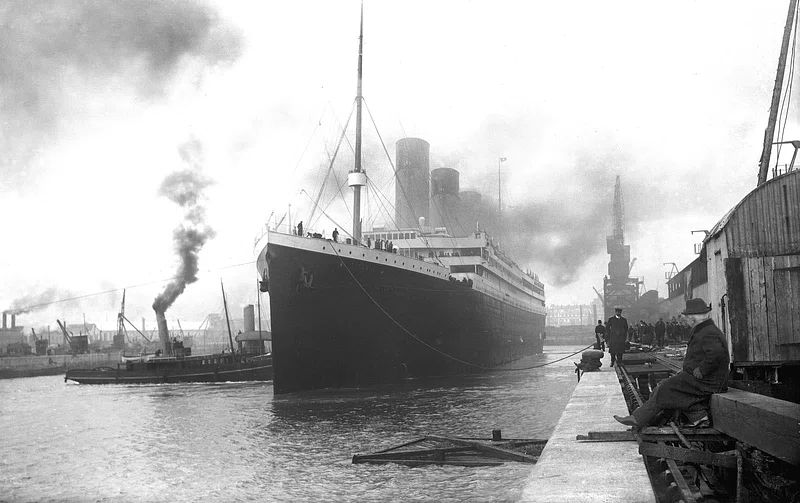

The RMS Titanic, a British ocean liner, stands as one of history’s most compelling narratives, a testament to early 20th-century engineering prowess and, tragically, a stark reminder of humanity’s hubris. Its maiden voyage in April 1912 from Southampton, England, to New York City, United States, culminated in an unforeseen disaster when it struck an iceberg, leading to its sinking in the early hours of April 15. The loss of approximately 1,500 lives out of an estimated 2,224 passengers and crew made this incident one of the deadliest peacetime sinkings of a single ship.

This magnificent vessel, operated by the White Star Line, was designed to be the pinnacle of luxury and safety, carrying some of the world’s wealthiest individuals alongside hundreds of emigrants seeking new lives in North America. Its story, however, transcends the immediate tragedy, drawing lasting public attention, inspiring significant changes in maritime safety regulations, and establishing an enduring legacy in popular culture. The Titanic’s narrative is a complex tapestry of ambition, innovation, and sorrow, continuing to captivate and inform us over a century later.

The genesis of the Olympic-class liners, which included the Titanic, began in mid-1907 with a pivotal discussion between J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the White Star Line, and American financier J. P. Morgan, who controlled the White Star Line’s parent corporation, the International Mercantile Marine Co. This period saw intense competition among major shipping lines, particularly from Cunard Line, which had recently launched the exceptionally fast Lusitania and Mauretania with Admiralty aid, and formidable German lines like Hamburg America and Norddeutscher Lloyd. Ismay, keenly aware of this rivalry, opted for a different strategy: to compete on sheer size and unparalleled luxury rather than speed.

His vision was to commission a new class of liners that would surpass anything previously conceived, embodying the very essence of comfort and opulence. These new ships were intended to be sufficiently swift to maintain a weekly transatlantic service with just three vessels, replacing older White Star Line stalwarts such as RMS Teutonic of 1889, RMS Majestic of 1890, and RMS Adriatic of 1907. This strategic decision laid the groundwork for the construction of ships that would redefine maritime travel.

The construction of these ambitious vessels was entrusted to Harland and Wolff, the Belfast shipbuilder with a long-established relationship with the White Star Line dating back to 1867. Harland and Wolff were given an extraordinary degree of creative freedom in designing these liners, operating under an unusual cost-plus-profit arrangement where expenditure was a relatively low priority. A cost of £3 million (approximately £370 million in 2023) was agreed for the first two ships, along with “extras to contract” and the standard five percent fee, underscoring the commitment to uncompromising quality.

The design team assembled by Harland and Wolff was truly exceptional, featuring luminaries such as Lord Pirrie, a director for both Harland and Wolff and White Star Line, and Thomas Andrews, the managing director of Harland and Wolff’s design department, who tragically perished with the ship. Edward Wilding, Andrews’s deputy, was responsible for calculating the ship’s design, stability, and trim, while Alexander Carlisle, the shipyard’s chief draughtsman and general manager, oversaw decorations, equipment, and general arrangements, including the implementation of an efficient lifeboat davit design. This collective expertise promised a vessel of unparalleled grandeur and sophistication.

