For millennia, the royal scepter has stood as far more than a mere ornamental object; it is a profound and potent symbol, encapsulating the very essence of sovereign authority and the enduring right to govern. From the sun-baked lands of ancient Egypt to the philosophical heartlands of Greece and the burgeoning empires of India, this majestic staff has been a constant, tangible representation of power, often imbued with divine sanction and historical gravitas. Its presence in coronations, state ceremonies, and significant judicial moments across diverse cultures underscores its universal appeal and its pivotal role in shaping perceptions of leadership and legitimacy.

Indeed, the scepter’s journey through human history is a fascinating narrative, mirroring the evolution of governance itself. Each civilization, each monarch, and each historical epoch has woven its unique thread into the rich tapestry of the scepter’s legacy, adapting its form and meaning to reflect prevailing ideals and societal structures. It has been a silent witness to the rise and fall of empires, the establishment of enduring traditions, and the solemn transfer of authority, embodying a continuity that transcends the ephemeral nature of individual reigns.

In this exploration, we delve into the multifaceted allure of royal scepters, tracing their historical roots and cultural variations. We will uncover how these iconic staffs have not only symbolized immense power but have also inspired intricate artistry and served as anchors for deeply held beliefs about leadership, justice, and the very fabric of society. Join us as we journey through time to appreciate the enduring significance of these remarkable emblems of sovereignty.

1. **Scepters in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia**The earliest echoes of the royal scepter resonate from the cradles of civilization, particularly in the fertile crescent of Mesopotamia and the enduring kingdom along the Nile. In Ancient Egypt, the Was-scepter, alongside other forms of staves, was a paramount sign of authority. Often reaching full staff length, these symbols were so central to the pharaoh’s image and role that they are frequently described as scepters, representing their divine power and earthly dominion.

One of the most remarkable early royal scepters was unearthed in the 2nd Dynasty tomb of Khasekhemwy in Abydos, offering tangible proof of its ancient lineage. Pharaoh Anedjib is depicted on stone vessels bearing a distinctive mks-staff, further illustrating the widespread use of such emblems. However, it is arguably the heqa-sceptre, often referred to as the ‘shepherd’s crook’, that boasts the longest and most continuous history, symbolizing the pharaoh’s role as the benevolent shepherd of his people, guiding and protecting them.

The iconic Gilded Wooden sceptre of Tutankhamun stands as a testament to the artistry and symbolic weight placed upon these objects, intricately crafted to reflect the young king’s divine right to rule. Across the vast plains of Mesopotamia, the scepter also assumed a central and indispensable role. Known as *ĝidru* in Sumerian and *ḫaṭṭum* in Akkadian, it was invariably part of the royal insignia of both sovereigns and gods, signifying approval and legitimization from the heavens. This deeply embedded cultural significance is abundantly illustrated in a wealth of literary, administrative, and iconographic texts that span Mesopotamian history, showcasing its enduring power.

Perhaps one of the most compelling depictions is found on the Code of Hammurabi stela, where the god Shamash is shown holding a staff, imparting divine authority to the legendary lawgiver. This imagery powerfully conveys the belief that temporal power was bestowed by the divine, making the scepter a conduit for celestial will. The scepter, in these ancient lands, was not merely an accessory; it was the very embodiment of order, divine favor, and the absolute authority necessary to govern complex societies.

2. **The Greco-Roman Scepter: Symbols of Authority**Moving westward, the concept of the scepter, or *skēptron* as it was known in Ancient Greek, took on distinctive forms and meanings within the Greco-Roman world. Initially, it was a practical yet powerful long staff, a visual marker of status and respect. Homer’s *Iliad* vividly portrays Agamemnon wielding such a staff, and it was commonly used by esteemed elders, judges, military leaders, and priests—anyone who commanded authority and respect within their community.

