand.

3. **Consistency is Key: Statements Backed by Official Complaints**

Another significant factor in the dismissal of defamation claims, particularly concerning those made by third parties like friends or family, is whether their statements are consistent with existing official legal allegations. If someone repeats or interprets allegations that are already part of a formal legal complaint, and they have no reason to doubt their veracity, those statements are often protected from defamation claims.

In Baldoni’s case, he accused Ryan Reynolds of falsely labeling him a ‘ual predator.’ However, the judge found that this specific statement was ‘also consistent with Blake’s allegations in her complaint.’ Because Reynolds’s comment aligned with Lively’s existing legal claims, and the court found that Reynolds ‘had no reason to believe they were untrue,’ that comment could not form the basis of a defamation claim. This is a crucial distinction: simply repeating or echoing allegations already made in a privileged legal document, especially when you believe them to be true, isn’t enough to constitute defamation against you.

The court emphasized that the available information to Reynolds supported his belief in Lively’s version of events. This means that if an individual hears a claim made in a legal setting, and their subsequent statements are in line with those claims without any clear evidence they *knew* the claims were false, they are generally protected. It reinforces the idea that individuals are often not liable for repeating or believing claims that have been formally presented in a court of law, unless there’s an obvious and provable intent to deceive or a reckless disregard for the truth.

This principle ties directly into the ‘actual malice’ standard for public figures we discussed earlier. If a public figure’s statement is consistent with information that they genuinely believe to be true, especially if that information comes from an official legal source, it becomes incredibly difficult to prove the ‘knowledge of falsehood’ or ‘reckless disregard for the truth’ required for a successful defamation claim. It prevents a cascade of lawsuits from simply repeating allegations already being litigated.

4. **Fair Game: Why Media Reporting on Lawsuits is Often Protected**

It’s not just celebrities and their inner circles who are protected; media outlets also have significant legal defenses when reporting on official legal proceedings. In an age where news breaks instantly, the press often plays a crucial role in informing the public about high-profile legal battles. But what happens when their reporting draws the ire of one of the parties involved? Generally, if their reporting accurately reflects legal documents, they’re in the clear.

Justin Baldoni’s countersuit wasn’t just against Lively and Reynolds; it also targeted The New York Times, accusing the newspaper of defamation. Baldoni alleged that the Times ‘cherrypicked certain text messages and emails to frame him as the bad guy’ in an article that reported on Lively’s ual harassment allegations. However, the court unequivocally dismissed this defamation lawsuit against the Times, ruling that their reporting was fair and protected.

The judge’s decision was clear: ‘the Times reviewed the available evidence and reported, perhaps in a dramatized manner, what it believed to have happened.’ Crucially, the court found that ‘the Times’ reporting closely tracked Blake’s version of events in her complaint.’ This means that as long as the media accurately conveys what is stated in official legal documents, even if those statements are controversial or presented with a certain narrative flair, they are generally protected. The Times was seen as reporting on a matter of public importance, and the law is designed to protect that kind of journalism.

The court even highlighted that the Times ‘had no obvious motive to favor Lively’s version of events.’ This lack of discernible bias further strengthened their defense against the defamation claim. The New York Times spokesperson, Charlie Stadtlander, echoed this sentiment, stating they were ‘grateful to the court for seeing the lawsuit for what it was: a meritless attempt to stifle honest reporting.’ This outcome underscores a fundamental principle of journalistic freedom: the press has a right to report on judicial proceedings and legal complaints without fear of being sued for defamation, as long as their reporting is accurate and fair. It’s a vital safeguard for transparent public discourse, even when it involves intense celebrity drama.

Alright, so we’ve peeled back a few layers of the legal onion, uncovering why some celebrity defamation claims don’t make it past the first hurdle. But wait, there’s more! The legal landscape of Hollywood disputes is full of twists and turns, and some claims that sound pretty dramatic in the headlines often crumble under the cold, hard definitions of the law. Let’s dive into the next set of reasons why even the juiciest allegations can get thrown out of court.

