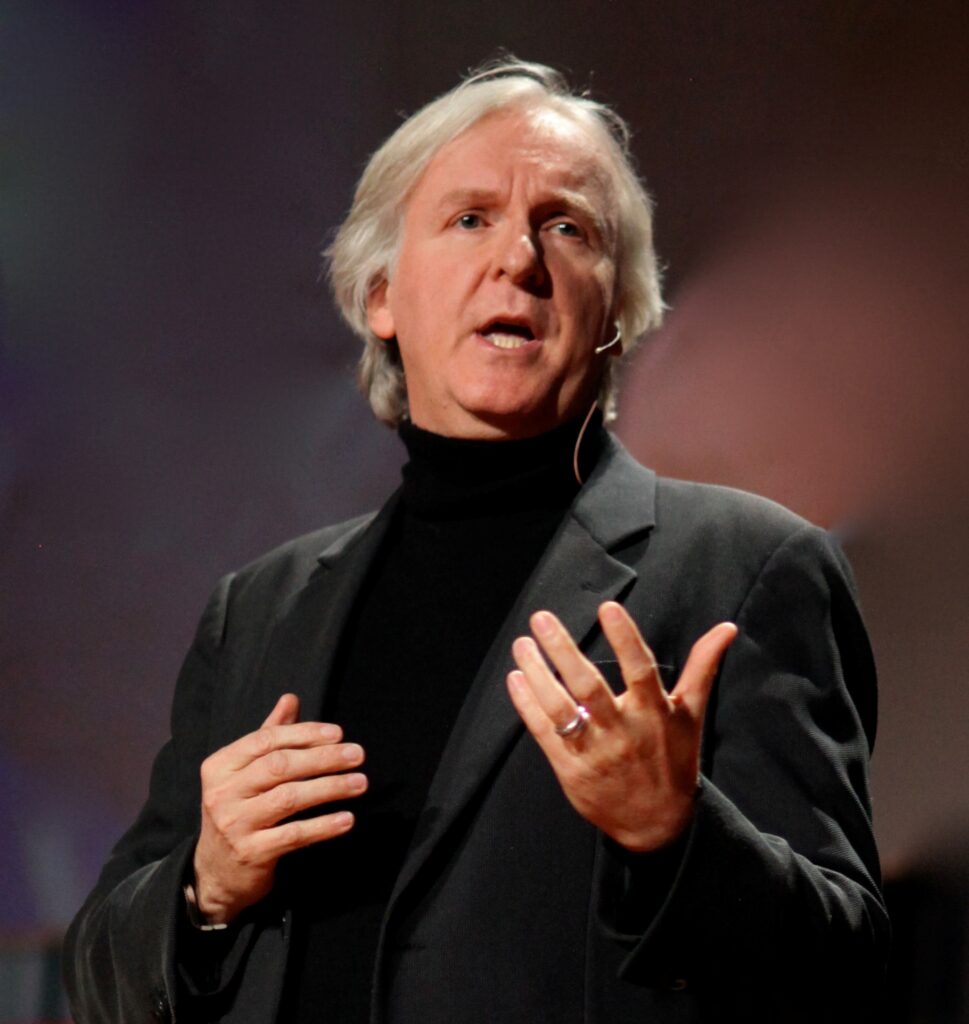

James Cameron stands as a cinematic titan, his name synonymous with pushing boundaries, both technological and narrative. His career, built on audacious risks and consistently helming the most expensive films, has repeatedly seen him emerge victorious at the box office. With three of the four highest-grossing titles ever, his acumen for captivating audiences is undeniable, solidifying his reputation as a visionary who rarely backs down.

However, even formidable figures have moments of introspection. For James Cameron, one particular narrative decision in his epic masterpiece, “Titanic,” has become a lingering point of regret. It’s a scene involving First Officer William Murdoch, whose portrayal sparked significant backlash, compelling Cameron to issue a public apology – a strikingly uncharacteristic move for a director known more for telling detractors to “go themselves.” This rare humility offers a compelling case study.