Representations on painted vases from the era depict these scepters as elegant, long staffs, often capped with a gleaming metal ornament, signifying their importance. When the scepter was borne by the mighty Zeus, king of the gods, or the formidable Hades, ruler of the underworld, it was uniquely distinguished by a bird adorning its tip. This specific symbolism underscored the divine connection and ultimate power of these deities, lending an almost sacred aura to the scepter itself.

Crucially, this symbol of Zeus imparted an inviolable status to the *kerykes*, the revered heralds. Protected by what could be seen as an ancient precursor to modern diplomatic immunity, these heralds carried the scepter as they journeyed to parley, ensuring their safety and respect. A poignant example from the *Iliad* recounts Agamemnon entrusting his scepter to Odysseus when sending him to negotiate with the Achaean leaders, highlighting its role as a symbol of delegated, yet supreme, authority.

Across the Adriatic, the Etruscans, renowned for their sophisticated artistry and powerful city-states, also embraced scepters of extraordinary magnificence. These grand staffs were wielded by their kings and high priests, symbolizing both temporal and spiritual authority. The walls of Etruria’s painted tombs are adorned with numerous representations of such lavish scepters, providing invaluable insights into their design and usage. Today, museums like the British Museum, the Vatican, and the Louvre proudly house Etruscan scepters crafted from gold, elaborately and minutely ornamented, showcasing the unparalleled skill of their ancient artisans.

The Roman scepter, *sceptrum*, undoubtedly drew much of its inspiration from these Etruscan traditions. During the Roman Republic, an ivory scepter, known as the *sceptrum eburneum*, was a distinct mark of consular rank, signifying the highest civil office. It was also bestowed upon victorious generals who had earned the title of *imperator*, a testament to their military prowess. This tradition of using the scepter as a symbol of delegated authority to legates later found an echo in the marshal’s baton, which became a powerful military emblem in subsequent eras. Under the grandeur of the Roman Empire, the *sceptrum Augusti* became the exclusive preserve of the emperors, frequently fashioned from ivory and crowned with a majestic golden eagle, a potent symbol of Rome’s imperial might. These imperial scepters are often depicted on medallions of the later empire, showing a half-length figure of the emperor, holding the *sceptrum Augusti* in one hand and, in the other, the orb surmounted by a small figure of Victory, representing universal dominion and triumph.

3. **The Scepter in Biblical Narratives**The enduring power of the scepter as a symbol transcends mere historical artifacts, finding its way into the profound spiritual and prophetic texts of the Biblical tradition. One of the most significant references appears in the Book of Genesis, within Jacob’s blessing to his sons. Genesis 49:10 declares, “The sceptre shall not depart from Judah, nor a lawgiver from between his feet, until Shiloh come; and unto him shall the gathering of the people be.”

This prophecy profoundly links the scepter, an emblem of kingship and legal authority, directly to the lineage of Judah. It foretells a continuous line of leadership and legislative power stemming from Judah, a promise that culminates with the arrival of ‘Shiloh’ – a figure widely interpreted to be the Messiah. The phrase ‘nor a lawgiver from between his feet’ further reinforces the idea of dynastic succession and the enduring presence of governance and justice within this specific tribe. The scepter, in this context, is not just a material object but a divine guarantee, a testament to God’s covenant and the destined role of Judah in Israel’s history.

Centuries later, the scepter reappears dramatically in the Book of Esther, illustrating its immediate and formidable power within a royal court. The narrative unfolds with Queen Esther risking her life by approaching King Ahasuerus unbidden, an act punishable by death unless the king extended his golden scepter towards her. The text vividly states: “When the king saw Esther the queen standing in the court, she obtained favor in his sight; and the king held out to Esther the golden scepter that was in his hand. So Esther came near, and touched the top of the scepter.” (Esther 5:2).

This scene powerfully underscores the absolute authority vested in the monarch and the life-or-death significance of the scepter’s gesture. The act of extending the scepter was an explicit display of mercy, a unilateral decision by the king that overruled strict court protocol and granted an audience, thereby saving Esther’s life and setting in motion the chain of events that would ultimately preserve her people. The golden scepter here serves as the ultimate arbiter of fate, a tangible manifestation of the Persian king’s unchallengeable decree and clemency.

