The bedrock of any functioning society is its justice system, and at its very core stands the judge. These pivotal figures, entrusted with the profound responsibility of upholding the rule of law, navigate the intricate pathways of legal disputes, ensuring fairness and consistency within court proceedings. Their decisions, rooted in a deep understanding of legal principles and careful assessment of facts, resonate with significant governmental power, yet are subject to a robust system of checks and balances.

Understanding the multifaceted role of a judge requires a comprehensive look into their duties, the varying legal traditions they operate within, and the meticulous processes by which they are appointed. It also involves an appreciation for the rich global tapestry of customs and forms of address that underscore the solemnity of their office. From their fundamental definition to the nuanced protocols of courtroom decorum, the position of a judge is one of immense consequence and continuous evolution.

At its most fundamental, a judge is defined as a person who presides over court proceedings, whether acting alone or as part of a larger judicial panel. Their ultimate task is to settle legal disputes in a final and publicly lawful manner, always in agreement with substantial partialities. In performing this role, judges are expected to conduct trials with unwavering impartiality, typically within an open court, ensuring that justice is not only done but also seen to be done.

Within the adversarial legal system, characteristic of jurisdictions like the United States and England, the judge functions primarily as an impartial referee. Their central responsibility in such a system is to ensure correct procedure is followed, while the prosecution and the defense present their respective cases to a jury. Here, the jury, often selected from common citizens, serves as the main factfinder, with the judge finalizing the sentencing upon their verdict.

However, in smaller cases, judges in adversarial systems possess the authority to issue summary judgments, thereby bypassing the need for a full jury trial. This flexibility allows for the efficient resolution of less complex matters, demonstrating a practical aspect of judicial power that balances thoroughness with expediency. The judge’s acumen in these instances is critical to swift and equitable outcomes.

Conversely, the inquisitorial system, prevalent in continental Europe, presents a distinct judicial landscape. In this model, there is no jury; instead, the judge assumes the comprehensive role of the main factfinder, directly engaging in the presiding, judging, and sentencing. The expectation within this framework is that the judge will apply the law directly, embodying the French expression, “Le juge est la bouche de la loi” (“The judge is the mouth of the law”).

Beyond their central role in adjudication, judges in inquisitorial systems may even conduct investigations, functioning as an examining magistrate. This broader scope of responsibility highlights a fundamental difference in judicial philosophy, where the judge takes a more active, investigative stance to uncover facts and apply legal principles. Such systems demand a profound and hands-on engagement with every aspect of a case.

Regardless of the specific legal system, judges wield significant governmental power. They are empowered to issue orders to police, military, or judicial officials for actions such as searches, arrests, imprisonments, garnishments, detentions, seizures, and deportations. This authority underscores their crucial position within the executive functions of the state.

Yet, this immense power is not unchecked. Judges are also tasked with supervising trial procedures to ensure consistency and impartiality, actively working to prevent arbitrariness in legal outcomes. A critical mechanism for accountability is the oversight provided by higher courts, including courts of appeal and supreme courts, which review decisions and ensure adherence to legal standards.

The legal ecosystem typically features three main legally trained court officials: the judge, the prosecutor, and the defense attorney. While judges may preside alone in smaller cases, criminal, family, and other significant matters often necessitate a panel of judges. Some civil law systems even incorporate lay judges, who, unlike professional judges, are not legally trained but serve as volunteers and may be politically appointed.

Professional judges require a robust legal education, often culminating in a Juris Doctor degree in the United States. Furthermore, significant professional experience is a prerequisite, with judges frequently appointed from the ranks of seasoned attorneys. Their demanding occupation necessitates exceptional skills in logical reasoning, analysis, and decision-making to research and process extensive documents, witness testimonies, and complex case materials.

Beyond analytical prowess, excellent writing skills are indispensable for judges, given the finality and authority of the documents they produce. Interpersonal skills and dispute resolution abilities are equally vital, as judges constantly interact with various individuals and must skillfully manage conflicts. Upholding a good moral character, free from any history of crime, is a non-negotiable requirement for those who embody justice.

