In the annals of justice, or what some might term retribution, humanity has long sought methods of execution that are both effective and, increasingly, perceived as humane. This quest, steeped in complex ethical and practical considerations, has led to the widespread adoption of a particular procedure that, by its very design, functions as the ultimate ‘lethal weapon’ in the state’s arsenal: lethal injection.

While its intent was to supplant older, more visibly brutal forms of capital punishment, lethal injection has itself become a focal point of intense debate and scrutiny. Touted as a more compassionate alternative, its implementation has unveiled a litany of complications, ethical quandaries, and legal battles that challenge its very premise of a painless and dignified death. This method, once heralded as a sign of progress, now stands at a crossroads, its efficacy and humanity perpetually questioned.

This article embarks on an in-depth exploration of lethal injection, moving beyond its procedural facade to examine its historical roots, its intricate pharmacological mechanisms, and the profound controversies that define its modern application. We will dissect the elements that comprise this ‘lethal weapon,’ understanding its journey from a theoretical concept to the globally utilized, yet deeply contested, practice it is today.

1. **Defining the ‘Lethal Weapon’: The Core Mechanism of Lethal Injection**Lethal injection is, at its most fundamental, the deliberate act of introducing one or more drugs into a person’s bloodstream with the explicit goal of inducing death. This procedure, now synonymous with capital punishment, primarily employs a cocktail of substances—typically a barbiturate, a paralytic, and potassium—to achieve its fatal outcome.

While its main application resides within the realm of capital punishment, the term “lethal injection” can also extend, in a broader sense, to encompass practices such as euthanasia and other forms of medically assisted suicide. In all these contexts, the precise administration of these compounds is designed to bring about a terminal state with a specific physiological sequence.

The sequence of effects orchestrated by these drugs is meticulously planned to ensure, in theory, a swift and irreversible progression. First, the individual is rendered unconscious, a critical step intended to prevent awareness of the subsequent stages. Following this, the drugs are designed to halt the person’s breathing, leading to asphyxiation, before ultimately inducing a heart arrhythmia that culminates in cardiac arrest.

This deliberate, multi-stage physiological shutdown underscores the calculated nature of lethal injection, embodying a modern yet contentious approach to the solemn act of ending a life. It is a system designed for a singular, irreversible purpose, functioning as a highly specialized and controlled ‘lethal weapon.’

2. **A Grim History: From 19th Century Concept to Nazi Atrocity**The notion of a lethal injection as a means of execution first surfaced on January 17, 1888, when New York doctor Julius Mount Bleyer proposed it. His rationale was strikingly pragmatic, praising the method for being “cheaper than hanging,” highlighting a century-old drive for efficiency in capital punishment.

Bleyer’s visionary, albeit chilling, idea lay dormant for decades, only to be revived in the mid-1970s within the United States. This resurgence was largely spurred by growing public disapproval of electrocutions, which were increasingly marred by a series of botched executions, prompting a search for a method perceived as more humane and less grotesque.

Tragically, the most infamous early implementation of lethal injections occurred during World War II, under the horrifying auspices of Nazi Germany. The Nazi regime systematically employed this method to execute prisoners as part of its Action T4 euthanasia program, spearheaded by Karl Brandt, targeting what it deemed “Lebensunwertes Leben” (“life unworthy of life”). Moreover, lethal injections were administered to children detained at the Sisak concentration camp by its physician-commander, Antun Najžer, adding another dark stain to its early history.

Post-war, the method was considered by the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment in Britain between 1949 and 1953. However, it was ultimately ruled out, largely due to intense pressure from the British Medical Association (BMA), underscoring early ethical objections from the medical community regarding physician involvement in executions.

3. **The American Adoption: Oklahoma, Texas, and the Rise of a New Execution Method**The United States took a decisive step towards modernizing its execution protocols when, on May 10, 1977, Oklahoma became the first state to officially approve lethal injection. This landmark decision came after Governor David Boren signed a bill into law, a legislative effort notably introduced by Episcopal Reverend Bill Wiseman, signifying a societal shift in how capital punishment was envisioned.