4. **India’s Scepters: Ancient Wisdom to Modern Transfers**The Indian subcontinent, with its rich tapestry of ancient kingdoms and philosophical traditions, also holds a deep reverence for the scepter as a symbol of just rule and sovereign authority. The ancient Tamil work of *Tirukkural*, dated before the 5th century CE, dedicates significant insight to this very concept. Its chapters 55, known as *Sengol*, and 56, *Kondungol*, meticulously deal with the nature of the just and cruel scepter, respectively. These chapters profoundly extend the ethical discussions concerning a ruler’s conduct, integrating the scepter directly into the philosophical framework of governance.

The treatise emphasizes a powerful notion: “it was not the king’s spear but the just sceptre, known as ‘Sengol’ in Tamil, that bound him to his people—and to the extent that he guarded them, his own good rule would guard him.” This eloquent statement beautifully captures the essence of righteous leadership, suggesting that a ruler’s true strength and legitimacy did not lie in military might, but in their unwavering commitment to justice and the welfare of their subjects. The *Sengol* thus became a symbol of a reciprocal relationship, where the king’s just rule was both a duty and a shield.

This practice of employing a symbolic scepter during coronations was deeply ingrained in the traditions of ancient Indian kingdoms and dynasties, notably the Chola kings. These ceremonial staffs were not mere ceremonial props; they embodied the sacred transfer of power and the solemn vows undertaken by the new monarch to uphold dharma and ensure prosperity. The *Sengol* was a powerful visual and spiritual anchor for the legitimacy of their reign, connecting the present ruler to a long and venerable lineage of just governance.

In a remarkable modern echo of this ancient tradition, a significant *Sengol* was presented to Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, on 14 August 1947. This historic presentation by the Thiruvaduthurai Adheenam was intended to symbolize the transfer of power from British colonial rule to independent India, directly drawing upon the ancient Hindu custom of transferring authority. It was a poignant moment, invoking a deep sense of historical continuity and indigenous sovereignty at the dawn of a new nation.

However, the immediate historical significance of this specific *Sengol* encountered a period of oversight. For a considerable time, it was displayed in the Allahabad Museum under the rather understated and, as later revealed, wrongly marked designation of ‘Golden walking Stick Gifted to Pt Jawahar Lal Nehru.’ This mislabeling obscured its profound symbolic meaning for decades. In 2023, the government of India made a decision to rectify this, installing this gold-plated scepter in the newly inaugurated Indian Parliament. The presentation of the *Sengol* sceptre to the first Indian Prime Minister in 1947 was claimed as a ‘symbol of transfer of power from British to India,’ a claim that has, predictably, stirred debates among a few historians who point to a lack of explicit contemporary sources portraying the event as a formal, official transfer ceremony. Regardless, its recent prominent re-installation underscores the powerful resonance that this ancient emblem of justice and authority continues to hold in the national consciousness.

5. **Christendom’s Scepters: The Cross and the Dove**The advent of Christianity brought a profound transformation to the symbolism of the royal scepter. Moving beyond purely earthly or pagan representations, scepters increasingly began to feature a cross at their apex, a powerful emblem of Christian faith. This crucial alteration signaled a shift in the perceived origin of monarchical legitimacy, grounding a ruler’s authority in divine will and solidifying the fusion of temporal power with spiritual sanction throughout the Christian world.

During the extensive Middle Ages, the designs adorning the summit of these ceremonial staffs showcased considerable variety. While the cross became a dominant motif, artisans and monarchs often explored a range of finials, each imbued with specific theological or secular meaning. These variations reflected diverse regional traditions, the specific patron saints of a kingdom, or even the personal devotions of the reigning monarch, creating a rich tapestry of symbolic artistry that transcended mere power, becoming a complex theological statement.

