The 1970s, a decade often shortened to the ‘Seventies’ or the ”70s’, marked a profound chapter in world history, commencing on January 1, 1970, and concluding on December 31, 1979. It was an era historians in the 21st century increasingly view as a ‘pivot of change,’ characterized by significant economic upheavals that followed the post-war economic boom. This period was a tapestry woven with global conflicts, societal shifts, and nascent technological advancements that would lay the groundwork for our modern digital landscape, yet much of daily life remained anchored in the tangible, analog world.

Amidst political shifts, international conflicts like the final years of the Vietnam War, the 1973 oil crisis, and the dramatic Iranian Revolution of 1979, the decade also experienced ‘great technological and scientific advances.’ The appearance of the first commercial microprocessor, the Intel 4004, in 1971 heralded a ‘profound transformation of computing units’ from ‘rudimentary, spacious machines’ towards ‘portability and home accessibility.’ However, this digital dawn was just beginning, and for most, the world was experienced through simpler, more direct, and undeniably analog means. It was a time when ‘social progressive values that began in the 1960s, such as increasing political awareness and economic liberty of women, continued to grow,’ and an era where the material culture reflected a specific ethos of design and interaction.

It is within this fascinating historical context that we find a host of analog technologies that, while perhaps overshadowed by the digital revolution they indirectly preceded, continue to exert a subtle but undeniable influence today. From the ways we communicated to how we consumed entertainment, traveled, and even played, these simple analog tools defined an era. Today, in our hyper-connected, often overwhelming digital age, many are discovering a renewed appreciation for the qualities these 70s technologies embodied—simplicity, tangibility, durability, and a certain intentionality in interaction. Let us take an analytical journey back to the ’70s to explore some of these foundational analog elements and ponder their quiet, yet significant, modern resurgence.

1. **Fixed-Line Telephony**In an era long before smartphones and instant messaging, the fixed-line telephone stood as the undisputed cornerstone of long-distance communication, a true analog marvel. Integral to the broad category of ‘Electronics and communications’ mentioned in the historical context, these devices represented a tangible link to the outside world. The experience was inherently different from today’s ubiquitous digital exchanges; each call was an event, requiring a physical dial or button press, and a direct, unmediated connection that fostered focused conversation. The reliance on physical infrastructure, copper wires stretching across cities and continents, underscored the analog nature of this essential technology.

During the 1970s, the landline was not just a convenience; it was a societal hub. Households often shared a single telephone, strategically placed in a central location, embodying a collective approach to communication. The mechanical clicks of the rotary dial, the distinct ringing patterns, and the clarity (or occasional static) of an uncompressed voice signal were all hallmarks of an analog experience that is now largely a relic. This directness, free from the distractions of a multi-functional device, cultivated a unique form of engagement, where the act of speaking and listening was paramount.

The modern ‘comeback’ of fixed-line telephony isn’t about widespread re-adoption, but rather a profound appreciation for its inherent qualities. In an age of digital noise and constant notifications, the landline symbolizes a retreat to simplicity and intentionality. Designers increasingly draw inspiration from its robust, single-purpose aesthetic, influencing retro-modern electronics. Furthermore, the concept of a dedicated communication channel, free from the data collection and algorithmic mediation of digital platforms, resonates with growing privacy concerns, making the analog ideal a powerful, forward-looking counter-narrative.

2. **Broadcast Television and Radio**As cornerstones of ‘Popular culture’ in the 1970s, broadcast television and radio were the primary conduits for news, entertainment, and shared cultural experiences, operating entirely on analog signals. The context highlights that ‘Television’ was a significant aspect of popular culture in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa, and Japan. These mediums offered a communal experience, often gathering families around the glowing screen or the rich sound of a radio. The technology itself was about capturing and decoding electromagnetic waves, converting them into images and sounds, a distinctly analog process that connected millions.

The programming of the 1970s, from news reports on ‘The Vietnam War’ to the ‘popularity of the disco music genre and subculture’ that peaked ‘during the mid-to-late 1970s,’ was delivered through these over-the-air signals. Viewers and listeners were passive recipients, bound by broadcast schedules and the limitations of antenna reception. This ‘lean-back’ experience fostered a different kind of cultural consumption, one where content was curated and delivered, creating shared national or regional conversations around prominent events and popular programs, bridging societal divides and influencing public discourse in an immediate, yet physically constrained, manner.