Remarkably, the very next day, Texas, another prominent state in the death penalty landscape, followed suit. It quickly passed its own lethal injection law, illustrating a rapid consensus and eagerness among states to embrace what was then considered a more progressive and humane method of execution.

This early adoption by Oklahoma and Texas set a powerful precedent, leading to widespread acceptance across the nation. By 2004, an astonishing 37 of the 38 states then utilizing capital punishment had introduced lethal injection statutes. Nebraska, initially maintaining electrocution as its sole method, finally adopted lethal injection in 2009, doing so after its Supreme Court declared the electric chair unconstitutional, solidifying lethal injection’s dominance.

Lethal injection thus emerged as the most common form of legal execution in the United States, effectively supplanting the older, often controversial methods such as electrocution, gas inhalation, hanging, and firing squad. It marked a significant evolution in the practice of capital punishment, driven by a perception of enhanced humanity.

4. **Chapman’s Protocol: The Blueprint for a ‘More Humane’ Death**The day after Oklahoma’s lethal injection law was enacted, on May 11, 1977, the state’s medical examiner, Jay Chapman, proposed a specific, systematic method intended to be less painful. This proposal, known as Chapman’s protocol, would become the foundational blueprint for lethal injections in the United States.

Chapman’s protocol outlined a precise procedure: “An intravenous saline drip shall be started in the prisoner’s arm, into which shall be introduced a lethal injection consisting of an ultrashort-acting barbiturate in combination with a chemical paralytic.” This formulation was designed to ensure a rapid loss of consciousness, followed by the cessation of vital bodily functions.

Crucially, this protocol received validation from an authority in the medical field: anesthesiologist Stanley Deutsch, formerly the Head of the Department of Anaesthesiology of the Oklahoma University Medical School, approved the method. This endorsement lent significant credibility to the protocol, reassuring proponents of its supposed efficacy and humaneness.

Texas, in a pivotal move on August 29, 1977, adopted this new method of execution, formally switching from electrocution. This transition culminated in the execution of Charles Brooks, Jr., on December 7, 1982, in Texas, marking him as the first individual in any U.S. state or territory worldwide to be put to death by lethal injection, forever etching this date into the history of capital punishment.

5. **Global Embrace, Global Questions: International Usage and Abolition**The United States pioneered the widespread use of lethal injection, but its adoption soon transcended national borders. The People’s Republic of China began utilizing it in 1997, followed by Guatemala in 1996, the Philippines in 1999, Thailand in 2003, Taiwan in 2005, and Vietnam in 2013, solidifying its status as a globally recognized, albeit controversial, method of execution.

However, the path of lethal injection has not been universally consistent across these nations. While Guatemala’s law still permits the death penalty and lethal injection as the sole method, no executions have been carried out since 2000, and the country later abolished the death penalty for civilian cases in 2017. Similarly, the Maldives has never performed an execution since its independence, despite adopting the method. Taiwan and Nigeria also permit lethal injection but have not conducted any executions using this manner.

The Philippines, for instance, employed lethal injection for all seven executions carried out between 1999 and 2000. Yet, the country eventually re-abolished the death penalty in 2006, signaling a retreat from the practice despite its initial embrace of the method.

In some cases, the implementation drew significant public attention. Guatemalan law, despite the lack of recent executions, allowed for the live televised double executions of Amílcar Cetino Pérez and Tomás Cerrate Hernández in 2000. This event, witnessed publicly, highlighted the profound impact and ongoing debate surrounding methods of execution, even those deemed more ‘humane.’

6. **The Standard Arsenal: Understanding the Three-Drug Protocol**In the United States, the typical lethal injection procedure is a carefully orchestrated sequence designed to ensure the condemned person’s demise. It usually begins with the individual being securely fastened onto a gurney, followed by the insertion of two intravenous cannulas, or “IVs,” one in each arm. While only one is strictly necessary, the second serves as a crucial backup, an acknowledgment of potential procedural failures.