This article delves deep into this singular remorse, dissecting the layers behind Cameron’s regret, the historical inaccuracies that fueled controversy, and the profound impact on the real individuals whose lives were dramatized. We explore specific cinematic choices, examine historical records, and consider broader implications for filmmakers navigating the delicate balance between artistic license and fidelity to historical truth. Our aim: to understand not just *what* Cameron regretted, but *why* it indelibly marked an otherwise triumphant career.

1. **James Cameron’s Unyielding Reputation and Rare Apology**James Cameron’s Hollywood journey is often painted with strokes of uncompromising vision and superhuman resolve. He is renowned as one of cinema’s hardest taskmasters, making enemies and subjected to “more lawsuits than the average auteur.” Yet, he consistently emerges “smelling of roses,” transforming colossal financial bets into astronomical successes. This pattern of unyielding conviction has forged an image of a director impervious to criticism and steadfast in his artistic decisions.

His career is a testament to this audacious approach, building an empire on continuously innovating and “pushing the boundaries of technology to new heights.” This risky strategy has undeniably “paid off handsomely,” evidenced by his directorial hand in “three of the four highest-grossing titles to ever grace the silver screen.” Such a formidable resume reinforces the perception that Cameron dictates the narrative, rarely conceding ground or expressing public remorse.

It is precisely this persona that makes his apology regarding First Officer William Murdoch’s portrayal so profoundly significant. For a director who “has never come across as a person who’ll backtrack on anything they’ve said or done,” and who is “a lot more likely to tell his detractors to go themselves,” admitting he was wrong was a watershed moment. This rare admission provides a window into the intense pressures and ethical dilemmas inherent in adapting real-life tragedies for the big screen.

Read more about: Why James Cameron Still Grapples with One Major Regret from His Magnum Opus, ‘Titanic’