In England, a particularly distinctive tradition emerged quite early, involving the concurrent use of two distinct scepters from the reign of Richard I. These were differentiated: one tipped with a cross, overtly symbolizing Christian faith and divine authority, and the other crowned with a dove, associated with the Holy Spirit and peace. This dual symbolism reflected a nuanced understanding of kingship, encompassing both the assertiveness of righteous rule and the spiritual guidance essential for benevolent governance, becoming integral to English coronation rituals for centuries.

France, too, developed unique ceremonial scepters, notably the royal scepter adorned with the fleur-de-lys, a powerful emblem of the French monarchy. Complementing this was the *main de justice*, or ‘hand of justice’, featuring an open hand in a gesture of benediction at its summit. This powerful image unequivocally underscored the king’s paramount role as the ultimate dispenser of justice and a benevolent protector, a tangible representation of legal authority and divine blessing for his subjects.

The Bayeux Tapestry provides a vivid visual record of early medieval royal symbolism, prominently depicting Harold Godwinson enthroned, holding a scepter in his right hand and the orb and cross in his left. This portrayal powerfully illustrates the established iconography of kingship, where the scepter, alongside the orb, served as an unmistakable signifier of sovereign power and legitimacy. Such diverse examples, from ornate shrine-bearing scepters in Scotland to heralds’ protected staffs, underscore the scepter’s deep embedding within the visual and spiritual culture of medieval Europe.

6. **The English Scepters: From Æthelred to Charles II**The historical trajectory of English royal scepters offers a compelling narrative of evolving ceremonial practice and symbolic continuity. Earliest English coronation forms, from the 9th century, already delineate the use of a scepter (*sceptrum*) alongside a staff (*baculum*), highlighting their foundational importance in the investiture of a monarch. The coronation form associated with Æthelred the Unready further specifies a *sceptrum* and a *virga*, a distinction that persists in a 12th-century coronation order, suggesting a consistent, albeit evolving, lexicon of royal insignia within these sacred rituals.

A pivotal moment in the historical record occurs with the contemporary account of Richard I’s coronation. It is here that the royal scepter of gold, conspicuously topped with a gold cross (*sceptrum*), and the gold rod, distinguished by a gold dove at its summit (*virga*), make their inaugural appearance in documented history. This explicit description not only confirms the twin scepter tradition but firmly establishes the iconic symbols of the cross and the dove as integral components of English monarchical identity, symbols that would resonate for centuries.

The meticulous inventory compiled around 1450 by Sporley, a monk of Westminster, provides invaluable detail regarding the relics, including those purportedly used at the coronation of Saint Edward the Confessor. This list explicitly mentions a golden scepter, a wooden rod gilt, and an iron rod, items believed to have been left by the revered king for his successors. These artifacts miraculously survived until the tumultuous Commonwealth period, yet a minute description meticulously drawn up in 1649 tragically precedes their ultimate destruction, marking a profound loss.

The devastation of the Commonwealth era necessitated a complete renewal of the English regalia upon the restoration of the monarchy. For the coronation of Charles II, new scepters bearing the Cross and the Dove were meticulously crafted, echoing ancient traditions. These newly fashioned emblems, though possibly undergoing slight alterations over time, remarkably remain in active use today, underscoring an unbroken thread of royal continuity even through periods of immense political upheaval.

In a further development reflecting the monarchy’s evolving structure, two additional scepters were subsequently introduced for the queen consort. These included one scepter with a cross, mirroring the king’s primary emblem of divine authority, and another with a dove, symbolizing peace and spiritual grace, akin to the king’s secondary scepter. This expansion formally established the queen consort’s distinct, yet complementary, role, ensuring her ceremonial presence was equally adorned with symbols of power and spiritual significance.

