The world of acting, a tapestry woven with countless lives, triumphs, and profound transformations, is far more complex than the glittering red carpets or the sudden spotlight of a breakout role. It’s a journey fraught with historical prohibitions, societal shifts, and the relentless pursuit of authenticity. Before the digital age democratized content creation, before Hollywood became a global juggernaut, the very definition and acceptance of an “actor” evolved through millennia, shaping not just entertainment, but cultural identity itself.

From being a revered orator in ancient Greece to a scorned wanderer in the Middle Ages, and then finally ascending to the status of a knighted celebrity, the actor’s path has been anything but linear. This dramatic evolution highlights a fundamental truth: the stage, whether literal or metaphorical, has always reflected society’s values, prejudices, and aspirations. We often marvel at the performances, but rarely delve into the profound historical currents that allowed them to exist, or, indeed, prevented them.

This article embarks on an insightful journey, pulling back the curtain on the “unseen stages” that have defined the acting profession. We’ll explore how the very act of portraying a character has challenged norms, shattered taboos, and ultimately paved the way for the diverse, celebrated, and often scrutinized world of acting we know today. From Thespis’s groundbreaking monologue to the influential actor-managers of the 19th century, prepare to discover the true saga of the performer.

1. **The Origin Story: Thespis and the Birth of Acting**Our story begins in 534 BC, a year that marks a seismic shift in the history of storytelling. Before this momentous occasion, Grecian narratives were delivered through a blend of song, dance, and third-person narration, a communal experience rather than an individual embodiment. It was at the Theatre Dionysus that a Greek performer named Thespis stepped onto the stage, forever changing the trajectory of performance art.

His innovation was simple yet revolutionary: Thespis became the first known person to speak words *as a character* in a play or story. This wasn’t merely recitation; it was interpretation, an act of becoming. He transitioned from merely telling a story to actively portraying a distinct persona, creating a fundamental divergence that would define acting for centuries to come. The analogous Greek term, *hupokritḗs*, literally meaning “one who answers,” perfectly encapsulates this new dimension of dialogue and interaction that Thespis introduced.

In recognition of this pioneering spirit, actors around the world are still colloquially known as “Thespians.” It’s a term that carries the weight of history, linking every performer, from a Broadway star to a local theatre enthusiast, back to that singular moment of innovation. It underscores the profound impact one individual had on an art form that now permeates every aspect of global culture.

However, it’s crucial to remember that the theatre of ancient Greece, a crucible of tragedy, comedy, and satyr plays, was an exclusively male domain. While Thespis opened the door to character portrayal, that door was only accessible to men, setting a precedent for gender-based exclusions that would unfortunately echo through various eras and cultures for a considerable time.

2. **Gendered Stages: Ancient Bans and Roman Exceptions**Venturing further into antiquity, the landscape of the stage reveals stark gender disparities. In ancient Greece, the foundational cradle of Western theatre, women were unequivocally barred from appearing on stage. This wasn’t a subtle preference; it was a deeply ingrained cultural practice where male actors performed all roles, including those of female characters, a convention that speaks volumes about the societal roles and restrictions placed upon women in that era.

The reasons behind this absolute prohibition remain a subject of historical contemplation. Beyond the practicalities of a male-dominated public sphere, there have even been academic speculations as to whether women were permitted to merely *watch* plays as audience members. This suggests a profound level of societal control over women’s public presence and participation, extending even to passive engagement with artistic expression.

In stark contrast to the rigid Greek system, the theatre of ancient Rome offered a glimpse of a different reality, where female performers were, in fact, allowed. While the majority of these women were often employed in non-speaking roles, primarily for dancing or mime, a significant minority did achieve speaking parts. This demonstrates a greater, albeit still limited, acceptance of women in certain theatrical capacities.

Moreover, some Roman actresses, such as Eucharis, Dionysia, Galeria Copiola, and Fabia Arete, rose to prominence, achieving wealth, fame, and critical recognition for their artistry. These trailblazing women even formed their own acting guild, the Sociae Mimae, which was evidently quite wealthy. This remarkable achievement highlights that even in ancient times, amidst pervasive patriarchal structures, there were instances where female talent and collective organization could carve out a space for professional artistic endeavors.

