In the annals of Christian history, few figures command as much veneration and enduring influence as James. Not merely a singular individual, but a name deeply interwoven with pivotal narratives, James emerges from the foundational texts as a figure of immense spiritual gravity and practical wisdom. This exploration delves into the distinct yet interconnected legacies associated with this name, charting the compelling journey of James the Great, the Apostle, and then navigating the authoritative teachings encapsulated within the New Testament’s Book of James.

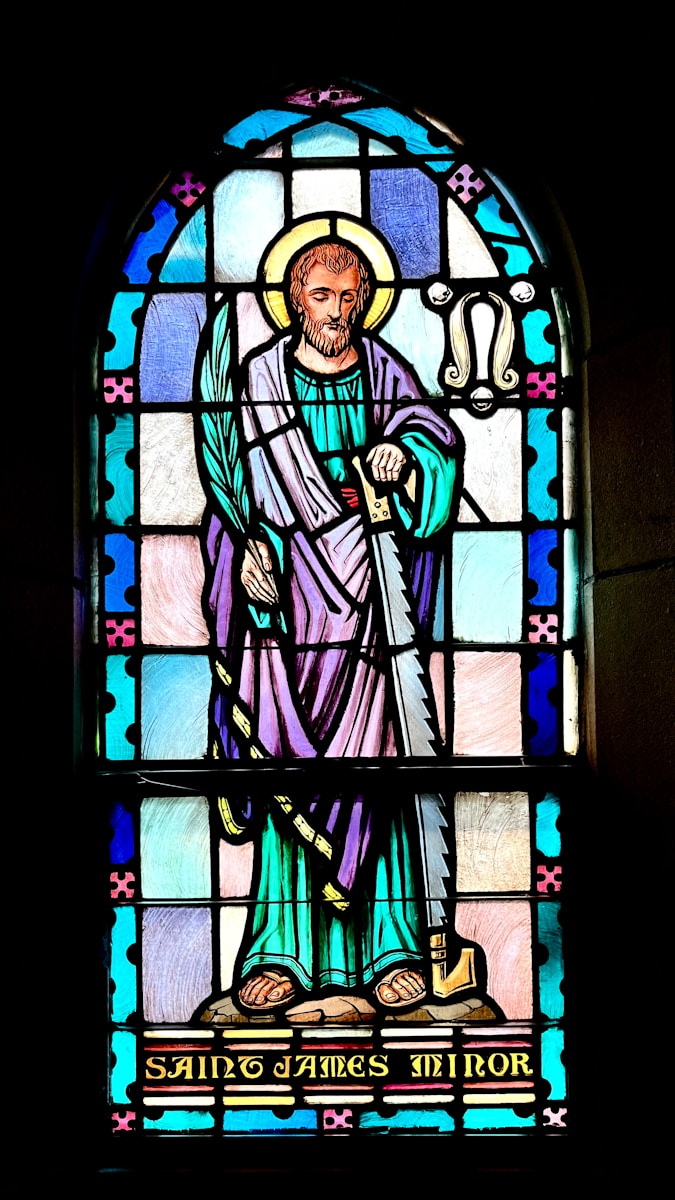

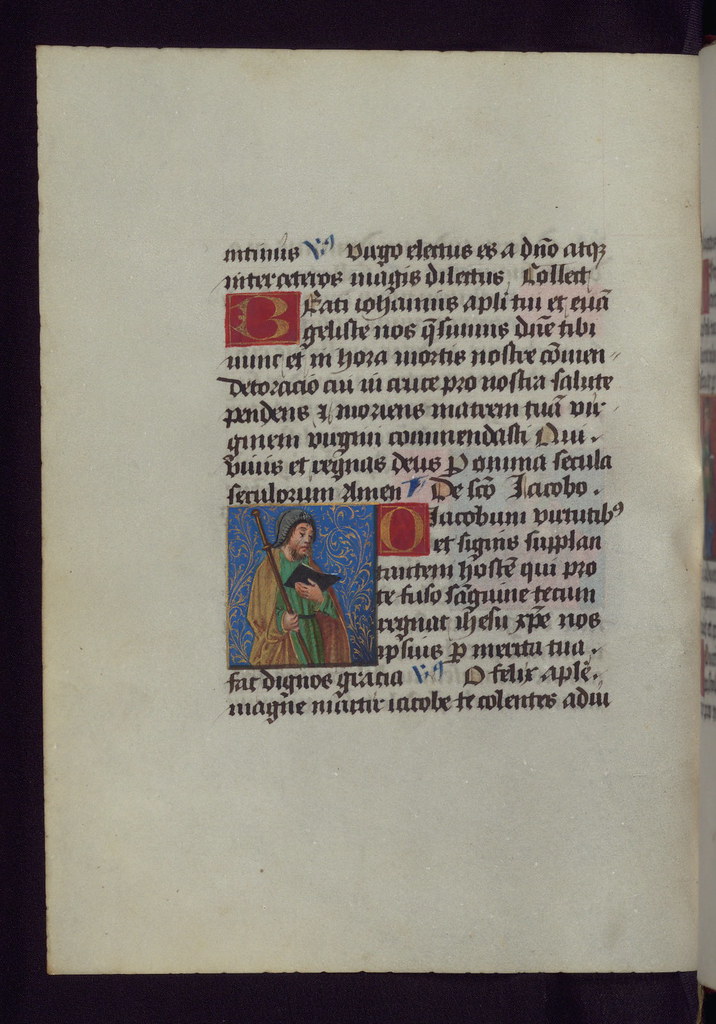

Our journey begins with James the Great, a pivotal member of Jesus’s inner circle. Born into a family of Jewish fishermen on the Sea of Galilee, his parents were Zebedee and Salome, the latter being a sister of Mary, the mother of