Today, while digital streaming dominates, the appeal of analog broadcast endures, manifesting as a cultural ‘comeback’ in several forms. Retro-styled radios and televisions are popular design objects, celebrated for their aesthetic and tactile qualities. More significantly, there’s a growing movement towards ‘digital minimalism’ and a desire to disconnect from algorithm-driven content feeds, prompting a re-evaluation of linear, scheduled programming. The pure, unadulterated audio of FM radio or the nostalgic glow of a CRT television screen offers a sensory experience distinct from the pixel-perfect precision of modern digital displays, suggesting a future where simpler, focused media consumption finds a renewed audience.

Read more about: The ’00s Enigma: 15 Defining Cultural Phenomena That Shaped (And Were Shaped By) The Decade

3. **Analog Recording Mediums (Vinyl & Cassettes)**The ‘Music’ section under ‘Popular culture’ implicitly points to the dominance of physical analog formats like vinyl records and cassette tapes as the primary means of consuming audio in the 1970s. This was the era when the ‘popularity of the disco music genre and subculture peaks,’ and people sought tangible ways to experience their favorite artists. These mediums were entirely analog, capturing sound waves as physical grooves or magnetic patterns, offering a warmth and fidelity that purists still champion today. The act of listening was often ritualistic: carefully placing a needle on a record, or flipping a cassette tape to side B, each a deliberate, physical engagement with the music.

Vinyl records, with their expansive album art and delicate grooves, offered a rich, immersive experience that extended beyond just the audio. Cassette tapes, on the other hand, brought portability and the revolutionary ability for personal curation through mixtapes, allowing individuals to customize their sonic landscape. This democratized music consumption, giving listeners more control over their personal libraries. Both formats were products of a time when digital compression was a distant concept, ensuring that the sound remained true to its original analog recording, providing a depth and texture often debated in audiophile circles.

The modern ‘comeback’ of vinyl records, in particular, has been nothing short of spectacular, becoming a vibrant cultural phenomenon that transcends mere nostalgia. It speaks to a craving for tangibility and intentionality in an age of ephemeral digital files. Beyond their sonic qualities, vinyl and cassettes are celebrated as artifacts, embodying a connection to music as a physical object and an art form. This resurgence isn’t just about sound quality; it’s about the entire experience—the ritual, the artwork, the permanence—a holistic appreciation for analog media that stands as a deliberate choice against the convenience of digital streams, offering a more mindful and engaged way to consume art and culture.

4. **Mechanically-Focused Automobiles**The category ‘Automobiles’ in the context implicitly refers to vehicles that were, for the vast majority of the 1970s, mechanically rather than electronically controlled. This was an era where the driving experience was more direct, less mediated by sophisticated digital systems, offering a pure, analog connection between driver and machine. While ‘Industrialized countries experienced an economic recession due to an oil crisis caused by oil embargoes by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries,’ cars remained central to personal mobility, their engineering reflecting the prevalent mechanical paradigms of the time.

These vehicles were characterized by carburetors, distributors, and mechanical linkages, providing a tactile and visceral driving experience. Diagnostics often relied on a wrench and a keen ear, rather than a computer interface. The absence of complex onboard computers meant that repairs were often more accessible and understandable to the average mechanic, fostering a deeper, more direct relationship with the vehicle. The design ethos prioritized functional mechanics over digital amenities, resulting in cars that, while perhaps less efficient by modern standards, offered a raw, unfiltered sense of propulsion and control.

The modern ‘comeback’ for mechanically-focused automobiles manifests as a growing appreciation among enthusiasts for the purity of the driving experience. Vintage cars from the 70s are highly sought after, not just for their aesthetic, but for the distinct feel of their analog controls and the engagement they demand from the driver. This movement is a counterpoint to the increasingly automated and digitally assisted modern vehicles, speaking to a desire for greater involvement and skill behind the wheel. It highlights a cultural shift towards valuing the craft of engineering and the direct, unmediated sensory feedback that only a mechanically-oriented machine can provide, influencing contemporary car design towards more driver-centric interfaces.