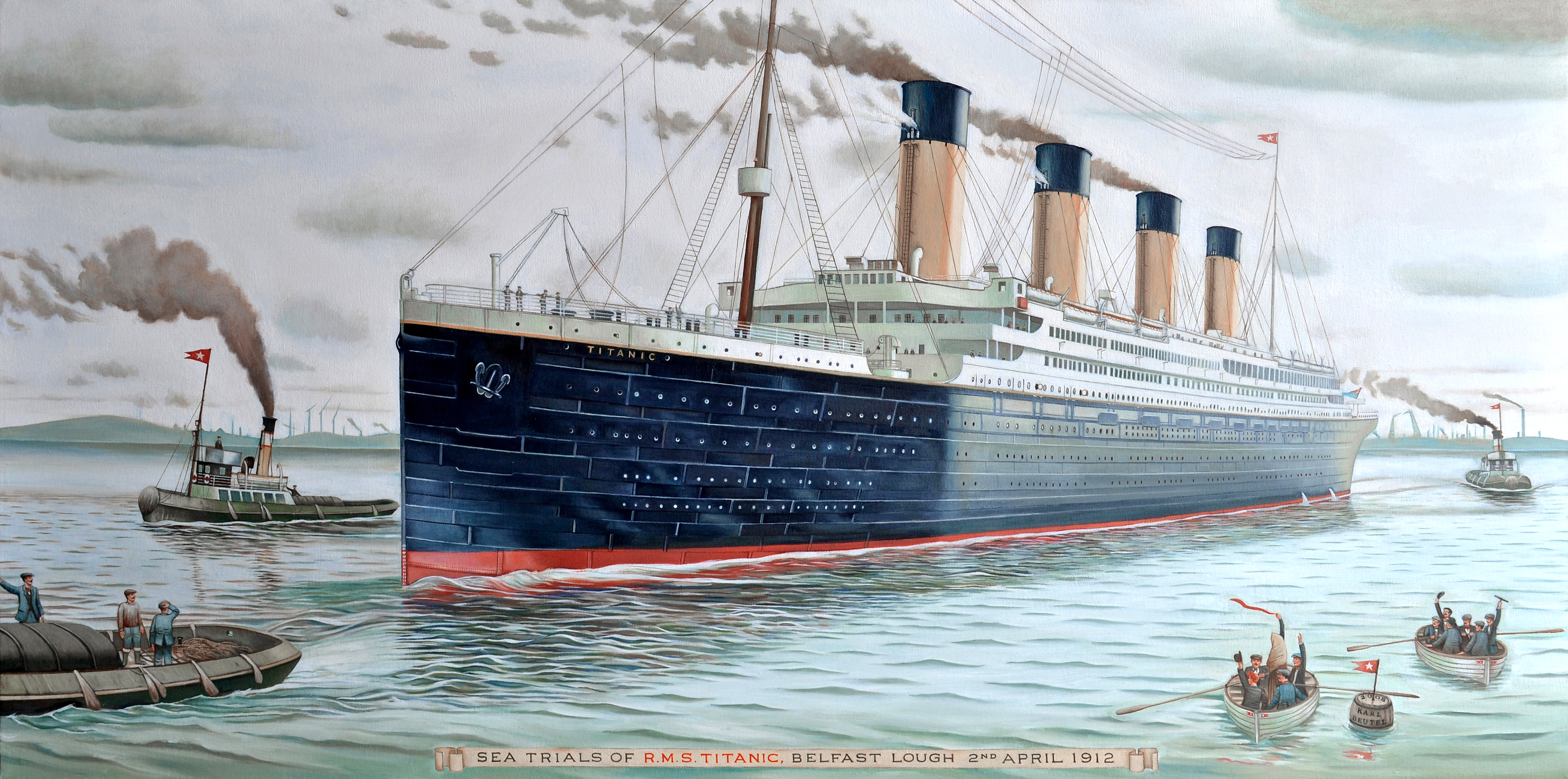

On July 29, 1908, the detailed drawings of the Olympic-class vessels were presented to J. Bruce Ismay and other White Star Line executives. Ismay promptly approved the design, signing three “letters of agreement” just two days later, officially authorizing the commencement of construction. The first ship, later named Olympic, was initially referred to simply as “Number 400,” marking it as Harland and Wolff’s 400th hull. Titanic, built upon a revised version of the same foundational design, was designated with the yard number 401, signaling its slightly refined characteristics.