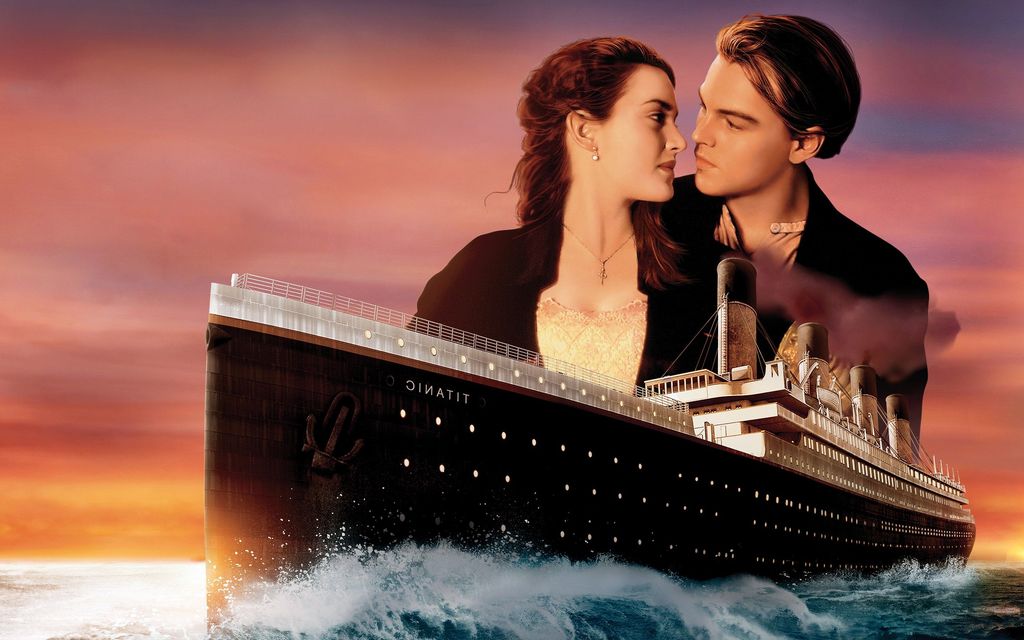

2. **The Factual Gaps in the Controversial Scene**The scene at the heart of James Cameron’s regret is undoubtedly one of “Titanic’s” most dramatic and harrowing sequences. As panic grips passengers vying for scarce lifeboat spots, First Officer William Murdoch, portrayed by Ewan Stewart, takes drastic and tragic action. He is shown shooting “two passengers in a moment of panic as all hell breaks loose aboard the ship before turning the gun on himself and committing suicide.” His body “floating face down in the water,” a grim end.

Cameron’s decision to include this depiction was not entirely baseless; he stated he “based this scene on eyewitness evidence of a shooting/suicide by an officer during the launching of the lifeboats from the actual Titanic.” Indeed, “multiple survivors claim that there was a shooting while Collapsible C was being loaded.” This provides a kernel of historical context, suggesting dramatic events involving an officer, a gun, and desperate measures did occur generally.

However, the crucial factual gap lies in attributing these actions specifically to William Murdoch. While “eyewitness accounts claimed there was an officer who shot themselves on the Titanic,” the context explicitly states “there’s no confirmation as to whether or not it was Murdoch.” Accounts like George Rheims’ and Eugene Daly’s described an unnamed officer. Hugh Woolner, the only eyewitness who “claimed that William Murdoch had a pistol,” described him firing “a pistol in the air.” Woolner “never claims that Murdoch shot a passenger or killed himself.” Thus, the definitive link to Murdoch was a creative embellishment for dramatic impact, not a confirmed historical fact.

Read more about: Skip the Stream: 5 Biographical Films So Off-Key, Even Their Subjects Couldn’t Stomach the Story.

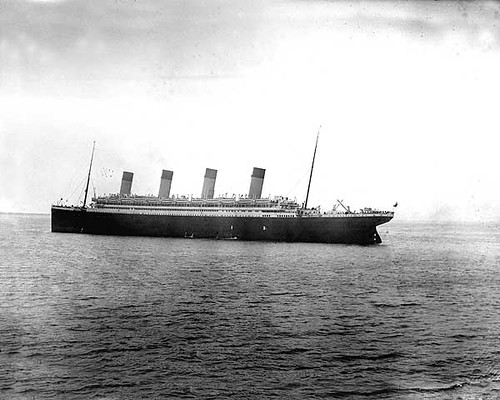

3. **First Officer William Murdoch: A Real-Life Hero’s Legacy**The cinematic portrayal of First Officer William McMaster Murdoch as a panicked officer committing murder-suicide stands in stark contrast to historical consensus. In real life, Murdoch was largely regarded as a heroic figure, particularly in his hometown of Dalbeattie, Scotland, where a memorial was erected. This disconnect fueled the controversy.

Eyewitness reports frequently depict Murdoch exhibiting exemplary conduct under unimaginable pressure. He was placed “in charge of boats on the ship’s starboard side” during the evacuation, a role he executed with diligence and a pragmatic approach to saving lives. While adhering to “women and children first” protocol, he also “allowed men to fill up any extra space leftover in lifeboats,” maximizing survival rates.

Furthermore, historical records largely exonerate Murdoch from blame for the catastrophe. The “British Titanic Inquiry later concluded that Murdoch was not to blame for the sinking,” reinforcing his competence and integrity. Unlike the film’s suggestion of him being “overcome by guilt” for “helming the ship” into the iceberg, inquiries found no such culpability. His body, tragically, “was never recovered,” adding to the somber legacy of a man who served his duty until the end.