5. **Traditional Rail Systems**The mention of ‘Rail’ as a distinct category under ‘Technology’ in the context underscores the enduring significance of traditional railway systems in the 1970s. These systems relied on a blend of robust mechanical engineering and established electrical signaling, operating largely without the advanced digital control systems that define modern high-speed networks. In an era when ‘the economy of Japan witnessed a large boom’ and its ‘economic growth surpassed the rest of the world,’ rail transportation continued to be a backbone of commerce and passenger travel, demonstrating the efficiency and reliability of large-scale analog infrastructure.

The operation of these 70s rail networks was a complex orchestration of physical switches, trackside signals, and human operators, often communicating through analog radio or telegraph systems. The trains themselves were mechanical marvels, powered by diesel or electric traction, their movement governed by precise, predictable physical laws. This reliance on tangible, visible infrastructure—the tracks, the rolling stock, the stations—created a sense of permanence and an almost poetic rhythm of travel, a stark contrast to the invisible, data-driven complexities of today’s transportation logistics. The experience was about the journey itself, often through scenic routes, rather than merely the destination.

The ‘comeback’ of traditional rail systems is less about literal technological reversal and more about a renewed societal appreciation for their inherent benefits and qualities. In an age of congested roads and often-stressful air travel, the deliberate pace and communal aspect of train travel are finding favor again. There’s a cultural shift towards valuing sustainable transportation, the ability to work or relax during transit, and the romantic notion of journeying by rail. This re-evaluation influences urban planning and infrastructure development, with renewed investment in accessible, efficient, and often aesthetically pleasing rail networks that hark back to the reliability and human scale of their analog predecessors, seeking to integrate timeless design principles with modern needs.

Read more about: The Automotive Exodus: Unpacking the 14 Critical Reasons Why Diesel Engines Are Fading from Our Markets

6. **Slide Projectors / Film-based Visual Media**While not explicitly named, the inclusion of ‘Film’ under ‘Popular culture’ in the 1970s context strongly implies the prevalent use of film-based visual media, including personal photographic slides and cinematic reels. This was the era before digital photography and ubiquitous video, where capturing and sharing visual memories and stories was an entirely analog process. Whether projecting family vacation photos in a darkened living room or watching a blockbuster at the local cinema, the technology relied on light passing through celluloid, creating images on a screen—a fundamentally different paradigm from today’s digital displays.

The process involved tangible components: rolls of film to be developed, individual slides meticulously mounted, and then projected using a mechanical and optical device. The ritual of setting up a slide projector, aligning the image, and clicking through a sequence of photographs was a social event, a shared storytelling experience. Similarly, the magic of the cinema was rooted in the projectionist’s craft, meticulously spooling and playing film reels. These were not just technologies for viewing; they were technologies for *experience*, emphasizing presence, shared attention, and the finite, precious nature of each captured image.

The modern ‘comeback’ for film-based visual media is multi-faceted. In professional and amateur photography, there’s a significant resurgence of interest in analog film, lauded for its unique aesthetic qualities, depth of color, and dynamic range that digital often struggles to replicate. Beyond this, the cultural appreciation extends to the ritualistic nature of film use—the anticipation of development, the tactile quality of a printed photograph, and the deliberate act of curating and projecting a finite set of images. This movement reflects a desire for authenticity, a counter-reaction to the endless, often uncurated digital stream, and a reclaiming of the slower, more deliberate artistic and personal expression that analog visual media inherently offers, fostering a mindful engagement with imagery.