It’s all about meeting very specific legal criteria. Judges aren’t swayed by dramatic narratives; they’re looking for whether a claim fits the precise, often narrow, definitions set forth in legal precedents. This distinction between public perception and legal reality is crucial, especially when we talk about accusations like ‘extortion’ or ‘breach of contract’ in a high-stakes environment like a movie set.

5. **When “Civil Extortion” Claims Don’t Add Up**

Ever heard someone threaten to “extort” another person and thought, “Wow, that sounds intense!” In the world of celebrity disputes, accusations of extortion can really make headlines. But legally, what constitutes ‘extortion’ is much more specific than what you might imagine, and often, claims of civil extortion in high-profile cases fall surprisingly short.

Under California law, for a civil extortion claim to stick, a plaintiff needs to prove that a defendant took money or property from them *under threat*, and the plaintiff then seeks to have that money or property returned. It’s a pretty clear-cut definition: there has to be an exchange of something valuable, compelled by a threat. Without that tangible transfer, it’s incredibly difficult to prove extortion in a court of law.

Justin Baldoni’s legal team alleged a civil extortion claim against Blake Lively, Ryan Reynolds, and publicist Leslie Sloane. They claimed that Lively, with assistance from Reynolds and Sloane, essentially “hijacked” the film ‘It Ends With Us’ from Baldoni and his company, Wayfarer Studios. The core of their argument was that Lively threatened to refuse to promote the film and even publicly attack Baldoni and Wayfarer if her demands for increased control over and credit for the film weren’t met. Sounds like a tense negotiation, right?

However, the court saw things differently. U.S. District Court Judge Lewis Liman ruled that Lively’s alleged actions didn’t actually qualify as civil extortion under California law. Instead, the judge found that what Baldoni’s team described as threats were, in legal terms, merely “hard bargaining or renegotiation of working conditions.” This is a super important distinction: pushing hard for better terms or more control in a business negotiation, even if it feels aggressive, isn’t inherently illegal. It’s often just how Hollywood, and business in general, operates.

Crucially, the court also pointed out another major missing piece for Baldoni’s extortion claim: he didn’t demonstrate any “monetary damage.” Remember that legal definition? Extortion requires the actual transfer of money or property that the plaintiff then wants back. Baldoni’s claims outlined alleged threats and efforts to seize control, but they didn’t show that any money or property was actually taken from him under duress. Without that tangible loss and an attempt to recover it, the claim simply didn’t meet the legal requirements. The court even went as far as to reject Baldoni’s request to amend this claim, stating it would be “futile,” meaning there was no way to fix it with additional allegations. It highlights just how precise legal definitions are, and how dramatically they can differ from everyday interpretations of words.

6. **The Elusive “Implied Contract”: Why Specificity Matters**

When you hear “contract,” you probably think of a thick document, signed by everyone, full of tiny print. But sometimes, legal claims arise from what are called “implied contracts,” agreements that aren’t explicitly written down but are understood through the actions and conduct of the parties involved. Sounds a bit nebulous, right? That’s exactly why these claims can be incredibly tough to prove, and often lead to dismissals if not supported by precise details.

In California, if you want to claim a “breach of implied contract,” you’ve got to bring some specifics to the table. A plaintiff must clearly allege two things: first, the existence of very specific contractual obligations that were understood to be in place, and second, that there was interference with the plaintiff’s ability to perform that contract or a failure to cooperate as implied by the agreement. Without detailing these specific obligations, it’s hard for a judge to understand what was supposedly agreed upon, let alone what was breached.

Justin Baldoni’s lawsuit included an allegation that Blake Lively breached an “implied actor contract.” His legal team claimed that Lively’s alleged actions — including making threats, seizing creative control over the film, and thereby depriving Baldoni and Wayfarer Studios of “the opportunity to produce, edit, and market a film as contemplated by the contract” — constituted a breach of this unwritten agreement. It paints a picture of a co-star overstepping boundaries and undermining the original understanding of how the film would be made.

