Let me tell you something wild – when I first started looking into electric vehicles, I thought the hardest part would be the upfront cost. Boy, was I wrong! It turns out, the journey from showroom to daily driver is packed with financial surprises that can catch even the most prepared buyer off guard. These aren’t just small bumps in the road; they’re financial detours most people simply don’t see coming.

Electric vehicles are indeed awesome. They are clean, increasingly efficient, and let’s be honest, they just look cool. There’s a lot of hype, and it’s easy to get caught up in the excitement of lower fuel costs and a smaller environmental footprint. However, focusing solely on those benefits can lead to a less informed path when estimating the actual cost of daily ownership.

While the industry forecasts significant sales growth, with 1 million new EVs expected to be sold in the United States in 2023, doubling 2021’s volume, it’s crucial to understand the full financial picture. We’re here to dive more deeply into the many factors contributing to the costs of electric car daily ownership, exposing as many cost surprises as possible to help you create and follow a realistic budget. This guide will pull back the curtain on those sneaky expenses, providing practical insights on what electric vehicle ownership truly costs.

1. **The Higher Sticker Price**One of the most immediate financial realities for prospective EV owners is the sticker price. On average, new electric vehicles cost more than those with internal combustion engines. According to data from Cox Automotive, the average cost of a new ICE vehicle was $48,528 in May 2023, while the average electric vehicle stood at $55,488. This is before factoring in any government rebates or incentives, though a full $7,500 tax credit could potentially bridge some of that gap.

When looking at specific models, the disparity becomes even clearer. For example, comparing entry-level trims of the Hyundai Kona versus the Hyundai Kona Electric, the EV version costs $11,410 more. Similarly, the Volvo XC40 Recharge costs $17,000 more than its gasoline-fueled counterpart, the XC40. While EVs often come with more features, leading to not quite an apples-to-apples comparison, even after adjusting for feature differences (e.g., an estimated $8,558 for Kona and $12,750 for the XC40), the EV transaction prices remain higher.

This higher upfront cost means you’ll either need to put more money down initially or finance a larger balance. This translates directly to higher monthly payments for the average EV compared to the average ICE vehicle. While electric car prices have shown a steady tumble, down more than $10,000 on average in the past year, the initial investment remains a significant financial hurdle that many buyers aren’t fully prepared for.

2. **Home Charging Setup Costs**One of the biggest benefits of owning an electric vehicle is the potential for significant savings on fuel costs by charging at home. Powering your vehicle at the same rate as household electricity can indeed be far more cost-effective than repeatedly paying for gasoline. However, this convenience often comes with an unforeseen upfront investment in additional infrastructure.

Most homes are not pre-equipped with an EV charger, meaning owners must invest in installing a suitable charging station. While a basic Level 1 charger, often included with most EVs, is adequate for smaller capacity batteries like those in plug-in hybrids, it’s impractical for larger EV batteries, potentially taking up to 36 hours for an 80% charge. Recognizing that home charging is generally cheaper than commercial options, many EV owners quickly realize the wisdom, and necessity, of investing in a Level 2 home charger.

Owning and installing a Level 2 charger can carry a hefty price tag. Portable Level 2 chargers can start around $200, but a permanent system in your garage can cost up to $1,000 for the unit itself. Professional installation, essential for safety and efficiency, can range from $400 to $3,400. This wide price spread is due to the requirement of a 240V power source, similar to what a clothes dryer uses, which may necessitate running a new electrical line to the appropriate location. It’s always wise to ask a professional to evaluate your electrical system beforehand to determine the availability of a 240V source and the associated costs, though state and utility company incentives can sometimes help offset these expenses.

3. **Public Charging Expenses**Public charging is a major consideration for many EV owners, especially as range anxiety remains a significant issue. While the network of public chargers is expanding, their accessibility, efficiency, and costs can still fall short of the convenience offered by traditional gas stations. Relying on these stations can introduce both financial and time-related frustrations.

One challenge EV owners face is compatibility, particularly with older EVs that may not support Tesla’s North American Charging Standard, requiring the purchase of adapters costing up to $250. Beyond compatibility, the speed and cost of public charging vary widely. Level 2 public chargers, while generally more affordable per kilowatt-hour than gasoline, can take around an hour to recharge a battery to 80%. Many drivers find these lengthy wait times frustrating, with a 2024 J.D. Power survey revealing that less than half of EV owners are satisfied with public Level 2 charging.