Judicial appointments are typically made by the head of state, though in some jurisdictions, judges are elected through political processes. The principle of impartiality is paramount for the rule of law, leading many jurisdictions to appoint judges for life, thereby insulating them from executive removal. This long tenure is intended to foster independence and ensure decisions are made free from political pressures.

However, in non-democratic systems, the appointment of judges can be highly politicized. In such contexts, judges may receive explicit instructions on how to rule and face removal if their conduct fails to align with the political leadership’s expectations. This stark contrast highlights the importance of judicial independence in truly democratic societies.

Professional judges often enjoy a high salary, reflecting the gravity and demands of their position. In the United States, the median annual salary for judges stands at $101,690, with federal judges earning substantially more, typically between $208,000 and $267,000 per annum. This compensation acknowledges the extensive expertise and profound responsibilities vested in the role.

The debate surrounding age and retirement for judges, particularly in the United States, is a complex one. Federal judges in the U.S. are appointed “for good behavior,” meaning they typically serve until death, voluntary retirement, or impeachment. The passing of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in office in 2020 and the suspension of Pauline Newman in 2023 reignited discussions about mandatory retirement ages for federal judges.

However, any change to this system would require a constitutional amendment, making it an unlikely prospect in the near future. States, conversely, possess greater flexibility in establishing mandatory retirement ages for their court judges, a flexibility affirmed by the Supreme Court of the United States in its 1991 decision, Gregory v. Ashcroft. As of 2015, thirty-three states and the District of Columbia have such provisions, with retirement ages typically ranging from 70 to 75, though Vermont stands out with an age as high as 90.

A 2020 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research yielded significant insights into this matter, finding positive effects on the performance of state Supreme Courts that implement mandatory retirement ages for judges. The authors of the study advocated for the adoption of such policies across all federal and state judges, while emphasizing that individual authorities should retain the prerogative to determine the specific age.

Examining gender representation within the judiciary reveals intriguing global patterns. In many civil law countries across Europe, women constitute the majority of judges at the first instance, with Slovenia, Serbia, Latvia, Luxembourg, Greece, and Hungary reporting that women make up more than 70% of their first-instance judges. This represents a significant and positive shift towards gender balance in these nations.

Conversely, in common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Malta, and the United States, the situation is reversed, with over 70% of first-instance judges being men. This disparity highlights ongoing challenges in achieving equitable representation in certain legal traditions. The data underscores the diverse pathways and progress in gender parity across different judicial systems worldwide.

Further up the judicial hierarchy, women remain underrepresented in the supreme courts of the United States and member states of the European Union. A notable exception is Romania, where women comprise over 80% of the judges of the High Court of Cassation and Justice, showcasing a remarkable level of representation at the highest judicial level within that nation.

Judicial office is often accompanied by a variety of traditions and symbols that underscore its gravitas. Gavels, the ceremonial hammers, are widely used by judges in many countries, to the extent that the gavel itself has become an iconic symbol of a judge. These symbols contribute to the solemnity and authority of court proceedings.

In many parts of the world, judges wear long robes, frequently in black or red, and preside from an elevated platform known as the bench. American judges commonly wear black robes, and while they possess ceremonial gavels, their primary means of maintaining courtroom decorum are their court deputies or bailiffs and the power of contempt of court. Interestingly, in some parts of the Western United States, like California, judges did not always wear robes and instead wore everyday clothing, a practice that has evolved.

Today, some members of state supreme courts, such as the Maryland Supreme Court, wear distinct dress, reflecting a blend of tradition and regional identity. In Italy and Portugal, both judges and lawyers adhere to the custom of wearing particular black robes, creating a uniform visual presence within the legal profession. Further afield, in Oman, the judge is distinguished by a long stripe in red, green, or white, while attorneys wear the customary black gown.

The tradition of judges wearing wigs, particularly in the Commonwealth of Nations, is another distinctive aspect of judicial attire. The long wig often associated with judges is now typically reserved for highly ceremonial occasions, a relic of standard attire from previous centuries. In daily court proceedings, a shorter wig, known as a Bench Wig, resembling but not identical to a barrister’s wig, would be worn.