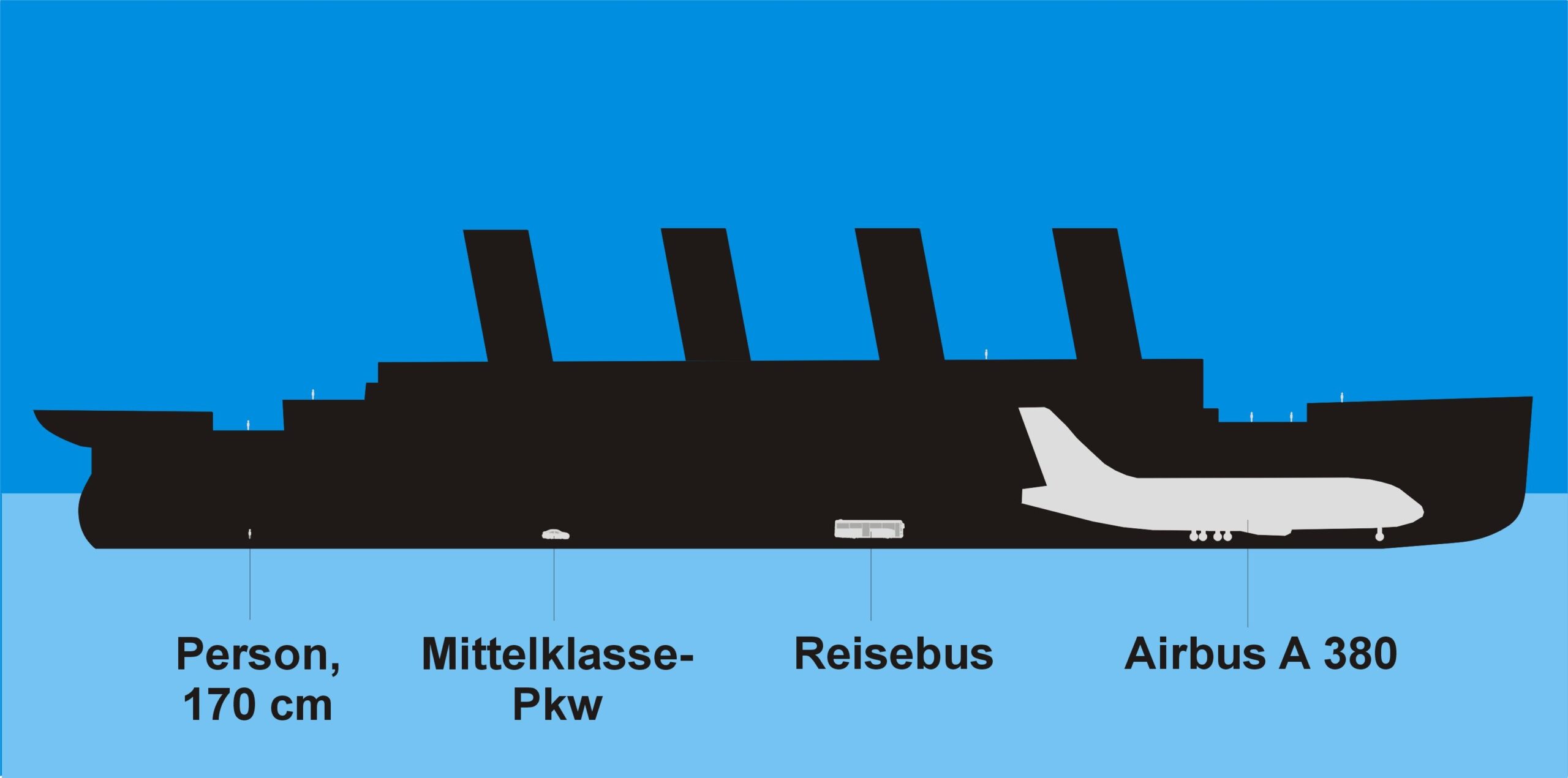

Upon its completion, the Titanic measured an impressive 882 feet 9 inches (269.06 meters) in length with a maximum breadth of 92 feet 6 inches (28.19 meters). Its total height, from the base of the keel to the top of the bridge, reached 104 feet (32 meters), a truly colossal scale for its era. The ship’s tonnage registered at 46,329 GRT and 21,831 NRT, with a draught of 34 feet 7 inches (10.54 meters) and displacing 52,310 tonnes.