Jesus. This familial connection thus made James the Great a cousin of Jesus, a relationship that placed him intimately within the nascent Christian movement. He is designated as “the Greater” to distinguish him from the other apostle named James, “the Lesser,” with this appellation signifying either older or taller, rather than implying greater importance.

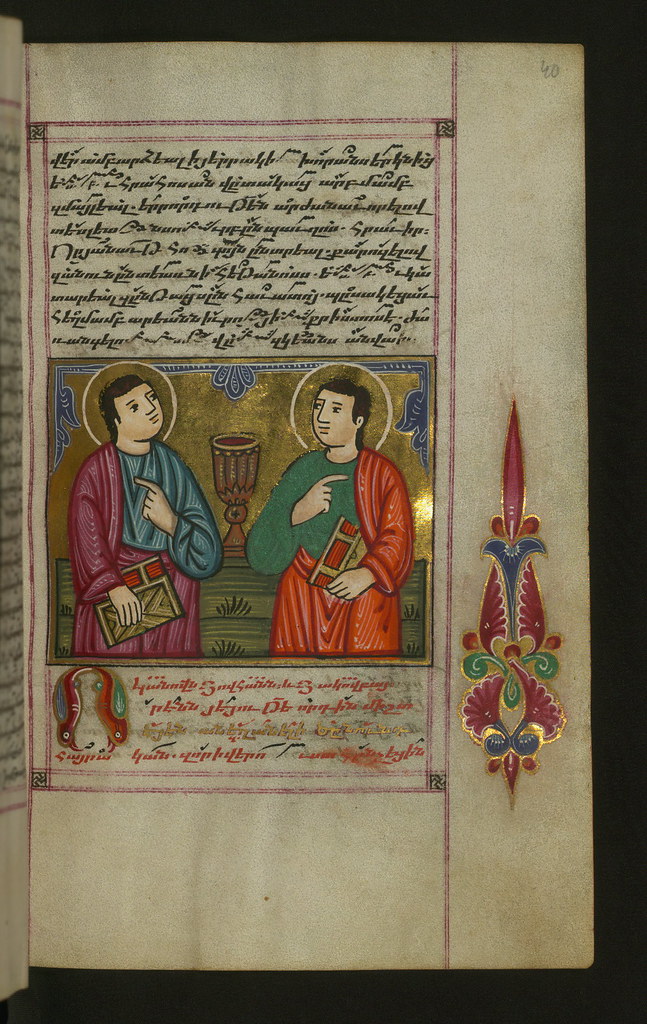

James the Great, brother of John the Apostle, stands out as one of the very first disciples to heed Jesus’s call. The Synoptic Gospels recount that James and John were engaged in their fishing preparations with their father by the seashore when Jesus extended the invitation for them to follow him. This immediate response underscores a profound commitment and readiness for the spiritual transformation that lay ahead, marking them as foundational pillars of the early church.