Lines extending from the IVs lead into an adjacent room, connecting to the prisoner’s bloodstream. These lines are meticulously secured to prevent dislodgment during the injections. Intriguingly, the arm is routinely swabbed with alcohol, and the equipment used is sterilized. Explanations for these sterile precautions, despite the procedure’s terminal intent, include adherence to routine medical procedures, the possibility of a stay of execution, and the protection of prison personnel from accidental needle stick injuries.

Once the lines are connected, saline drips are initiated in both arms. This preparatory step is standard medical procedure, ensuring that the IV lines are unobstructed and that the subsequent lethal chemicals will not precipitate or block the needles, guaranteeing their delivery to the subject. A heart monitor is also attached to the inmate, allowing for the precise observation of cardiac activity throughout the process.

Most states follow a three-drug protocol, a sequential administration engineered to first induce unconsciousness, then paralyze respiratory muscles, and finally, cause cardiac arrest. Crucially, the drugs are never mixed externally to prevent precipitation, and their sequential injection is vital to achieving the desired physiological effects in the correct order. Administering a highly concentrated potassium chloride solution while the person is still conscious could inflict “severe pain at the site of the IV line, as well as along the punctured vein,” leading to an agonizing cardiac arrest.

7. **Sodium Thiopental/Pentobarbital: The Induction of Unconsciousness**The first critical component in the conventional lethal injection protocol is an ultra-short-acting barbiturate, typically sodium thiopental, or more recently, pentobarbital. This anesthetic agent is deployed in a significantly high dose, serving the primary purpose of rapidly rendering the condemned person unconscious, ideally within mere seconds.

For lethal injection, a dose of 2 to 5 grams of sodium thiopental is commonly administered, a quantity vastly exceeding the typical anesthesia induction dose of 0.35 grams. At this “mega-dose,” loss of consciousness can be induced in as little as 10 seconds, and certainly within 30-45 seconds at the standard clinical dose. Beyond inducing unconsciousness, this drug also acts to depress respiratory activity, contributing to the ultimate cause of death.

Pharmacologically, a full medical dose of thiopental reaches the brain in about 30 seconds. While only approximately 15% of the drug remains in the brain five to twenty minutes post-injection, with the rest distributing to other body parts, a mega-dose as used in lethal injection behaves differently. Repeated or very high single doses accumulate in high concentrations in body fat, from which thiopental is gradually released over time. This characteristic explains how an ultra-short-acting barbiturate can be utilized for the long-term induction of medical coma, with its half-life extending to about 11.5 hours.

Historically, thiopental has been a well-studied drug for inducing coma, with protocols ranging from 500 mg to 1.5 grams. The dose used for capital punishment, typically 5 grams in most states to ensure effectiveness, is roughly “3 times more than the dose used in euthanasia protocols,” which range from 1 to 2 grams. Due to a shortage of sodium thiopental beginning in late 2010—a result of activist pressure and manufacturers halting supply to U.S. prisons—pentobarbital, often used for animal euthanasia, has since become the primary sedative in lethal injections within the United States.”

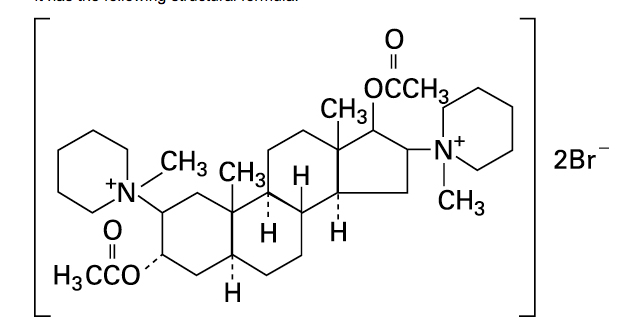

8. **Pancuronium Bromide: The Enforcer of Silence**With the condemned person hopefully rendered unconscious by the initial anesthetic, the lethal injection protocol moves to its second, equally critical phase: the administration of pancuronium bromide. This drug, a non-depolarizing muscle relaxant, is a powerful paralytic agent designed to profoundly affect the body’s musculature, including the diaphragm and other vital respiratory muscles. Its typical dosage in capital punishment, 0.2 mg/kg, ensures a comprehensive and sustained paralysis.