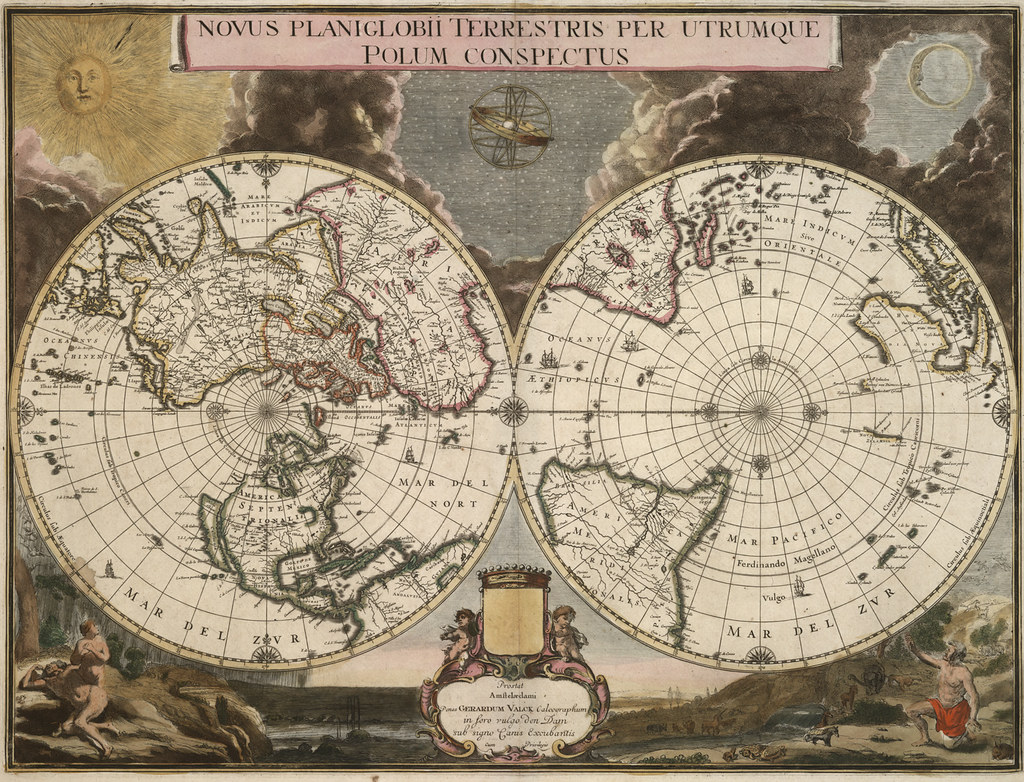

7. **Physical Maps and Atlases**In the 1970s, navigating the world, whether across continents or through local streets, was an entirely analog endeavor, predicated on the use of physical maps and atlases. The pervasive need for these navigational ‘technologies’ is implicitly understood within a world without ubiquitous digital GPS or internet-connected devices. In an era of ‘International conflicts’ and a dynamic global landscape, the ability to chart a course, understand geography, and grasp spatial relationships was critically dependent on these printed tools, making them essential for both military strategy and civilian travel alike.

These paper-based instruments were marvels of graphic design and cartographic precision. Unfolding a large road map, tracing a finger along a route, or consulting a detailed atlas to understand political boundaries or physical topography was a deliberate and engaging process. It fostered a comprehensive understanding of scale and context, encouraging users to connect places mentally rather than simply following turn-by-turn digital instructions. The act of planning a journey was a more immersive experience, involving visual interpretation, mental calculation, and a tactile interaction with the map itself.

The modern ‘comeback’ for physical maps and atlases is emerging as a niche but significant trend, reflecting a desire to reconnect with a more fundamental understanding of geography and navigation. Enthusiasts and travelers are rediscovering the joy of ‘unplugged’ exploration, where the absence of digital prompts encourages a deeper engagement with the environment and a more intuitive sense of direction. Beyond practicality, these maps are celebrated as objects of beauty and design, offering a unique aesthetic that complements contemporary minimalist trends. This resurgence signals a subtle but powerful cultural pivot, where the tangible, context-rich experience of analog navigation offers a welcome reprieve from the often-decontextualized and ephemeral nature of digital guidance, fostering a more thoughtful and mindful approach to understanding our physical world.

Continuing our analytical exploration of the enduring appeal of 1970s analog technologies, we delve into another seven marvels whose simplicity and tangible user experiences are experiencing a profound re-evaluation in our hyper-digital age. These technologies, though seemingly quaint by today’s standards, offered direct, unmediated interactions that fostered a distinct connection between user and tool, a quality increasingly sought after by those yearning for a more mindful engagement with their world. Through the lens of ‘Wired’ analysis, we uncover how these often-overlooked innovations from a pivotal decade continue to shape our understanding of utility, design, and human experience.

8. **Mechanical Watches and Clocks**In the 1970s, long before smartwatches and synchronized digital displays became ubiquitous, mechanical watches and clocks were the fundamental arbiters of time, anchoring daily life with their intricate, spring-driven movements. As societies across ‘Industrialized countries’ navigated economic shifts and social progressions like the ‘increasing political awareness and economic liberty of women’, punctuality and reliable timekeeping remained paramount, delivered by devices that were as much precision instruments as they were personal statements. These were not merely accessories but essential tools, embodying a direct, tangible connection to the flow of time itself.