3. **Medieval Meanderings: The Church’s Scorn and Amateur Troupes**As the Western Roman Empire receded into history, Western Europe plunged into a period of general disorder, often referred to as the Early Middle Ages. During this era, the social standing of actors plummeted dramatically. Traveling acting troupes, nomadic bands performing crude scenes wherever an audience could be found, were typically viewed with profound distrust and suspicion across Europe.

This negative perception was exacerbated by the powerful influence of the Church during the Dark Ages. Actors were vehemently denounced, frequently labeled as dangerous, immoral, and pagan. Such was the severity of this condemnation that in many parts of Europe, adhering to traditional beliefs of the region and time, actors were explicitly denied Christian burial. This extreme social and religious ostracization highlights the precarious existence of performers during this tumultuous period.

Ironically, even as professional actors faced such harsh judgment, the Church itself began to play a pivotal, albeit unintentional, role in the eventual re-development of theatre. By the Early Middle Ages, churches across Europe started staging dramatized versions of biblical events—liturgical dramas. These performances, which spread from Russia to Scandinavia to Italy by the mid-11th century, marked a significant step in re-integrating dramatic storytelling into communal life, albeit in a religious context.

By the Late Middle Ages, theatre had truly begun to flourish again, with plays being produced in 127 towns. These vernacular Mystery plays often incorporated comedic elements, featuring actors portraying devils, villains, and clowns. The majority of these performers were drawn from the local population, primarily amateurs temporarily engaged for specific festivities. While English amateur performers remained exclusively male, it is notable that other countries during this period *did* feature female performers in these community-based productions, hinting at regional variations in acceptance.

4. **Renaissance Rebirth: Commedia dell’arte and Aristocratic Players**The slow and arduous journey back to professional acting after antiquity truly gained momentum during the Renaissance, particularly in Italy. This period saw the re-emergence of professional companies, with the names of members from a Padova troupe in 1545 being the first known since ancient times. Initially, these recorded companies were all-male, suggesting that the professional stage for women was still a dream rather than a reality.

However, it was the vibrant, improvisational phenomenon of Commedia dell’arte troupes that profoundly shaped this theatrical rebirth. Beginning in the mid-16th century, these actor-centered ensembles captivated audiences across Europe for centuries. Their performances relied on loose frameworks of situations and stock characters, allowing actors remarkable freedom to improvise, demanding a high level of skill and quick wit. Crucially, Commedia dell’arte paved the way for professional women to perform early on, a groundbreaking development that set it apart from previous eras.

It is within this context that we encounter the first documented professional Italian actresses. Lucrezia Di Siena, whose name graces an acting contract from Rome on October 10, 1564, is often cited as the first Italian actress known by name since ancient Rome. Following her, Vincenza Armani and Barbara Flaminia emerged as the first *primadonnas* and the first well-documented actresses not just in Italy, but across Europe. Their rise signaled a monumental shift in the theatrical landscape.

From the 1560s onward, actresses became the norm in Italian theaters. As these Italian companies toured abroad, their female performers became the very first women actors to grace the stages in many countries, exporting a revolutionary concept of gender inclusion in professional theatre. This cultural exchange introduced audiences to the power and artistry of female performers, chipping away at long-held prejudices.

Beyond Italy, women also began appearing on stage in other parts of Europe during the 16th century. In Spain, the Golden Age theatre (1590–1641) saw women performing from its very beginning, with figures like Ana Muñoz and Jerónima de Burgos making their mark. France too witnessed the activity of professional actresses in the second half of the 16th century, though their documentation remains somewhat scarce compared to their Italian counterparts. Marie Vernier, also known as Mlle La Porte, stood out as a leading lady and co-director of Valleran-Lecomte’s acclaimed theatre company, showcasing early examples of female leadership on stage.

5. **The Restoration Revolution: Women’s Debut on the English Stage**While Italy, Spain, and France embraced female performers during the Renaissance, England remained a notable holdout. For the first half of the 17th century, the English stage continued its age-old tradition of male actors, often boys, playing all female roles. This stark contrast highlights the unique cultural and religious forces at play within England, delaying a change that was already unfolding across much of Western Europe.

The English audience did, however, get fleeting glimpses of female actors through visiting foreign theatre companies. The Italian actress Angelica Martinelli, performing as early as 1578, is believed to be one of the first foreign actresses to appear in England. Yet, these rare appearances did not spark immediate reform. A particularly telling incident occurred in November 1629, when a French theatre company featuring actresses made a guest appearance at London’s Blackfriars Theatre, only to be met with a hostile reception, as the actresses were “hissed, booed and pippin-pelted from the stage.” This visceral reaction underscores the deep-seated resistance to women on the English stage.