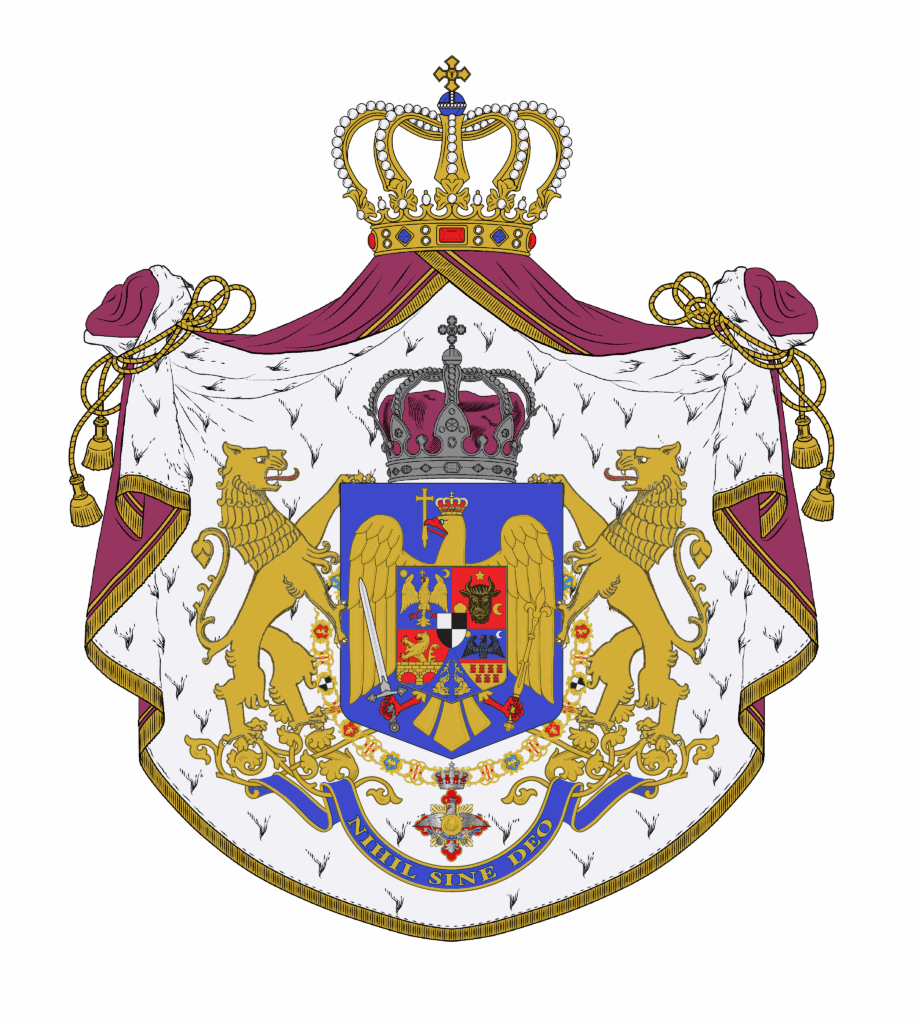

7. **Modern Symbolism: Scepters in Flags and Contemporary Royalty**The enduring resonance of the scepter as a profound symbol of authority and national identity transcends the ceremonial chambers of ancient palaces, finding its way into contemporary state iconography. A remarkable testament to its lasting impact is its incorporation into the designs of national flags, where it continues to project a powerful image of sovereignty. Both Moldova and Montenegro prominently feature scepters on their national banners, typically clasped by eagles. This imagery is not merely decorative; it harks back to ancient imperial traditions, where the eagle symbolized power and dominance, and the scepter, divine right and rulership, thereby embedding a rich historical narrative within modern national emblems.

Beyond national flags, royal scepters continue to play a pivotal, albeit often ceremonial, role in contemporary monarchies around the globe. While the era of absolute monarchical power may have largely receded, the scepter’s symbolic weight remains undiminished in state occasions. For instance, the Royal Sceptre of Boris III of Bulgaria, though belonging to a monarchy that no longer exists, stands as a vivid reminder of the direct connection between regal staffs and the identity of a sovereign, encapsulating the history and aspirations of a nation through its carefully crafted form and embedded symbolism.