The vessel boasted ten decks, excluding the very top of the officers’ quarters, with eight dedicated to passenger use, creating a veritable floating city. These decks, meticulously designed for both function and grandeur, ranged from the uppermost Boat Deck down to the lowest Orlop Deck and Tank Top. Each level presented a distinct environment tailored to the ship’s diverse population, from the most affluent passengers to the hardworking crew.

Venturing onto the Boat Deck, one encountered the primary location for the lifeboats, which were destined to be lowered into the North Atlantic during the fateful early hours of April 15, 1912. This deck also housed the bridge and wheelhouse at its forward end, positioned in front of the captain’s and officers’ quarters. The bridge itself stood 8 feet (2.4 meters) above the deck, extending outwards to facilitate ship control during docking maneuvers, with the wheelhouse nestled within its structure.

Midships on the Boat Deck, passengers found the stately entrance to the First Class Grand Staircase and the gymnasium, alongside the raised roof of the First Class lounge. Towards the rear, the roof of the First Class smoke room and the Second Class entrance were prominent features. Notably, just forward of the Second Class entrance, kennels were provided for the First Class passengers’ beloved dogs. This wood-covered deck was thoughtfully divided into four distinct promenades, segregated for officers, First Class passengers, engineers, and Second Class passengers, ensuring a structured yet spacious environment. Lifeboats lined the sides of the deck, with a deliberate gap in the First Class area to preserve unobstructed views, reflecting the ship’s emphasis on aesthetic appeal for its premier guests.

A Deck, famously known as the promenade deck, stretched an impressive 546 feet (166 meters) along the entire length of the superstructure. This deck was exclusively reserved for First Class passengers, offering them an expansive space for leisurely strolls and relaxation. It housed a variety of luxurious amenities, including First Class cabins, a refined reading and writing room, an elegant lounge, a comfortable smoke room, and the serene Palm Court. Every element on this deck was curated to provide an experience of unparalleled comfort and sophistication for elite travelers.

B Deck, also referred to as the bridge deck, served as the uppermost weight-bearing deck and the highest level of the hull itself. This deck featured even more First Class passenger accommodations, including six palatial staterooms, each boasting its own private promenade, providing an extraordinary degree of exclusivity and privacy. On the Titanic, this deck was home to the à la carte restaurant and the sophisticated Café Parisien, both offering exceptional luxury dining facilities for First Class passengers. These dining venues were managed by subcontracted chefs and their staff, all of whom, tragically, were lost in the disaster.

Additionally, B Deck contained the Second Class smoking room and its entrance hall, catering to the comforts of passengers in the next tier of accommodation. Forward of the bridge deck, the raised forecastle accommodated Number 1 hatch, the main access to the cargo holds, along with numerous pieces of machinery and the anchor housings. Aft of the bridge deck, the raised poop deck, spanning 106 feet (32 meters) long, served as a promenade for Third Class passengers. This area became a poignant site where many of the Titanic’s passengers and crew made their last stand as the ship succumbed to the icy waters. The forecastle and poop deck were distinctly separated from the bridge deck by well decks, maintaining structural and spatial divisions.

C Deck, known as the shelter deck, held the distinction of being the highest deck to run uninterrupted from stem to stern, providing continuous access across the ship. It encompassed both well decks, with the aft well deck serving as an integral part of the Third-Class promenade, highlighting White Star Line’s commitment to providing adequate open space even for its steerage passengers. Below the forecastle, crew cabins were efficiently housed, while Third-Class public rooms were situated beneath the poop deck. In the vast expanse between these areas, the majority of First Class cabins were located, alongside the Second-Class library, underscoring the ship’s careful spatial planning for its diverse passenger and crew populations.

D Deck, the saloon deck, was characterized by three prominent public rooms that formed the social heart of the ship for its upper-class passengers. These included the elegant First-Class reception room, the grand First-Class dining saloon, and the spacious Second-Class dining saloon. The galleys serving both first- and second-class passengers were also strategically located on this deck to ensure efficient service. An open space was thoughtfully provided for Third Class passengers, allowing them a designated area for gathering. This deck also featured cabins for First, Second, and Third-Class passengers, with berths specifically designated for firemen situated in the bow. Notably, D Deck represented the highest level reached by eight of the ship’s fifteen watertight bulkheads, a critical aspect of its much-touted safety design.