Indeed, James, alongside his brothers John and Peter, constituted an informal triumvirate among the Twelve Apostles, indicating a unique closeness to Jesus. This privileged position allowed them exclusive presence at three particularly significant occasions during Jesus’s public ministry: the raising of Jairus’ daughter, the transfiguration of Jesus, and Jesus’ agony in the Garden of Gethsemane. These intimate moments underscore his integral role in bearing witness to Christ’s most profound miracles and struggles.

Despite their favored status, James and his brother were not without human failings, earning them the nickname Boanerges, or “Sons of Thunder,” a testament to their fiery temper. This characteristic was evident when they sought to call down fire on a Samaritan town, an act for which they were promptly rebuked by Jesus. In another instance, James and John, or in an alternative tradition, their mother, audaciously asked Jesus to grant them seats of honor at his right and left in his glory, an ambition that Jesus rebuked, explaining that such honor was not his to grant and querying their readiness to endure the trials he faced. This episode caused annoyance among the other apostles, highlighting the human dynamics within the early apostolic group.

Tragically, James the Great holds the distinction of being the first apostle martyred, and the second to die after Judas Iscariot. The Acts of the Apostles starkly records that “Herod the king,” typically identified as Herod Agrippa, had James executed “by the sword,” an act most historians believe to have been a beheading. This swift and brutal end, perhaps triggered by his renowned fiery temper, marks a solemn moment in the early Christian narrative, standing in stark contrast to the miraculous liberation of Saint Peter, a “mystery of divine providence,” as noted by F. F. Bruce.

Beyond his earthly ministry and martyrdom, the veneration of Saint James the Great evolved into a powerful cultural and religious phenomenon, especially in Spain. He is revered as the patron saint of Spain, and tradition holds that his remains are interred in Santiago de Compostela in Galicia. The name Santiago itself is a local evolution of the Latin genitive Sancti Iacobi, meaning “(church or sanctuary) of Saint James,” later becoming a personal name in Spanish and Portuguese.

This sacred site became the destination of the fabled “Way of St. James,” an ancient pilgrimage route that has drawn Western European Catholics since the Early Middle Ages. Its modern resurgence was significantly propelled by Walter Starkie’s 1957 book, The Road to Santiago. The Pilgrims of St. James has seen hundreds of thousands of pilgrims annually undertaking the final kilometers to qualify for a Compostela. Special significance is attached to “Holy Years,” or Jacobean holy years, which occur when July 25th, St. James’s feast day, falls on a Sunday. These jubilee years follow a specific 6-5-6-11 pattern, with the most recent being in 2021, and the next anticipated in 2027.

His feast day is observed on July 25th across Roman Catholic, Orthodox, True Orthodox, Anglican, Lutheran, and various other Protestant churches. This date is traditionally believed to be the anniversary of his martyrdom in 44 AD, although some historians suggest its selection might have coincided with the feast day of Saint Christopher. Additionally, he is commemorated on April 30th in the Orthodox Christian liturgical calendar and on June 30th for the Synaxis of the Apostles. Notably, July 25th also marks the National Day of Galicia, honoring its patron saint.

The historical site of James’s martyrdom is traditionally located within the Armenian Apostolic Cathedral of St. James in Jerusalem’s Armenian Quarter. Specifically, the Chapel of Saint James the Great, situated to the left of the sanctuary, is the revered spot where King Agrippa purportedly ordered his beheading. His head is believed to rest beneath the altar, identified by a piece of red marble and perpetually illuminated by six votive lamps, a poignant tribute to his sacrifice.

The legend of Saint James’s mission in Hispania and his subsequent burial in Compostela is a cornerstone of Spanish religious tradition, summarized in the 12th-century Historia Compostelana. This narrative posits two central tenets: first, that James preached the gospel in Hispania in addition to the Holy Land; and second, that following his martyrdom, his devoted followers miraculously transported his body by sea to Hispania. They are said to have landed at Padrón on the Galician coast, from where they carried it overland for burial at Santiago de Compostela.