4. **The Profound Outcry from Murdoch’s Family and Hometown**The release of James Cameron’s “Titanic” ignited a furious and deeply personal backlash from the family and hometown of First Officer William Murdoch. For Dalbeattie, Scotland, where Murdoch was a revered native son, the cinematic depiction of him as a murderer and suicide victim was not merely fictional liberty; it was a profound insult to his memory and a source of immense grief for his descendants. This visceral reaction underscored the real-world consequences of dramatic portrayals.

The family’s distress was immediate and sustained. William Murdoch’s nephew, Scott Murdoch, became a prominent voice, telling BBC News in 1998 that his uncle “didn’t commit suicide” and emphasizing that “If someone says to you somebody committed suicide when he hadn’t you take objection.” This wasn’t just historical inaccuracy but a direct challenge to the family’s understanding of their ancestor’s honorable death. They maintained Officer Murdoch “did everything he could to save lives,” contradicting the film’s narrative.

The intensity of the family’s objection eventually compelled Paramount Pictures to take an extraordinary step. Studio vice president Scott Neeson journeyed to Dalbeattie to “issue a personal apology,” stating the movie “never intended to portray him as a coward.” This highly unusual gesture highlighted the severity of the offense and the tangible harm inflicted. However, even this direct outreach did not fully quell the indignation, as Murdoch’s nephew remained “indignant that Titanic would ‘still portray my uncle as a murderer when he was a hero and helped save many passengers.'”

The sustained pressure from Murdoch’s family, who “had contacted the director multiple times,” ultimately led to James Cameron’s public apology in 2004. Their unwavering commitment to defending their ancestor’s honor played a crucial role, demonstrating the moral responsibility filmmakers carry when weaving narratives around real people whose legacies are cherished by living relatives. The outcry from Dalbeattie and the Murdoch family served as a potent reminder that cinema does not exist in a vacuum from historical truth and personal sensitivities.

5. **Cameron’s Candid Admission: Storyteller vs. Historian**In the wake of significant backlash, James Cameron offered a remarkably candid explanation for his creative choices, highlighting the tension between storyteller and historian roles. His defense, while acknowledging harm, revealed the thought process of a filmmaker driven by narrative imperatives. He admitted he “took the liberty of showing him shoot somebody and then shoot himself,” explaining that as a “named character; he wasn’t a generic officer.”

Cameron described his screenwriter’s internal dialogue: “‘Oh, the guy who is responsible for helming the ship, on his watch, he’s the one who essentially ran the ship into an iceberg. Was he overcome by guilt? Was he trying to save as many people as he could but when the riot broke out he overreacted?’ Who knows,” he explained. This showcases how he “start[ed] connecting the dots” to create a compelling, tragic arc, attributing motivations and actions to Murdoch not definitively supported by fact. He saw Murdoch as carrying “all this burden with him,” which “made him an interesting character.”

Crucially, Cameron later acknowledged the flawed premise of this singular focus on dramatic impact. “I think I got a little carried away with the narrative and was not sensitive to the impact that it might have had on the families,” he confessed. This realization underscored a fundamental ethical responsibility he overlooked. He articulated this: “And this is the responsibility that one carries when you’re making what’s essentially a big docudrama because you’re telling the story of something that really happened, and I did populate it with real people.”

6. **The “Unchangeable” Scene: Why No George Lucas-like Alterations?**Despite James Cameron’s profound regret and his acknowledgment of inaccuracies in First Officer William Murdoch’s depiction, the contentious scene remains an immutable part of “Titanic.” This raises a question: why, in an age of special editions and director’s cuts, has Cameron not exercised his influence to modify or remove it? The answer, he explained, lies in the deep structural integration of the sequence within the film’s elaborate narrative.

Cameron explicitly stated that the scene is “too deeply woven into the story for Cameron to make any George Lucas-like alterations in subsequent versions.” This comparison to George Lucas, infamous for “Star Wars” revisions, is telling. It suggests that unlike minor digital enhancements, the Murdoch sequence is fundamentally tied to “Titanic’s” emotional and dramatic progression. It serves as a pivotal moment of escalating chaos, demonstrating the raw panic and moral compromises that defined the ship’s final hours, directly impacting other characters.