Moving down, E Deck, or the upper deck, was primarily dedicated to passenger accommodation for all three classes, offering a range of cabins to suit different budgets. In addition to passenger quarters, this deck also provided berths for essential crew members, including cooks, seamen, stewards, and trimmers. A long passageway, affectionately nicknamed ‘Scotland Road’ in a nod to a famous street in Liverpool, ran the length of E Deck. This passage served as a crucial thoroughfare, primarily utilized by Third Class passengers and crew members for movement throughout the ship.

F Deck, the middle deck, mainly accommodated Second- and Third-Class passengers, along with several departments of the crew, reflecting the ship’s hierarchical yet organized layout. A key feature on this deck was the Third Class dining saloon, providing a dedicated and improved dining experience for steerage passengers compared to many other vessels of the era. This deck also hosted a luxurious First Class bath complex, a marvel of opulence, which encompassed a deep saltwater swimming pool and an elaborate Victorian-style Turkish bath. The Turkish bath facility itself comprised a hot room, a warm (temperate) room, a cooling room, and two shampooing (massage) rooms, further complemented by a steam room and an electric bath, offering an unrivaled spa experience at sea.

Finally, G Deck, the lower deck, was notable for having the lowest portholes on the ship, positioned just above the waterline, offering a unique perspective of the ocean. This deck housed the First-Class squash court, providing an active recreational outlet for passengers. It also contained the travelling post office, a vital operational area where letters and parcels were diligently sorted, preparing them for delivery upon the ship’s arrival in port. Food provisions were also stored in considerable quantities on this deck. The structural integrity of G Deck was interrupted at several points by orlop (partial) decks, strategically placed over the boiler, engine, and turbine rooms to accommodate the ship’s immense machinery.

Beneath G Deck lay the orlop deck and the tank top, the lowest levels of the ship, situated below the waterline. The orlop decks served primarily as cargo spaces, demonstrating the ship’s dual function as both a passenger liner and a cargo carrier. The tank top, forming the inner bottom of the ship’s hull, provided the foundational platform for the Titanic’s massive boilers, engines, turbines, and electrical generators. This innermost area of the ship was strictly prohibited to passengers, ensuring the efficient and safe operation of the vessel’s powerful mechanical heart. Access to these lower levels from higher decks was facilitated by two flights of stairs within the fireman’s passage and twin spiral stairways near the bow, providing access up to D Deck, while ladders within the machinery spaces allowed internal access for the engineering crew.

The Titanic’s propulsion system was a marvel of contemporary marine engineering, designed for both power and efficiency. It featured three main engines: two reciprocating four-cylinder, triple-expansion steam engines and one centrally placed low-pressure Parsons turbine, each driving a dedicated propeller. The two reciprocating engines alone generated a combined output of 30,000 horsepower (22,000 kW), while the steam turbine contributed an additional 16,000 horsepower (12,000 kW). This innovative combination had been successfully employed by the White Star Line on an earlier liner, the Laurentic, proving its effectiveness.

This hybrid engine setup offered a superior balance of performance and speed. Reciprocating engines by themselves were insufficient to propel an Olympic-class liner at the desired speeds, while turbines, though powerful, were known to cause uncomfortable vibrations, a problem observed on Cunard’s all-turbine liners, Lusitania and Mauretania. By integrating reciprocating engines with a turbine, the Titanic achieved increased motive power while simultaneously reducing fuel consumption, using the same amount of steam. This ingenious design maximized both efficiency and passenger comfort, enhancing the journey for all aboard.

The sheer scale of these engines was breathtaking; each reciprocating engine measured an imposing 63 feet (19 meters) in length and weighed a staggering 720 tonnes, with their bedplates adding another 195 tonnes. These colossal powerplants were fed by steam generated in 29 boilers, a formidable array consisting of 24 double-ended and five single-ended units, collectively housing 159 furnaces. Each boiler was a massive structure, 15 feet 9 inches (4.80 meters) in diameter and 20 feet (6.1 meters) long, weighing 91.5 tonnes and capable of holding 48.5 tonnes of water, highlighting the immense energy required to propel such a vessel.

Fueling these furnaces was a ceaseless undertaking, requiring over 600 tonnes of coal to be hand-shoveled into them daily by a dedicated team of 176 firemen working around the clock. The Titanic’s bunkers could carry 6,611 tonnes of coal, with an additional 1,092 tonnes stored in Hold 3, demonstrating its substantial range. The arduous nature of this work, which involved constant shoveling in extreme heat, was relentless, dirty, and inherently dangerous. This strenuous labor, despite relatively good pay for the firemen, was associated with a high suicide rate among those in that demanding capacity, offering a grim insight into the human cost behind the ship’s power.