The real catalyst for change came after an eighteen-year Puritan prohibition on drama, which viewed theatre as immoral, was finally lifted with the English Restoration of 1660. This societal shift, driven in part by King Charles II’s personal enjoyment of watching actresses, marked a pivotal moment. Charles II issued royal letters patent to Thomas Killigrew and William Davenant, granting them a monopoly over two London theatre companies.

Crucially, these patents were reissued in 1662 with revisions that explicitly allowed actresses to perform for the first time. This formal legalization fundamentally altered the landscape of English theatre. Margaret Hughes is widely credited as the first professional actress to grace the English stage, her debut symbolizing the end of an era and the dawn of a new one where women could finally claim their rightful place in the spotlight.

Read more about: Behind the Curtain: An In-Depth Look at the Actor’s Craft, History, and Industry Realities

6. **The Rise of the Star: 19th Century Actor-Managers and Celebrity Culture**The 19th century ushered in a dramatic reversal of fortunes for actors, transforming their societal standing from a previously negative reputation to an honored and popular profession. This profound shift was largely fueled by the burgeoning phenomenon of celebrity, as audiences began to flock specifically to see their favorite “stars” perform, elevating individual performers to iconic status. The era of the anonymous strolling player was definitively over.

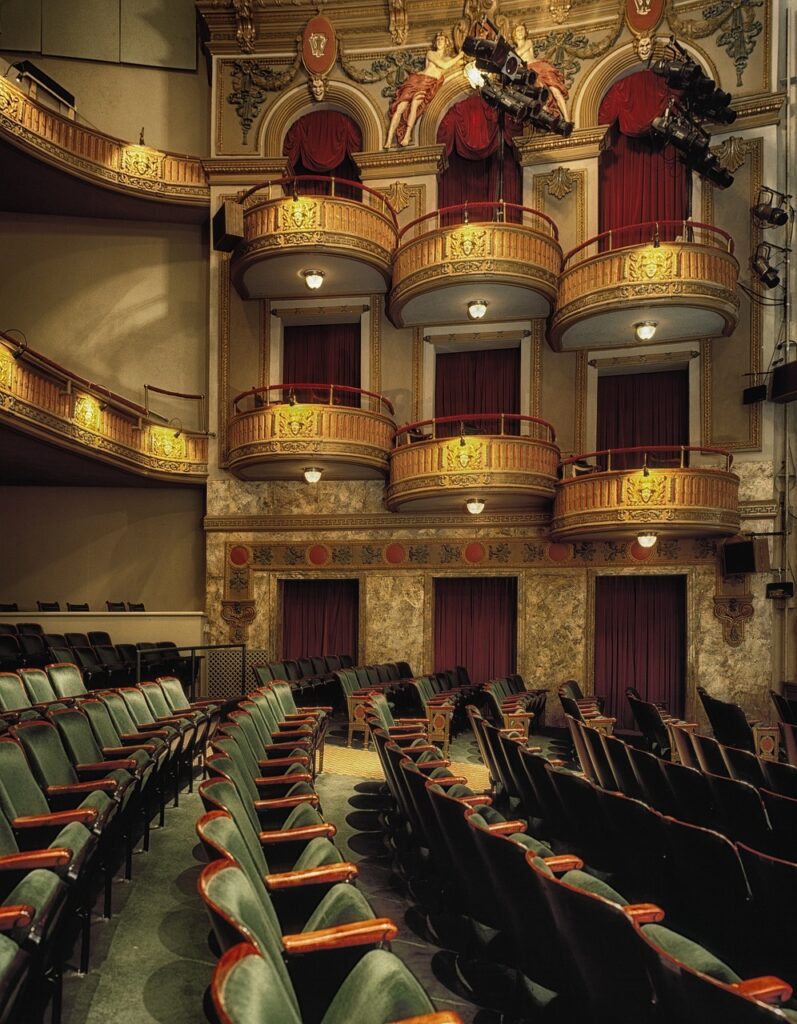

Central to this transformation was the emergence of the actor-manager. These remarkable individuals were not merely performers; they were entrepreneurs, artists, and impresarios rolled into one. They formed their own companies, exerting complete control over their ensembles, the productions they staged, and crucially, the financial aspects of their theatrical ventures. When successful, these actor-managers cultivated loyal, permanent clienteles who eagerly anticipated their next offering.