However, the court found Baldoni’s allegations to be “conclusory.” What does that mean in plain English? It means the claims were too general, lacking the nitty-gritty details a court needs to assess whether a contract, even an implied one, truly existed and was violated. Judge Liman specifically pointed out that Baldoni’s team “did not allege any terms of the alleged contract, the parties to the alleged contract, or when the contract was made.” You can’t just say there was an implied agreement; you need to spell out what those implied terms *actually were*, who was bound by them, and when this invisible contract came into being.

Because of this lack of specificity, the court ruled that Baldoni’s claims didn’t show any concrete “contractual provision with which Lively allegedly interfered.” It’s like trying to argue someone broke a rule when you can’t even state what the rule was. The claim for breach of implied contract was dismissed. Interestingly, unlike the extortion claim, the court did allow Baldoni’s side an opportunity to amend this part of the lawsuit. The judge noted that, potentially, Baldoni’s team *could* allege specific details about Lively’s contract with Wayfarer, including if there was a provision about exercising her rights in a “reasonable manner.” This highlights that while the initial claim was too vague, the door was left ajar for a more detailed, fact-based re-filing, underscoring the legal system’s demand for explicit terms, even when arguing for an implicit agreement.

7. **”Tortious Interference”: High Bar for Evidentiary Requirements**

Beyond direct accusations like defamation or breach of contract, some lawsuits involve claims of “tortious interference.” This fancy legal term basically means someone purposely messed with a business relationship or contract that you had, or were about to have, with a third party. It’s a way to claim damages when someone else’s actions unfairly disrupt your economic opportunities. However, proving tortious interference is often a steep uphill battle, demanding a high bar for evidentiary requirements.

There are usually a couple of flavors of tortious interference claims: tortious interference with contractual relations (meaning an existing contract was messed with) and tortious interference with prospective economic advantage (meaning a future business opportunity was derailed). Both require proving not just that interference happened, but that it was *intentional* and caused actual *damage*. And that intent, especially in the murky waters of Hollywood dealings, can be incredibly difficult to concretely demonstrate to a court.

In the case of Justin Baldoni’s countersuit, his team asserted multiple alternative claims for tortious interference. One significant allegation was that Blake Lively and Ryan Reynolds intentionally interfered with a contract Baldoni had with WME, a major talent agency. The claim suggested that Lively and Reynolds made threats specifically to induce WME to “drop” Baldoni as a client. Imagine the impact of losing your agency in Hollywood—that’s a huge blow to your career and economic prospects.

Another claim revolved around Lively and Reynolds allegedly interfering with Baldoni’s “prospective economic relations,” meaning future deals, projects, or partnerships that were on the horizon. This type of claim is particularly challenging because it requires proving that a future relationship *would have* materialized had it not been for the alleged interference. It’s not just about a lost deal, but about proving the certainty of a deal that never happened because of someone else’s actions.

The very nature of these claims, as the court’s prior dismissals imply, often hinges on demonstrating clear, undeniable evidence of intent and direct causation. Just like with defamation, where “actual malice” must be proven for public figures, tortious interference claims require strong proof that the defendants *knowingly and intentionally* acted to disrupt specific economic relationships, and that their actions *directly* led to the claimed harm. Without concrete evidence of such deliberate interference, and a clear causal link to specific financial losses, these claims are often seen as speculative or based on indirect circumstances, making them ripe for dismissal. The legal system isn’t interested in a “he said, she said” about motives; it wants documented proof of targeted, damaging actions.

So, as we’ve seen, whether it’s battling over alleged extortion that doesn’t meet the legal definition, vague “implied contracts” that lack specific terms, or “tortious interference” claims that struggle to provide concrete evidence of intent and causation, the path to winning a celebrity lawsuit is incredibly narrow. It’s a constant reminder that the dramatic headlines we read are often just the tip of a very complex legal iceberg. Judges meticulously dissect every claim, looking for adherence to strict legal standards, not just compelling narratives. It turns out, in the court of law, celebrity status and public opinion take a backseat to rigorous legal principles and cold, hard facts. And that, my friends, is why so many high-profile battles end with a dismissive shrug from the bench, rather than a blockbuster verdict.