Exhaust steam from the reciprocating engines was channeled into the turbine, strategically positioned aft, further harnessing residual energy. From the turbine, the steam then passed into a surface condenser, a critical component designed to enhance the turbine’s efficiency and convert the steam back into water for reuse, closing the operational loop. The engines were directly connected to long shafts that drove the ship’s three propellers. The two outer, or wing, propellers were the largest, each featuring three blades crafted from manganese-bronze alloy, with a total diameter of 23.5 feet (7.2 meters). The central propeller, slightly smaller at 17 feet (5.2 meters) in diameter, could be stopped but notably not reversed, impacting the ship’s maneuverability.

The Titanic’s rudder was an immense component, measuring 78 feet 8 inches (23.98 meters) high and 15 feet 3 inches (4.65 meters) long, with a weight exceeding 100 tonnes. Its colossal size necessitated the use of powerful steering engines to maneuver it effectively. Two steam-powered steering engines were installed for this purpose, though typically only one was in operation at any given time, with the other held in reserve. These engines were connected to the short tiller via stiff springs, a clever design intended to isolate the steering engines from shocks caused by heavy seas or rapid changes in direction, thereby preventing damage. As a final emergency measure, the tiller could be manually moved by ropes connected to two steam capstans. These versatile capstans also served the crucial function of raising and lowering the ship’s five anchors, including one port, one starboard, one in the centerline, and two kedging anchors.

The ship’s internal systems were equally sophisticated, featuring a comprehensive waterworks capable of heating and pumping water to all corners of the vessel through an intricate network of pipes and valves. While the primary water supply was taken aboard when the Titanic was in port, the ship also possessed the crucial emergency capability to distil fresh water from seawater. However, this was not a straightforward process, as the distillation plant could quickly become clogged by salt deposits. A network of insulated ducts, equipped with electric fans, efficiently conveyed warm air throughout the ship, ensuring a comfortable environment. For added luxury and personalized comfort, First-Class cabins were fitted with supplementary electric heaters, and the “Sirocco Fan,” a centrifugal fan resulting from a deal between Harland and Wolff and Davidson and Co., Sirocco Works, played a role in the ship’s ventilation system.