According to ancient local tradition, a profound event occurred on January 2nd, AD 40, while James was evangelizing in Hispania: the Virgin Mary appeared to him on the bank of the Ebro River at Caesaraugusta, now Zaragoza. This apparition occurred upon a pillar, which is still venerated today within the Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar. Following this divine encounter, Saint James returned to Judaea, where he was beheaded by Herod Agrippa I in AD 44. The translation of his relics to Galicia is further embellished by a series of miraculous events, including his decapitated body being carried by angels in a rudderless boat to Iria Flavia, where a massive rock then miraculously enclosed his body.

Tradition recounts that James’s disciples, Theodore and Athanasius, sought a burial place from Queen Lupa upon their arrival in Iria Flavia. Initially, Lupa attempted to deceive and kill them, but their faith and the protective presence of the holy cross allowed them to escape and even tame wild bulls on Pico Sacro, intended for their demise. Witnessing these astounding events, Queen Lupa converted to Christianity and aided in constructing the apostle’s tomb in Libredon. The eventual discovery of the saint’s relics in the 9th century by Pelayo in the Libredon forest, during the time of Bishop Theodemir and King Alfonso II, solidified these traditions as the basis for the pilgrimage route that would profoundly shape the spiritual landscape of Western Europe.

An even later and highly influential tradition recounts Saint James’s miraculous appearance to fight for the Christian army during the legendary battle of Clavijo, earning him the moniker Santiago Matamoros, or “Saint James the Moor-slayer.” This image, often depicted with a scallop shell and the mantle of his military order, became deeply ingrained in Spanish identity. The cry “¡Santiago, y cierra, España!” (“St. James and strike for Spain”) served as the traditional battle cry of medieval Spanish Christian armies, a testament to his perceived divine intervention. Miguel de Cervantes, in Don Quixote, underscores this deep cultural resonance, explaining that “the great knight of the russet cross was given by God to Spain as patron and protector.” His enduring emblem, the scallop shell, became a widespread symbol, worn by pilgrims and reflected in the names for scallops across various European languages.