However, this particular tradition is gradually being phased out in Britain, particularly in non-criminal courts, indicating a move towards more contemporary forms of judicial dress. In Portugal and the former Portuguese Empire, judges historically carried a staff, red for ordinary judges and white for those from outside the main judicial hierarchy, a unique symbol of their authority.

The forms of address for judges vary significantly across continents and cultures, reflecting deep-seated historical and linguistic traditions. In Hong Kong, where proceedings are conducted in both English and Hong Kong Cantonese, judges retain many English traditions, including the wearing of wigs and robes. In the lower courts, magistrates are addressed as “Your Worship,” and district court judges as “Your Honour.”

For the superior courts of record, including the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal and the High Court, judges are addressed as “My Lord” or “My Lady” and referred to as “Your Lordship” or “Your Ladyship,” in keeping with English tradition. In written communication, specific post-nominal letters are used, such as PJ for a permanent judge of the Court of Final Appeal, JA for a justice of appeal, and J for a judge of the Court of First Instance. Masters of the High Court are simply addressed as “Master.”

When trials are conducted in Chinese, judges in Hong Kong were historically addressed as “Fat Goon Dai Yan” (meaning ‘Judge, your lordship’) before the transfer of sovereignty from the United Kingdom to China. Since 1997, the address has shifted to “Fat Goon Gok Ha” (meaning ‘Judge, your honour’), or simply “Fat Goon” (‘Judge’), indicating a subtle yet significant evolution in protocol.

In India, the tradition of addressing judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts as “Your Lordship” or “My Lord” and “Your Ladyship” or “My Lady” is a direct legacy of English colonial influence. However, this practice has faced modern resistance, with the Bar Council of India adopting a resolution in April 2006 to allow lawyers to use “Your Honour” or “Honourable Court,” and “sir” or regional equivalents for subordinate courts, viewing the older terms as “relics of the colonial past.” Despite this, the resolution has largely remained on paper, though one judge of the Madras High Court, Justice K Chandru, took the unprecedented step in October 2009 of banning the use of “My Lord” and “Your Lordship” in his court.

In Israel, judges across all courts are addressed with the formal “Sir” or “Madam” (adoni/geverti), or “Your Honor” (kevodo/kevoda), typically followed by “haShofét,” meaning “the judge.” For instance, “Your Honor the Judge” would be rendered as “kevod haShofét.” In Malaysia, judges of subordinate courts are addressed as “Tuan” or “Puan” (Sir/Madam) or “Your Honour,” while superior court judges are addressed as “Yang Arif” (meaning ‘Learned One’) or “My Lord,” “My Lady,” and their respective Ladyship forms, particularly in English proceedings.

Pakistan maintains the tradition of “Your Lordship” or “My Lord” for Supreme Court and High Court judges, alongside “Your Ladyship” or “My Lady,” though this also faces religious objections. In lower courts, judges are addressed as “sir,” “madam,” or the Urdu equivalents “Janab” or “Judge Sahab.” Sri Lanka generally uses “Your Honour” for most judges, with the Chief Justice being addressed as “Your Lordship.” Judges of the Supreme Court and the Appeal Court are afforded the title “The Honourable.” In Vietnam, judges are addressed as “Quý tòa,” literally translating to “the Honorable Court.”

European traditions for addressing judges are equally diverse. In Bulgaria, the communist-era address of “drugarju” (comrade) was replaced after 1989 with “gospodín sŭdiya” (mister judge) or “gospožo sŭdiya” (madam judge). Finland presents a less formal approach, with no special form of address required beyond ordinary politeness, often using “herra/rouva puheenjohtaja” (Mr./Ms Chairman). While Finnish judges use gavels, they do not wear robes or cloaks in court.

In France, the presiding judge is addressed as “Monsieur le président” or “Madame le président,” while associated judges are “Monsieur l’Assesseur” or “Madame l’Assesseur.” Outside the courtroom, they are simply referred to as “Monsieur le juge” or “Madame le juge.” Germany employs “Herr Vorsitzender” or “Frau Vorsitzende” (Mister/Madam Chairman), or the formal “Hohes Gericht” (High Court). Hungary uses “tisztelt bíró úr” (Honourable Mister Judge) for men and “tisztelt bírónő” (Honourable Madam Judge) for women, or “tisztelt bíróság” (Honourable Court) for the body as a whole.