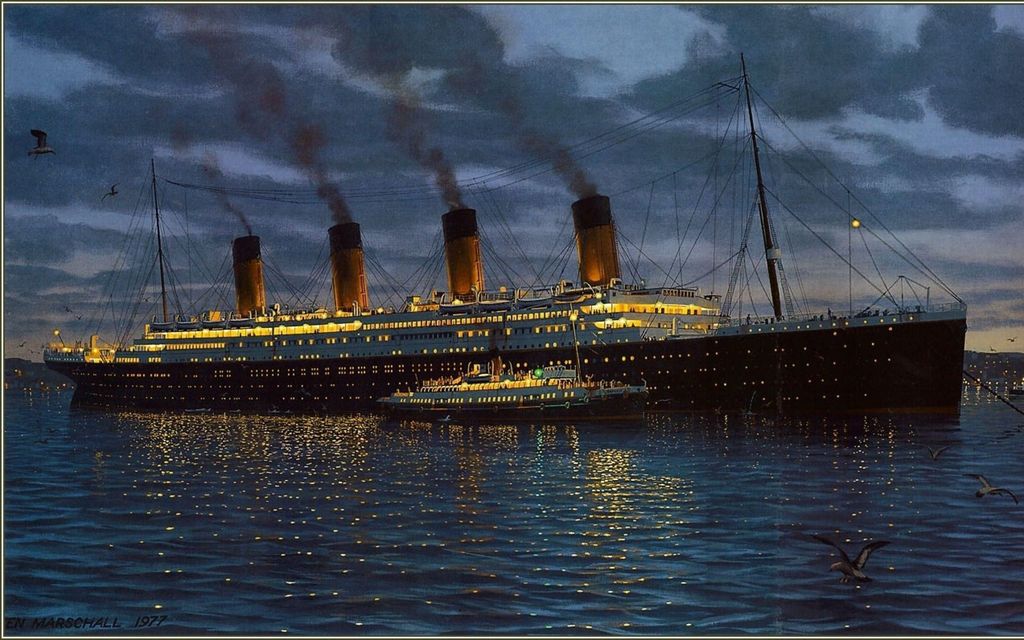

Central to the Titanic’s operational capabilities and passenger services was its radiotelegraph equipment, then known as wireless telegraphy, leased from the Marconi International Marine Communication Company. The Marconi company also supplied two of its skilled employees, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, to serve as the ship’s dedicated operators. This vital service maintained a continuous 24-hour schedule, primarily focused on sending and receiving passenger telegrams, affectionately termed “marconigrams,” but also handling critical navigation messages, including essential weather reports and ice warnings. The radio room, a nerve center of communication, was strategically located on the Boat Deck, within the officers’ quarters.

First-class common rooms were designed to be breathtaking in their scope and lavishly decorated, creating an atmosphere of unparalleled grandeur. These included a lounge reminiscent of the magnificent Palace of Versailles, an enormous reception room perfect for social gatherings, a refined men’s smoking room, and a quiet reading and writing room. For an unparalleled culinary experience, an à la carte restaurant, styled after the esteemed Ritz Hotel, operated as a concession managed by the famous Italian restaurateur Gaspare Gatti. Adding to this gastronomic luxury was the charming Café Parisien, decorated in the style of a French pavement café, complete with ivy-covered trellises and wicker furniture, serving as an intimate annex to the main restaurant. Here, at an extra cost, first-class passengers could savor the finest French haute cuisine in the most luxurious surroundings imaginable. Additionally, the Verandah Café offered tea and light refreshments, providing grand views of the ocean, truly embodying the essence of leisurely travel. The dining saloon on D Deck, designed by Charles Fitzroy Doll, was a monumental space, measuring 114 feet (35 meters) long by 92 feet (28 meters) wide, making it the largest room afloat and capable of seating almost 600 passengers simultaneously.

One of the Titanic’s most iconic and distinctive features was its First Class staircase, universally known as the Grand Staircase or Grand Stairway. Crafted from solid English oak with a sweeping, elegant curve, this architectural masterpiece descended through seven decks of the ship, from the Boat Deck down to E Deck, before culminating in a simplified single flight on F Deck. It was crowned with a magnificent dome of wrought iron and glass, allowing natural light to flood the stairwell, illuminating its grandeur. Each landing off the staircase provided access to ornate entrance halls, exquisitely paneled in the William & Mary style and lit by glistening ormolu and crystal light fixtures, creating an atmosphere of unparalleled opulence.

At the uppermost landing, a large, intricately carved wooden panel captivated observers, featuring a clock flanked by figures of “Honour and Glory Crowning Time,” a symbolic representation of the ship’s enduring ambition. Tragically, the Grand Staircase was destroyed during the sinking, leaving behind only a void in the ship, which modern explorers now utilize to access the lower decks of the wreck. During the filming of James Cameron’s 1997 movie ‘Titanic’, his replica of the Grand Staircase was dramatically ripped from its foundations by the force of inrushing water on the set, mirroring some theories that, during the actual disaster, the entire Grand Staircase was ejected upwards through the dome by the immense pressure of the sinking.

While primarily a passenger liner, the Titanic also carried a substantial amount of cargo, fulfilling its designation as a Royal Mail Ship (RMS) by transporting mail under contract with both the Royal Mail and the United States Post Office Department. For the efficient storage of letters, parcels, and specie (bullion, coins, and other valuables), a significant 26,800 cubic feet (760 m3) of space was allocated. The dedicated Sea Post Office on G Deck was a bustling hub, manned by five postal clerks—three Americans and two Britons—who worked tirelessly for 13 hours a day, seven days a week, meticulously sorting up to 60,000 items daily.

Beyond official mail, the ship’s passengers brought with them an enormous amount of personal baggage, occupying another 19,455 cubic feet (550.9 m3) specifically for first- and second-class belongings. In addition to these personal effects, a considerable quantity of regular cargo was onboard, ranging from various furniture pieces to diverse foodstuffs, and even including a 1912 Renault Type CE Coupe de Ville motor car. Despite later myths that emerged about the cargo, the manifest for Titanic’s maiden voyage was, in reality, quite mundane, containing no gold, exotic minerals, or diamonds. One of the more famous items lost in the shipwreck, a jewelled copy of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, was valued at a comparatively modest £405 (£50,600 in 2023).