The primary function of pancuronium bromide is to cease all voluntary and involuntary muscle movements, leading inevitably to death by asphyxiation. The drug works by blocking the action of acetylcholine at the motor end-plate of the neuromuscular junction, preventing muscle fibers from contracting. While its paralytic effects can last between four to eight hours, the paralysis of respiratory muscles is sufficient to cause death in a considerably shorter timeframe, typically leading to the cessation of breathing.

However, the use of pancuronium bromide introduces a profound ethical and practical dilemma. If the initial anesthetic, sodium thiopental or pentobarbital, fails to induce complete and sustained unconsciousness—a concern frequently raised by opponents—the condemned individual would remain fully aware but utterly unable to move or express the excruciating pain of the subsequent drugs. This enforced silence, a horrifying potential outcome, fundamentally challenges the “humane” premise of the entire procedure, rendering any suffering invisible to witnesses.

9. **Potassium Chloride: The Final, Fatal Surge**Following the paralytic, the final and perhaps most immediate agent in the standard three-drug protocol is potassium chloride. This potassium salt is administered to induce a fatal cardiac arrest, bringing about the condemned person’s death by dramatically altering the heart’s electrical activity. Typically, a dose of 100 mEq (milliequivalents) is delivered as a bolus injection, rapidly elevating extracellular potassium levels in the bloodstream.

Under normal physiological conditions, potassium is an essential electrolyte with strict regulatory mechanisms governing its balance, particularly crucial for cells generating action potentials, such as those in the heart. A rapid, concentrated infusion of potassium, far exceeding therapeutic levels, creates a state of acute hyperkalemia. This causes a depolarization of the resting membrane potential of heart muscle cells, especially impacting the pacemaker cells, which are responsible for initiating the heartbeat.

The effect of this potassium surge on the heart’s electrical conduction is profound and biphasic. Initial concentrations might shorten the action potential duration, increasing conduction velocity. However, as potassium concentrations soar beyond 14 mEq/L, a critical threshold is reached where enough sodium channels in the heart muscle cells become inactivated, preventing the generation of new action potentials. This effectively stops the heart from beating, leading to asystole and cardiac arrest, a process that can occur within 30 to 60 seconds if administered correctly.

Crucially, if the condemned individual were not fully unconscious, the bolus injection of a highly concentrated potassium chloride solution would inflict “severe pain at the site of the IV line, as well as along the punctured vein,” as the electrical activity of the heart muscle is disrupted. The transition from a conscious state to an agonizing cardiac arrest without the ability to cry out due to the paralytic agent describes a scenario frequently invoked by those who deem lethal injection cruel and unusual punishment.

10. **A String of Complications and Evolving Alternatives**Despite its intended efficiency, lethal injection has been plagued by a litany of complications, driving states to reconsider and adapt their protocols. By early 2014, a rising shortage of suitable drugs—a direct consequence of the European Union’s 2011 ban on the export of lethal injection drugs and pharmaceutical manufacturers, including Pfizer, halting sales to U.S. prisons—forced a re-evaluation of execution methods across the nation.

This scarcity led some states to explore older, previously abandoned methods. Tennessee, for example, passed a law in May 2014 allowing the use of the electric chair if lethal injection drugs were unavailable. Similarly, Wyoming and Utah contemplated bringing back the firing squad, signaling a potential regression in the pursuit of “humane” execution. The crisis also prompted the development of novel drug cocktails, such as Nebraska’s 2018 use of diazepam, fentanyl, cisatracurium, and potassium chloride, and Florida’s 2017 protocol with etomidate, rocuronium bromide, and potassium acetate.