Ireland’s judicial address forms have also evolved. Judges of the Supreme Court, Court of Appeal, or High Court are officially titled “The Honourable Mr/Mrs/Ms/Miss Justice Surname” and informally referred to as “Mr/Mrs/Ms/Miss Justice Surname.” In court, they may be addressed by their titles, as “The Court,” or simply “Judge.” Circuit Court judges are titled “His/Her Honour Judge Surname” and addressed as “Judge,” a change from the pre-2006 “My Lord.” District Court judges are titled “Judge Surname” and addressed as “Judge,” moving away from “Your Worship” before 1991.

In Italy, the presiding judge is addressed as “Signor/Signora presidente della corte” (Sir/Madam president of the court) or “Vostro Onore” (Your Honour). The Netherlands employs specific written addresses: “edelachtbare” for judges in the Court of First Instance, “edelgrootachtbare” for justices in the Court of Appeal, and “edelhoogachtbare” for justices in the High Council (Supreme Court). Poland uses “Wysoki Sądzie” (High Court) for presiding judges during trials.

Portugal addresses presiding judges as “Meretíssimo Juiz” (Most Worthy Judge) for men or “Meretíssima Juíza” for women, or “Vossa Excelência” (Your Excellency) when not specifying gender. In Romania, judges are addressed as “Onorata Instanta” (Your Honor). In Russia, “Vasha Chest” (Your Honour) is used for criminal cases with a single judge, while “Honorable Court” is for civil, commercial, and criminal cases presided over by a panel.

Spain utilizes “Your Lordship” (Su Señoría) for magistrates of the Supreme Court, magistrates, and judges. In more formal settings, Supreme Court magistrates are “Your Most Excellent Lordship,” and lower court magistrates are “Your Most Illustrious Lordship.” Simple judges are always called “Your Lordship.” Sweden’s presiding judges are traditionally addressed as “Herr Ordförande” or “Fru Ordförande” (Mister/Madam Chairman).

The United Kingdom’s judicial addresses are intricate and steeped in tradition. In England and Wales, Supreme Court judges are Justices of the Supreme Court, addressed as “My Lord/Lady.” High Court and Court of Appeal judges are also addressed as “My Lord” or “My Lady” and referred to as “Your Lordship” or “Your Ladyship.” Lords of Appeal are formally “Lord Justice N” or “Lady Justice N” and in legal writing carry the post-nominal letters “LJ.” High Court Justices are referred to as “Mr./Mrs./Ms Justice N.” with the post-nominal “J” in legal writing.

Circuit judges and recorders are addressed as “Your Honour,” and magistrates are typically addressed as “Your Worship” or “Sir/Madam.” Scotland’s courts, including the Court of Session, High Court of Justiciary, and sheriff courts, also use “My Lord” or “My Lady,” with justices of the peace addressed as “Your Honour.” Northern Ireland’s system is similar, with county court judges addressed as “Your Honour” and district judges (magistrates’ court) as “Your Worship.”

In North America, Canadian judges may be directly addressed as “My Lord,” “My Lady,” “Your Honour,” or “Justice,” and are formally referred to in the third person as “The Honourable Mr. (or Madam) Justice ‘Forename Surname.'” Less formally, superior court judges are called “Justice ‘Surname’.” In Ontario, “Your Honour” is common for the Superior Court of Justice. French translations include “Monsieur le juge” and “Madame la juge.” “Judge” is generally used for anonymous positions or members of inferior courts, though Citizenship Judges are explicitly referred to as “Judge ‘Surname’.” Justices of the peace are “Your Worship,” and as of December 7, 2018, Ontario Court Masters are addressed as “Your Honour.

Across the United States, judges are commonly addressed as “Your Honor” or simply “Judge” when presiding over a court, with attorneys frequently opting for the latter. These varied forms of address reflect a global respect for the judicial office and the diverse cultural contexts in which justice is administered.