Similarly, the grandeur of the Imperial Sceptre held by Emperor Pedro II of Brazil in an 1872 portrait powerfully illustrates its significance in a different royal context. The sheer size and elaborate nature of his scepter, alongside other items of the Brazilian Crown Jewels, underscore the immense wealth, stability, and imperial might that it was intended to convey. Such portraits served not only as artistic renderings but also as potent political statements, using the scepter to project an image of unshakeable authority and dynastic legitimacy to both domestic and international audiences, long after the height of absolute rule.

These regal staffs also continue to be key elements in the coronation ceremonies of existing monarchies, serving as a tangible link to centuries of tradition and continuity. As noted in earlier discussions, the British monarchy, for example, utilizes the Sovereign’s Scepter with Cross, adorned with the legendary Cullinan Diamond, in every coronation since Charles II. This practice vividly demonstrates how scepters, even in an increasingly modern world, continue to embody the continuity of tradition and the solemn transfer of power, acting as a profound anchor for national identity and historical lineage in ever-changing global landscapes.

The enduring relevance of the scepter in contemporary settings extends beyond its physical presence in ceremonies. It continues to influence our collective imagination and understanding of leadership, echoing through historical narratives, and even popular culture. The scepter, in essence, remains a potent cultural artifact, allowing modern societies to connect with the deep roots of governance and the ancient human aspiration for order, justice, and legitimate authority. Its presence, whether on a flag, in a museum exhibit, or during a solemn state event, invariably sparks reflection on the nature of power and the historical forces that have shaped nations.

8. **The Scepter’s Enduring Allure: A Global Perspective**As we journey through the rich history of royal scepters, from the ancient sands of Egypt to the hallowed halls of European monarchies and the profound spiritual traditions of India, one truth consistently emerges: the scepter’s allure is as enduring as its legacy. It stands as a universal emblem, transcending cultural, religious, and political divides, symbolizing the profound human need for legitimate authority, divine sanction, and the visible manifestation of power. This remarkable consistency across millennia speaks to an innate human understanding of leadership, where a tangible staff can articulate immense, often intangible, concepts of governance and sovereignty.

The scepter, in its myriad forms, has always been more than a mere object of adornment; it is a repository of collective memory, a silent witness to countless coronations, decrees, and pivotal moments in history. Whether it represented the ‘shepherd’s crook’ of a benevolent pharaoh, the delegated authority of a Roman imperator, the divine promise to the lineage of Judah, or the ‘just scepter’ (*Sengol*) that bound a Tamil king to his people, each iteration underscores a fundamental principle: that power is not just wielded, but also symbolized, understood, and legitimised through shared cultural artifacts.

Its significance is deeply rooted in its capacity to embody ideals of justice, legitimacy, and continuity. From the *main de justice* in France, symbolizing a king’s role in upholding law, to the scepters with the cross and the dove in England, representing both temporal and spiritual guidance, these staffs have served as potent visual catechisms of governance. They remind us that the authority to rule is often intertwined with a perceived moral or divine mandate, an expectation that leaders will not merely command, but also serve, protect, and guide their populace with wisdom and equity.

Even in an era where many monarchies are constitutional and their rulers largely symbolic rather than absolute, the scepter retains its profound cultural resonance. The recent re-installation of the *Sengol* in the Indian Parliament, for instance, dramatically illustrates how ancient emblems can be re-contextualised to signify modern national identity and historical continuity, sparking contemporary debates about their meaning and legacy. Such instances highlight the power of these artifacts to bridge vast historical spans, connecting present-day governance with ancestral traditions and imbuing national narratives with a deep sense of heritage and purpose.

Ultimately, the allure of royal scepters lies in their timeless ability to communicate the essence of sovereignty. They are artifacts that speak volumes without uttering a single word, conveying centuries of history, philosophy, and cultural values in their design, their materials, and their very presence. As long as societies ponder the nature of leadership and the transfer of power, the scepter, in its iconic magnificence, will continue to captivate our imagination, serving as an enduring symbol of humanity’s quest for order, justice, and the profound responsibilities that come with holding the reins of authority.