For those seeking faster replenishment, DC Fast Charging can get a battery up to 80% in under 25 minutes. However, this convenience comes at a significant cost, with prices often reaching nearly 50 cents per kilowatt-hour. In some areas, this can be comparable to, or even more expensive than, filling up a gasoline tank. While improvements are being made to public charging experiences, the need to rely on public stations can still be a drawback of EV ownership, demanding either extra time or additional expense.

4. **Fluctuating Electricity Costs**Just as the price per gallon of gasoline fluctuates, so do electricity rates, and this can significantly impact the operational cost of your EV. A March 2023 article in Forbes highlighted that electricity costs had surged across the United States, with some areas, particularly the Northeast, experiencing price jumps as high as 57% from January 2021 to January 2023. This trend is predicted to continue, meaning your monthly charging costs can be subject to unexpected increases.

To accurately budget for your EV’s energy consumption, a bit of math is required. Start by locating your latest electric bill to determine your cost per kilowatt-hour (kWh) by dividing the total kWh used into the bottom-line total. For instance, the average cost for U.S. households is about 16 cents per kWh. Next, estimate your average monthly mileage; the national average in 2021 was 1,124 miles. Most experts suggest an EV gets 3 to 4 miles of range from one kWh, and it’s advisable to use a conservative estimate of 3 miles per kWh for budgeting.

With these numbers, you can calculate your approximate monthly cost: divide your monthly mileage by 3 to determine the kWh required, then multiply that by your cost per kWh. For example, 1,124 miles divided by 3 miles/kWh equals 375 kWh, which at 16 cents/kWh results in an approximate monthly cost of $60 to charge your electric car. While this often compares favorably to gasoline costs—the EPA estimates annual charging for a Kona Electric at $600 versus $1,700 for a gasoline Kona—the variability of electricity rates means this isn’t a fixed saving and requires ongoing attention.