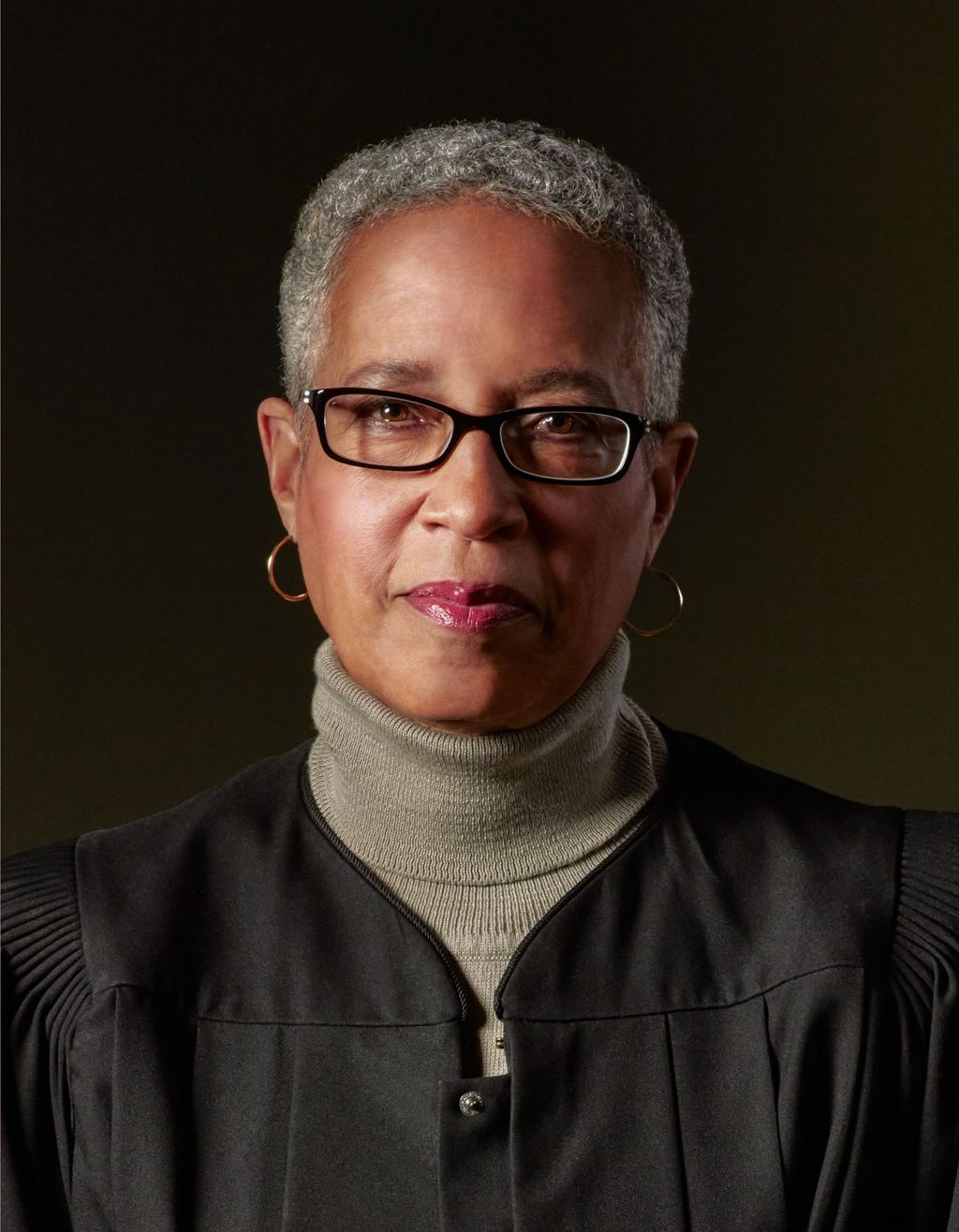

Providing a tangible illustration of this continuous process, Governor Gavin Newsom announced the appointment of 16 Superior Court Judges on June 18, 2025. These appointments, distributed across Los Angeles, Merced, Orange, San Diego, San Francisco, Santa Clara, San Joaquin, and Tulare Counties, underscore the ongoing commitment to bolstering the state’s judicial infrastructure. Each appointee brings a distinct professional background to their new role, filling vacancies created by retirements or other judicial advancements.