The engineering within these devices represented a pinnacle of micro-mechanics, translating the continuous, flowing nature of time into a visible, sweeping second hand or the satisfying click of a manual wind. Each tick was a testament to gears, levers, and springs working in perfect, silent harmony, a contrast to the later digital displays that would present time as a series of discrete, impersonal numbers. The reliability and craftsmanship inherent in a well-made mechanical timepiece made it a trusted companion through a decade of significant global events, from ‘International conflicts’ to ‘great technological and scientific advances.’

Today, the ‘comeback’ of mechanical watches is a vibrant subculture, driven by an appreciation for traditional craftsmanship and a desire for durability and design permanence in a disposable world. They stand as a deliberate counterpoint to the relentless notifications and planned obsolescence of digital gadgets, offering a sense of connection to history and artisanal skill. This resurgence isn’t merely nostalgic; it’s a forward-looking statement about valuing enduring quality, conscious consumption, and the quiet satisfaction of interacting with a masterfully engineered analog device that requires no charging, no updates, and collects no data.

Read more about: Unwinding Time: The Case for Disconnecting from the Clock

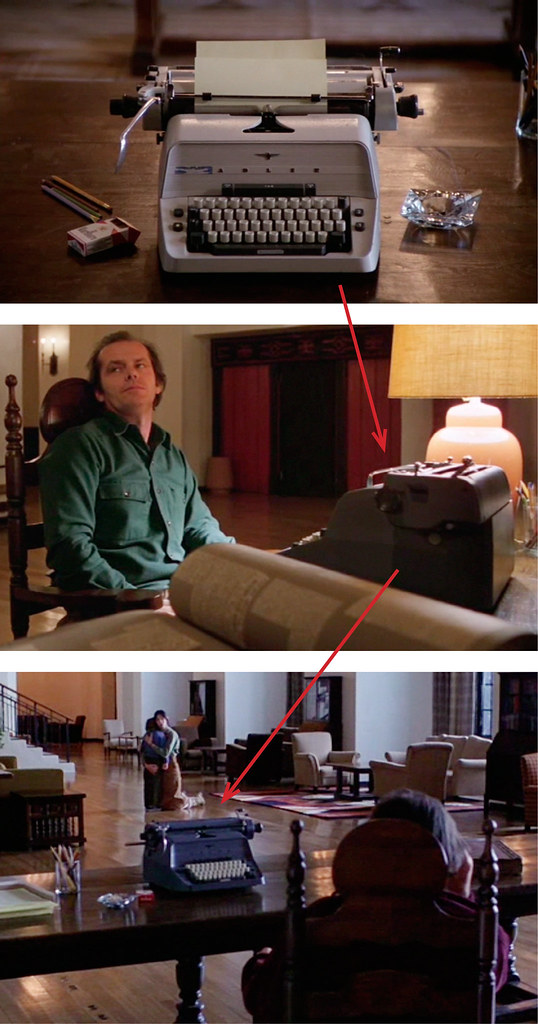

9. **Typewriters**Before the advent of personal computers and word processors, the typewriter was the undisputed workhorse for creating documents, letters, and reports throughout the 1970s. While the context notes the emergence of the ‘first commercial microprocessor, the Intel 4004 in 1971,’ hinting at the digital future, the immediate present relied heavily on these ‘rudimentary, spacious machines’ for all forms of written communication. From official memos concerning ‘the 1973 oil crisis’ to personal correspondence, the typewriter was an indispensable tool in offices and homes globally.

The act of typing on these mechanical or electro-mechanical marvels was an inherently tactile and auditory experience, profoundly different from the silent glide of modern keyboards. The distinct clack of keys, the rhythmic thud of the typebars hitting the ribbon, and the satisfying ding of the carriage return created a unique sensory feedback loop, fostering a focused and intentional approach to writing. Each keystroke was deliberate, each correction a physical act, imbuing the written word with a sense of permanence and crafted effort.

The modern ‘comeback’ of typewriters reflects a yearning for this intentionality and a break from the endless edit-and-delete cycles of digital composition. Writers, artists, and even casual users are rediscovering the joy of a distraction-free writing environment, where the physical output is immediate and final. Beyond mere nostalgia, the typewriter is embraced for its robust design, aesthetic appeal, and the creative discipline it encourages, signaling a subtle but significant cultural shift towards valuing the process of creation as much as the final product, offering a tangible connection to the craft of language in a digitally fluid world.