The scene’s function extends beyond merely illustrating Murdoch’s demise. It contributes to the overall sense of desperation and collapse of order, crucial for conveying the tragedy’s magnitude. Removing or altering it would likely necessitate re-editing substantial portions, potentially disrupting pacing, character development, and established emotional beats. Such a task would be far more involved than a simple cut, requiring a partial re-imagining of the film’s third act—a daunting and perhaps artistically undesirable prospect for a completed work of such renown.

Once a film achieves global iconic status, its scenes, even controversial ones, become ingrained in collective consciousness. The “Titanic” scene involving Murdoch is widely known, making any alteration an act of revisionism that could spark further debate. Cameron’s decision to leave it intact, despite regrets, underscores practical and artistic limitations once a major work is released. The apology, in this context, serves as the only viable corrective action, an acknowledgment of error that cannot be undone on screen.

7. **Actor Ewan Stewart’s Reflections on Portraying Murdoch**The intricate ethical considerations of depicting real historical figures extend beyond the director’s chair, often reaching the actors who embody these roles. Ewan Stewart, the actor who brought First Officer William Murdoch to life on screen, also found himself reflecting on the weight of his portrayal in the aftermath of the film’s immense success and the ensuing controversy. His personal introspection adds another layer to the complex dialogue surrounding historical accuracy in cinematic adaptations.

Stewart candidly admitted to a certain lack of initial foresight regarding the full implications of his role. “I’m ashamed to say it, really, now — I hadn’t really given that a lot of thought, that I was playing a real person,” he confessed. This revealing statement highlights how, in the intense process of filmmaking, the focus on performance and narrative can sometimes overshadow the deeper historical and ethical responsibilities involved when the character is drawn from life, rather than pure imagination.

His admission underscores a crucial point for all involved in such productions: the portrayal of real individuals carries a profound responsibility. An actor’s performance, no matter how compelling, can indelibly shape public perception of a historical figure, especially when that figure is part of a grand narrative presented to millions. Stewart’s honest reflection serves as a reminder that even for those in front of the camera, the balance between dramatic license and historical fidelity is a delicate and often learned lesson.

8. **The Ethical Responsibilities of ‘Docudrama’ Filmmaking**The controversy surrounding William Murdoch’s depiction casts a harsh, yet necessary, spotlight on the inherent ethical responsibilities that accompany “docudrama” filmmaking. James Cameron himself articulated this burden, recognizing that when a film blends historical events with dramatic narrative, the impact on real people and their legacies becomes a paramount concern. It is a genre that demands a unique blend of artistic vision and historical conscience.

Cameron reflected on this, stating, “This is the responsibility that one carries when you’re making what’s essentially a big docudrama because you’re telling the story of something that really happened, and I did populate it with real people.” This statement is critical, acknowledging that once actual names and events are woven into a fictionalized plot, the film transcends mere entertainment to become a public record, influencing collective memory and potentially causing real-world harm.

Indeed, crafting a work of fiction based on a real historical event presents a unique set of challenges. Many individuals within such narratives were real people, and their living relatives may not be pleased with how their ancestors are portrayed. Even minor inaccuracies, which most viewers might overlook, can become significant problems, as evidenced by the “Queen’s Gambit” lawsuit over a throwaway line. For a monumental tragedy like the “Titanic,” where figures faced impossible choices, an inaccurate portrayal can ignite a far more substantial and prolonged backlash.

Unlike purely fictional characters such as Jack and Rose, whose narratives exist solely within the film’s imaginative confines, characters drawn from history carry a pre-existing identity. Filmmakers, therefore, must tread carefully, understanding that their creative choices can deeply affect how a historical figure is remembered, often for generations. This intricate dance between artistic freedom and historical accuracy forms the very ethical bedrock of docudrama.