However, according to the claims for compensation filed with Commissioner Gilchrist following the Senate Inquiry, the single most highly valued item of luggage or cargo was a magnificent neoclassical oil painting titled “La Circassienne au Bain” by the French artist Merry-Joseph Blondel. Its owner, first-class passenger Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson, filed a substantial claim for $100,000 (equivalent to $2,300,000 in 2023) in compensation for the artwork’s loss, underscoring its significant artistic and monetary value. Other intriguing items listed in the manifest included 12 cases of ostrich feathers, 76 cases of “Dragon’s Blood,” and 16 cases of calabashes, providing a fascinating glimpse into the diverse goods transported on the ill-fated voyage. For the efficient loading and unloading of this cargo and baggage, the Titanic was equipped with eight electric cranes, four electric winches, and three steam winches, demonstrating its robust operational capabilities. It is estimated that the ship utilized approximately 415 tonnes of coal while still in Southampton, solely for generating steam to power the cargo winches and provide essential heat and light throughout the vessel.

The lifeboat situation on the Titanic remains one of the most poignant and debated aspects of its history. Like its sister ship, Olympic, the Titanic carried a total of 20 lifeboats: 14 standard wooden Harland and Wolff lifeboats, each designed to hold 65 people, and four Engelhardt “collapsible” lifeboats (identified as A to D), which featured wooden bottoms and collapsible canvas sides, each with a capacity for 47 people. Additionally, the ship was equipped with two emergency cutters, each capable of accommodating 40 people. This combined fleet of lifeboats was intended to accommodate 1,178 individuals.

All lifeboats were securely stowed on the Boat Deck. With the exception of collapsible lifeboats A and B, they were connected to davits by ropes, ready for deployment. Those on the starboard side were oddly numbered 1–15 from bow to stern, while those on the port side were even-numbered 2–16 from bow to stern. Both cutters were kept swung out, suspended from their davits, ensuring readiness for immediate use. Collapsible lifeboats C and D were stowed on the Boat Deck, immediately inboard of boats 1 and 2, respectively, also connected to davits. However, collapsible boats A and B posed a unique challenge as they were stored on the roof of the officers’ quarters, on either side of the number 1 funnel, without dedicated davits, making their manual launch exceptionally difficult. Each lifeboat was stocked with essential provisions, including food, water, blankets, and a spare life belt, and lifeline ropes adorned their sides, intended to facilitate the rescue of additional individuals from the water if necessary.

Despite the tragic outcome, it is crucial to note that the Titanic’s lifeboat provision actually exceeded the legal requirements of the era. The ship was equipped with 16 sets of davits, each capable of handling three lifeboats, a design choice by Alexander Carlisle that theoretically would have allowed the Titanic to carry up to 48 wooden lifeboats. However, the White Star Line ultimately decided to carry only 16 wooden lifeboats and four collapsibles, sufficient for 1,178 people, which represented only one-third of the Titanic’s total passenger and crew capacity. At the time, the British Board of Trade’s regulations mandated that British vessels over 10,000 tonnes carry only 16 lifeboats with a capacity for 990 occupants. Thus, the White Star Line provided six more lifeboats than legally required, allowing room for an additional 338 people, an effort to surpass the minimum safety standards.

A critical point of understanding from the era is that lifeboats were not intended to accommodate the entire population of a sinking ship and power them to shore. Instead, they were designed to ferry survivors from the distressed vessel to a rescuing ship. This operational philosophy underpinned the regulations of the time. Indeed, had the SS Californian, a ship in the vicinity, responded to the Titanic’s distress calls, it is conceivable that the lifeboats might have successfully ferried all passengers to safety as originally planned within the maritime paradigm of the period. Tragically, when the ship sank, many of the lifeboats that were successfully lowered were only filled to an average of 60% capacity, underscoring the chaos and lack of coordinated action during the final hours.

The legacy of the Titanic is not merely in its opulent amenities or its vast dimensions, but in the enduring lessons it imparted to the world. It serves as a permanent reminder that even the grandest creations, those deemed “unsinkable,” remain subject to the elements and the fallibility of human planning. Its sunken hull, now a silent monument beneath the icy waves, continues to draw the gaze of humanity, compelling us to reflect on past events and guiding the evolution of maritime safety to this day. The Titanic, in its very absence, speaks volumes, ensuring its place in history is not simply remembered, but perpetually learned from.