To further expand their reach and influence, these companies embarked on extensive national tours, bringing a repertoire of well-known plays, particularly those by Shakespeare, to audiences far and wide. This popularization of theatre, combined with fervent public discourse in newspapers, private clubs, pubs, and coffee shops, where the merits of stars and productions were hotly debated, cemented the actor’s place at the heart of popular culture.

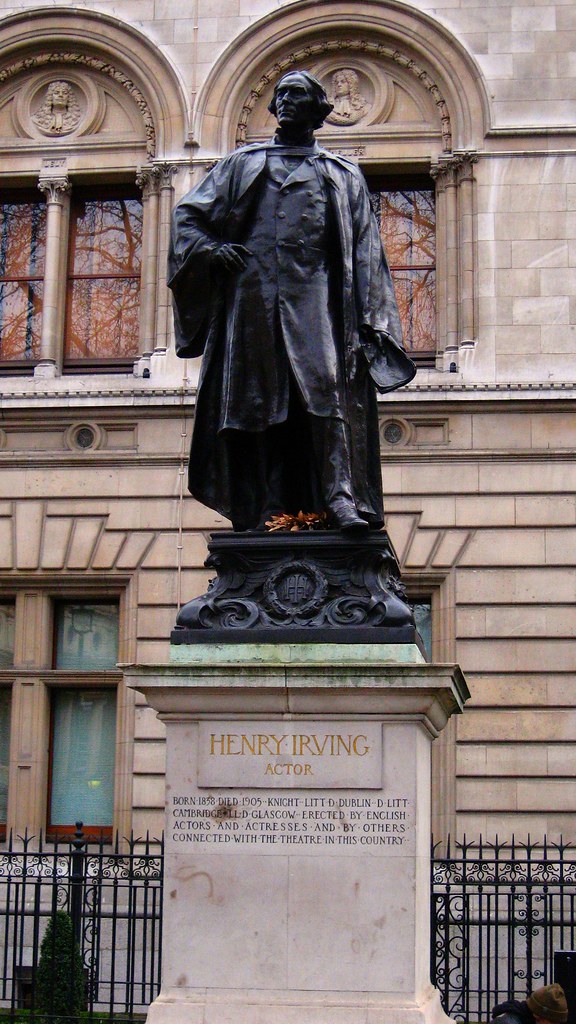

Henry Irving (1838–1905) stands as the quintessential example of the British actor-manager’s power and prestige. Renowned for his captivating Shakespearean roles, Irving introduced numerous innovations, such as dimming the house lights to direct audience attention more intently to the stage. His company’s extensive tours across Britain, Europe, and the United States demonstrated the immense power of star actors and celebrated roles to draw enthusiastic crowds, proving the commercial and artistic viability of the star system. His knighthood in 1895 was not just a personal honor; it was a profound symbol of the full acceptance of the acting profession into the higher echelons of British society, a far cry from the medieval denunciations.

The arc of acting history doesn’t end with the triumphs of the 19th-century actor-managers; rather, it enters a new, complex phase as the 20th century dawns, grappling with evolving economics, new technologies, and a deeper interrogation of the craft itself. While the past laid the groundwork, the modern era has refined, challenged, and sometimes even blurred the lines of what it means to be a performer. From the specialized roles behind the scenes to the intricate psychology of character portrayal, and from global variations in women’s entry onto the stage to the ongoing debates about terminology and pay, the story of the actor continues to unfold with fascinating depth.

7. **The Twentieth Century Shift: Specialization and Corporate Power**As the theatrical lights brightened into the 20th century, the grand, all-encompassing figure of the actor-manager, once the titan of the stage, gradually began to recede. This wasn’t a sudden dramatic exit, but rather a slow, strategic retreat, driven largely by the changing economics and growing complexity of large-scale productions. The demands of combining artistic genius with shrewd business acumen became increasingly difficult to balance, ushering in an era of necessary specialization.