Read more about: Why James Cameron Still Grapples with One Major Regret from His Magnum Opus, ‘Titanic’

9. **The Parallel Controversy: J. Bruce Ismay’s Portrayal**While much attention has rightly focused on First Officer Murdoch, “Titanic” also drew considerable criticism for its portrayal of another real-life figure: J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman and managing director of the White Star Line. Portrayed by Jonathan Hyde, Ismay emerges as a far less sympathetic character, embodying a different kind of controversial dramatization that raises similar questions about historical fidelity. His depiction sparked a parallel, albeit less publicly discussed, debate.

Early in the film, Ismay is depicted arrogantly pressuring Captain Smith to increase the ship’s speed, implying that his hubris directly contributed to the disaster. Later, during the chaotic evacuation, he is shown sneaking onto a partially filled lifeboat, explicitly stated to be “meant for women and children,” under the disapproving gaze of an officer. This cinematic sequence frames him as a self-serving individual, more concerned with his own survival than the lives of the passengers entrusted to his company’s care.

However, historical accounts present a more nuanced, and often contradictory, picture. There is little concrete evidence to suggest Ismay ever pressured Captain Smith to sail faster, or that the captain would have even heeded such a demand. Furthermore, numerous first-hand accounts from others on the lifeboat Ismay boarded attested that there were no women and children nearby at the time, and that he was explicitly ordered by an officer to get into the boat to fill available space. These historical discrepancies profoundly challenge the film’s villainous narrative.

The film’s approach to Ismay, while clearly negative, also invites a degree of viewer introspection. The scene appears to ask, “would you not be tempted to do the same thing in his situation?” Yet, despite this implicit question, Ismay “still doesn’t come off well,” leaving audiences with an image of a man whose hubris led to thousands of deaths, while he selfishly secured his own escape. This portrayal, while dramatically potent, significantly diverged from historical records, much like Murdoch’s.

10. **The Curious Lack of Apology for Ismay’s Depiction**A striking aspect of the “Titanic” controversies is the stark contrast in how the production handled the backlash concerning William Murdoch versus J. Bruce Ismay. While James Cameron and Paramount Pictures eventually issued apologies and acknowledged regret regarding Murdoch’s portrayal, no such public statement or expression of remorse has been extended for the depiction of Ismay. This disparity prompts reflection on the factors that might drive such different responses to historical grievances.

The absence of an apology for Ismay’s characterization is particularly noteworthy given the considerable liberties taken with his historical actions. His cinematic depiction as both an instigator of the disaster and a coward during the evacuation is arguably as significant a distortion as Murdoch’s murder-suicide. Yet, the fervent and sustained pressure from Murdoch’s family, who directly contacted the director multiple times, appears to have been a crucial catalyst for Cameron’s eventual admission of error.

Perhaps the relative lack of organized familial outcry from Ismay’s descendants played a role, or perhaps his historical image was already less universally heroic than Murdoch’s, making his cinematic villainy more palatable to the broader public. Murdoch, in his hometown of Dalbeattie, was revered as a hero, making his on-screen vilification a direct attack on a cherished legacy. Ismay, conversely, had already faced public scrutiny and blame in the immediate aftermath of the sinking, which may have lessened the perceived need for a cinematic defense or apology.

Regardless of the underlying reasons, the differing responses highlight the complex interplay of public perception, historical context, and the intensity of familial advocacy in shaping a filmmaker’s accountability. It suggests that while historical accuracy is a general principle, the practical impetus for correction often comes from persistent, personal appeals. For Ismay, that sustained advocacy, at least publicly, did not materialize to the same degree as it did for Murdoch.

11. **The Suggestion of Fictionalizing Real Characters’ Names**The enduring controversies surrounding “Titanic’s” historical portrayals, particularly those of Murdoch and Ismay, have led to a compelling suggestion: perhaps filmmakers should consider fictionalizing the names of real characters in docudramas. This approach could offer a viable pathway to maintaining dramatic license without incurring the “moral problems” that arise from inaccurately depicting actual historical figures and distressing their living descendants.