In Los Angeles County, six new judges were appointed. William Forman, formerly a Partner at Winston & Strawn, LLP and Scheper Kim & Harris, LLP, and a Deputy Federal Public Defender, fills the vacancy left by Judge James A. Kaddo. David Garcia, previously a Supervising Attorney at Inner City Law Center and a Senior Attorney at Southern California Edison Company, steps into the role vacated by Judge Daniel Feldstern. Sumako McCallum, a Court Commissioner and Senior Deputy County Counsel, takes the seat made available by Judge Anne Hwang’s appointment to the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California.

Alan Z. Yudkowsky, who served as a Court Commissioner and Principal at his own law offices, fills the vacancy created by the retirement of Judge Barbara M. Scheper. Melanie Chavira, a City Prosecutor at the Redondo Beach City Attorney’s Office and a Trial Advocacy Instructor, assumes the position vacated by Judge Mary Lou Villar. Lastly, Terrence Jones, Chief Trial Counsel at Cameron Jones and formerly an Assistant U.S. Attorney, fills the vacancy resulting from Judge Serena R. Murillo’s appointment to the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California. Notably, all these Los Angeles County appointees are registered Democrats, a consistent political affiliation among the new judicial cohort.

Moving to Merced County, Ashley Albertoni Sausser, an Attorney at Albertoni & Associates and previously in multiple roles at Fagalde, Albertoni & Flores, has been appointed to fill the vacancy left by Judge Shelly Seymour’s retirement. In Orange County, Randall Bethune, a Commissioner and Senior Deputy Public Defender, steps into the role vacated by the retirement of Judge James L. Waltz. Both Albertoni Sausser and Bethune are also registered Democrats.

San Diego County sees the appointment of Deborah Cumba, a Commissioner and Deputy Attorney at the California State Department of Transportation, who fills the vacancy created by the retirement of Judge Howard H. Shore. Cumba, like her fellow appointees, is a Democrat. In San Francisco County, John D. Echeverria, a Supervising Deputy Attorney General and Adjunct Professor, fills the vacancy from Judge Anne-Christine Massullo’s retirement. Dawn Payne, an Attorney in the Legal Services office of the Judicial Council of California, takes the seat left by Judge Kathleen A. Kelly’s retirement. Both San Francisco appointees are Democrats.

Santa Clara County receives three new judges. Jeffrey El-Hajj, a Research Attorney for the Sixth Appellate District Court of Appeal, fills the vacancy created by the retirement of Judge Peter H. Kirwan. Eunice Lee, a Deputy District Attorney for the Santa Clara County District Attorney’s Office, takes the seat vacated by Judge Vanessa Zecher’s retirement. Erik Johnson, a Commissioner and Solo Practitioner, fills the position left by Judge Carrie Zepeda-Madrid’s retirement. All three Santa Clara appointees are registered Democrats.

Finally, San Joaquin County welcomes Adam Ramirez, a Shareholder at Hakeem, Ellis, Marengo & Ramirez and an Adjunct Professor, who fills the vacancy created by the retirement of Judge Jose L. Alva. In Tulare County, Frank Ruiz, a Deputy County Counsel at the Kings County Counsel’s Office, takes the seat left by the retirement of Judge Brett R. Alldredge. Both Ramirez and Ruiz are also Democrats. Each of these newly appointed superior court judges will receive a compensation of $244,727 per annum, a standard figure for these significant public service roles.

The role of a judge, whether presiding over a local court or serving on the highest judicial panel, remains one of profound importance to the integrity and stability of society. They are not merely adjudicators of disputes but guardians of liberty, ensuring that the intricate machinery of the law operates with fairness, impartiality, and adherence to established principles. Their dedication ensures the pursuit of justice is not an abstract ideal but a tangible reality for all.

From the solemn rituals of court dress and formal address to the complex legal philosophies that shape their daily work, judges worldwide embody a commitment to legal order. The recent appointments in California serve as a timely reminder of the continuous effort to strengthen the judiciary, a process vital to the health of our democratic institutions. The enduring impact of judges lies in their unwavering commitment to the rule of law, guiding societies toward a more just and equitable future.