Adding to the procedural concerns, instances of botched executions have drawn significant scrutiny, revealing the stark reality behind the sterile facade. In January 2015, Oklahoma mistakenly used potassium acetate instead of potassium chloride for Charles Frederick Warner’s execution, a critical error that underscores the inherent risks. There have also been harrowing accounts of inmates gasping for air for extended periods, some for “approximately 10 to 13 minutes,” due to complications. Such incidents, coupled with delays in finding suitable veins that can prolong the entire procedure for up to two hours, as seen with Christopher Newton’s execution, highlight the profound and often agonizing failures of a system designed for a swift, painless demise.

Read more about: Beyond the Garage: 12 Critical Signs Your Old Car is Telling You It’s Time for a New One

11. **The Emergence of Single-Drug Protocols and Midazolam**In response to both drug shortages and controversies surrounding the three-drug cocktail, several U.S. states began transitioning to single-drug lethal injection protocols. Ohio pioneered this shift on December 8, 2009, using a single, massive dose of sodium thiopental. This approach aimed to ensure a rapid and painless onset of anesthesia without the complications or ethical quandaries posed by the paralytic and cardiac arrest agents if the initial sedative failed.

Ohio’s new protocol, developed after the incomplete execution of Romell Broom, also incorporated secondary fail-safe measures, including intramuscular injections of midazolam, followed by sufentanil or hydromorphone, in case intravenous administration proved problematic. This adaptability marked a significant evolution in execution procedures, with states like Washington following suit, proclaiming death within minutes after the single-drug injection of sodium thiopental. Eight states (Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, Missouri, Ohio, South Dakota, Texas, and Tennessee) have since adopted or used this single-drug protocol.

However, the continued scarcity of sodium thiopental, due to manufacturers like Hospira ceasing production for execution use, led to further innovation. Pentobarbital, initially used in three-drug cocktails, subsequently became the primary sedative for single-drug executions. Furthermore, some states like Florida (October 2013) and Ohio (November 2013) adopted new three-drug protocols where midazolam replaced thiopental or pentobarbital as the initial sedative. This shift, while addressing drug availability, sparked new legal challenges concerning midazolam’s efficacy in reliably rendering a person unconscious, reigniting debates about the “cruel and unusual” nature of lethal injection.

12. **The Medical Profession’s Ethical Standpoint**The involvement of medical professionals in executions has long been a contentious issue, pitting professional ethics against state mandates. The American Medical Association (AMA), guided by its core principle of preserving life, unequivocally states that a physician “should not be a participant” in executions in any professional capacity. This prohibition stems from fundamental medical ethics, such as the Geneva Promise, which obligates physicians to dedicate their lives to the service of humanity and not use their medical knowledge to violate human rights.

The AMA’s stance, however, does allow for limited participation, specifically “certifying death, provided that the condemned has been declared dead by another person” and “relieving the acute suffering of a condemned person while awaiting execution.” Nevertheless, the organization lacks the authority to enforce a nationwide ban, as medical licensing is handled at the state level. This jurisdictional gap has led to situations where states navigate around these ethical guidelines.

For instance, some state laws, such as Delaware’s, explicitly stipulate that “the administration of the required lethal substance or substances required by this section shall not be construed to be the practice of medicine.” This legal maneuver effectively removes the procedure from the direct purview of medical ethics and professional oversight. Consequently, prison employees, often trained in venipuncture but lacking advanced medical expertise in anesthesia, are frequently tasked with inserting IVs and administering the drugs, leading to concerns about the competence and potential for errors during these solemn procedures. The brief for the U.S. courts written by accessories for the State of Ohio even implied an inability to find physicians willing to participate in protocol development, underscoring the deep ethical resistance within the medical community.