Changing the names of these individuals would effectively create characters “loosely based on real people” rather than presenting them as definitive historical representations. This clear distinction would allow creative freedom to craft compelling narratives and explore thematic elements without falsely attributing specific, often damaging, actions or motivations to real historical figures. The implicit understanding would be that while inspired by history, the characters are ultimately fictional constructs.

Such a strategy has precedent within the film itself. The central protagonists, Jack Dawson and Rose DeWitt Bukater, are entirely fictional characters, and “no one cared that Rose nor Jack were not real people.” Audiences readily accept these fictional insertions into a historical backdrop. By extending this principle to other non-protagonist figures, filmmakers could avoid the direct ethical dilemmas of misrepresenting historical identities, while still grounding their story in the factual context of the event.

While some might argue that viewers should ideally understand that “this is all a dramatization of events not meant to be taken as total fact,” such a defense becomes increasingly tenuous when a film, like “Titanic,” takes “meticulous steps to ensure historical accuracy” in numerous other regards. This commitment to verisimilitude elsewhere makes it challenging for families to accept the “it’s just fiction” argument for deeply offensive characterizations. Fictionalizing names offers a potential middle ground, allowing for artistic license without sacrificing the integrity of personal legacies.

12. **Overarching Lessons: Balancing Artistic Vision with Historical Fidelity**The indelible regret expressed by James Cameron concerning First Officer William Murdoch’s portrayal ultimately transcends the specifics of one scene; it encapsulates broader, enduring lessons for all filmmakers navigating the treacherous waters of historical adaptation. It highlights the profound and often overlooked responsibility that comes with transforming real human tragedy into cinematic spectacle, underscoring the delicate balance between artistic vision and historical fidelity.