Read more about: Need a Reminder: The ’50s? These 12 Unforgettable Icons Were the Absolute Legends of Talent and the Decade’s Defining Moments!

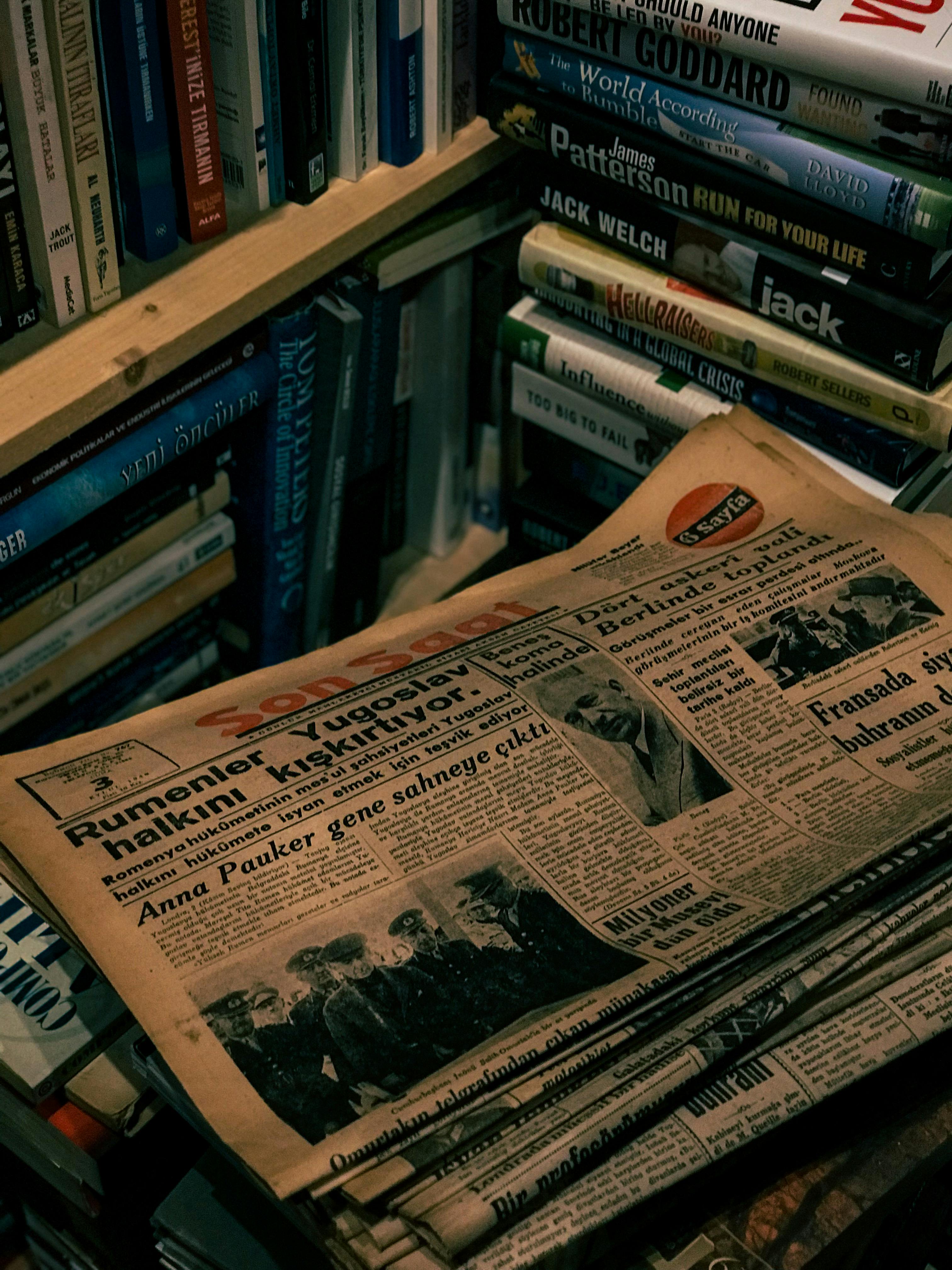

10. **Physical Books, Magazines, and Newspapers**In the 1970s, amidst a backdrop of ‘International conflicts’ and ‘social progressive values,’ physical books, magazines, and newspapers stood as the primary conduits for information, entertainment, and cultural discourse. The context repeatedly refers to major global events—from the ‘Watergate scandal’ to the ‘Iranian Revolution of 1979’ and the ‘popularity of the disco music genre’—all of which would have been extensively covered and consumed through printed media. This era was fundamentally defined by the tactile experience of turning pages, savoring printed images, and absorbing text from static layouts.