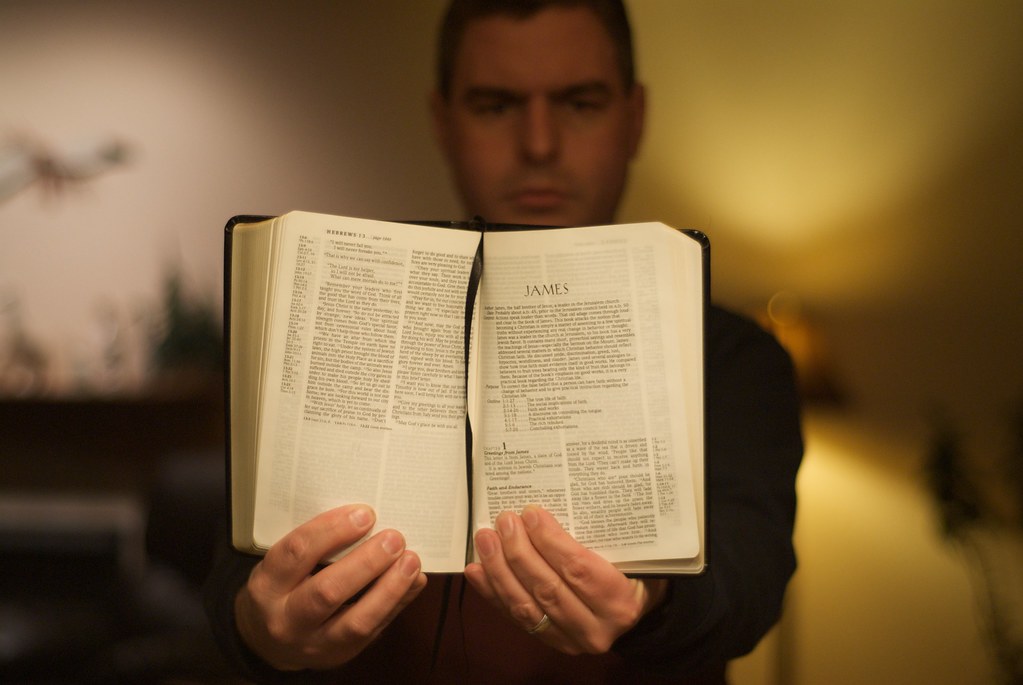

Flowing from this rich historical and legendary tapestry, we turn to the New Testament’s Book of James, an epistle distinct from the narrative of James the Great, the Apostle. The author of this powerful letter identifies himself simply as James, and scholarly consensus attributes its authorship not to James the Apostle who died in 44 AD, but most plausibly to James, the brother of Jesus and a prominent leader of the Jerusalem council. This James was initially skeptical of Jesus’s mission, even challenging and misunderstanding him. However, he later became a central figure, recognized as a “pillar” of the church by Paul, and a key leader in the pivotal Jerusalem council, so well-known that Jude could simply identify himself as “a brother of James.”

Dated likely before 50 AD, the Book of James stands as potentially the earliest of all New Testament writings, possibly even predating Galatians. Its distinctively Jewish character strongly suggests it was composed when the church remained predominantly Jewish. This early dating is further supported by the simple church order reflected within the text, referring to officers as “elders” and “teachers,” without mention of the later controversy over Gentile circumcision. Furthermore, the use of the Greek term synagoge to denote the church’s meeting place underscores its Jewish context.

The recipients of this epistle are explicitly identified as “the twelve tribes scattered among the nations,” a phrase most naturally applying to Jewish Christians. These were likely believers from the early Jerusalem church who were dispersed due to persecution, spreading as far as Phoenicia, Cyprus, and Syrian Antioch. As the leader of the Jerusalem church, James wrote with authority as a pastor, offering instruction and encouragement to his dispersed community facing significant difficulties, cementing his influence not just as a historical figure but as a guiding voice.

The Book of James possesses several distinctive characteristics that set it apart. Its unmistakable Jewish nature, evidenced by the use of the Hebrew title for God, Kyrios Sabaoth, “Lord Almighty,” is paramount. Crucially, it emphasizes “vital Christianity, characterized by good deeds and a faith that works,” advocating that “genuine faith must and will be accompanied by a consistent lifestyle.” The epistle’s simple organization and remarkable familiarity with Jesus’s teachings, particularly those preserved in the Sermon on the Mount, are also striking. Passages within James frequently parallel Christ’s words, such as comparing 2:5 with Matthew 5:3, 3:10-12 with Matthew 7:15-20, and 5:12 with Matthew 5:33-37, demonstrating a direct lineage of wisdom. Its profound similarity to Old Testament wisdom writings, notably Proverbs, further solidifies its authoritative guidance on practical living, all conveyed in excellent Greek.

The epistle begins with greetings, swiftly transitioning into profound insights on trials and temptations. James exhorts believers to “Consider it pure joy, my brothers, when you encounter trials of many kinds, because you know that the testing of your faith develops perseverance.” This counterintuitive perspective encourages a transformative outlook on adversity, urging believers to allow perseverance to “finish its work, so that you may be mature and complete, not lacking anything.” For those who lack wisdom, a crucial commodity in navigating life’s complexities, the instruction is clear: “He should ask God, who gives generously to all without finding fault, and it will be given to him.” However, this asking must be “in faith, without doubting,” as doubt renders one unstable and unlikely to receive.

James then delves into the origin of temptation, emphatically stating that “When tempted, no one should say, ‘God is tempting me.’ For God cannot be tempted by evil, nor does He tempt anyone.” Instead, temptation arises from “one’s own evil desires,” which, when conceived, give birth to sin, and ultimately, sin, when “full-grown, gives birth to death.” In stark contrast, “Every good and perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of the heavenly lights, with whom there is no change or shifting shadow,” a powerful affirmation of divine constancy and benevolence.

One of the most profound and often debated sections of the Book of James is its unequivocal declaration on faith and deeds. James challenges mere verbal profession, asking, “What good is it, my brothers, if someone claims to have faith, but has no deeds? Can such faith save him?” He illustrates this with a poignant example: if a brother or sister lacks clothing and daily food, and one merely offers well wishes without providing for their physical needs, “what good is that?” This leads to the powerful conclusion that “faith by itself, if it does not result in action, is dead.” To demonstrate true faith, one must show it through actions, echoing the profound truth that “As the body without the spirit is dead, so faith without deeds is dead.” He cites the examples of Abraham, whose faith was perfected by offering Isaac, and Rahab, who was justified by her actions in welcoming the spies.