This shift saw the emergence of new, distinct roles within the theatrical ecosystem: stage managers, meticulously orchestrating every technical and logistical detail, and theatre directors, solely focused on the artistic vision and interpretation of the play. It was a logical evolution, allowing individual experts to hone their craft without the overwhelming burden of managing an entire company’s finances and operations. No longer was one person expected to be both the leading star and the chief financier; the roles fragmented for efficiency.

Financially, the landscape transformed dramatically. Operating out of major cities now required significantly larger capital investments, far beyond what even a highly successful individual actor-manager could typically command. The solution materialized in the form of corporate ownership, leading to the rise of powerful chains of theatres like the Theatrical Syndicate, Edward Laurillard, and most notably, The Shubert Organization. These entities consolidated power, streamlined operations, and fundamentally reshaped the business of entertainment.

With corporate backing, theaters in bustling metropolises began catering heavily to tourists, favoring long, lucrative runs of highly popular plays, with musicals often leading the charge. In this environment, big-name stars, the very celebrities whose allure had begun to blossom in the previous century, became not just desirable but absolutely essential. Their drawing power guaranteed audiences, further solidifying the star system and marking a departure from the company-centric model of earlier eras.

8. **Mastering the Craft: Core Acting Techniques**Beyond the shifting business models, the 20th century also witnessed a profound intellectualization of the actor’s craft, as artists and theorists delved deep into the psychological and emotional mechanics of performance. This era gave birth to foundational acting techniques that continue to shape how performers approach their roles, moving far beyond mere recitation to a quest for profound authenticity.

Among these, Classical acting emerged as a comprehensive philosophy, integrating the full spectrum of an actor’s tools: body, voice, imagination, personalization, improvisation, external stimuli, and rigorous script analysis. It sought to create a holistic approach, drawing from various influences to achieve a refined and expressive performance that resonated with both intellectual and emotional depth, recognizing the multifaceted nature of the actor’s art.

Central to modern acting pedagogy is Konstantin Stanislavski’s system, a revolutionary approach where actors are encouraged to draw upon their own feelings and personal experiences to embody the “truth” of their characters. This method isn’t about simply mimicking emotions; it’s about genuine internalization, placing oneself squarely in the character’s mindset and finding common ground to deliver a portrayal that feels undeniably real and deeply human to the audience.

Building on Stanislavski’s insights, Lee Strasberg formulated Method acting, a range of techniques designed to achieve better characterizations by encouraging actors to use their own experiences to personally identify with their roles. While a complex and sometimes controversial approach, its impact is undeniable, as seen in the work of actors like Marlon Brando, who, despite his personal aversion to Strasberg’s teachings, became a powerful example of its profound effects. Other influential techniques like Stella Adler’s and Sanford Meisner’s also stemmed from Stanislavski’s pioneering work, each offering a distinct path to authentic performance. Meisner, for instance, championed total focus on the other actor, creating an immediate, responsive, and incredibly authentic connection within a scene.

Read more about: Beyond the Screen: 15 Stunt Realities Where Performers’ Fear Was Absolute, and AI’s Looming Impact

9. **Beyond Gender Norms: The Art of Cross-Gender Acting**While the historical journey saw significant battles fought for women to simply *exist* on stage, the evolution of acting has also brought forth the fascinating and often provocative tradition of cross-gender casting. This practice, far from being a modern invention, boasts a rich heritage rooted in theatre’s earliest days, particularly as a tool for comic effect. Shakespeare himself frequently employed overt cross-dressing, a device that delighted audiences and often drove the plots of his comedies.

In the realm of modern cinema, this comedic tradition has flourished, leading to iconic performances suchporters, such as Jack Gilford in *A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum* or Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon famously masquerading as women in *Some Like It Hot*. These portrayals highlight the enduring power of gender reversal to generate laughter, often by subverting expectations and playing on societal stereotypes, creating memorable and beloved cinematic moments.

However, the landscape of cross-gender acting has also grown far more nuanced and complex, moving beyond mere laughs. We’ve seen intricate narratives where a woman plays a woman pretending to be a man, who then, in a layer of exquisite irony, pretends to be a woman, as exemplified by Julie Andrews in *Victor/Victoria* or Gwyneth Paltrow in *Shakespeare in Love*. These roles delve into deeper explorations of identity and perception, challenging audiences to consider the layers of performance inherent in everyday life.