These tangible forms of media provided a focused, immersive reading experience, free from the hyperlinks, pop-ups, and endless scroll of today’s digital platforms. A newspaper was a morning ritual, a magazine a gateway to ‘Popular culture,’ and a book an extended journey of intellectual or imaginative engagement. The material presence of these items—the smell of the ink, the texture of the paper, the visual artistry of layouts—contributed to a distinct and unmediated relationship between reader and content, fostering a singular kind of attention and absorption that is increasingly rare today.

The modern ‘comeback’ for physical print, particularly books and niche magazines, is a powerful cultural statement against digital overload and algorithmic curation. Readers are rediscovering the benefits of a ‘digital detox,’ valuing the absence of distractions, the permanence of ownership, and the aesthetic pleasure of a well-designed physical object. This resurgence is not about technological regression but a conscious choice for a more mindful engagement with information and stories, reflecting a desire to reclaim agency over one’s attention and appreciate the curated, finite nature of analog content in an infinitely scrolling digital landscape.

Read more about: 15 Common Myths About World War II That Historians Have Resoundingly Debunked

11. **Instant Photography (e.g., Polaroid Cameras)**Building upon the established use of ‘Film’ within ‘Popular culture’ during the 1970s, instant cameras offered a unique, immediate gratification that stood apart from traditional film photography. While rolls of film required development, devices like the Polaroid camera delivered tangible photographic prints within moments, revolutionizing how casual memories were captured and shared. This was a technological marvel of its time, providing an on-the-spot physical artifact of events, whether they were family gatherings or documenting the social shifts and evolving ‘Role of women in society’.

The magic of watching an image materialize before your eyes, gradually revealing its colors and details, was a distinctly analog phenomenon that created a powerful, shared experience. It transformed photography from a latent process into an instant event, fostering a playful, less precious approach to image-making. These cameras fostered a sense of creative freedom and communal sharing, where the unique aesthetic — often characterized by soft focus, distinctive color palettes, and a white border for notes — became emblematic of the era’s spontaneous visual storytelling.

The ‘comeback’ of instant photography is a robust and enduring trend, driven by a desire for authenticity and tangibility that digital photos often lack. In an age where billions of digital images reside unseen on devices, the instant print offers a finite, physical manifestation of a moment, encouraging careful composition and immediate sharing. This resurgence speaks to a yearning for the imperfect, the unique, and the handcrafted aesthetic that instant film provides, acting as a delightful counterpoint to the pixel-perfect but often ephemeral nature of digital imagery, fostering a more deliberate and cherished connection to our visual memories.

12. **Analog Synthesizers and Music Production Gear**The 1970s, a decade where the ‘popularity of the disco music genre and subculture peaks,’ was a fertile ground for the dramatic rise of analog synthesizers and other electronic music production tools. Within the broad category of ‘Music’ under ‘Popular culture,’ these devices were instrumental in shaping the sonic landscape of the era, moving beyond traditional instrumentation to create entirely new textures and sounds. From the funky basslines of disco to the experimental soundscapes of progressive rock, analog synthesis provided the sonic palette for a generation of musicians and listeners.

These instruments, often characterized by racks of knobs, sliders, and patch cables, offered a hands-on, intuitive, and deeply creative interface for sound design. Musicians could physically sculpt waveforms, filter frequencies, and modulate parameters in real-time, resulting in a rich, warm, and often unpredictable sonic character that was entirely analog. This direct interaction with the electrical components and signal flow gave rise to a unique sonic fingerprint, fostering an intimate connection between the artist and the sound they were creating.