Another significant theme is the mastery of the tongue, a small yet incredibly powerful member of the body. James cautions that “Not many of you should become teachers, my brothers, because you know that we who teach will be judged more strictly.” He acknowledges that “We all stumble in many ways,” but highlights that control over one’s speech signifies true perfection, allowing control over the “whole body.” Likening the tongue to a small bit that guides a horse or a tiny rudder that steers a massive ship, he underscores its immense influence. He dramatically declares that “The tongue also is a fire, a world of wickedness among the parts of the body. It pollutes the whole person, sets the course of his life on fire, and is itself set on fire by hell.” The paradox of blessing God and cursing men with the same tongue is presented as an unacceptable contradiction, emphasizing the need for consistency in speech.

James then contrasts two kinds of wisdom: earthly, unspiritual, demonic wisdom characterized by “bitter jealousy and selfish ambition,” which leads to “disorder and every evil practice,” versus the “wisdom from above.” The latter is beautifully described as being “first of all pure, then peace-loving, gentle, accommodating, full of mercy and good fruit, impartial, and sincere.” This divine wisdom fosters righteousness and peace, culminating in the understanding that “peacemakers who sow in peace reap the fruit of righteousness.”

The epistle also contains stern warnings against worldliness and pride. James confronts the origins of conflicts and quarrels, attributing them to “passions at war within you.” He exposes the futility of asking with wrong motives, desiring to squander blessings on pleasures. Friendship with the world, he declares unequivocally, “is hostility toward God,” making one an “enemy of God.” A profound call to humility follows: “God opposes the proud, but gives grace to the humble.” The counsel is to “Submit yourselves, then, to God. Resist the devil, and he will flee from you. Draw near to God, and He will draw near to you.” This spiritual cleansing requires purifying hearts and hands, a turning laughter to mourning and joy to gloom, for it is by humbling oneself before the Lord that one will be exalted.

A specific warning is issued to “rich oppressors.” James laments, “Come now, you who are rich, weep and wail over the misery to come upon you.” He foresees their material possessions rotting, their gold and silver corroding, their very wealth testifying against them and consuming their flesh like fire. The injustice of withholding wages from workmen is condemned, with the “cries of the harvesters” reaching the ears of “the Lord of Hosts.” The rich who have lived in “luxury and self-indulgence” and “fattened their hearts in the day of slaughter” are particularly rebuked for condemning and murdering the righteous who offered no resistance.

Finally, James offers miscellaneous exhortations vital for Christian living. He urges patience in suffering, using the farmer’s patient wait for rain as an example, reminding believers that “the Lord’s coming is near.” He cautions against complaining about one another and strictly forbids swearing oaths, advocating for simple honesty: “Simply let your ‘Yes’ be yes, and your ‘No,’ no.” The power of prayer is deeply emphasized: “Is any one of you suffering? He should pray. Is anyone cheerful? He should sing praises.” For the sick, calling the elders of the church to pray and anoint with oil is prescribed, with the assurance that “the prayer offered in faith will restore the one who is sick.” Confession of sins to one another and mutual prayer are encouraged, for “The prayer of a righteous man has great power to prevail,” exemplified by Elijah’s powerful intercession for rain. The epistle concludes with a powerful call to restorative action: “if one of you should wander from the truth and someone should bring him back, consider this: Whoever turns a sinner from the error of his way will save his soul from death and cover over a multitude of sins.

The figures named James, particularly James the Great, the Apostle, and the author of the epistle, together weave a remarkable tapestry of faith, action, and enduring wisdom. From the shores of Galilee to the hallowed grounds of Compostela, and from the intimate moments with Jesus to the practical, challenging truths penned for the scattered church, the legacy of James continues to resonate. His life serves as a testament to the transformative power of discipleship, while the inspired words of the Book of James offer timeless guidance on cultivating a vibrant, active faith that confronts hypocrisy, champions humility, and steadfastly pursues righteousness. It is a profound and vital testament, echoing through the centuries, inviting all to embody a faith that is not merely heard but deeply lived.