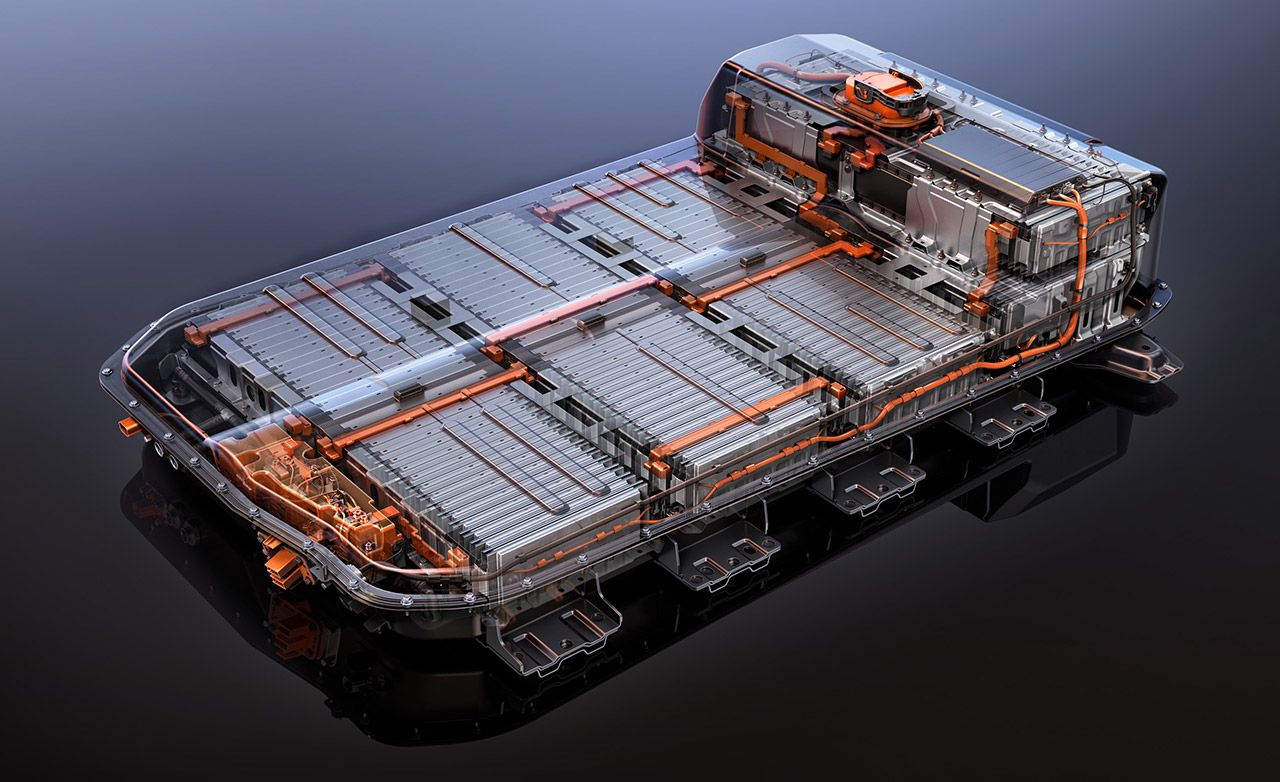

5. **Battery Degradation and Replacement**The specter of electric vehicle battery replacement costs is a frequently cited concern for those considering an EV, and it’s a fear not entirely without merit. Replacement costs remain historically high; J.D. Power reported that the average cost of replacing a Tesla Model S, Model X, or Model 3 battery could be at least $13,000. To put that in perspective, a 2023 Model 3 costs around $40,240, meaning the battery alone accounts for about 30% of the total vehicle price. This highlights that the battery is a significant, if not the primary, contributing factor to an EV’s overall cost.

However, there is a silver lining in the realm of battery replacement: most occurrences happen under warranty. The federal government mandates that EV battery warranties cover at least eight years or 100,000 miles, with some carmakers offering even longer periods. Furthermore, California’s regulations, which often set a precedent, will require EV batteries to retain at least 70% of their range for 10 years or 150,000 miles starting with the 2026 model year, increasing to 80% for 2030 models and beyond. Experts also suggest that an electric car battery may last up to 20 years, with tracking companies like Recurrent and GeoTab finding that most EV batteries degrade around 2.3% per year.

Despite the robust warranties, battery degradation is an inherent part of their lifecycle, meaning an aging battery will gradually lose some of its charging capacity. Instead of holding a 100% charge, it might only reach 90% or 80% over time, leading to more frequent recharges and reduced range—an extra cost in both money and time. Environmental factors also play a role: both extreme hot and cold temperatures can significantly reduce an EV’s range and increase charging times. Additionally, frequent use of DC fast chargers and consistently filling a battery to 100% capacity can hasten this loss of charging capacity, which is why carmakers often recommend charging to only 80% at fast chargers.

6. **Accelerated Depreciation and Residual Value**Depreciation is an unavoidable reality for all vehicles, but for electric vehicles, it can be an unexpectedly large hidden cost. Residual value, which measures the value lost over a specified number of years, often shows ICE vehicles holding an advantage over EVs. Data from Cox Automotive’s depreciation tracking tools consistently bears this out, and while the differences aren’t always significant, in many cases, they are considerable.

Consider the comparison between the Hyundai Kona and the Kona Electric. Over five years, the Kona Electric is projected to depreciate by $28,210, whereas the gasoline-fueled Kona depreciates by $12,980. This represents a substantial difference of $15,230, which is a massive hidden expense that impacts your long-term financial picture. Similarly, the Volvo XC40 loses $21,939 in value over five years, while the XC40 Recharge depreciates by $30,955 during the same period, giving the ICE XC40 a depreciation advantage of $9,016.

Several factors contribute to this accelerated depreciation. The rapid advancements in EV technology can quickly make older models less desirable. Furthermore, the decreasing sticker price of newer EVs makes older models less attractive in the used market. Government incentives, such as the $7,500 federal tax credit for new EVs, also play a role; since used EVs don’t always qualify for such breaks, they become less appealing to shoppers, intensifying their depreciation relative to their original MSRP. While this rapid loss in value is a disadvantage for original owners, it paradoxically creates an excellent opportunity for buyers in the used EV market, allowing them to find low-mileage models at significantly reduced prices.

Navigating the electric vehicle landscape means understanding that the financial journey extends far beyond the initial purchase and basic charging. As we peel back another layer, we discover a set of ongoing expenses that might not be as immediately apparent but are crucial for any prospective EV owner to consider for a complete and realistic budget.