The modern ‘comeback’ for analog synthesizers is not just a niche for audiophiles or retro enthusiasts; it’s a foundational pillar of contemporary electronic music production and sound design. Musicians and producers actively seek out vintage analog gear or modern reissues for their unmistakable warmth, punch, and dynamic range that digital emulations often struggle to replicate. This resurgence underscores a critical insight: for many, the physical, tactile interface and the unique, sometimes imperfect, sonic characteristics of analog equipment foster a deeper, more engaging creative process, a testament to the enduring appeal of direct, unmediated interaction in the pursuit of sonic artistry.

13. **Manual Photography (Single-Lens Reflex Cameras)**While ‘Film-based Visual Media’ broadly covered the consumption of visual content, the 1970s saw the widespread adoption of the manual Single-Lens Reflex (SLR) camera, an analog marvel that empowered enthusiasts and professionals to take unprecedented control over their photography. In an era where ‘great technological and scientific advances’ were happening, the sophisticated mechanical and optical engineering of SLRs allowed for precise control over focus, aperture, and shutter speed, transforming photography into a craft accessible to millions who wished to document the evolving ‘social progressive values’ or capture personal milestones.

The manual SLR offered a direct, unmediated view through the lens, allowing the photographer to compose and focus with incredible precision. The tactile satisfaction of winding the film, adjusting the aperture ring, and hearing the mechanical click of the shutter fostered a deeper understanding of photographic principles—light, composition, and exposure. This direct engagement with the mechanics of image capture instilled a sense of mastery and intentionality, where each photograph was a deliberate act of creation, rather than a mere digital capture.

The modern ‘comeback’ for manual photography, particularly film SLRs, is a testament to the enduring appeal of creative control and the unique aesthetic of film. Photographers are actively choosing film for its distinct grain, dynamic range, and color rendition, qualities that impart a timeless, authentic feel. This movement is a thoughtful rejection of the overwhelming automation and ephemeral nature of digital photography, embracing a slower, more deliberate process that encourages mindfulness, patience, and a deeper appreciation for the art of capturing light. It underscores a ‘Wired’ insight: sometimes, the most advanced way to create is to step back to the fundamentals, valuing the human element over digital convenience.

14. **Physical Calendars and Planners**In the 1970s, personal and professional lives, influenced by ‘increasing political awareness and economic liberty of women’ and the general busy rhythms of ‘Industrialized countries,’ were meticulously organized using physical calendars and planners. These analog tools were indispensable for managing schedules, appointments, and deadlines in a world without digital assistants or ubiquitous cloud synchronization. From wall calendars in homes to pocket-sized diaries, these tangible systems were the bedrock of personal time management.

Interacting with a physical planner involved a deliberate act of writing, prioritizing, and visualizing one’s schedule, fostering a strong sense of commitment and memory retention. The act of crossing off completed tasks or seeing an entire month laid out on a physical page offered a clarity and perspective that digital interfaces often abstract away. These tools were simple, reliable, and entirely private, reflecting an era where personal organization was a self-contained, rather than networked, endeavor.

The ‘comeback’ of physical calendars, bullet journals, and aesthetic planners in our digital age is a fascinating paradox, revealing a deep-seated human need for tangible control over our time and tasks. Many find that the act of physically writing down appointments and goals enhances memory, reduces screen fatigue, and provides a clear, uncluttered overview of their commitments. This resurgence is a profound cultural statement against the endless digital stream, offering a grounded, intentional approach to productivity and mindfulness that prioritizes clarity and personal connection over the fleeting convenience of digital alerts. It’s a return to intentionality, demonstrating that sometimes the most effective technology for planning isn’t electronic, but simply paper and pen.

Read more about: You Won’t Believe These 14 Bonkers Ideas That Made Hokkaido’s F Village the Coolest Place on Earth (Prepare to LOL!)

As we conclude our journey through the simple yet profound analog technologies of the 1970s, it becomes clear that their modern resurgence is far more than mere nostalgia. It is a discerning re-evaluation, a quiet revolution against the pervasive, often overwhelming currents of our digital present. Each item we’ve explored, from the satisfying click of a typewriter to the warm glow of an instant photograph, offers a potent reminder of the value of tangibility, intentionality, and unmediated human interaction. These technologies, once cornerstones of daily life, are now chosen for their deliberate constraints and rich, sensory experiences, serving as vital counterpoints to the often-ephemeral nature of digital existence. They are not simply relics of a bygone era, but enduring prototypes for a future where thoughtful engagement and authentic connection remain paramount, shaping our technological landscape in ways that are both innovative and deeply human.