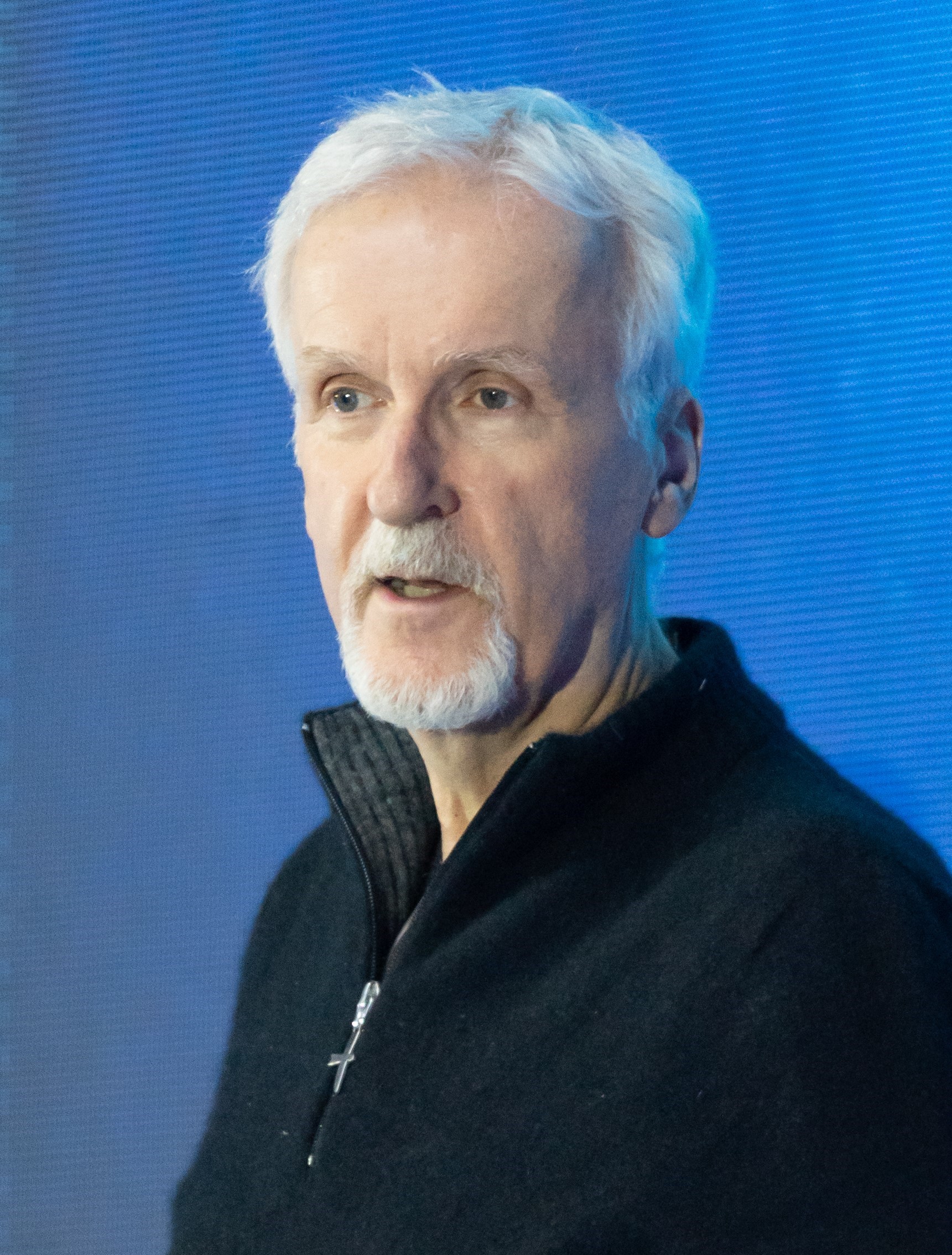

Cameron’s journey from a “storyteller” who got “carried away with the narrative” to an individual who realized the importance of being “sensitive to the impact that it might have had on the families” is instructive. His admission, “I think I have come to the realization that it was probably wrong to portray a specific person, in this case First Officer Murdoch, as the one who fired the weapon,” demonstrates an evolution in understanding the moral weight of his craft. He has since performed “extensive research not only on the Titanic itself but the victims of the ill-fated liner,” suggesting a deeper engagement with historical truth.

Had he “to make Titanic again,” Cameron stated he “would have stayed much closer to the facts when dealing with a real-life character.” This reflection speaks volumes about the lasting impact of the controversy. It reinforces the idea that while dramatic narratives demand conflict and resolution, these must be carefully weighed against the real-world consequences for the individuals and their descendants whose lives are being depicted. The “responsibility that one carries” in a docudrama is not merely to entertain, but to honor or, at the very least, not to defame.

The “Titanic” case serves as a powerful cautionary tale, demonstrating that cinematic masterpieces, even those lauded for their meticulous attention to detail, can stumble when personal histories are treated as mere plot devices. It stands as a testament to the enduring power of family memory and the ethical imperative for filmmakers to approach the stories of real people, especially in the context of tragedy, with profound respect and unwavering commitment to verified fact. The pursuit of dramatic intensity must never fully overshadow the solemn duty to historical truth.

As the curtains draw on this deep dive into James Cameron’s profound regret, the “Titanic” saga offers far more than just a glimpse into a director’s introspection. It unfurls a rich tapestry of considerations for an industry constantly seeking to blend entertainment with reality. From the nuanced ethical tightrope of docudrama to the lasting echoes on family legacies, the story of First Officer Murdoch’s portrayal reminds us that cinema’s immense power to captivate also carries an equally immense responsibility. It’s a striking lesson, etched into one of the most successful films ever made, urging us all—creators and audiences alike—to reflect more deeply on the human stories behind the spectacle, ensuring that in our quest for compelling narratives, we never lose sight of the profound truths they represent.