Furthermore, a significant, albeit less common, subset of cross-gender casting involves women taking on male roles, earning critical acclaim and even awards. Linda Hunt’s Academy Award-winning portrayal of Billy Kwan in *The Year of Living Dangerously* and Cate Blanchett’s Oscar-nominated turn as Jude Quinn, a fictionalized Bob Dylan, in *I’m Not There* are powerful testaments to the artistic merit and transformative potential of such casting. These performances transcend gender, proving that exceptional acting can illuminate universal truths regardless of the character’s assigned .

In contemporary media, especially with the rising visibility of non-binary and transgender characters, cross-gender acting continues to evolve. While cisgender actors have taken on trans roles, such as Hilary Swank as Brandon Teena in *Boys Don’t Cry*, there’s a growing recognition and demand for authentic representation. Simultaneously, modern productions, particularly in live theatre, embrace gender fluidity, with roles like Edna Turnblad in *Hairspray* traditionally played by men, and women frequently stepping into male roles in classical plays where gender isn’t central to the character’s essence, further pushing the boundaries of traditional casting.

Read more about: The Enduring Craft of Acting: A Comprehensive Look at Its History, Techniques, and Societal Evolution

10. **Global Stages, Diverse Journeys: Women in European Theatre (Post-Restoration)**While England’s Restoration marked a significant moment for women on stage, the journey across the rest of Europe was far from uniform, each nation carving its own path, often grappling with distinct social norms and theatrical traditions. The mid-17th century saw women making their debut in native travelling theatre companies in Germany and the Netherlands, typically as wives and daughters performing under male supervision within family troupes. This model, while restrictive, provided a foothold.

Soon after, these pioneering women broke into the more prestigious permanent city theatres. Ariana Nozeman, for instance, made her groundbreaking debut on April 19, 1655, in Amsterdam, becoming the first woman to play a leading role in a Dutch public play. In Germany, “female players” were noted in Frankfurt in September 1655, with figures like Catharina Elisabeth Velten not only acting with her family but later managing her husband’s theatre, actively continuing the policy of employing women. These were crucial steps, often driven by individual determination and a gradual societal acceptance.

Further East and North, the story unfolded differently. Countries like Sweden, Russia, and Poland lacked established national theatres with native professional actors until much later. Here, foreign actresses often graced the stage decades before any local female — or even male — performers emerged. In Sweden, Dutch actresses performed as early as 1653, but it wasn’t until 1737, with the inauguration of the Kungliga svenska skådeplatsen, that native Swedish actresses like Beata Sabina Straas began their careers.

Similarly, Russia’s first Tsar-founded theatre in 1672 employed foreign women actors, but it took until the 1756 Decree of the Imperial Theatres for native Russian women, including Avdotya Mikhailova and Elizaveta Zorina, to receive formal training and perform. Poland-Lithuania’s National Theatre, founded in 1765, similarly integrated women like Antonina Prusinowska and Wiktoria Leszczyńska into its pioneering cohort from the outset. These journeys highlight that while the absence of an explicit ‘ban’ might have been less dramatic than in England, the establishment of national theatrical infrastructure was the true catalyst for women’s professional opportunities.

Even later, in 19th-century Greece, following its independence in 1830, a burgeoning interest in theatre initially relied on amateur actors or foreign (Italian) actresses for female roles. It wasn’t until November 1840 that Maria Angeliki Tzivitza became the first Greek actress, albeit retiring after just two performances. The Athenian Theatre Committee, founded in 1842, explicitly aimed to educate professional Greek actors, but faced immense difficulty finding women due to societal disapproval. Ekaterina Panayotou, signing her contract on November 8, 1842, holds the distinction of being Greece’s first professional actress with formal training, a testament to the persistent struggle for respectability and opportunity.

11. **Cultural Curtains: Women in East Asian and Middle Eastern Theatre**Moving beyond Europe, the narratives of women in acting become even more culturally specific, shaped by distinct artistic traditions, religious norms, and societal expectations. In Japan’s kabuki theatre, for instance, the Edo period’s ban on women led to the enduring convention of *onnagata*, male actors exquisitely portraying female roles. This practice, a complex art form in itself, continues to this day, showcasing a deep reverence for tradition that differs starkly from Western trajectories.

Chinese drama presents a varied tapestry: Beijing opera, like early Western theatre, traditionally saw men performing all roles, including female ones. However, in stark contrast, Shaoxing opera often features women playing *all* roles, including male characters, demonstrating an internal diversity within Asian theatrical traditions regarding gender representation on stage. These regional differences underscore how cultural values fundamentally dictate the structure of performance.