13. **Legal Battles: Challenging the Eighth Amendment**The constitutionality of lethal injection, particularly under the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against “cruel and unusual punishment,” has been a persistent battleground in U.S. courts. A pivotal moment arrived in 2006 with the Supreme Court’s ruling in *Hill v. McDonough*, which affirmed that death-row inmates could challenge state lethal injection procedures through federal civil rights lawsuits. This opened the floodgates for numerous challenges in lower courts, leading to conflicting judgments.

Some courts, assessing procedures in states like California, Florida, and Tennessee, found lethal injection as practiced to be unconstitutional, leading to moratoriums and costly overhauls, such as California’s unused $800,000 lethal injection facility. Conversely, courts in Missouri, Arizona, and Oklahoma deemed their methods constitutionally acceptable. This judicial divergence highlighted the lack of a uniform legal standard, prompting the Supreme Court to intervene again.

In 2007, the Supreme Court agreed to hear *Baze v. Rees*, a case from Kentucky, to address whether its standard three-drug protocol comported with the Eighth Amendment and to establish a consistent legal standard for these challenges. In April 2008, the Court upheld Kentucky’s method in a 7–2 decision, bringing a temporary end to the nationwide de facto moratorium on executions. Later, in *Glossip v. Gross* (2015), the Court again upheld a modified protocol, specifically Oklahoma’s use of midazolam in place of unavailable drugs, asserting that inmates failed to demonstrate a high risk of severe pain or a practical, less risky alternative. These landmark rulings, while providing some clarity, have not extinguished the ongoing legal scrutiny, as evidenced by *Russell Bucklew’s* 2019 appeal based on a rare medical condition potentially interfering with the drugs’ effects, though the Court ultimately ruled against him.

14. **The Enduring Controversy: Appearance Versus Reality**At the heart of the opposition to lethal injection lies a profound skepticism regarding its purported painless and humane nature. Critics argue that the procedure is meticulously designed to create an *appearance* of serenity, rather than actually providing a dignified death. The ultrashort-acting barbiturate, sodium thiopental, is typically used as an induction agent, not for sustained anesthesia in surgery, leading opponents to fear “anesthesia awareness”—that the drug may wear off, leaving inmates conscious but paralyzed.

This paralysis, induced by pancuronium bromide, becomes a cruel enforcer of silence. If conscious, the condemned would be unable to express the “agonizing death through suffocation” from the paralytic effects or the “intense burning sensation” caused by potassium chloride. Concerns are also raised about the appropriate dosage, as thiopental rapidly redistributes out of the brain, potentially leaving insufficient amounts to maintain unconsciousness, especially when rigid protocols prevent individualized dosing.

A significant flaw highlighted by opponents is the method of administration itself. With prison personnel, rather than trained anesthesiologists, often administering the drugs, the risk of failure to induce or maintain unconsciousness is greatly increased. As Jay Chapman, the originator of the American method, candidly remarked, “It never occurred to me when we set this up that we’d have complete idiots administering the drugs.” Furthermore, remote administration, where syringes are injected from an adjacent room, raises concerns that insufficient amounts of the lethal drugs might reach the inmate’s bloodstream, exacerbating the risks of a torturous execution. These arguments converge on the chilling conclusion that lethal injection, despite its modern facade, can indeed constitute cruel and unusual punishment, perpetuating the very suffering it was designed to prevent.

In summation, the journey of lethal injection from a proposed humane alternative to the dominant form of capital punishment has been fraught with complexity, controversy, and profound ethical challenges. While states continue to refine protocols, contend with drug shortages, and navigate legal precedents, the core debate endures. It is a debate that transcends pharmacology and procedure, touching upon fundamental questions of justice, human dignity, and the very definition of a “humane” death when the ultimate weapon of the state is deployed. The quest for an execution method that satisfies both societal demands for retribution and an evolving understanding of humaneness remains an intricate, unfinished chapter in the history of capital punishment.