In the 19th-century Ottoman Empire, the advent of modern theatre in the 1850s, pioneered by an Armenian company, introduced new challenges. Muslim society, adhering to harem segregation, deemed acting unsuitable for women. Consequently, the first actresses were Christian Armenians, with Arousyak Papazian making her debut in 1857. Facing severe social stigma, these actresses often commanded higher salaries than their male counterparts, a curious inversion, reflecting the premium placed on women brave enough to defy norms and the scarcity of their talent. They uniquely continued their careers undisturbed even after the Armenian theatre monopoly ended, as no Muslim Turkish female actor appeared before Afife Jale in the 1920s.

A similar struggle unfolded in Egypt, where modern theatre began in 1870 under Yaqub Sanu. He found it nearly impossible to engage indigenous Egyptian Muslim women due to societal expectations of veiling and segregation. Forced to adapt, Sanu employed non-Muslim women, primarily poor Jewish girls like Milia Dayan and her sister, who became some of the first actresses in the Arab world alongside others like Miriam Samat. It wasn’t until Mounira El Mahdeya in 1915 that the first Muslim actress graced the stage in Egypt, marking a profound cultural shift that slowly, gradually, began to dismantle centuries of social strictures.

12. **The Modern Actor: Terminology, Compensation, and the Gender Pay Gap**In the contemporary acting world, even after millennia of evolution, debates persist, particularly concerning terminology, the harsh realities of compensation, and the undeniable gender pay gap. The term “actor,” while historically neutral, often gives way to “actress” for women, a distinction that has become increasingly contentious. The *OED* notes “actress” appearing in 1608, and in the 19th century, it was frequently linked to negative perceptions of women in the profession, often associating them with courtesans.

Today, there’s a strong push within the profession to reclaim the gender-neutral “actor” for all performers, a sentiment championed by figures like Whoopi Goldberg, who famously stated, “An actress can only play a woman. I’m an actor – I can play anything.” Organizations like *The Observer* and *The Guardian* have adopted style guides advocating for “actor” for both es, reserving “actress” primarily for award titles. However, the UK performers’ union Equity acknowledges the profession remains divided, reflecting a nuanced, ongoing discussion about language’s power and its implications for identity.

Beyond semantics, the financial landscape for actors remains a complex and often precarious one. While some in 17th-century England earned a comfortable living, and Shakespeare himself likely made a tradesman’s wage, the median hourly wage for actors in the United States in 2024 was a modest $23.33. This stark reality is further highlighted by the fact that only a fraction—12.7%—of SAG-AFTRA members earn enough to qualify for health plans, illustrating that for many, acting is a passion pursued with significant personal and financial sacrifice.

Despite these lower median incomes, the upper echelons of the profession reveal staggering wealth, with global film stars like Aamir Khan and Sandra Bullock earning tens of millions for single productions, showcasing the extreme disparity within the industry. Child actors, too, command substantial daily rates, though legal protections like California’s Coogan Act ensure a portion of their earnings is safeguarded for their adult lives, acknowledging their unique vulnerability.

However, a deeply ingrained issue continues to cast a long shadow: the pervasive gender pay gap. In 2015, *Forbes* reported that men on their list of top-paid actors made 2.5 times as much as top-paid actresses, meaning women earned just 40 cents for every dollar men made. This isn’t just a top-tier problem; it’s an industry-wide disparity, with white women earning 78 cents to every dollar a white man makes, and women of color facing even greater gaps. This enduring inequality highlights that while women have fought for, and won, their rightful place on stage and screen, the battle for equitable compensation and true parity is far from over.

The journey of the actor is a grand narrative of human expression, stretching from a lone Greek performer’s innovative monologue to the intricate, diverse, and often challenging world of contemporary media. It’s a story of societal shifts, artistic breakthroughs, and relentless individual resilience. From ancient prohibitions to modern stardom, the actor has constantly redefined their role, not just within the spotlight, but within the very fabric of human culture. This odyssey, marked by both profound triumphs and persistent struggles, reminds us that the stage, in all its forms, remains a powerful mirror, reflecting both our evolving ideals and the ongoing work towards a truly inclusive and equitable future for all who dare to dream in front of a camera or beneath the proscenium arch.